Cost overruns, delays, now coronavirus. Academy Museum chief Bill Kramer isn’t fazed

The back story has been dramatic. The narrative, circuitous and complex. But the new Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is, even in the age of coronavirus, readying for its big premiere.

The $482-million Renzo Piano-designed museum — in the works for decades and burdened by construction delays and cost overruns, divergent visions, in-fighting and leadership changes — still plans to open its doors to the public Dec. 14, a date that two-time Oscar winner (and COVID-19 patient) Tom Hanks announced onstage during this year’s Academy Awards telecast.

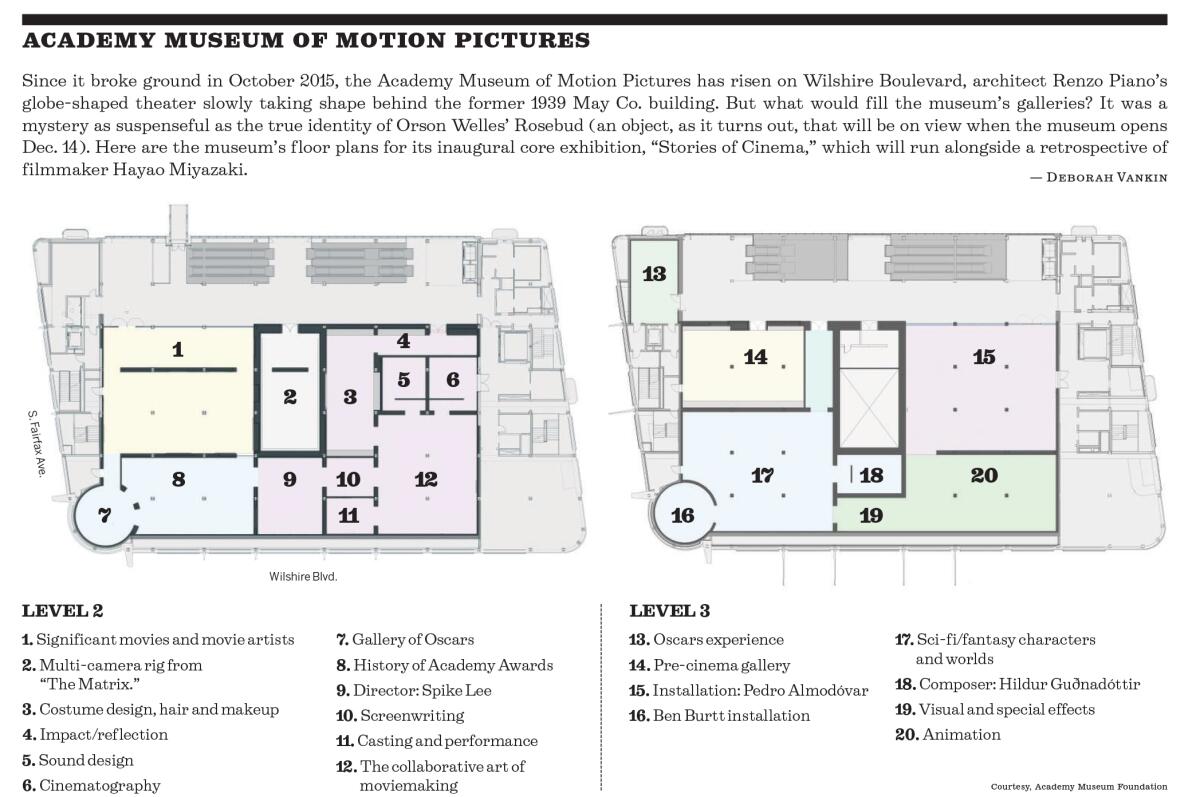

The museum said it is reassessing that construction time line after it halted the final stages of construction the day before Gov. Gavin Newsom issued his safer-at-home order. In the meantime, for prospective visitors looking ahead toward when this monument to movie history and culture does finally open, a chief question remains: What exactly will they see inside the galleries?

Director Bill Kramer, who took over former director Kerry Brougher’s post in January, sat down with The Times to offer a preview, sharing exhibition blueprints and candidly discussing ballooning construction costs in this edited conversation, which initially took place in late February and has been updated where noted.

