I.M. Pei, acclaimed Chinese American architect, dies at 102

I.M. Pei was fascinated with the geometric swoops and dips of the buildings in Guangzhou, the bustling seaport near Hong Kong, and became enamored with the avant-garde architecture and towering skyscrapers he saw as a youth.

He was equally fascinated with the kings, presidents and autocrats who could bankroll such elegant buildings.

In a career that spanned decades and entire continents, Pei became one of the most distinguished architects of his time, his work on public display from Paris to West Los Angeles.

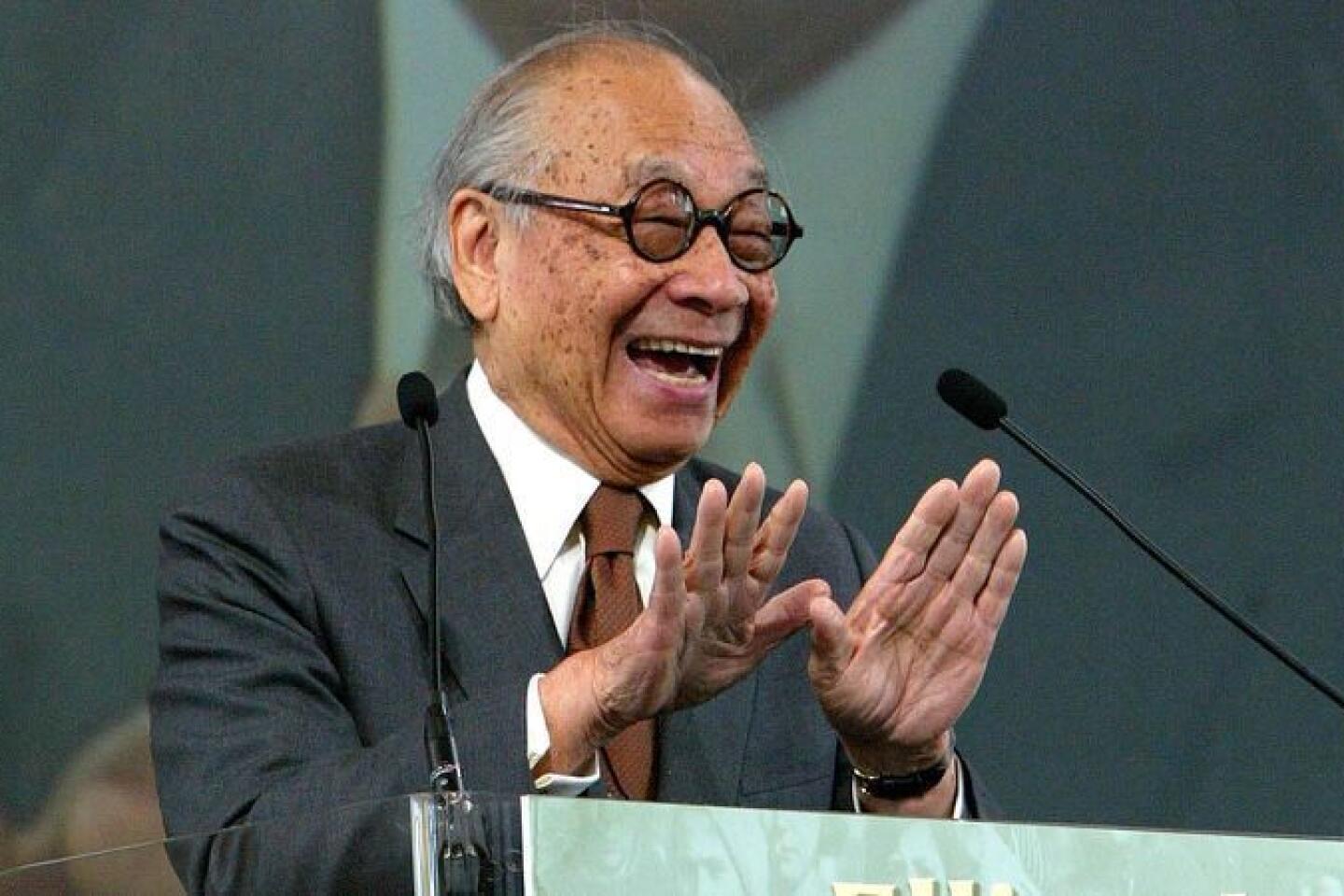

Pei, out of the public eye for much of the last decade, has died at the age of 102, his sons’ architecture firm announced Thursday. Further details were not available.

