How Kulapat Yantrasast, the architect behind the Marciano Art Foundation, is bringing a bold openness to museum design

The Scottish Rite Masonic Temple in Los Angeles has led a life that is beyond extraordinary.

The epic, travertine structure on Wilshire Boulevard began its existence as a “cathedral” for the Freemasons in 1961, a stage for the elaborate costume rituals of the secretive fraternal organization. By the 1990s, when Freemasonry had lost its appeal, the building was reborn as a center for police funerals and as a barracks for National Guard troops deployed during the Los Angeles riots.

Later, it was home to boxing matches and raves. Hollywood has also stopped in, employing the building as a set for the 2004 action flick “National Treasure” starring Nicolas Cage.

This history is something that architect Kulapat Yantrasast was intent on preserving in his redesign of the space — which has transformed the vast Wilshire Boulevard structure (long thought to be a real estate white elephant) into Los Angeles’ newest museum: the Marciano Art Foundation, which is set to open its doors Thursday.

“I like it because it feels like it’s alive,” says Yantrasast, as he walks through empty galleries on a blustery March afternoon, the smell of paint hanging heavily in the air. “It’s not a white box. It has these eccentric details.”

The details include elaborate mosaics created by artist and designer Millard Sheets, the building’s original architect. There are stained-glass windows framing two-headed eagles — a symbol of the Freemasons. And an enormous ground-floor hall reveals its past as a 2,000-person theater, the imprint of an old balcony seating area visible against a rough concrete wall.

“The space is finished,” says Yantrasast, gesturing at the wall. “But I wanted to leave the ghost of the balcony steps there, of what it once was.”

Yantrasast’s careful devotion to coaxing the past lives out of this building — rather than gutting it until nothing remained but a shell — is exactly why Maurice Marciano, the blue jeans mogul and art collector who established the Marciano Art Foundation, wanted the architect for the job.

“Any reuse project is a challenge for an architect because you’re dealing with existing structures,” says foundation deputy director Jamie Manné. “The way he kept the large fixtures, the marble, the gold ceramic tiles — it’s respecting the history of the building.”

And he did it without sacrificing the principal architectural mission, which is to display the foundation’s collection to great effect.

“I almost cried the first time we put up a piece of art,” says Manné. “The sightlines he has created are nothing short of unbelievable. Everything is so beautiful and thought out.

“He is a great editor. He’s got restraint.”

Yantrasast — the Thai-born, Japan-educated, L.A.-based founder of the Culver City firm Why — is increasingly sought after in the cultural sphere for his ability to skillfully conjure environments that suit the needs of art.

In 2014, he completed a studio art building at Pomona College — a Tetris-like arrangement of airy concrete boxes that surround an open-air courtyard sheltered by a gently undulating roof. (A welcome visual break from the campus’ red tile look.)

Two years later, he completed a renovation and expansion of the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Ky., a redesign that tripled that institution’s gallery space — and made sense of a pile-up additions that had accumulated over the years. And last month, he unveiled a new showroom for Christie’s auction house in Beverly Hills that features flexible exhibition spaces and a sleek staircase wrapped in a gently curving wall.

“He really understands that for art, it has to be very minimal,” says Sonya Roth, the managing director of Christie’s Western region, “but he knows how to make that special.”

And that’s just the buildings. His firm, which has a staff of roughly three dozen, also has a thriving museum installation design practice.

In 2015, for example, he created the searing installation for an exhibition of samurai armor at the

“Because of his background in Japan, he knew the two extremes,” says Robert T. Singer, the curator of the exhibition and head of LACMA’s department of Japanese art. “He had the kabuki, the over-the-top, but he also knows the tea ceremony, the wabi-sabi side. He hit you in the face when you came in, but there was a lot of subtlety there too.”

Yantrasast, who at any given moment is juggling numerous design and construction projects — not to mention a rigorous travel schedule (he also maintains an office in New York) — says he enjoys the museum work.

