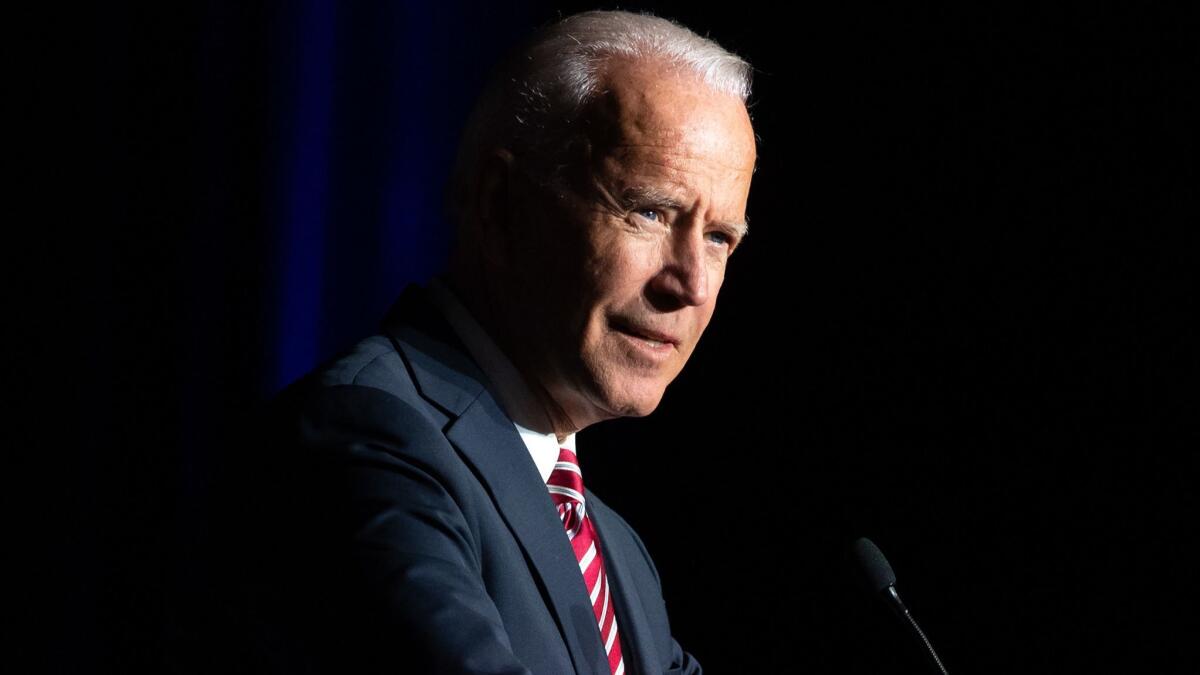

The burden of a 40-year career: Some of Joe Biden’s record doesn’t age well

Reporting from Dover, Del. — Joe Biden is carrying a 20th century voting record into a 21st century political dogfight.

During more than 40 years in public life, Biden has taken an array of stances at odds with today’s Democratic Party consensus. As he now prepares for his third presidential campaign, that record could hamper him in a big field of mostly younger, more liberal primary rivals.

A review of Biden’s record — which spans 36 years as a U.S. senator and eight as vice president — is, in part, a reminder of how much the Democratic Party itself and the U.S. political system have changed over the last half a century.

Biden opposed school busing for desegregation in the 1970s. He voted for a measure aimed at outlawing gay marriage in the 1990s. He was an ally of the banking and credit card industries.

He chaired the 1991 Clarence Thomas hearings that gave short shrift to the sexual harassment allegations raised by Anita Hill. He backed crime legislation that many blamed for helping fuel an explosion in prison populations. He eulogized Sen. Strom Thurmond (R-S.C.), who rose to prominence as a segregationist. He backed the Iraq war.

Many of Biden’s positions were well within the mainstream of the Democratic Party at the time he took them.

But the party is now far more sensitive to discrimination against gays, sexual harassment and racial inequality than when Biden first came to Washington.

The capital has changed, too. The Senate Biden entered as a 30-year-old in 1973 was still a bastion of bipartisan backslapping, where compromise was not a dirty word. The Democratic Party was a coalition of Southern conservatives and Northern liberals. Liberal Republicans were still a thriving political faction.

Biden’s record, even though he has reversed himself on some issues, provides ammunition to skeptics who see him as a politician of another era — a beloved figure, but one whose time has come and gone.

“I worry whether he is ready for the times,” said Chris Schwartz, a Black Hawk County supervisor in Iowa who says Biden is not in his top five choices among the candidates but is prepared to support whoever is nominated. “He has just gotten too many big issues wrong over the years.”

But most Democratic voters put their top priority on beating President Trump, and Biden allies say he is the best equipped to win. Polls show Democrats are still fond of Biden and seem more willing to forgive him for his past than they ever were for Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Democrats, facing a big candidate field, ask: Who can beat Trump? »

“I’ve seen Biden change; all of us have seen our parents, our aunts and uncles change,’’ said Jane Kleeb, chair of the Nebraska Democratic Party who is neutral in the 2020 race but supported Bernie Sanders in the 2016 Democratic primary.

“I don’t think it says who he is today,” Kleeb said of some of the flashpoints in Biden’s voting record.

If Biden, 76, formally enters the race — he has strongly hinted he will do so in a matter of weeks — the question will be which of those attitudes will prevail.

