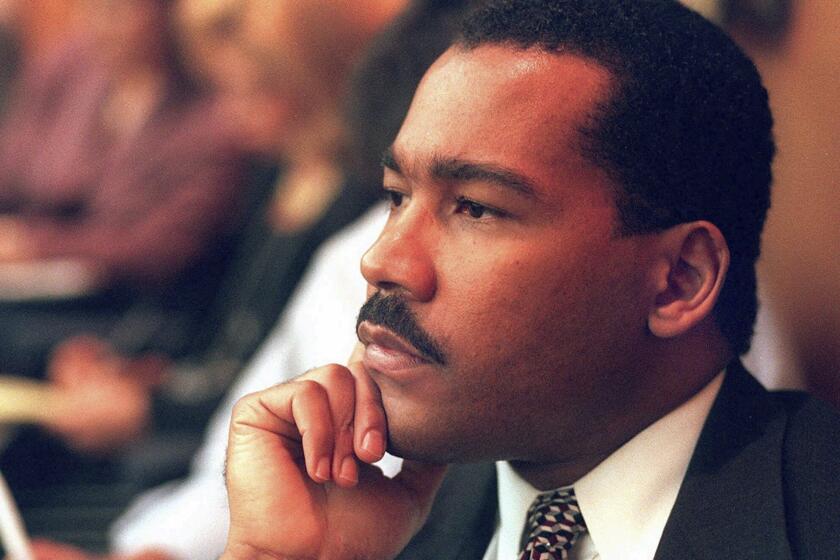

Roland Coleman Jr., former L.A. County Bar Assn. president, dies at 74

Attorney Roland Lee Coleman Jr., the second Black person to lead the Los Angeles County Bar Assn., has died. He was 74.

Coleman also served as president of the John M. Langston Bar Assn. of Los Angeles, founded in the 1920s to serve and support Black lawyers excluded from other bar associations.

Coleman once recounted being told that a Black attorney couldn’t win cases in Glendale or Fullerton. In the face of racism, “I really believed I had to be better than anybody else,” he said.

In the courtroom, “he knew every rule backward and forward,” said Ian Stewart, an attorney who worked with Coleman at the law firm Wilson Elser. But “his style was one where he could really connect.”

He was tenacious, Stewart said, but “he’d do it with a smile on his face.” If you were on the opposite side of a legal battle, “you’d end up shaking hands and walking away buddies.”

Coleman grew up in Los Angeles, one of four children. As a teenager at Los Angeles High School, he was “perhaps the most popular person on campus,” said Earl E. Thomas, a friend and fellow attorney. Jackie Herod, another longtime friend, said he was known as a sharp student who ran long distance and joined an array of clubs, including cheerleading and debate.

Thomas said that at parties, “Roland would get in the middle of the floor, and he would start dancing,” doing the newest moves as everyone formed a circle around him to watch. “A lot of people would say the party didn’t start until Roland got there.”

Coleman graduated from the University of Southern California and Loyola Law School. He worked for the Los Angeles city attorney’s office and then for the California Department of Transportation before being hired at Wilson Elser, where he became a partner.

“He was a superstar,” said Pat Kelly, who hired Coleman at the firm and worked closely with him. “He could simplify difficult issues and explain them in a commonsense way.”

Beyond the courtroom, Coleman volunteered to assist L.A. County residents as freeway construction was “wreaking havoc on the citizens in the community,” helping them to address complaints about noise and other hazards, said U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles).

With his help, “we forced Caltrans to set up an office right in the community where they could deal with complaints,” Waters said. And when residents were being displaced, “we were able to force them to increase the offers for those homes. ... Roland was basically responsible for all of that.”

Coleman “just took it on like it was his job,” said retired Superior Court judge John Meigs Sr., who became friends with him as a law student.

As president of the Langston Bar Assn., Coleman started a hall of fame to honor people in the legal profession who “persevered, sacrificed and — in spite of those obstacles and those hardships — succeeded,” said retired judge Allen Webster, another former president of the association.

Louis Gossett Jr. won an Oscar for ‘An Officer and a Gentleman’ and an Emmy for ‘Roots.’ The 87-year-old actor died Thursday night in Santa Monica.

After the 1991 killing of Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl who was shot by a Korean-born shopkeeper, the Los Angeles County Bar Assn. was divided on a recall campaign against Judge Joyce A. Karlin, who sentenced the shopkeeper to probation. Coleman later told the Metropolitan News-Enterprise that many in the Los Angeles County Bar Assn. saw the recall effort as an attack on the independence of the courts.

“I appreciate the independence of the courts, I understand the desire for that. But these kinds of concerns of respect have to be a two-way street,” Coleman recalled telling leaders of the association. Courts “have to respect the people who appear before them.”

The association decided not to weigh in against the recall.

“Inwardly, he was sensitive to the feelings and needs of others. Outwardly, he was fearless and fierce in his commitment to friends, family and community,” his sister Carmen Freeman said.

Coleman led the L.A. County Bar Assn. from 2001 to 2002, the second Black person to hold the position since the group was founded in 1878.

As president, “his focus was, ‘How can we better help the community that we serve?’” said Danette Meyers, an attorney who was active with the association.

During his presidency, Coleman pledged to make attorneys available pro bono to assist victims of discrimination, joining state officials at the announcement of a hotline to report hate crimes. He also worked to improve public access to legal services.

“His voice had a lot of credibility,” said Miriam Krinsky, who followed him as county bar association president. “When he chimed in on an issue, I really wanted to make sure that I was listening closely.”

Later in life, Coleman suffered from health problems and endured years of frustration as he tried to get onto the waiting list for a donated kidney. The Times chronicled his ordeal, which included tangling with a health insurance company over where he could be evaluated for a possible transplant.

Coleman decided to switch insurance plans to improve his chances and started driving for a ride-share company to pay for higher premiums. He told The Times that on his first day as a driver, he began chatting with a passenger he picked up in North Hollywood, who promptly offered to donate a kidney if approved.

“There was never a stranger in Roland’s life,” Herod said.

Coleman never got a kidney transplant. But even as he grew increasingly ill, he could make Herod laugh during phone calls.

“He would say, ‘Jackie, if you see a kidney running around, catch it. Catch it for me, and I’ll pick it up.’”

Coleman is survived by his wife, Evelyn Jenkins Coleman, son Roland Coleman III (also known as R.J.), stepson Jeremy Jenkins, sister Carmen Freeman and brother Lorin Coleman.

Dexter Scott King, the younger son of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King, has died after battling prostate cancer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.