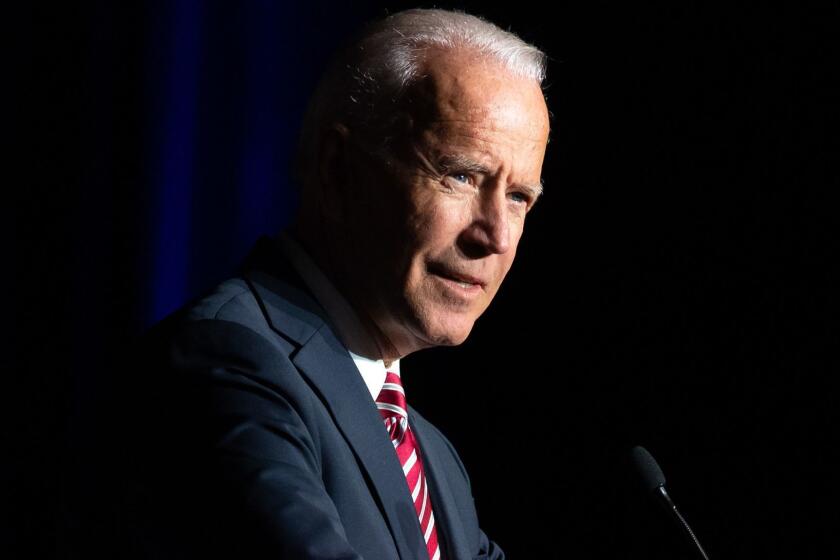

Biden the dealmaker: Can his approach work in a polarized post-Trump America?

WASHINGTON — Joe Biden proudly boasts of how he persuaded Republicans in 2009 to cross the political divide and vote for President Obama’s economic recovery plan.

He doesn’t often mention he only got three or that, in the years since, one has died, one has quit Congress and the third, Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, is in danger of losing her seat this fall.

Even for a consummate dealmaker like Biden, the kind of pragmatic Republicans he’s dealt with in the past are increasingly hard to find.

Biden has put his ability to forge compromises at the center of his quest for the White House, believing that after nearly four years of tumult, weary voters are hungry for a unifying leader, a competent problem solver for a crisis-torn country.

Biden offers his 40 years of experience as a senator and vice president — his relationships, his institutional knowledge, his dealmaking prowess — as the antidote to the chaos created by a brash outsider.

“Compromise is not a dirty word; it’s how our government is designed to work,” he said in a July speech to the National Education Assn. “I’ve done it my whole life.

“I’ve been able to bring Democrats and Republicans together in the United States Congress to pass big things, to deal with big issues.”

But a huge question hangs over that political pitch: Do the political skills Biden honed in pre-Trump America remain relevant to the bruised, battered and deeply divided America of today?

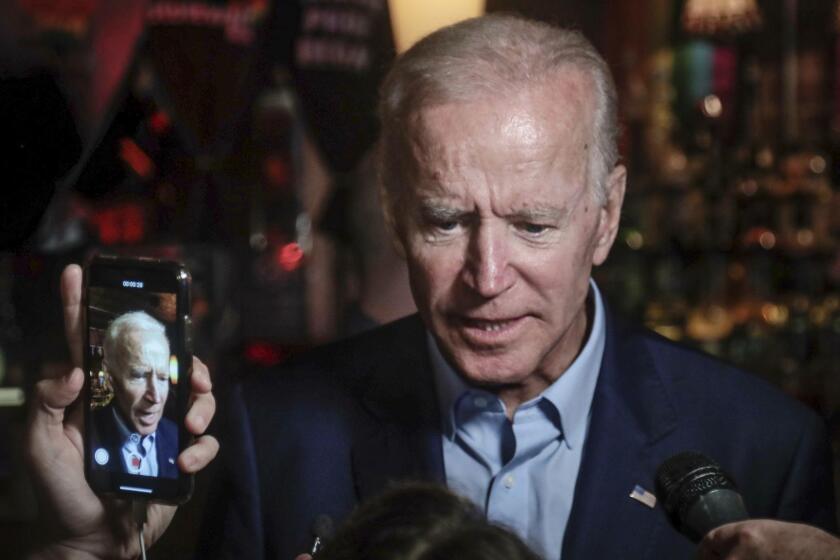

Biden acknowledged the issue at a recent news briefing.

“It’s going to be a lot harder,” he conceded. “Things have changed, a lot harder.”

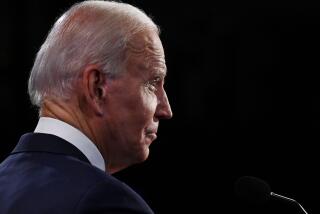

Joe Biden is carrying a 20th century voting record into a 21st century political dogfight.

If Biden wins in November, his hopes of re-creating a more conciliatory era will likely slam quickly into demands within his own party for more radical change on issues like police reform and voting rights and the entrenched tactics of resistance, delay and obstruction that Republicans honed during Obama’s two terms.

If Democrats take control of the Senate, the pressure will build to abolish the filibuster — a defining tradition in the Senate that Biden reveres — if that’s what it takes to get their agenda past GOP opposition. Obama recently used the occasion of the funeral for Rep. John Lewis, a hero to many Democrats, to call for abolishing the filibuster if needed.

Biden himself recently conceded that if Senate Republicans “are as obstreperous as is expected, we’d have to get rid of the filibuster.”

Biden faces a new generation of Republican lawmakers who have come to a more-polarized Washington in the last decade and know little about the dying art of compromise.

“That new group of senators had no reference points to when Republicans and Democrats got along, compromised and tried to work deals,” said former Sen. Chuck Hagel of Nebraska, a Republican who has endorsed Biden.