Pei, who won the coveted Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1983, had a client list that was a who’s who of 20th century notables, including French President Francois Mitterrand for the Louvre, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis for the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library in Boston, and art collector and philanthropist Paul Mellon for the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

As the head of a prestigious architectural firm based in New York City, Pei oversaw dozens of well-known projects, including the now widely admired 60-story John Hancock Tower in Boston designed by partner Henry N. Cobb, a project that initially threatened to ruin the firm when its windows began popping out and crashing to the ground.

Pei’s projects, though sharing in some way his love of geometric forms, were varied in style but not on the cutting edge. He said he liked to compare his approach to architecture to the music of Bach — “constant variations of a simple theme.”

“I am not an architect who has a body of theories,” he said in “First Person Singular,” Peter Rosen’s 1997 documentary on Pei. “I don’t think that’s how my architecture should be looked at.

“But if you are true to yourself, you have a signature, and the signature will come out.”

Pei’s virtually unmatched ability to move his and his firm’s designs off the drawing board and onto construction sites was due to the superiority of their designs. But, as the scion of a prominent banking family in China, he also had the elegant bearing and cultural refinement that enabled him to move comfortably in the milieu of the clients who could afford his projects.

“He knew who he was. He knew he had had an important career. He was proud of his work,” UCLA architecture and history professor Thomas Hines said. “On the other hand, he didn’t have that overriding ego that so many architects of his stature have had.”

But Pei also could be steely, insisting that things be done a certain way on his projects.

