Essential Politics: Biden promised bipartisanship. Now he’s redefining it

WASHINGTON — This is the April 16, 2021, edition of the Essential Politics newsletter. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox three times a week.

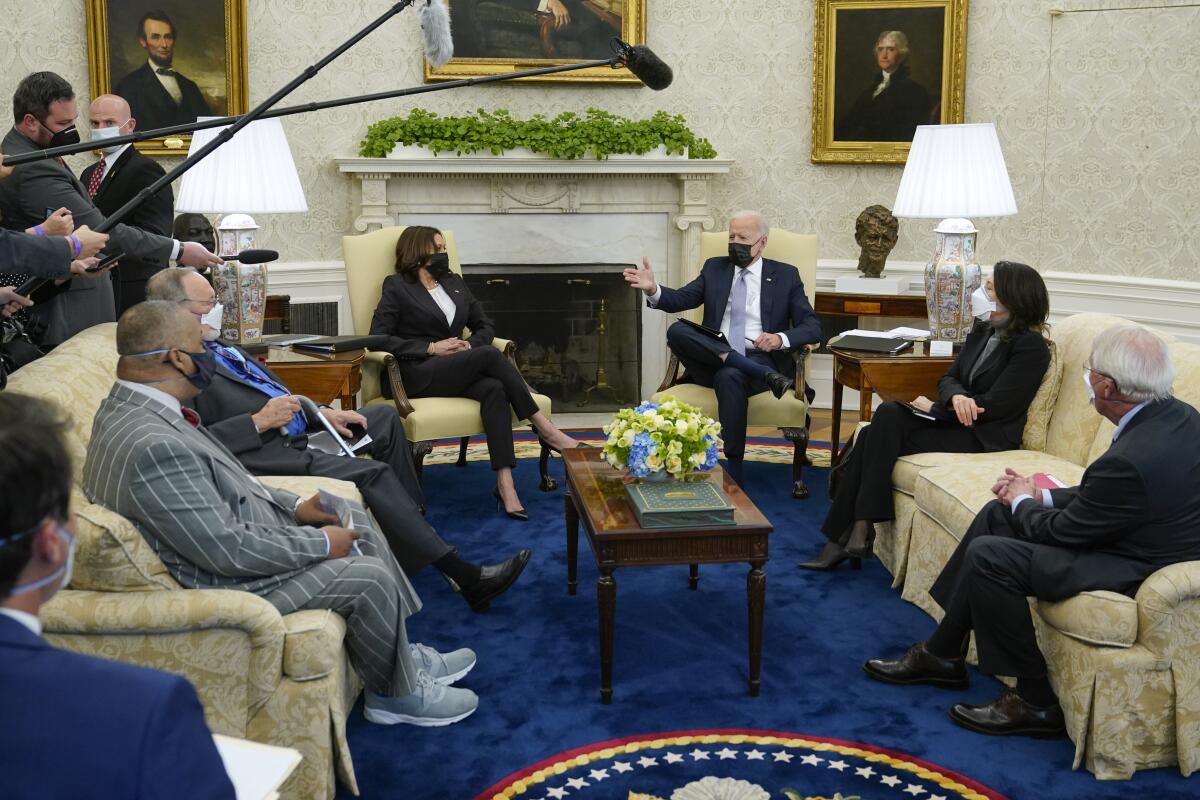

When then-candidate Joe Biden promised to restore bipartisanship to the nation’s political debates, polls showed most voters didn’t believe it would happen.

Since Biden took office, that voter skepticism has proved wise: Biden’s $1.9-trillion COVID-19 relief package passed without any GOP support, and there’s a good chance that his ambitious agenda for building up the nation’s infrastructure and aiding its families — and the taxes to pay for it — will follow the same path.

The less conservative Republicans in the Senate — lawmakers such as Sens. Susan Collins of Maine, Mitt Romney of Utah and Rob Portman of Ohio — had high hopes of being Biden’s deal-making partners. Instead, they’ve mostly found themselves on the outside as Biden works to maintain unity within his Democratic coalition, which spans an ideological range from Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York to Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Rather than drop the bipartisanship theme, however, Biden and his aides have tried to redefine it, claiming that their proposals have support from both parties’ voters, even if not from elected officials.

