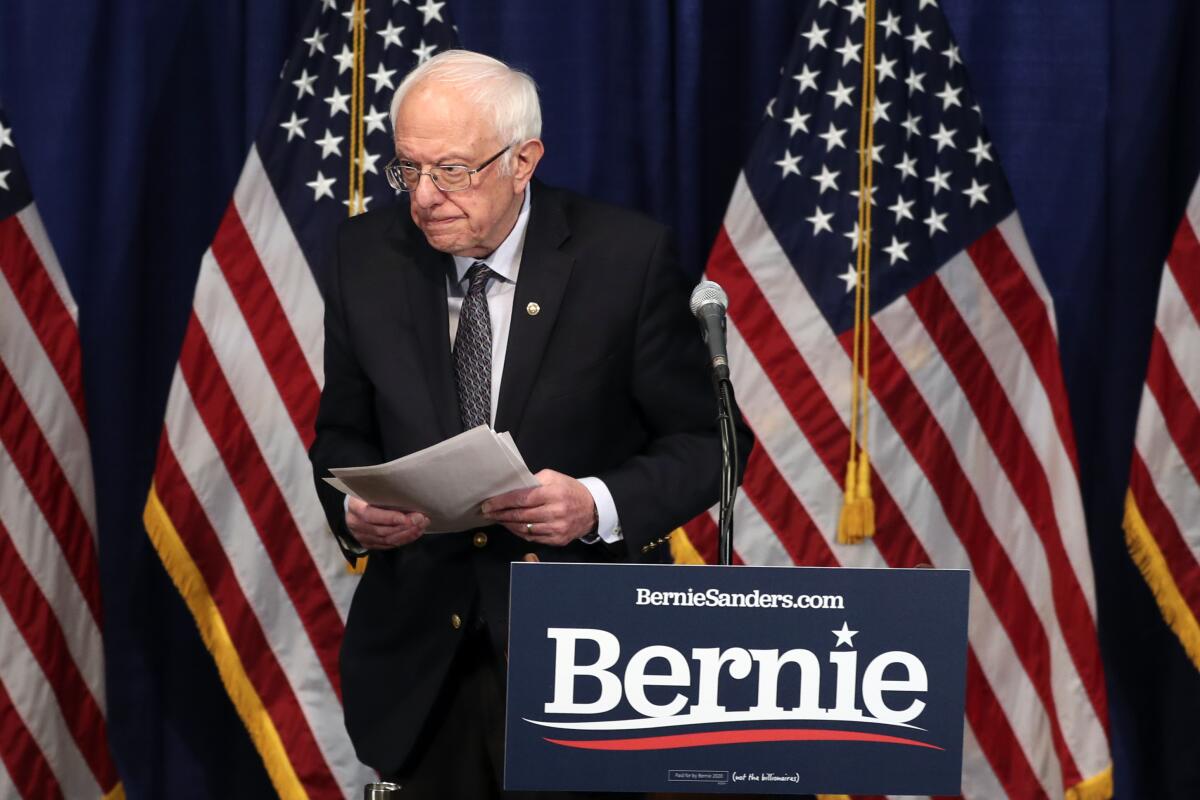

Bernie Sanders says he’ll continue campaign, but opens a path toward an exit

WASHINGTON — Sen. Bernie Sanders announced Wednesday that he is staying in the 2020 presidential race, but gone is the swagger of an insurgent candidate who for months defiantly projected that the nomination was within his grasp.

Chastened by multiple defeats over the last two weeks, several in states that he won in primaries four years ago, Sanders acknowledged at a news conference Wednesday that the potential path he once had to the nomination is rapidly closing as voters he expected to be in his coalition have grown doubtful over his ability to beat President Trump and are aligning with former Vice President Joe Biden.

“While our campaign has won the ideological debate, we are losing the debate over electability,” he said.

Speaking to reporters in his home state of Vermont, Sanders signaled a new role for himself in the race: using the energy and momentum of his grass-roots movement to push Biden into embracing a more progressive platform.

He rattled off a litany of policy challenges he plans to confront Biden with during the next presidential debate in Arizona on Sunday, offering a road map of sorts to concessions that he hopes to gain. But he expressed regret that so many change-hungry Americans — mistakenly, Sanders argued — see Biden as a safer bet for Democrats in November.

“Donald Trump must be defeated, and I will do everything in my power to make that happen,” Sanders said during a 10-minute statement, after which he took no questions. “On Sunday night, in the first one-on-one debate of this campaign, the American people will have the opportunity to see which candidate is best positioned to accomplish that goal.”

His aides and allies had been saying he should not drop out, despite Biden’s growing lead in convention delegates and a primary calendar that is moving into states even more unfriendly to Sanders in the coming weeks.

Sanders focused squarely and soberly on his policy differences with Biden — “Medicare for all,” climate change, immigration and more — and said he’d press Biden in the debate: “Joe, what are you going to do?”