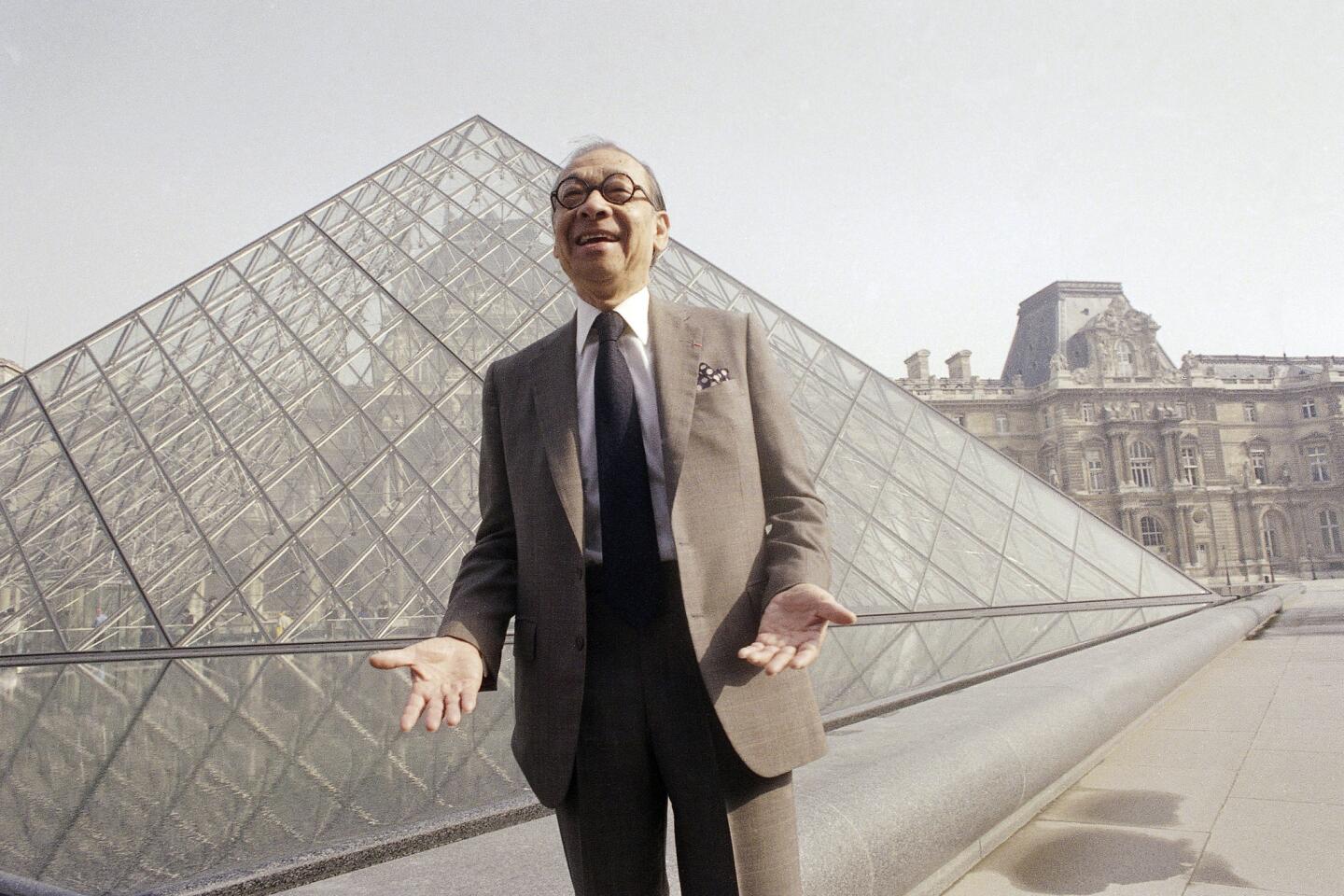

His determination to see a project through to what he thought it should and must be was perhaps most sorely tested at the Louvre, a project he reluctantly accepted.

But Mitterrand insisted, believing that Pei was the best one to devise a plan to build a new entrance and also improve the complex of buildings that over the centuries had been transformed from fortress into public museum.

Before taking on the project, Pei secretly visited the Louvre several times, finding it in “pitiful” condition — disorganized, dreary and with services that were barely functional. Pei told Timothy W. Ryback of ARTnews in 1995 that he came away in a fever to do something for the museum that housed “the greatest collection I know.”

Because there was a danger in digging under the Louvre itself, the obvious place to install a new entrance was beneath the Napoleon Court, an open area between the two wings.

But what should the structure be? Pei did not think the entrance should simply be a sunken hole because “the Louvre needs something prestigious.” But should a surface structure match in some way the other parts of the Louvre? Or be a counterpoint to them?

Pei chose a pyramid, which because of its structural stability could be built to be transparent and light.

He quickly realized that the beauty of this solution might not be as readily apparent to the French — that they might, as he told ARTnews, “raise holy hell” about such a radical plan for their beloved museum. Still, even he was taken aback by the intensity of the criticism.

In January 1984, when he presented the design to the Monuments Historiques, a commission of architects, curators and conservators, the criticism was vicious.

The French media followed with similar reaction. Le Figaro called the design “soulless, cold and absurd” — in short, “inadmissible.” Le Monde called it an “annex to Disneyland.”

But Mitterrand did not waver. Construction of the pyramid proceeded, and when it opened in 1988, it was not only Mitterrand who declared it “a thing of beauty that will be inscribed forever in our history.” In a remarkable turnaround, the French public overwhelmingly embraced it. Pei, to his astonishment, was a virtual national hero.

“I consider the Grand Louvre the greatest challenge and the greatest accomplishment of my career,” Pei told ARTnews.

Ieoh Ming Pei — his first names mean “to inscribe brightly” and his last name is pronounced “pay” — was born in Guangzhou, China, on April 26, 1917, to a family with deep roots in Suzhou, a city northwest of Shanghai known for its craftsmen, artists and scholars. His father was a successful banker who moved the family to Hong Kong and then Shanghai; his mother, who died when Pei was 13, was proficient at calligraphy, poetry and music.

As a teenager, Pei was fascinated by the construction in Shanghai of a multi-story hotel and told his father he wanted to study architecture.

Pei left China in 1935 for the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Within weeks, fearing he could not execute the drawings he thought necessary for architecture, he moved on to MIT to study engineering. He later switched back to architecture at MIT, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1940.

