Argentina mystery: Unsolved terrorism case, and the prosecutor’s death

Reporting from Buenos Aires — Three weeks after the death of an Argentine prosecutor investigating the bombing of a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires, details surrounding his demise are as murky as the labyrinthine case he was examining, which is still unsolved after more than 20 years.

Alberto Nisman, who was in charge of the inquiry on the 1994 attack, was found dead Jan. 18 in the bathroom of his luxurious Buenos Aires apartment, a bullet in his right temple. A .22-caliber gun was found next to him.

Did Nisman, 51, commit suicide, as evidence made public so far seems to indicate, or was he killed? If it was a homicide, who committed it and why?

Two-thirds of the Argentine public thinks Nisman was assassinated, with half of those believing the government headed by President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner was somehow responsible, according to a recent Ipsos poll. Fernandez has denied that any coverup occurred. But she also thinks Nisman may have been slain.

Here’s what is known so far:

THE BOMBING:

On July 18, 1994, a van loaded with explosives drove into the Argentine Israelite Mutual Assn. (AMIA) headquarters in a densely populated commercial district of Buenos Aires, killing 85 people and injuring at least 150. It was the deadliest terrorist attack in Argentina’s history, but not the only one. Two years earlier, the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires was bombed, killing 29 and wounding 242. Islamic Jihad, a Lebanese Shiite Muslim group thought to have ties to Iran, claimed responsibility for that attack.

THE BOMBING INVESTIGATION:

Nisman, a federal prosecutor appointed to lead the investigation, filed a criminal complaint in 2006 alleging that Iran and another Lebanese Shiite militia, Hezbollah, were responsible for the AMIA bombing. The motive, the complaint alleged, was Argentina’s decision to stop supplying nuclear materials and technology for Iran’s nuclear program. And though the “driving force” behind the attack was said to be the cultural attache at the Iranian Embassy in Buenos Aires, the orders, according to the complaint, came from top Iranian officials. There was abundant circumstantial evidence: cellphone records, bank transfers, the departure of Iran’s ambassador and deputy chief of mission from Argentina days before the attack. Iran denied involvement and refused to extradite the suspects; the case remains unsolved.

THE DOMESTIC COMPLICATIONS:

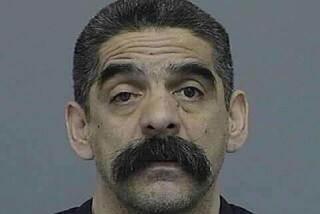

The purported skulduggery wasn’t limited to Iran. Nisman claimed to have found evidence of a coverup at home too. He accused then-President Carlos Menem and several officials in the intelligence and security services of helping hide the tracks of local accomplices of the bombers, including a Syrian Argentine businessman. Menem, the son of Syrian immigrants, is awaiting trial on charges of obstructing the investigation.

And then Nisman began finding coverup fingerprints involving the current government — or so he said. In a report given to a judge five days before he died, the prosecutor alleged that Fernandez had secretly reached a deal to prevent prosecution of the former Iranian officials. He said the deal — which Fernandez contends never happened — may have been made in exchange for favorable trade deals, including an exchange of Argentine grain for Iranian oil. Part of the unsolved mystery is the timing of Nisman’s sudden Jan. 12 return from vacation in Spain to release his report. What information did he get, and from whom?

THE DEATH INVESTIGATION:

The initial autopsy concluded that Nisman had committed suicide. The pistol found near his body had been lent to him by fellow investigator Diego Lagomarsino, who said Nisman asked for it because he didn’t trust his security detail. That no suspicious visitors were reported entering Nisman’s apartment at the time of his death seems to support the idea of suicide. The trajectory of the bullet also is consistent with that theory, as is the presence of Nisman’s fingerprints on the weapon.

But among those with questions is Viviana Fein, the prosecutor heading the investigation. Immediately after the death, she publicly described the case as “suspicious.” Another is Fernandez, who wrote on her Facebook page shortly after Nisman’s death that she was “convinced” that he had not committed suicide. In her lengthy entry, she threw out several possible scenarios, including one in which rogue elements of the government’s Secretariat of Intelligence may have killed him because those who wanted to “use him alive now want to use him dead.” She has since ordered the intelligence agency disbanded.

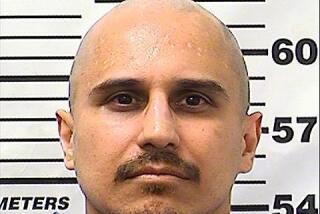

Last week, press attention focused on Antonio “Jaime” Stiuso, the third-highest ranking official in the Intelligence Secretariat, who had been working closely with Nisman in the AMIA investigation. Stiuso was called by Fein to give evidence after phone records indicated he was among the last people to talk to Nisman. The late prosecutor had acknowledged his closeness to Stiuso, saying in one interview that Fernandez’s late husband and predecessor, Nestor Kirchner, introduced him to the intelligence officer, describing him as the most knowledgeable man in Argentina about the AMIA bombing. Stiuso has yet to testify, and his whereabouts was unknown late last week.

Family members and friends dismiss the notion that Nisman killed himself. His ex-wife, federal Judge Sandra Arroyo Salgado, said that before his death she received a mailed photo of him with markings that she regarded as threatening. “This end was not your decision,” she said at his funeral.

Nisman died “trying to shed light in the shadows that were cast over us a long time ago,” friend and philosopher Santiago Kovadloff said.

Special correspondents D’Alessandro reported from Buenos Aires and Kraul from Bogota, Colombia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.