The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In the new Phaidon book “Concrete Architecture,” Los Angeles writers Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin examine a construction material that’s often derided as the building block of urban eyesores, but, they argue, also can be the foundation for uncommonly expressive design.

“Concrete has seduced architects and engineers,” they write, “to prove it can produce works complex and simple, graceful and awkward, delicate and overbearing, mischievous and sinister, gravity-defying and earthbound.”

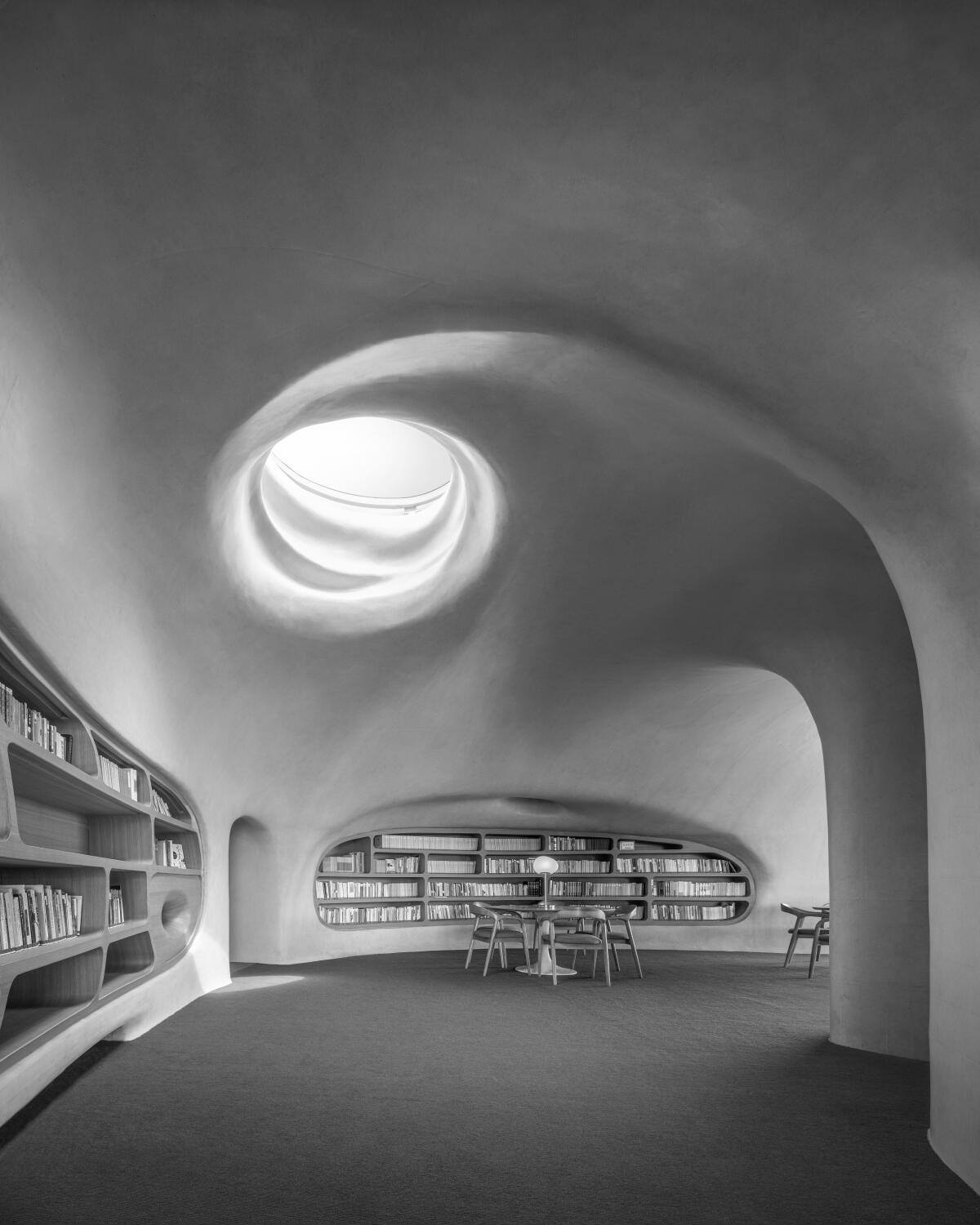

Chronicling more than 300 private homes and public spaces built from 1913 to 2022 — in styles including Bauhaus modernism, Art Deco, Cold War-era brutalism and postmodern “blobitecture” — the book is illustrated with dramatic black and white photography that “allows the material to shine through, with no distractions,” Goldin writes.

The authors focus on the ingenuity of designs, whether built as monolithic slabs for churches, sculpted as war memorials or shaped into domes and arches for museums, apartment houses and parking structures. The finished structures are reminiscent of origami constructions, Jenga stacks, pyramids, igloos, boats, submarines and alien spacecraft. Other examples illustrate how concrete can be cast into decorative elements (such as the X-shaped grilles on the American Cement Building near L.A.’s MacArthur Park) and complex curves (a la Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York City) that resemble mollusks, nautilus shells, honeycombs and volcanoes.

Global in its scope, with buildings from more than 60 countries, “Concrete Architecture” also celebrates the local, highlighting 10 Southern California landmarks, including the 1970 Geisel Library at UC San Diego, the 1965 Salk Institute in La Jolla, Wright’s 1924 concrete textile block Ennis House in Los Feliz and the 2015 Broad museum in downtown L.A. Here are some of the awe-inspiring structures featured in the book.

Made from béton brut (concrete that is unfinished after being cast, showing the marks of the mold), this 1970 memorial in Belgrade honors men from regions of the former Yugoslavia who gave their lives fighting German and Italian forces in World War II. The star-shaped monument, the authors observe, “can also be read as five identical abstract figures standing back-to-back, as if in a last stand, rifles pointing outwards, individuals yet unified.”

Built in Villanueva de Cordoba, Spain, this 2013 design serves as a covered viewing deck in a grove of protected holm oaks. Made from 20-foot-square intersecting concrete vaults, the structure takes inspiration from cloister architecture and the canopies of trees in the area.

This 11-story tower, built in Cordoba, Argentina, in 2012, “is like an origami lantern made of concrete,” the authors write.

“One of concrete’s unique characteristics is its ability to be shaped into formlessness, divorcing it from familiar associations,” the authors say of this 2020 pavilion built in the seaside port of Haikou, China.

This 2019 place of worship in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, was designed by the Danish architectural firm Cebra. “This concrete landscape appears to grow and shrink, consisting of both horizontal and sloping surfaces — some as small as a stool,” the authors write.

Designed by Austrian architect Werner Tscholl and cantilevered over a steep Alpine ridge, this 2010 building commemorated the completion of a challenging mountain road in 1960. The structure was conceived, the authors write, “in harmony with the natural rocky landscape.”

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.