Years into his quest for a kidney, an L.A. patient is still in ‘the Twilight Zone’

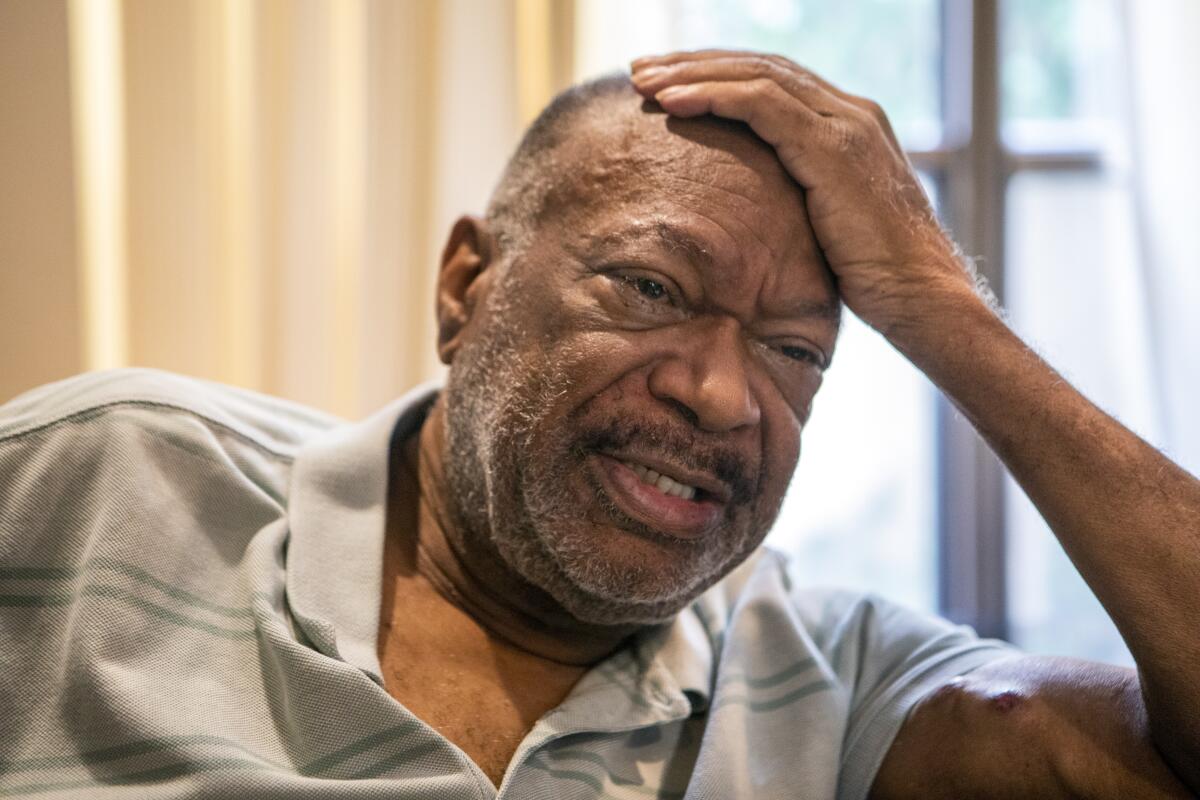

In his Arcadia home, Roland Coleman grew increasingly frustrated as the months passed without an answer from Keck Medical Center of USC.

Coleman, 73, was seeking a kidney transplant to free him from his listless afternoons undergoing dialysis and lengthen what remains of his life.

Keck had indicated, in an educational video for transplant seekers, that the evaluation process could take up to six months. One year after Coleman went to Keck’s Los Angeles campus for an orientation on its kidney transplant program, a Keck coordinator assured him in an email that “the team is reviewing your case.”

Then in August — more than a year and a half after his Keck orientation — Coleman was told that his evaluation was closed. In a letter, Keck told Coleman he was too “high risk” to be a transplant candidate at that time, but said it might reconsider him if he took some additional steps.

Coleman, a “semi-retired” attorney who once served as president of the Los Angeles County Bar Assn., vigorously disputed their statements. For instance, Keck raised concerns about a medical condition requiring the use of blood thinners, but Coleman pointed to documents indicating he had gotten an implant that eliminated the need to take them.

Keck also said he needed to get psychiatric care for depression and anxiety, but Coleman countered he had previously seen a psychiatric professional and was taking medication — facts already laid out in a Keck assessment.

To have even a chance at a kidney from a deceased donor, an ailing patient needs to get onto the waiting list. But fewer Americans on dialysis have that chance.

