Column: The killing of Latasha Harlins was 30 years ago. Not enough has changed

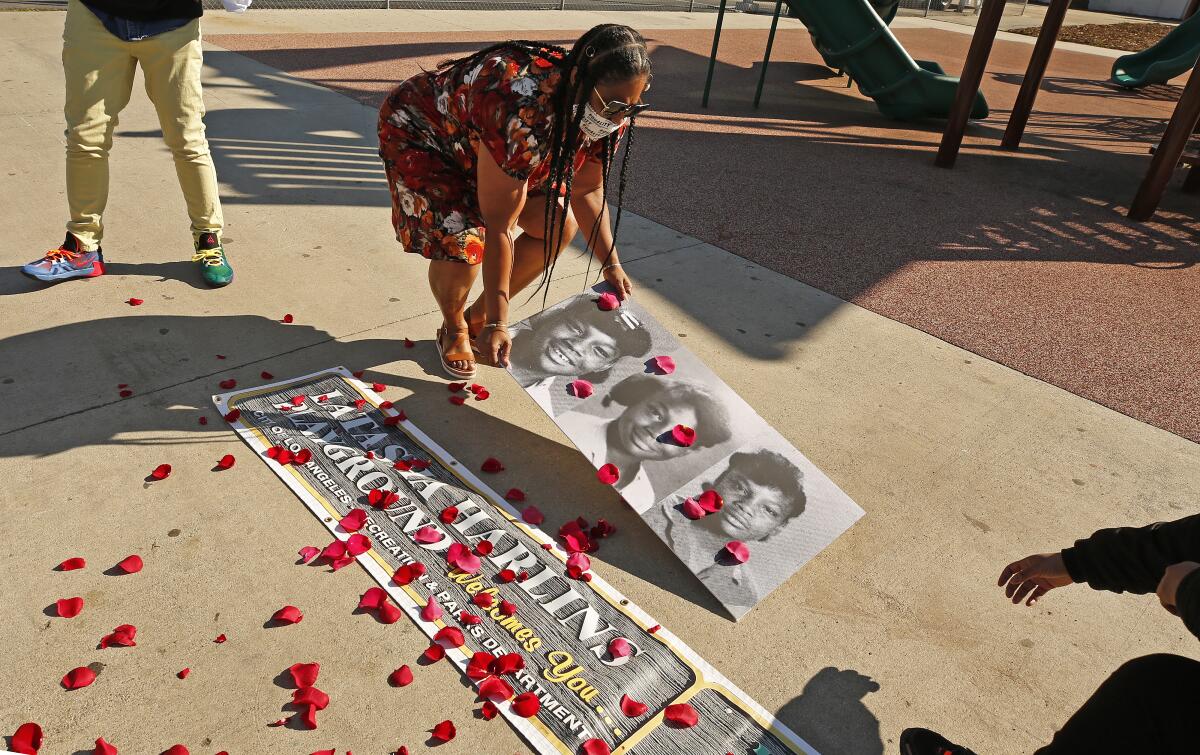

For the second time in three months, the people who knew Latasha Harlins best and who miss her most gathered in front of her mural at Algin Sutton Recreation Center.

Thirty years ago, the 15-year-old Black girl from South Central walked into Empire Liquor Market and Deli, grabbed a $1.79 bottle of orange juice and put it in her backpack. A Korean-born merchant, Soon Ja Du, accused her of stealing it. Latasha had $2 in her hand.

Du grabbed Latasha’s sweater. Then Latasha punched Du in the face and headed for the door. Du picked up a handgun and fired a shot into the back of Latasha’s head.

Police later confirmed that there was “no attempt at shoplifting.” A jury found Du guilty of voluntary manslaughter, but instead of serving a maximum of 16 years in prison, Judge Joyce A. Karlin gave Du probation. For killing a 15-year-old girl who was walking away from her.

It’s a story that rocked Los Angeles at the time. But nationally, it was mostly lost in the coverage of four white police officers beating the hell out of Rodney King in the middle of a street, which had happened less than two weeks before Harlins was shot. As someone who didn’t grow up in California, I can attest to how much more coverage the King beating got.