“You can’t crank out a building,” he says. “The pace is so slow. That’s why I seek out these small projects. These often lose money, but they give us a break. They can be very creative.”

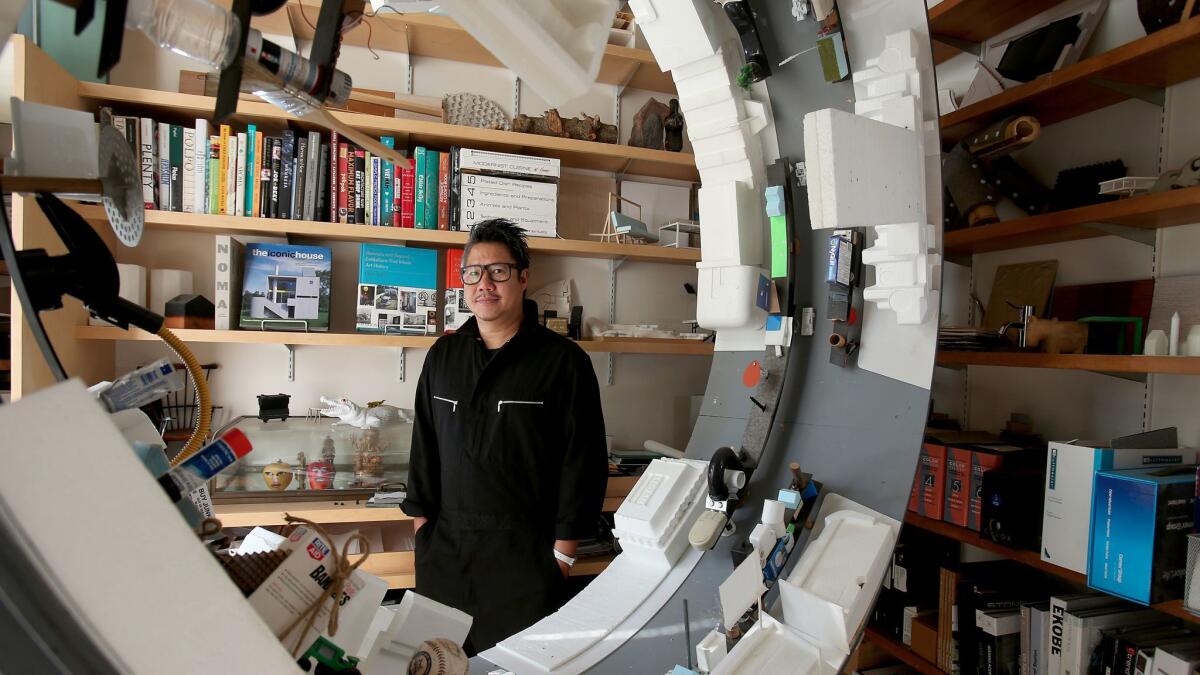

On the surface, Yantrasast might appear to fit right in with central casting’s idea of an architect. There is the stylish eyewear and the shock of black hair streaked with white. On the day that we meet he is decked out in chic black Japanese overalls and Nike sneakers with an artful gray fade.

Yet he is far from the archetypal chilly designer with an uncompromising vision (à la Howard Roark in “The Fountainhead”).

Yantrasast is funny and warm, as intrigued by vernacular culture as he is by high art. During the course of an afternoon interview, he expresses admiration for the choreographies of Pina Bausch and the sculptures of artist Gabriel Orozco. He also stops to admire homegrown modifications on a jalopy Toyota.

I see my job as pushing people to speak out and wait to observe the sparks.

— Kulapat Yantrasast, architect

To outline his firm’s design philosophies he doesn’t have slick, digital renderings. Instead, he distributes a small zine full of whimsical drawings.

The first concept addressed? Collaboration.

“I see my job as pushing people to speak out and wait to observe the sparks,” he says of his design process. “Someone will say, ‘That’s a good idea.’ So, you talk more about that.”

