Coronavirus is changing political campaigning as we know it

Like almost everywhere else, news of the coronavirus spread horribly fast in Louisiana.

The state’s first presumptive case was announced Monday; it was followed by dozens more. Within two days, the governor had declared a state of emergency. Within four days, schools were closed and public gatherings banned.

By Friday, presented with the choice of holding a presidential primary on April 4 that could theoretically kill people if voters infected others at polling sites, Louisiana did something radical: It delayed the election until June, which is allowed under state emergency law.

“We spent most of yesterday working as a team, looking for ways to try to carry out the election, and we kept running into barrier after barrier,” Secretary of State R. Kyle Ardoin said at a news conference, adding that more than half of the state’s polling place administrators were 65 or older — the highest-risk group for being killed by COVID-19.

In the U.S. and around the world, the coronavirus outbreak has begun constricting the traditional pomp and practice of democracy, halting candidates’ and organizers’ ability to campaign and get their message out, while threatening voters’ ability to get to the polls and safely exercise their rights.

Local and mayoral elections in England have been postponed for a year as COVID-19 cases skyrocket; Israelis under quarantine had to vote at special drive-through polling sites, leading to complaints of long lines and confusing instructions.

The Wyoming Democratic Party canceled its own in-person caucuses on April 4 in favor of mail balloting, and joined party leaders in Iowa and Nevada in postponing the county conventions where delegates are chosen to represent the state’s voters at the Democratic National Convention.