Addressing those issues, he said, would allow Democrats to beat Trump by appealing to the younger voters who have flocked to Sanders in droves.

“Today I say to the Democratic establishment, in order to win in the future, you need to win the voters who represent the future of our country,” he said. “And you must speak to the issues of concern to them. You cannot simply be satisfied by winning the votes of older people. “

The tone was a remarkable shift for Sanders, scarcely resembling the candidate who remained defiant to the last in his 2016 race against Hillary Clinton.

Gone was the vow that “we are in till the last ballot is cast,” as he declared four years ago. He did not accuse Democratic officials of rigging the primary against him, as he did then. He did not rail against a corrupt party establishment, as he did then and has at some points earlier in the current campaign.

The more conciliatory approach reflects the very different circumstances of 2020. In the short stretch since voting began a month ago, Sanders has plummeted from the race’s front-runner — a position he never held in 2016 — to severe underdog. His prospects for recovery in this race are much bleaker than they were at this point in his last run, a reflection of the primary calendar as well as the extent to which the party has coalesced around Biden.

Democrats are exhausted from three years of Trump and horrified by the prospect he could win another term. Facing that, Sanders appears unwilling to inflict the kind of damage on the front-runner that he did in 2016.

He and Biden also do not display the kind of personal animosity he and Clinton did. Biden and Sanders have long had a cordial relationship, and the former vice president was complimentary of Sanders throughout the Vermonter’s last presidential bid.

“I am not a populist. But Bernie Sanders, he’s doing a helluva job,” Biden remarked at one point in 2015.

Some Biden supporters were, nonetheless, blunt in their calls for Sanders to quit after Tuesday’s election results.

“I think it is time for us to shut this primary down. It is time for us to cancel the rest of these debates,” Rep. James E. Clyburn, an influential South Carolina Democrat, said Tuesday night on NPR.

Others were more patient. Marlon Kimpson, a South Carolina state senator who backed Biden, said Sanders should not be pressured.

“He has earned enough votes and represents a significant number of people and deserves to stay in until he sees fit to withdraw from the race,” Kimpson said Wednesday.

“It is very important that we have a big tent to include the progressives,”

And Sanders’ supporters argued that continuing competition would strengthen Biden’s candidacy.

“Primaries should be explicit contrasts — and tough primaries don’t weaken general election nominees, they strengthen them,” David Sirota, a Sanders advisor, said on Twitter. “Establishment demands for silence in the name of unity — or for the end of a contested primary — don’t serve the cause of defeating Trump. They weaken that cause.”

Biden himself, in a speech to supporters in Philadelphia on Tuesday night as his victories unfolded, was measured. He was careful to say he was not taking the nomination for granted and offered an olive branch to Sanders supporters, emphasizing their “common goal” of beating Trump.

Biden still has a long way to go for the 1,991 pledged delegates he needs to win the nomination, and 26 states plus the District of Columbia and some U.S. territories remain to hold primaries. But barring unforeseen and dramatic developments, he is on track to quickly establish an insurmountable lead.

According to the delegate count maintained by the Associated Press, Biden had accrued 864 delegates to Sanders’ 710. That means Biden needs to win just half the remaining delegates to lock down the nomination; Sanders would need about 57%.

That task for Sanders is even harder than it might seem, since Biden is almost sure to win heavy victories in some of the big states voting later this month. All four of the states to vote next Tuesday — Florida, Ohio, Illinois and Arizona — are places where Sanders lost to Clinton in 2016. They offer gigantic caches of delegates, and polls show all of them favoring Biden.

If the contest continues into next week, Florida will loom especially large. The state has 219 delegates at stake, and Democrats hope to flip it back to their column in the general election. President Obama carried the state in both of his elections, but Trump won it in 2016.

Recent Florida polls show Biden crushing Sanders with support from more than 60% of likely primary voters.

Biden has a demographic advantage there because he does well among voters older than 45 and black voters, who made up 64% and 28%, respectively, of the state’s primary electorate in 2016, according to exit polls. While Sanders has done well among Latino voters in other states, Sanders’ recent defense of the accomplishments of Fidel Castro’s government inflamed Florida’s strongly anti-Castro Cuban American population.

Even with Sanders still in the race, Biden is beginning to focus more on how to unify the party and begin to prosecute the case against Trump in the fall. Some of that effort may go into finding a running mate to bridge party divides, but that choice is probably months away.

Jane Kleeb, chairman of the Nebraska Democratic Party, said Biden will have to offer more than olive-branch words to Sanders and his allies, and embrace a more progressive platform on issues like climate change.

“When we talk about unity, I think that usually means shut up and get on board,” said Kleeb, who has been neutral in the primary but is on the board of Our Revolution, a political group aligned with Sanders. “If we are truly going to unify the party — where all shades of blue are welcome — you make space for bright progressive turquoise and moderate navy blue.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.