Column: Newsom recall is a revolt of red-state California

In the 170 years that California has been a state, there have been more than 200 attempts to break it apart.

In the rural north, residents have long chafed at the laws coming out of Sacramento and the power and influence emanating from the state’s big cities. Far from Los Angeles and San Francisco, amid the buttes and sugar pines, there are dreams of a land called Jefferson, a 51st state formed by splitting off from California and hitching up with a chunk of southern Oregon.

In Silicon Valley, Tim Draper, a Republican venture capitalist with more money than political success, has spent millions of dollars peddling plans to subdivide California into several mini-states he considers more governable than the present day behemoth. One proposal made the November 2018 ballot until the state Supreme Court quashed it because of doubts about the measure’s validity.

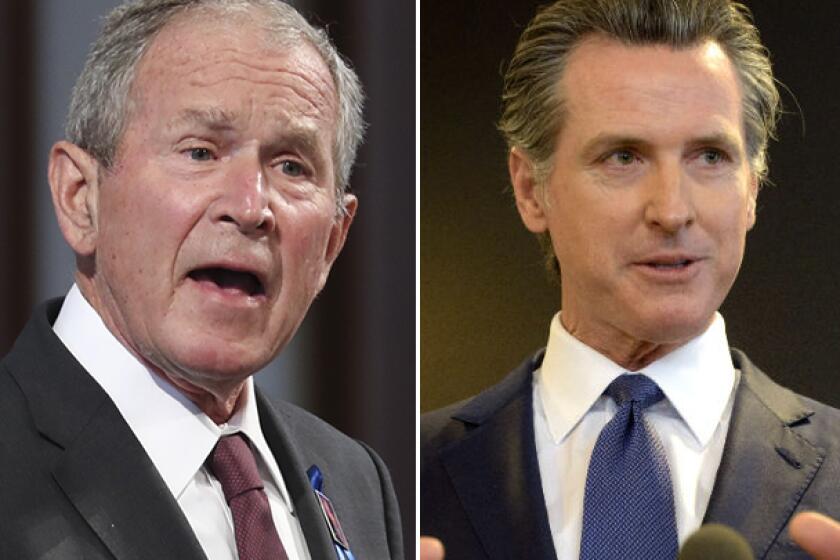

The effort to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom is driven by the same unhappy impulse among Californians feeling outnumbered, outvoted and underrepresented. It’s the revolt of red California against the state’s blue political and cultural establishments.

The GOP investment plays into Democratic efforts to cast the recall as a partisan power grab.

Polls show, not surprisingly, that Republicans — an increasingly endangered species in California — overwhelmingly back the effort to oust the Democratic governor. Most Democrats are just as strongly opposed.

The greatest support for the recall, based on the percentage of voters who signed qualifying petitions, has come from the most conservative quarters of California. More than 15% of registered voters in sparsely populated Amador, Glenn, Calaveras, Siskiyou and Tuolumne counties signed qualifying petitions, according to numbers crunched by the San Francisco Chronicle. That’s State of Jefferson territory.

By contrast, just 3% of registered voters in crowded Los Angeles County signed a recall petition. The figure was 2% in two other major population centers, Alameda and Santa Clara counties, and less than that in San Francisco. Of the state’s 10 most populous counties, the percentage of registered voters backing the recall hit double digits in just two, Fresno and Riverside.

Not incidentally, those are the only two that Republican John Cox carried — barely — in his crushing loss to Newsom in 2018. Cox is among those running to replace the governor.

Dave Gilliard, one of the strategists leading the effort to oust Newsom, noted that signature-gatherers focused their labors, quite reasonably, on the areas likely to yield the most fruitful results. Signatures are being validated by county election officials, and an announcement on whether the recall makes the ballot is expected by the end of the month. It seems nearly certain to qualify.

For recall proponents, that’s when the hard work begins.

Newsom beat Cox by landslide margins in the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles County, where most voters reside. It’s impossible to see how the recall passes with just the support of discontented rural Californians, even if every single would-be citizen of Jefferson were allowed to vote twice.

A March survey by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California found the recall failing by big margins in the state’s blue bulwarks. Even in the more moderate Central Valley and Inland Empire, fewer than half those surveyed said they would vote to kick Newsom from office. Overall, 4 in 10 supported the recall and 56% were opposed.