“That doesn’t mean that can’t be revived,” Hagel said. “If there’s anyone uniquely qualified today to do that, it’s Joe Biden. I don’t know anyone else who has lived that and believed that to his core.”

In many ways, Biden has been preparing his entire political life for this moment. He learned about power, policy and persuasion during 36 years in the Senate. He tried twice to win his party’s presidential nomination — in 1988 and 2008. He flopped both times, but was lifted to the highest levels of government when Obama picked him to be vice president.

All that could make him the man for the moment if voters in 2020 want experience, insider competence, and maybe a comforting blast from the past. A majority of Democratic primary voters did.

“People are craving results and bipartisanship,” said former Sen. Ben Nelson of Nebraska, a conservative Democrat. “Joe Biden fits that bill. Donald Trump does not.”

It’s hard to overstate how much of Biden’s preparation was shaped by the Senate, where he developed a lifelong respect for the possibilities and promise of bipartisanship. That began when the institution gave him an especially warm and emotional welcome in 1973, as colleagues of both parties supported Biden, newly elected and barely 30 years old, after his first wife and child died in a car crash just before he was sworn in.

“I think it’s the greatest institution man has ever created,” Biden said in a 2011 speech at an institute named for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. “I’m still a Senate man. I may be vice president, but it’s still in my blood.”

He learned the key to getting along with both parties from Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-Mont.), in an admonition Biden frequently quotes today: “It’s always appropriate to question another man’s judgment, but never appropriate to question his motives.”

That helped Biden deal with segregationists like Sen. James Eastland (D-Miss.), whom Biden courted to win a seat on the Judiciary Committee. He got the spot at the end of his first term, when Eastland made another offer: “I’ll campaign for ya or against ya, Joe,” Biden related in his memoir, “Promises to Keep.” “Whichever way you think helps you the most.”

During the Democratic primaries, Biden took heat for waxing nostalgic about that relationship.

With a tone-deaf bit of nostalgia Tuesday night, former Vice President Joe Biden ignited a fire around his presidential campaign, speaking wistfully of a time in Washington when he could work civilly with conservatives, including arch-segregationist Sens.

He also recalls cutting deals with GOP Sen. Phil Gramm of Texas to fund Biden’s prized legislation, the Violence Against Women Act. Gramm owed him for a year-old favor: Biden had allowed five GOP district court judge nominations from Texas to be approved right before the 1992 presidential election; if Biden, then Judiciary Committee chair, had delayed, the vacancies would have been filled by a Democratic president.

That’s a stark reminder of how things have changed: In 2016, McConnell refused to allow a vote on an Obama Supreme Court nominee for eight months before the presidential election, leaving the seat vacant until after Trump was elected. That has come to be seen as a defining moment in the polarization of Washington.

Biden’s decades of experience in Congress came in handy in the Obama administration, when he became the uber-liaison to Capitol Hill for a president who did not like that part of the job.

One of Biden’s first challenges was to round up support for Obama’s economic rescue plan — a tough job at a time when Republicans had made clear they had no interest in cooperating with the young, new president. The entire House GOP conference voted against the plan; the three GOP senators who came along were just enough to pass it.

Biden took a particular interest in nailing the vote of Sen. Arlen Specter (R-Pa.), with whom he enjoyed a bipartisan friendship, which has become increasingly rare.

Biden badgered Specter with relentless phone calls seeking support for the bill. “He played it like man-to-man coverage in a basketball game,” Specter said in his memoir.

Biden also helped persuade Specter, who was up for reelection in 2010, to switch parties soon after the vote. That did not work out well: In a harbinger of greater polarization to come, Democratic voters rejected Specter in a primary.

Near the end of 2010, Biden struck a major budget and tax deal with McConnell, which began with an unsolicited call from the vice president to the majority leader. Liberal critics said he gave too much away, especially with a cut in the estate tax.

McConnell attended the bill-signing ceremony; House and Senate Democratic leaders did not.

“As far as Republicans were concerned, the deal was terrific,” McConnell gloated in his memoir.

In 2012, when another crucial budget deadline loomed and negotiations had broken down, McConnell called Biden.

“Is there anyone over there who knows how to make a deal?” McConnell asked.

Liberal critics charged that McConnell sought him out as a negotiating partner because he was an easy mark.

But McConnell, in his memoir, said he reached out because Biden was a more effective negotiator than Obama.

“Joe ... made no effort to convince me that I was wrong, or that I held an incorrect view of the world,” McConnell wrote. “He took my politics as a given, and I did the same.”

Already by that point, the nation’s partisan lines had hardened. Since Biden’s career began, Republicans have moved right, Democrats to the left, and voters have increasingly sorted themselves into two hostile camps that divide not just by party, but also along lines of race, education and religion. The Trump years have widened the divide further.

In that environment, compromise can often be seen as betrayal.

“Washington is now dominated on the right by folks who listen to the hard-right, irrational, no-compromise view,” said former Sen. Judd Gregg (R-N.H.), “and on the left by hard-left, irrational, no-compromise view.”

Early on in the campaign, Biden seemed to try to blink away that reality. He said that after Trump left office, Republicans would have an “epiphany” and become easier to deal with.

Fellow Democrats called him naive, and Biden has not said that for some time, but whether he has changed his mind remains unclear.

The next president will likely take office in dire circumstances, with a pandemic still raging and the economy ailing, which could perhaps open the door to bipartisan action.

But Gregg and others believe that even with Biden’s experience, the future is likely to look more like the congressional stalemate this month in which economic relief programs for millions of Americans lapsed because the two parties could not agree on a compromise.

“When I see Biden saying he wants to work with Republicans to get things done, he is being serious,” said Eli Zupnick, a Democratic strategist who worked for years in the Senate. “But Republicans are not serious about working with him.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.