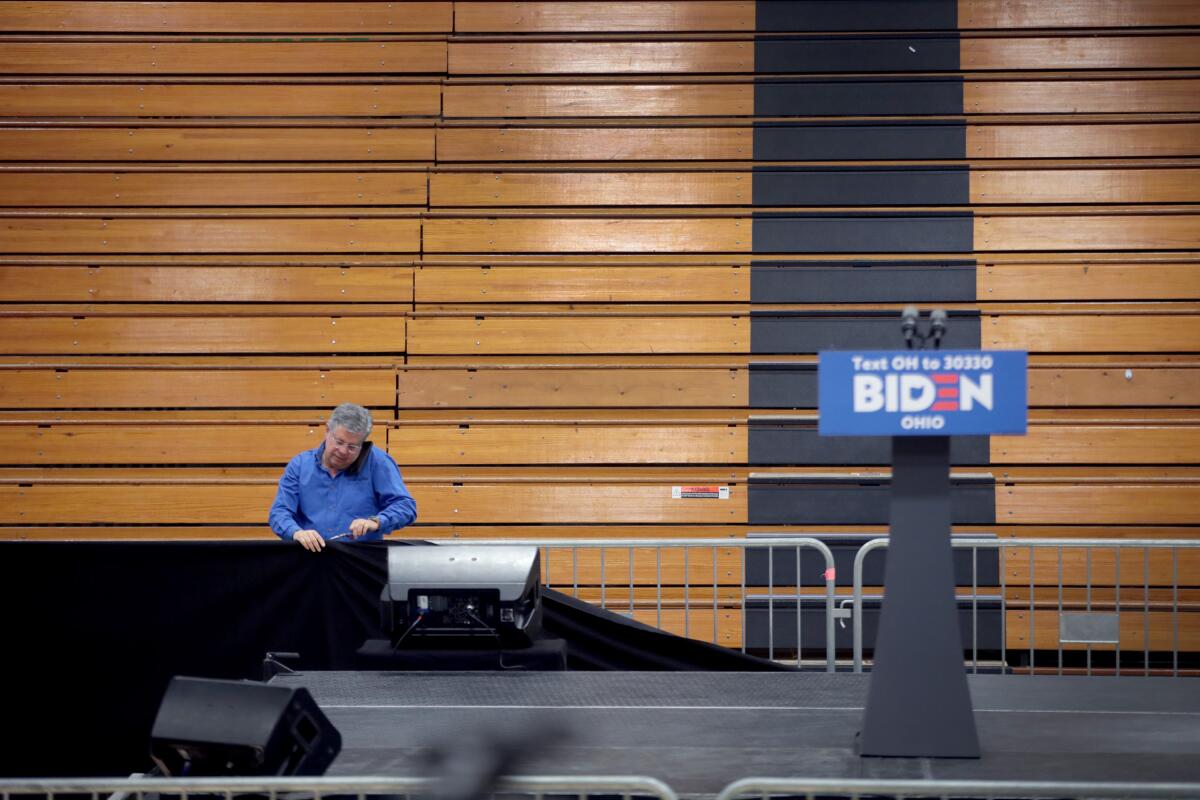

The coronavirus outbreak has shoved the presidential race off the campaign trail, forcing the cancellation of rallies in a manner not seen since the Spanish Flu pandemic interrupted the midterm campaigns of 1918.

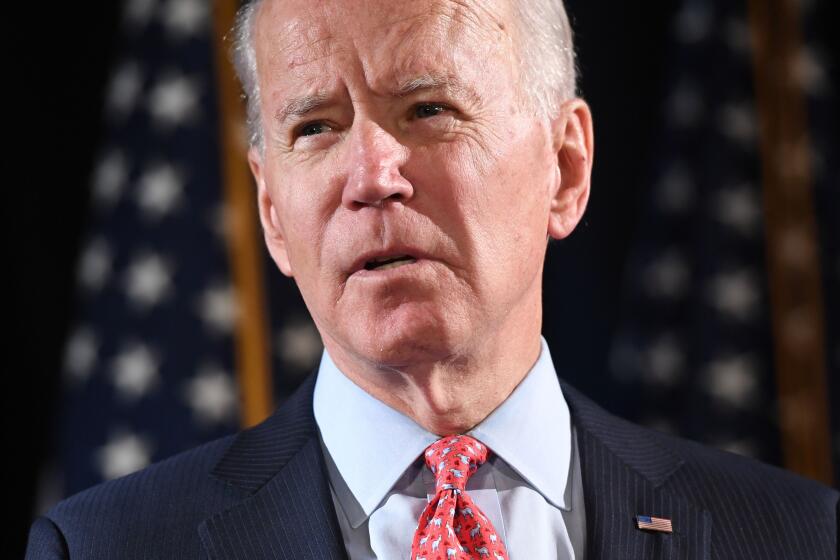

Democratic former Vice President Joe Biden, 77, and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, 78 — whose advanced ages make COVID-19 particularly hazardous for their own safety — have effectively stopped holding in-person events, instead relying on broadcast speeches and “virtual” town halls.

Biden and Sanders’ campaign staffers have been ordered to work from home, and field organizing has shifted to phone banking and texting, and other digital spaces that the virus can’t reach.

President Trump, 73, who tried for weeks to downplay the threat, had hinted at holding future rallies — the bread and butter of his 2016 run and a continuing staple of his presidency — but has gradually given in to the guidance of public health officials.

Biden’s speech on coronavirus dovetails with Democrats’ strategy of portraying Trump as a feckless and ineffective leader.

After announcing a “Catholics For Trump” event in Wisconsin for next week, the president’s campaign said days later that the gathering would be postponed. The White House, which earlier this week insisted Trump would travel to Nevada and Colorado this weekend for political events, also reversed course and canceled the trip. A campaign fundraiser scheduled for this weekend in Florida was also scrapped, and the Trump campaign has urged all staffers to work from home Friday through Monday as its Rosslyn, Va., offices are cleaned.

Sanders confessed on Friday that he would prefer to be campaigning in upcoming primary states like Florida and Ohio rather than talking to a small group of reporters at a news conference in Burlington, Vt., but he acknowledged that the virus had taken a hand.

“I don’t think there’s anybody out there, no matter what your political views may be, that wants to see people infected because they are voting,” Sanders said.

Sanders has frequently said that his campaign is all about “bringing people together,” both metaphorically and physically, often through mass rallies now discouraged by health officials as overly dangerous vectors for potential infection. Sanders sounded wistful as he described a campaign that could no longer exist.

“We do more rallies than anybody else; they’re often well attended. I love to do them. We have done dozens of town meetings, which I love also, because you can hear directly from people,” Sanders said. “And that is changing.”