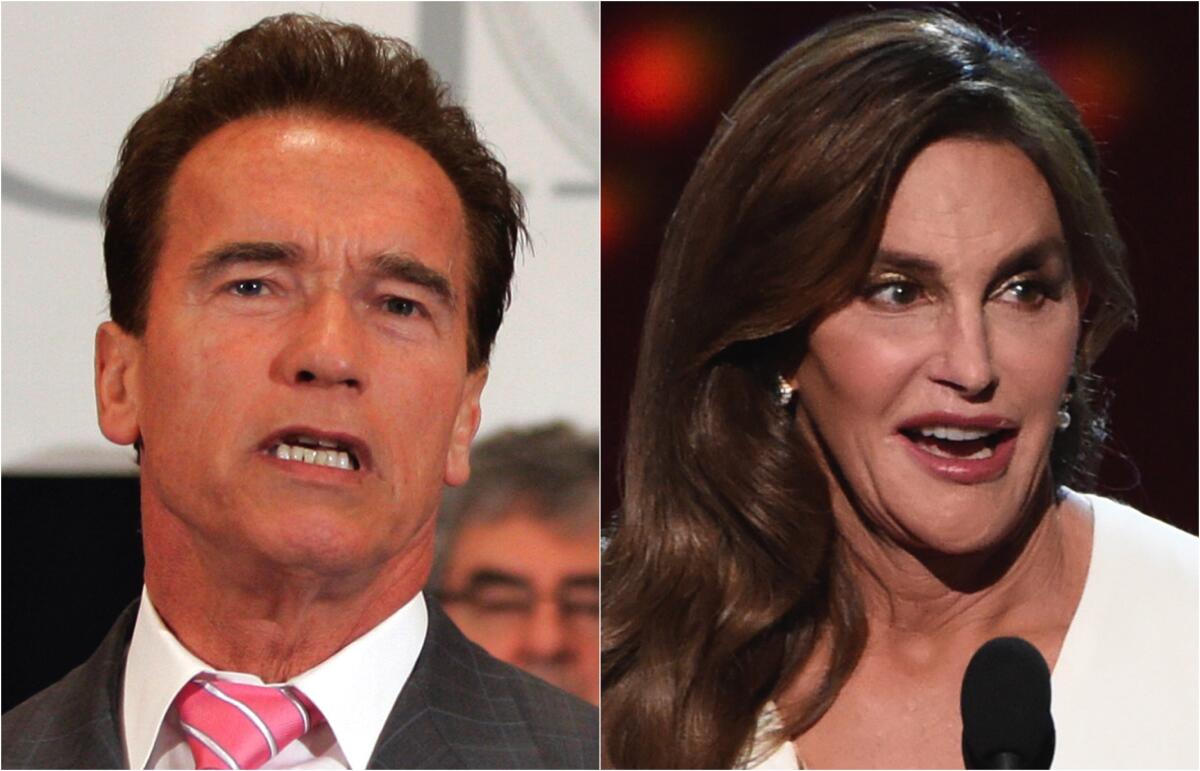

People could change their minds. In an April 2003 Field Poll, nearly 6 in 10 said they considered the recall of the state’s unpopular governor, Gray Davis, to be a bad idea. Even so, 46% said they would support his removal. Six months later, 55% voted to replace the Democrat with actor Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Much will depend on the candidates vying to replace Newsom. (Though nothing will matter so much as the state of the economy, whether public schools have reopened and if the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have passed by the time voters fill out their ballots.)

Fascination has lately alighted on the prospective candidacy of athlete-turned-reality-TV-star Caitlyn Jenner, though, it should be said, if media captivation translated into votes, former child actor Gary Coleman or adult film actress Mary Carey might have been elected governor in 2003.

Reports of the state’s decline and fall are a cyclical staple. Blame it on envy and partisanship

There is widespread misapprehension regarding Schwarzenegger’s success. Much of his appeal was based not so much on celebrity as his stance as a political outsider — and, not least, perceptions he transcended both major parties.

It turns out, however, that experiment in learn-as-you-go governing didn’t end so well; by the time Schwarzenegger left office his disapproval rating had reached 70%, which — the irony! — is where Davis stood just before he was fired by voters.

Given that, it’s questionable whether Californians wish to go the tabloid-governor route a second time.

It also doesn’t help that Jenner’s candidacy includes heavy input from associates of former President Trump, including a fundraiser, Caroline Wren, who helped organize the rally that preceded the deadly Capitol insurrection.

Even Gilliard, who was careful to not endorse a candidate in the recall, suggested the twice-impeached ex-president was a dead weight.

“If the election is about Donald Trump, we won’t win,” he said. “If the election is about Gavin Newsom’s performance in office and whether or not Californians want to continue with that or try someone else, then we win.”

If, that is, enough voters in blue California decide to make a change, and the recall becomes more than just another red-state rebellion.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.