Why Dec. 14 as the museum’s opening date?

We just made a timeline. The schedule took us to November for final installation. That gives us time to test, refine the lighting, do all of the final touches. But also, we’ll hit post-Thanksgiving, the tourist rush that comes into L.A., interest in the Oscars, end-of-the-year films being released. There’s a lot of excitement at that moment, and we’ll capitalize on that. [In a recent interview Kramer added, “Of course we’re continuously working with our construction teams and exhibition fabricators, and monitoring our time lines, as the coronavirus crisis plays out.”]

The project, which includes Piano’s giant concrete spherical theater building, is about $100 million over budget. It was $388 million, and now it’s $482 million. Why?

It’s a combination of several things that happened over the last four years. The sphere is a complicated structure; we’re restoring a 1939 building, and there were a lot of complex components that we wanted to get right. And we decided to combine two smaller theaters and create a larger theater — the 288-seat Ted Mann Theater — and the movement of that theater to the lower level created some additional expense.

But we’re almost done with our first fundraising campaign, our $388 million campaign. We’re at 96%. We will immediately launch a second campaign to raise the additional capital funding that we need, to cover that additional cost as well as new endowment and programming and operating money. Once we’re open, we’ll have a whole new set of stakeholders coming to the museum. So if we have 800,000 visitors a year, those are new potential donors to the project.

The Oscar telecast is four-fifths of the academy’s annual revenue. Given the recent show’s ratings — the lowest in Oscar history — are you worried about support for the museum’s programs?

We have great hope for the future of the show. The Oscars has a contract through 2028. The museum itself will have many sources of revenue: ticket sales, the cafe, our retail store, rentals [of theaters], our fundraising campaign. Our goal, long-term, is to have our annual operating budget be almost entirely funded in that way. The plan is for the academy to help us as we ramp up and build our endowment. For our annual operating budget, the long-term goal is to be self-sufficient.

You were the museum’s chief fundraiser from 2012 to 2016 before leaving for the Rhode Island School of Design and then the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Why did you return — and is L.A. now a harder city in which to raise money?

I’ve always believed deeply in the importance of the Academy Museum and have always loved L.A. I’m thrilled to be back; it’s a different city. It’s grown, it feels more international, there are many more big projects happening. Because our project seems more real to people — the building is here, we have strong exhibition plans — we’re finding the response to our campaign to be fantastic. Especially over the last four or five months. So it’s not a harder city to fundraise in. There’s more excitement.

You hired wHY Architecture’s Kulapat Yantrasast and Brian Butterfield to design the gallery interiors, and you’ve reimagined the museum’s core exhibition. How has it changed?

We wanted to move away from a chronological march through film history and build something that is more dynamic, surprising, diverse and engaging. Our core exhibition is being designed in such a way that stories can change over time. So we’ll be able to swap out vignettes on movie artists and movies, create a new room on the art of moviemaking around a different movie, add to the Academy Awards history galley, move costumes in and out because we want to tell a lot of diverse stories over time. Every eight to 12 months, 20% of this will shift. So you’re constantly seeing new things as you come back.

It’s important to note that it’s called “Stories of Cinema.” There’s many stories of cinema. There’s not one history of film. Many voices, many movie artists, many narratives. And in all these areas we’re celebrating the history of the movies, but we’re also talking about complicated stories.

Such as?

Hattie McDaniel winning in 1940 for “Gone With the Wind.” She was best supporting actress, but she had to sit in the back of the ceremony because it was a segregated area. We want to face that head on. We want that here.

The museum has grown its permanent collection from 3,500 objects in December 2018 to 5,000. Is it still acquiring? And what object thrills you the most?

We’re constantly acquiring; we’re constantly getting donations. It’s not always us going to auction and buying. In the last month alone, we acquired several costumes worn by Hugh Jackman in “The Greatest Showman,” “Logan” and “X-Men.” We also acquired a Vid-Phon and booth from “Blade Runner,” two title cards from “Young Frankenstein” and a gown from “Adam’s Rib” worn by Katharine Hepburn. The object that excites me the most is [H.R.] Giger’s “Alien” head. It is such a beautiful piece of design, so strong and evocative, and you’re immediately thrown into the movie.