“The health and safety of the public is our number one priority,” the Biden campaign said Wednesday.

A “virtual” town hall Biden held with Illinois voters on Friday afternoon had “some technical difficulties,” as Biden put it apologetically, including garbled audio in the beginning.

At the start of the event, Biden invited former Surgeon General Vivek Murthy to outline steps voters can take at the polls to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

At one point he apologized for the format to a voter preparing to ask a question. “It’s difficult,” Biden said at what was scheduled as a two-hour event. The town hall ended abruptly after about 15 minutes of questions.

By declaring a national emergency, a move he had resisted, President Trump frees up money to help states respond to the coronavirus pandemic.

Top election officials in Florida, Arizona, Illinois and Ohio insisted on Friday that in-person voting was still safe and that their Tuesday contests would be held as scheduled.

“Americans have participated in elections during challenging times in the past, and based on the best information we have from public health officials, we are confident that voters in our states can safely and securely cast their ballots in their election, and that otherwise healthy poll workers can and should carry out their patriotic duties on Tuesday,” the four states’ secretaries of state said in an unusual joint statement.

Biden deputy campaign manager Kate Bedingfield echoed those assurances. “Voting is at the very heart of who we are as a democracy,” she said in a statement. “As election officials working with public health officials are demonstrating throughout the country, our elections can be conducted safely in consultation with public health officials.”

Officials in states hosting elections on Tuesday have instructed poll workers to wipe down machines to limit the spread of germs. And some counties have moved polling locations away from vulnerable communities.

Maricopa County in Arizona, the second-largest district in the country after Los Angeles County, relocated polling locations out of senior living facilities after conferring with local health experts, said Megan Gilbertson, communications director for the county’s elections department.

Confusion swirled in the county Friday as Recorder Adrian Fontes announced that he would try to mail ballots to all voters who had not voted early, adding that officials had been unable to obtain enough cleaning supplies to keep voting sites safe. But Arizona’s secretary of state questioned whether such a move was legal, according to the Arizona Republic.

In Leon County, Fla., poll workers will remind voters to stand slightly apart, and each location will have hand sanitizer available.

“Our contingency plans have contingency plans,” said Leon County Supervisor of Elections Mark Earley, who witnessed the 2000 presidential recount as well as polling at locations with roofs ripped off by Hurricane Charlie in 2004. “We always try and stay ready.”

Still, campaigns and grass-roots organizers are scrambling to figure out how to adjust their on-the-ground operations to reach voters, who may be focused on dealing with everyday challenges presented by the pandemic.

Nabilah Islam, a Democrat who is running for Congress in Georgia’s 7th District northeast of Atlanta, made the decision Thursday to cancel in-person canvassing for her volunteers and staff.

She said she is among those who do not have health insurance, and is worried about getting sick. “It was a tough decision to make, but your health is your wealth, and so I want to make sure they’re protected,” she said.

But wealth is wealth, too: With about 70 days to go until she faces off against five other Democrats, Islam said she’s trying to figure out a way to campaign and fundraise virtually. She said she had met most of her small-dollar donors at meet-and-greet events, but those have been canceled, as have candidate forums.

“At the end of the day, you can’t replace face-to-face contact,” Islam said. “Phone banking and text banking is supplemental, but knocking on doors is the best way to talk to voters about your campaign and earn their vote.”

Advocacy groups that do similar door-to-door and other in-person campaign work face similar safety challenges.

“I have a lot of field operations all across the nation, and I need to decide when to pull the trigger” on pulling staff off the streets, said Hector Sanchez Barba, CEO and executive director of Mi Familia Vota, a Latino advocacy group. “This could have a drastic impact on our operations, and obviously we want to get as much done as possible before we close shop.”

For communities that have often felt ignored by political candidates, “face-to-face interaction is so critical [to] the establishment of trust,” Sanchez Barba said. Just as important, the virus has arrived when “there’s so much on the line” in the presidential election, he added.

“It’s a top priority to make sure we have better leadership and we remove hate and violence from the White House,” Sanchez Barba said. “So the question is, how is this coronavirus affecting our democracy?”

Times staff writer Eli Stokols contributed to this report from Washington.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.