During his studies, Pei admired Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright. Like so many architects of the 20th century, Pei also was deeply influenced by Le Corbusier, later telling Rosen in “First Person Singular” that he took from the Swiss-born Modernist French architect a sense of freedom and “plasticity of forms” as well as an appreciation for how one’s work should relate to one’s time.

Pei had intended to return to China to practice architecture, but war and revolution delayed him. He took a job in a Boston engineering firm; married Eileen Loo, a Wellesley student; and enrolled at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

During World War II he volunteered at the National Defense Research Committee in Princeton, N.J., and afterward returned to Harvard, where he earned his master’s degree and also taught.

Harvard at the time was a treasure house of mentors for architecture and design. Walter Gropius, the “form follows function” founder of the Bauhaus architectural school in Germany, was chairman of the Graduate School of Design.

But Pei did not always agree with the direction of thought at Harvard. To prove that there was a limit to an “international style” that Gropius propounded, Pei came up with a design for a Shanghai art museum that incorporated traditional Chinese architectural characteristics — a bare wall and small individual garden patios. Gropius praised the design for illustrating “that an able designer can very well hold on to basic traditional features without sacrificing a progressive conception of design.”

In 1948 Pei was lured away from Harvard by William Zeckendorf, the rough-and-tumble real estate tycoon who was already famous for assembling the land for the United Nations building in New York City.

Zeckendorf’s firm, Webb & Knapp, oversaw massive postwar urban renewal projects around the country. Pei eventually headed a team of 75 architects. While still at the firm, he established I.M. Pei & Associates and five years later struck out on his own. The firm eventually became Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, from which Pei retired in 1991, although he continued to design afterward.

One of the Pei firm’s initial major projects was the research complex at the National Center for Atmospheric Research outside Boulder, Colo. Built in the 1960s, it was, Pei said, the first time he was totally involved with the design process rather than overseeing others’ work. He slept in a sleeping bag on the site to experience the elements and soaked up inspiration from the Indian cliff dwellings at nearby Mesa Verde.

While the facility was under construction, Pei won the commission for the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston. Being chosen by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the widow of the president who had been assassinated in 1963, was a coup for Pei. But the library would be fraught with problems, going through several designs for several different sites over a decade.

It finally was dedicated Oct. 20, 1979 — more than 14 years after Pei got the commission — and Pei did not disguise his disappointment with how it turned out. Yet despite its failures, he would come to believe that the JFK library was the turning point for his firm, opening the world to more important commissions.

At the same time that the library was on its rocky path to completion, however, the firm faced its greatest challenge at the sleek Cobb-designed John Hancock Tower in Boston.

As the 60-story building neared completion in 1972, an architect’s nightmare occurred: Huge windows weighing 500 pounds crashed to the ground. More cracked or shattered in a subsequent storm. Although no one was injured, plywood took the place of many of the windows. More than 10,000 windows were replaced by the time the building was completed in 1976.

But on other fronts, good things were happening.