Speaking at a dinner of the Delaware Democratic Party in Dover on Saturday night, Biden responded to criticism of him from what he called “the new left.”

“I have the most progressive record of anybody running,” said Biden, who quickly revised his words when the audience reacted as if he were announcing his candidacy. “Anybody who would run. I didn’t mean it.”

But his speech sounded like a campaign stump speech, and other Democrats treated his eventual entry into the race as a foregone conclusion.

“If you ask me he doesn’t just look like he’s back,” Delaware Gov. John Carney said of Biden. “He looks like he’s ready for a fight.”

Biden would join a big field of Democratic candidates that spans four generations, from millennials including South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, 37, to Silent Generation member Bernie Sanders, 77. The latest entrant to the field, former Rep. Beto O’Rourke, is a Gen Xer 30 years younger than Biden.

Who’s running for president and who’s not »

Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.) said he hoped that scrutiny of Biden’s Senate record would not distract from Biden’s core 2020 message.

“I think that getting down in the weeds of things he might have said literally 40 years ago misses the point that Donald Trump literally yesterday said something about white nationalism that is gravely concerning,” Coons said in an interview before the Dover dinner. “I am happy to defend his record in detail, but as a candidate he should and will focus on how his experience combined with his heart and character make him the right person for leading us.”

If rivals do criticize his past record, Biden allies say context will be important to understanding it. A majority of Democrats in the Senate voted for the anti-gay-marriage bill, the Iraq war and the 1994 crime bill. The banking and credit card industry is important to the economy of Biden’s home state of Delaware.

Ed Rendell, a Biden supporter who is former chairman of the Democratic National Committee, says the former vice president’s campaign should address questions about his past positions in a simple stroke.

“He should say, ‘Look, those were the beliefs that were commonly held, even among progressive people, back 30 years ago,’ ” Rendell said. “‘In retrospect they were clearly wrong. My views on those subjects have evolved. Period.’”

That is an easy argument to make on the matter of gay rights. In 1996, Biden was one of 32 Senate Democrats to vote for the Defense of Marriage Act, which defined marriage as a union between a man and a woman. In 2012, as vice president, he stepped out in favor of same-sex marriage even before President Obama did. He has taken other steps since then to advance gay and transgender rights that have made him something of a hero to the LGBTQ community.

Danny Barefoot, a Democratic political consultant who is not affiliated with any 2020 presidential candidate, recently conducted a focus group with black women in South Carolina and found that negative messaging about Biden’s record did not ring true to these loyal Democrats, especially on questions related to his commitment to civil rights.

Presented with reports about his opposition to school busing in Delaware in the 1970s, one woman asked “if we’re honestly asking her to believe he is a segregationist,” Barefoot wrote.

But he found Biden might have more work to do putting to rest questions about his handling of Hill’s sexual harassment claims against Thomas.

The focus group unanimously said Biden needed to personally apologize to Hill. As chairman of the all-male Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991, he was criticized for not pursuing more aggressively the sexual harassment allegations Hill raised.

That is one of several areas where Biden has already taken some steps to make amends.

“Anita Hill was vilified, when she came forward, by a lot of my colleagues, character assassination,” Biden said on the “Today” show in September 2018, around the time the Senate was grappling with sexual assault allegations against Supreme Court nominee Brett M. Kavanaugh.

“I wish I could have done more to prevent those questions and the way they asked them.”

But Hill, who declined a request for an interview, said in a December 2018 interview with Elle magazine that Biden had not apologized to her directly.

“It’s become sort of a running joke in the household when someone rings the doorbell, and we’re not expecting company,” she told Elle. “ ‘Oh,’ we say, ‘is that Joe Biden coming to apologize?’ ”

Biden has also revised his thinking on some tough-on-crime and anti-drug measures of the 1980s and 1990s. At a Martin Luther King Jr. Day breakfast in January, he expressed particular regret for a bill that created different legal standards for powdered cocaine and street crack cocaine.

“It was a big mistake that was made,” Biden said of the disparity, which the Obama administration worked to reduce. “We were told by the experts that crack, you never go back, that the two were somehow fundamentally different. It’s not different. But it’s trapped an entire generation.”

He makes no apologies for his good old-fashioned willingness to work with Republicans — a trait that could endear him to many voters impatient with partisan stalemate in Washington.

When he was asked to deliver the eulogy for former Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond in 2003, Biden joked about their implausible relationship and called the late senator’s request for him to speak “his last laugh.”

“I disagreed deeply with Strom on the issue of civil rights, and on many other issues, but I watched him change,” he said in the eulogy.

More recently, he drew fire from the left for referring to Vice President Mike Pence as a “decent guy.” And during the 2018 midterm campaign, he publicly praised a House Republican, Fred Upton, for his work on a cancer research bill dear to Biden, whose son died in 2015 of brain cancer. The praise of Upton troubled some Democrats because they were trying to defeat him, and he cited Biden’s words in debate with his Democratic opponent.

Biden bridles at criticism of his bipartisan gestures. “We don’t treat the opposition as the enemy,” Biden said in the Dover speech. “We might even say a nice word every once in a while about a Republican when they do something good.”

But paeans to bipartisanship can be like fingernails on a blackboard to the combative Democratic left — especially among voters too young to have known a less polarized political environment who are gravitating to the party’s more liberal candidates.

Kristina Hughes, 30, an Omaha voter who is attracted to Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren said, “Anybody who says Mike Pence is a decent guy doesn’t get my vote in 2020.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.