That’s not quite true, either. But Biden, nonetheless, has managed at least one significant bipartisan achievement.

A different age

Biden grew up politically in an environment very different than today’s. The 1972 election, in which he first won a seat in the Senate, was by one measure the least partisan in recent American history: President Nixon won reelection in a landslide, but 190 Democrats won seats in the House in districts he carried. Today, such split-ticket elections are vanishingly rare.

The Senate that Biden joined had conservatives and liberals from both parties, including liberal Republicans Charles Mathias of Maryland, Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, Jacob Javits of New York and Mark Hatfield of Oregon. They often went by the label Rockefeller Republicans, and the man many of them had supported for president, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller of New York, served as vice president and presiding officer of the Senate for much of Biden’s first term.

In that political system, major legislation almost always required a coalition across party lines. With voters willing to split their tickets, lawmakers faced no significant penalty for working with members of the other party.

By Biden’s second term, with the election of President Reagan and the ascendancy of the GOP’s conservative wing, that political system was already disappearing.

Even as the two parties grew more distinct ideologically, however, a lot of elected officials of Biden’s generation viewed the bipartisan cooperation of the 1970s as the norm and the greater partisanship of the present as an aberration.

That’s part of the background for understanding remarks from Biden like this from a campaign speech a few weeks before November’s election:

“We need to revive the spirit of bipartisanship in this country,” he said. “When I say that, and I said that from the time I announced, I was told that, ‘Maybe that’s the way things used to work, Joe, you got a lot done before, Joe, but you can’t do that anymore.’ Well, I’m here to tell you and say we can, and we must.”

He hasn’t. At least not so far.

In comments to reporters earlier this month, Biden put the onus on Republicans — at least on the COVID-19 package.

“They started off at $600 billion, and that was it,” he said, referring to the negotiations he had with Collins and other Senate Republicans over their counterproposals. He might have agreed to a plan in the range of $1.2 trillion or $1.3 trillion if Republicans had shown an interest, he said.

“If they’d come forward with a plan that ... allowed me to have pieces of all that was in there, I would have been prepared to compromise, but they didn’t. They didn’t move an inch. Not an inch,” he said.

Republicans, of course, dispute that. Collins, in a statement, suggested that Biden had shut down talks under “pressure” from Democratic groups and his staff.

Nonetheless, Americans give high marks to the $1.9-trillion law. By 62% to 34%, Americans approved of it in a recent Monmouth University poll.

It’s not true, as Biden has sometimes suggested, that most Republicans support the legislation, but almost 1 in 4 do, Monmouth found, as do 63% of independents. In these polarized times, that’s a very high level of support from the opposite party.

Biden’s proposal had significantly more support nationwide than did President Obama’s first big economic package, his stimulus plan in 2009, according to an analysis from Third Way, the moderate Democratic think tank.

Beyond the relief package, Biden gets widespread support for his handling of the pandemic — 62% approved in Monmouth’s survey, a level of support that has ticked upward since January.

The partisan divide remains much sharper when polls ask Americans what they think about Biden’s overall job performance. That comes in about 10 points lower — 52% approve in the average of polls maintained by 538.com.

But Biden has another point of bipartisan strength — his personal conduct: Just 27% of Americans had a negative view of how he conducts himself as president, a new survey by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center found.

That’s a marked contrast with former President Trump, for whom personal conduct was a consistent point of weakness, even within his own party. It’s one reason Republicans have had difficulty framing a sharp attack against Biden.

About 40% of Republicans in Pew’s survey said they like at least some aspects of how Biden conducts himself, while just 7% said they agreed with him on most major issues.

Through most of Trump’s tenure, only about 15% of Americans in Pew surveys said they approved of his personal conduct.

That finding highlights an important aspect of how voters respond to Biden’s talk of bipartisanship: Not much evidence shows voters really care whether a law gets support on both sides of the political aisle or even pay much attention to that. They tend to reward success and favor policies that they perceive as fostering it, regardless of the vote count.