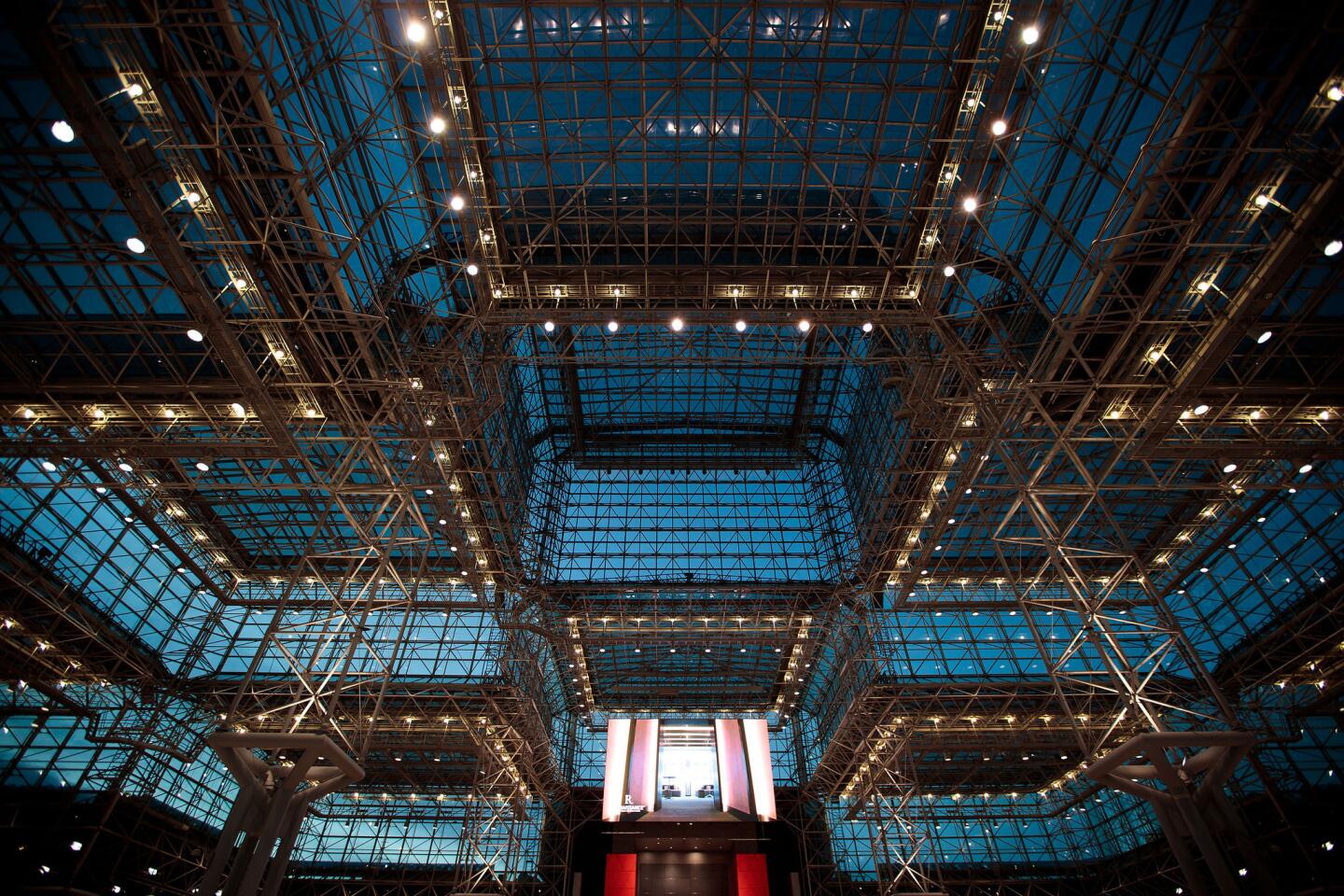

In 1968, two years after Pei’s firm had started the Hancock Tower project, Pei was chosen over such icons as Louis Kahn and Philip Johnson to build a project that would in the end redeem the firm: the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The site in the nation’s capital, adjacent to the original neo-Classical National Gallery that had opened in 1941, was difficult: It was shaped like a trapezoid — a rectangle in which only two sides are parallel.

In a creative process that Pei often recounted afterward, he did a rough sketch slashing the trapezoid diagonally in half, forming two triangles. One triangle would become gallery space divided into smaller rooms; the other would be a more scholarly study center as well as offices.

The interior would gain excitement and grandeur by the installation of a monumental Alexander Calder mobile that hovers overhead in the central space. And, finally, the exterior design lent itself to the now-famous “knife edge” where two outside walls meet — an edge so fascinating to visitors that in the ensuing years it has been worn smooth by human touch.

When at last the East Building opened in 1978, Washington Post architectural critic Wolf Von Eckardt raved that it was “I.M. Pei’s architectural hallelujah.” Architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable allowed that while “it does not break ground,” it did deal in “established excellence.”

Although politics forced Pei to give up on his dream to return to China to live and work — he became a U.S. citizen in 1954 — he finally got a chance in 1979 to design a project in his home country: the low-slung, zig-zagging Fragrant Hill Hotel near Beijing. Other chances would come later to build in China, including a museum in Suzhou, the home of his ancestors, that was completed in 2006. He also designed the exquisite Miho Museum near Kyoto, Japan, which opened in 1997.