You enlisted filmmakers to serve as curators. Who’s participating and what will we see?

There’s a room where we’ll turn it over to a director to talk about the craft. Spike Lee’s doing the first one. Spike has his own collection of items from his films and other movies that have influenced him over time: objects, costumes, scripts, posters, props. He’s giving us his Kobe-inspired outfit.

We’re creating an original installation with Pedro Almodóvar that will reference his films and influences in a space that’s floor to ceiling sound and projection, no text. An immersive experience.

We’re turning [a gallery] over to Hildur Guðnadóttir, the Icelandic composer who won this year for “Joker.” In the Inventing Worlds & Characters section, sound designer Ben Burtt is creating an outer space montage film in the cylinder [gallery].

Will any of the exhibits be interactive?

Yes. A great example is in our double-height Hurd Gallery, where we’ll install the original multicamera rig and system used to create the 360-degree, slow-motion, rapid-fire image capture made famous by “The Matrix.”

How earthquake-proof is the glass dome over the Sphere Building’s terrace?

It’s completely earthquake proof, the whole space. Because the Sphere Building’s base isolators absorb seismic activity from the ground rather than transmitting energy upwards, the glass dome on the Dolby Family Terrace experiences much less shaking during an earthquake than a typical building.

Did the building structure complicate or extend the city’s permitting process?

No additional permits. We had to meet building and safety code, which we did. I think the biggest challenge that we solved with that space was heating and cooling. We have a radiant heat and cooling floor but we’ve also left openings on either side, so there’s a beautiful cross breeze. And we also have a system of shades.

We were inventing a new space, so we definitely had to prove what we were doing was up to code. And there were many iterations to get us there to achieve aesthetically and functionally what we wanted. But Renzo is known for creating dynamic new spaces that are also very human, and I think that space achieves that. And with Gensler [the executive architecture firm] helping with code, it was less complicated to get the design approved than one would think.

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art is beefing up its film offerings. It recently acquired a robust archive documenting African American cinema history. Are you concerned about duplication?

These are all diverse, important discussions. I think there’s plenty of room for everyone. We plan on borrowing pieces, we plan on loaning pieces from our collection to them. The Lucas Museum is so much more than just film. It’s a museum of narrative art; it’ll be much more than just movies. We plan to work with them closely.

How do you make a museum of film objects and history relevant to a younger audience raised on streaming and watching movies on their iPads?

There’s a lot of current films that young people will recognize that will pull them into the conversations around film history. A lot of using current cinema to reflect historical cinema.

Does a movie museum matter as much now as it might have a decade ago?

I think it’s always relevant. People continue to watch movies in a variety of formats, whether it’s a classic film or the latest Marvel film. Of course the industry is changing. Ted Sarandos [Netflix’s chief content officer] is on our board. He’s part of that conversation. Last year’s “Marriage Story” and “The Irishman” [both Netflix releases], those are still movies and movies that we’ll talk about in the museum. I think it just expands the conversation. It’s our role to show audiences, who may not be going into theaters to see movies, that this is all linked; the movies you’re enjoying at home streaming are connected to classic films.

The academy doesn’t promote Oscar nominees during awards campaigning because it would appear to be favoritism. But the Academy Museum will have filmmakers inevitably participating in programming, so how will the museum avoid favoritism during awards season?

There’s a church-state divide. Every studio has made a gift, but the decisions we make in terms of curatorial content and programming are completely separate from any campaigning discussions or the desires of a donor.

There will be programs tied to the work of our academy members and branches. You’ll see the work of all of our branches in all of our galleries. And there may be content that later in the year connects to someone who may be campaigning for another film. But we keep those separate. We want to be very careful. So we’re not showing first-run films; we’re not screening Oscar-nominated films before the Oscars.

Over the years, the museum has endured opposing visions and in-fighting. Is everyone on the same page now about what the museum should be?

Absolutely. In December we presented our exhibition and programming plans to the academy board, the museum board, the academy foundation board, our inclusion advisory committee, and we had a universally positive response. We wanted to make sure our internal stakeholders, our academy members represented by those groups, felt connected to our vision and on board with that vision. I feel like whatever was happening before, we’ve gotten over that hump.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art stirs some controversy as construction continues amid coronavirus.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.