What voters don’t like, by and large, is constant partisan squabbling.

Biden’s frequent campaign comments about bipartisanship may have reflected his own nostalgia, but they also provided a way to signal to voters that he would lower tensions in Washington and reduce the level of political acrimony that many Americans disliked about the Trump era.

To that end, one of the most telling pieces of data about Biden’s impact on politics comes not from a poll, but from Google searches.

As Matt Grossman, a political scientist at Michigan State University, noted recently on Twitter, search volume about Trump has dropped a lot since Biden’s inauguration, but searches for Biden haven’t gone up. Instead, all manner of searches about political figures have declined.

For a lot of Americans, Biden has succeeded in making politics boring again, and they’re grateful. That may well be the bipartisan achievement he was looking for all along.

A big week for foreign policy

After weeks in which Biden’s public agenda focused mostly on domestic concerns, this was the week foreign policy took the spotlight.

The main event came Wednesday as Biden declared that it was “time to end the forever war,” and announced that the last U.S. troops would leave Afghanistan by Sept. 11, as David S. Cloud and I wrote.

Although several prominent Republicans, including Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming denounced Biden’s plan, it put the president on the same side as Trump, who had negotiated an agreement for U.S. troops to leave as of May 1. Biden said he would start the withdrawal on that date.

The day before, the White House announced that Biden had invited Russian President Vladimir Putin to a summit while warning him against further aggressive acts against Ukraine. No date has been set, but Biden said he wanted the summit to be held within the next 90 days and suggested it take place in Europe.

In the same phone call Tuesday morning, Biden also warned Putin that he was about to impose sanctions to punish Russia for interfering in U.S. elections, and for its hacking of U.S. computer systems.

As Tracy Wilkinson and Chris Megerian reported, the White House announced those sanctions on Thursday, with Biden saying they were “proportionate” and that the U.S. was not looking for a “cycle of escalation.”

The president also has an international climate summit coming up next week, at which he will try to reassure a skeptical world that the U.S. is back to taking climate policy seriously, as Anna Phillips and Megerian reported.

And on Friday, Biden hosted his first face-to-face meeting as president with a foreign leader, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga.

On another foreign policy front, Noah Bierman and Wilkinson reported on the diplomatic pitfalls Vice President Kamala Harris faces in trying to tackle what the White House terms the “root causes” of migration from Central America. One of those causes is rampant corruption in the governments of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, whose leaders Harris needs to deal with.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The latest from Washington

In a year of reckoning over America’s history of racism, a bill to study slavery reparations moved forward in the House, Erin Logan reported. The bill faces a rough road in the Senate, but the vote by the House Judiciary Committee to send the study proposal to the floor marked a historic first that cheered its backers.

The Senate took up a hate crimes bill this week, with the measure passing a significant procedural hurdle, as Jennifer Haberkorn and Eli Stokols reported. The bill would strengthen federal reporting of hate crimes.

Democratic members of Congress from suburban and wealthy urban areas are pushing to restore the deduction for state and local income taxes, a tax break Californians lost under Trump. But as Sarah Wire reported, California Democrats are taking a softer line on the SALT proposal than their eastern counterparts, largely out of deference to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Biden has quietly reversed Trump’s ban on worker visas under the H-1B program, which is widely used in the tech industry, and the less well known H-2B program, which covers some lower-wage workers. Don Lee looks at how that will affect the U.S. economy.

The pandemic won’t end anywhere until it’s under control everywhere, Doyle McManus writes in his column, laying out the case for international sharing of vaccines.

The latest from California

The effort to subject Gov. Gavin Newsom to a recall is a revolt of red-state California against its blue majority, Mark Z. Barabak writes.

In Sacramento, meantime, Patrick McGreevy writes, lawmakers are pushing to reform the state unemployment agency, whose highly publicized failings have been a drag on Newsom as the jobless face new delays.

Stay in touch

Keep up with breaking news on our Politics page. And are you following us on Twitter at @latimespolitics?

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get Essential Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to [email protected].

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.