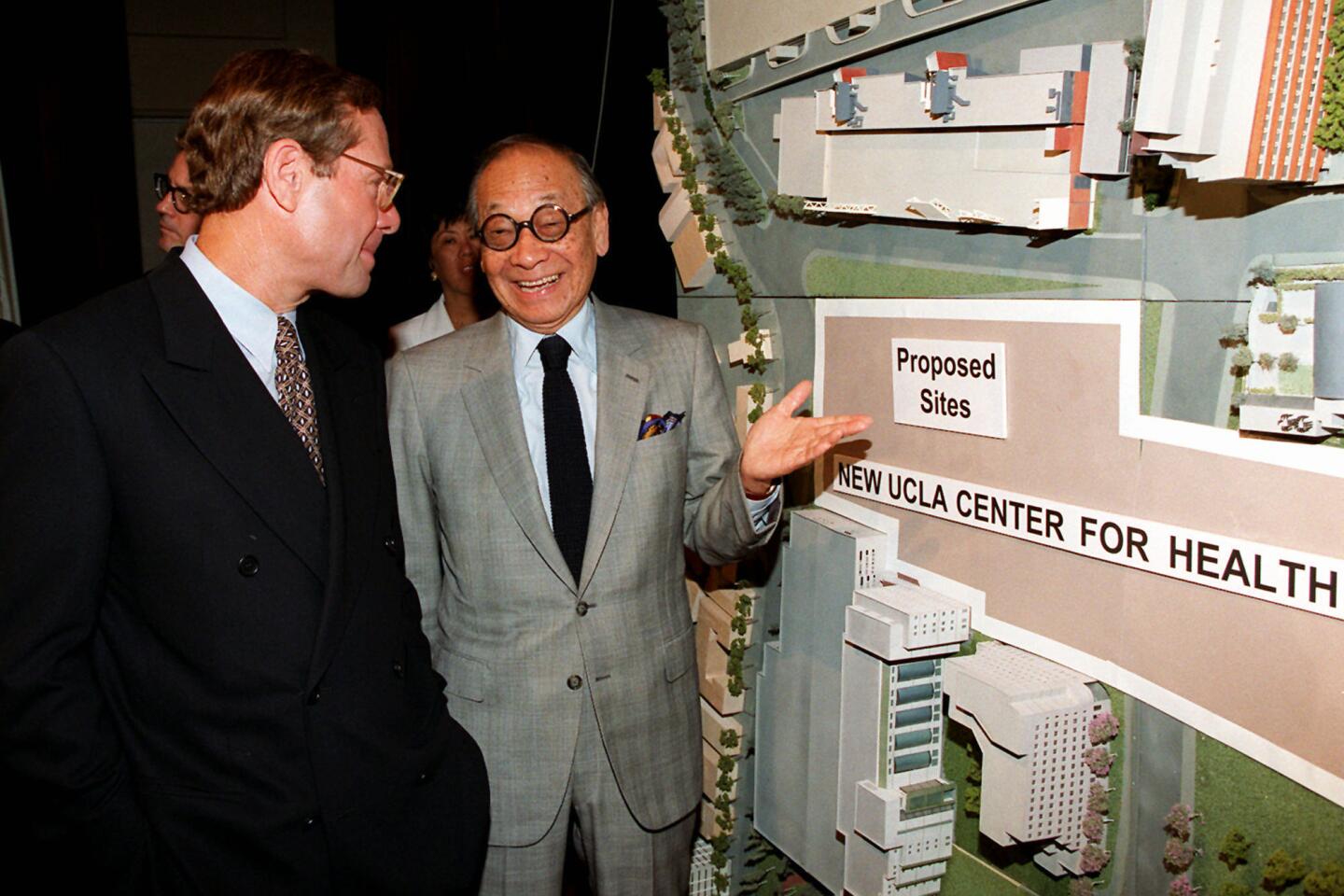

One of Pei’s last major projects in the United States was the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland, completed in 1995. Among several Pei projects in the Los Angeles area are the former Creative Artists Agency headquarters in Beverly Hills and the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center.

His last major work was the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, in 2008.

Pei’s wife, Eileen, died in 2014, and a son, T’ing Chung, died in 2003. He is survived by two sons, Chien Chung Pei and Li Chung Pei, and a daughter, Liane.

Luther is a former Times staff writer.

Staff writers Cristie D’Zurilla and Steve Marble contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.