And now, after three decades and one generation of activists giving way to a younger set, Latasha’s story is even beginning to get lost in Los Angeles.

Thirty years is a long time. Long enough for some things to change, but not nearly enough.

For every law that has been passed to reform the criminal justice system and for every protest that has happened under the banner of a Black Lives Matter movement that didn’t exist when Latasha died, her story remains infuriatingly relevant. As her grandmother, Ruth Harlins, put it, “The shooting and killing of African Americans is still going on.” And for most, justice remains elusive.

We still have Ahmaud Arberys and Breonna Taylors, young people with promising lives that were cut short with little guarantee of recourse from the criminal justice system. Latasha, who wanted to be an attorney and help kids in South L.A. when she grew up, was just one of many.

The weight of that unfairness, along with the glaring passage of time, seemed to haunt those who spoke alongside the mural on Tuesday.

They came to a bank of microphones, one by one. Ruth, who helped raise Latasha after her mother was fatally shot in a nightclub in 1985, gingerly stepped away from her walker to speak, occasionally gazing up at the massive smiling face of her granddaughter.

“Let me give honor to the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost,” she said. “And I just thank him for giving me the strength to again honor my granddaughter.”

Shinese Harlins Kilgore, Latasha’s cousin, tried not to get too emotional during the dedication. But that didn’t quite work. She quickly broke into passionate chants of “no justice, no peace” when talking about Latasha.

“Thirty years ago, we were stereotyped all the time,” she said. “And I believe we’re still stereotyped all the time.”

Of course, Asian Americans are unfairly stereotyped, too — sometimes with horrific and violent results. This is especially true these days because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s entirely possible, though not yet certain, for example, that the six women of Asian descent who were shot to death in the Atlanta area on Tuesday are the latest victims in a surge of hate crimes and harassment cases across the U.S.

Shinese also talked about what has changed since 1991. Everywhere, she said, Black people are united in the same fight as her family — for justice and against systemic racism.

“I think we’re ready to go to war. We ready to fight for equal rights now,” she said. “It just depends on how hard we fight to see the change that we want. We’ve got to stay consistent like the Black Lives Matter movement.”

Latasha’s younger sister, Christina Rogers, agreed. But she said it’s perhaps even more important that Americans of all races and ethnicities now have a deeper understanding of how systemic racism and white supremacy work in this country — and in all sorts of daily interactions, even going to the store to buy orange juice.

Because of this, Rogers predicted there would have been true “chaos” if Latasha had been shot in the head in 2021, rather than 1991. While many in South L.A. point to what happened at Empire Liquor Market and Deli as being the real spark for the 1992 riots, it never led to the sort of national outrage and calls for reform that Rodney King’s beating caused.

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“Back in 1991, we didn’t have social media,” she said. “We didn’t have Facebook.”

In short, over the past 30 years, whatever has changed has started with greater public awareness. It has made all the difference. And that’s what Latasha’s family wants for her, even if it has to be in death.

Things are already moving in the right direction.

After weeks of lobbying the city, artist Victoria Cassinova was able to paint the mural of Latasha on the side of Algin Sutton Recreation Center. The family saw it for the first time on New Year’s Day, which would have been the late teenager’s 45th birthday.

Then Monday, “A Love Song for Latasha,” a 19-minute documentary about her life, was nominated for an Oscar. And Tuesday, the city officially renamed the playground at Algin Sutton Recreation Center after Latasha. The sign hasn’t been installed yet, but Christina called it “breathtaking.”

Latasha Harlins, an L.A. teen who was killed in 1991, is at the heart of ‘A Love Song for Latasha,’ which was nominated for the documentary short Oscar.

Shinese, meanwhile, was moved to tears. The playground is where she and Latasha played as children. It’s the sort of memorial her late mother, Latasha’s aunt, Denise Harlins, would’ve wanted.

“Mississippi has Emmett Till. Florida’s got Trayvon Martin,” L.A. City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson said, announcing the renaming. “Los Angeles has Latasha Harlins.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.