In a string of emails to the program, Coleman complained that Keck seemed unaware of information it had in its own records, saying that “you have all you need if someone would just read the material.” He was galled that he was being asked to reconnect with a psychiatrist, saying that he would not have needed to do so if Keck had not dragged its feet.

An earlier evaluation, he pointed out, had found that getting a kidney transplant could ease his depression. Even more urgently, studies have shown that getting a kidney transplant is tied to a lower risk of death than staying on dialysis.

“I have lost over a year during this tenuous period in my life,” he wrote. “Medical treatment delayed is medical treatment denied.”

Keck said every patient referred there for a kidney transplant is assigned a coordinator who communicates with them about their progress, but by last fall, Coleman said he wasn’t sure who his coordinator was because the program had endured so much turnover. As of that time, he had had three coordinators over the course of his evaluation, according to the medical center.

The transplant program said its evaluation process can be delayed “due to issues with insurance approvals, outstanding records, or lapsed communication” between the patient and a coordinator, and such delays had been exacerbated amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

The medical center said that Coleman, who provided consent for Keck to discuss his medical history with The Times, could still be assessed as a candidate after it sent the August letter, but there had been inconsistencies between his claims and its existing records, and that it needed more documents to reconsider his eligibility.

Keck said it had reached out to Coleman to tell him documents were needed in the months before its August decision, including by email in July, but did not provide a copy of such a message to The Times. Coleman said he had not gotten any messages asking for specific documents before the fall.

An influential scientific advisory panel says the U.S. transplant system needs an overhaul to stop wasting organs and give more patients a fair chance.

In September, he told Keck he had already provided a release to get any medical records they needed. A Keck representative told him that they had made efforts to do so, but “the ultimate responsibility for providing all required records lies with you as the patient.”

Fed up with Keck, Coleman decided to undergo evaluation at another center. By early March, roughly five months after he was connected to the Providence St. Joseph program based in Orange, he was eagerly anticipating a decision on whether he could get onto the waitlist after a series of appointments, pleased that the process had moved faster there.

Then he was thwarted again.

Insurance company UnitedHealthcare had sent a letter granting approval for Coleman to go to Providence St. Joseph, but hospital officials said that when they sought to confirm his health insurance would cover his care after transplant — a step it takes before having a selection committee decide whether patients are waitlisted — they hit a roadblock.

Providence St. Joseph officials said UnitedHealthcare told them it made a mistake when it authorized Coleman to go there in September. Coleman needed to go to a transplant center in its network, it said, and that did not include Providence St. Joseph.

“We really advocated, saying that, ‘We’ve done this entire evaluation. The patient is established with us. He’s happy with us,’” and tried to get approval for Coleman to get a transplant there, said Wendy Escobedo, director of nursing in dialysis and transplant for Providence St. Joseph.

Coleman was especially frustrated because he said UnitedHealthcare had pointed him there. “They called me and told me, ‘Oh, we’ve got another program for you,’” he said.

A UnitedHealthcare spokesperson said, “We are working with Mr. Coleman to help him find a facility in his area for a transplant evaluation.” As of March, the insurance company said it had granted authorization for Coleman to be evaluated at Keck and at UCLA.

More than two years have now passed since he first went to Keck to seek a transplant. Keck said in March that it had received documents that it needed and could reevaluate him as a candidate. Among the documents that Keck had received: one from a cardiologist stating that the risk of cardiac complications surrounding the surgery for him should be low.

But soon afterward, Keck said it was closing his case. It said that UnitedHealthcare affiliate Optum did not allow him to be evaluated at two programs, so moving forward with UCLA would prevent him from proceeding with Keck. Coleman worried about how much time restarting the process at UCLA could take, and how much time he now has left.

“I’m in a ‘Twilight Zone’ where I don’t know who’s going to do what,” he said, “or when.”

After The Times reached out to UnitedHealthcare and Optum about their rules, Coleman said he got a phone call from Optum saying he could be evaluated by both UCLA and Keck.

He later heard from Keck that his evaluation there could proceed, he said.

Coleman, as a seasoned attorney, is equipped to argue his case in ways that many patients are not. He has lodged complaints with regulatory bodies and is weighing possible lawsuits against Keck and UnitedHealthcare. As a lawyer, he has defended product manufacturers, which often involved questioning medical experts in court.

And as a Black man who had to endure racist insults during his career as an attorney, “what I had to do was be the best,” Coleman said.

But years into his quest for a kidney, he said he felt defeated. “I shouldn’t have to do all this,” he said in an interview last fall at his Arcadia home, describing the hurdles he had faced at Keck. His blood pressure had been low that afternoon. At one point, he paused and put down his head, apologizing for not being at his best.

“I’m the sick one.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.