This openness is something he attributes partly to his Thai upbringing.

“I want things to happen,” he says. “I don’t want to control.”

Yantrasast was born and raised in Bangkok, the son of an electrical engineer and a schoolteacher. Neither was a die-hard art aficionado, but culture was important to the family.

“They would take us to Europe,” Yantrasast says. “We’d stay at the cheap hotel next to the train station, but we’d go see museums. For me, what was amazing was going to a city like Paris and thinking, ‘Someone made this. This is something I could do.’”

He completed his undergraduate studies in Thailand, then studied architecture at the University of Tokyo.

On a return to trip Thailand, he met Tadao Ando, the Japanese architect who would ultimately win the Pritzker Prize for his graceful yet muscular buildings that offer masterful plays between light and brut concrete.

The encounter was fateful.

In 1996, Ando invited Yantrasast to work in his Osaka studio for the summer — a seasonal gig that quickly morphed into a full-time job.

“[Ando] said to me, ‘Don’t bother getting an apartment, you can stay in our guest room,’” recalls Yantrasast with a smile. “I ended up staying eight years. I would have dinner with them every night. They didn’t have children, so they practically adopted me.”

In Ando’s office, Yantrasast worked on several key international projects — including the firm’s design for the Modern Art Museum in Fort Worth and an expansion project for the Clark in Massachusetts.

Those jobs provided key lessons in materials, client relations and creating containers for art. “I learned discipline,” says Yantrasast. “I learned so much.”

But by 2003 he was ready to break out on his own — and that’s when he moved to California.

Part of the reason was to get out from under Ando’s shadow. (“In Japan, people say, ‘Nothing grows under the big tree,’” he explains.) Part of it was because he was intrigued by Los Angeles.

“I wanted a place with a sense of possibility,” he says. “To be in New York — I didn’t want to be a slave to the city. I’d be doing apartment interiors. I liked this openness.”

Openness suits Yantrasast well.

One of his earliest commissions out of the gate was a museum: a 125,000-square-foot building for Michigan’s Grand Rapids Art Museum, which was relocating from an old federal building on the periphery of the city to a new location downtown. For that project, Yantrasast delivered a modern, classically proportioned concrete structure that beckoned the revitalized city with a grand canopy.

At first, the architect says he was concerned about making a museum out of brut concrete. “I didn’t want people to feel I was Ando-light,” he says.

But concrete was economical and environmentally sound (a requirement of the client) and the structure was well-received. When it debuted in 2007, Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin described it as “a temple of community, not a temple of authority — porous and inviting rather than impervious and intimidating.”

Dana Friis-Hansen, who serves as director and chief executive of the museum, says the building and its functions have held up over time. Flexible design allows the lobby to be used as an event space. A strategically placed atrium draws daylight into various corners of the building. In the galleries, architecture doesn't overshadow the art.

“He is an art-loving architect,” Friis-Hansen says. “He is also a curator’s architect. The galleries areas flow organically. We can add walls, we can subtract walls.”

And there is his respect of the urban life that surrounds the structure.

A glass wall on the building’s eastern facade, for example, connects the building with the street. “Some museums say, ‘You are here and we are going to keep you here at all times,’” says Friis-Hansen. “This allows a mental refresh.… It reminds you of a connectedness to something bigger than just the art museum.”

The Grand Rapids Art Museum catapulted Yantrasast to myriad other cultural projects. Why has worked on gallery design at the Art Institute of Chicago and helped overhaul the interior spaces at the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, Mass.

Currently, he’s refurbishing a warehouse space for the new Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (formerly the Santa Monica Museum of Art) in downtown Los Angeles and he’s working on a renovation and expansion for the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. The firm was also just shortlisted for a prestigious project at the site of Edinburgh Castle in Scotland, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

In the midst of this, the architect is wrapping up the Marciano, where he has brought a dollop of his trademark openness to a building long closed off from public view. But he has done it in a way that is subdued and deferential.

The architecture of a museum doesn’t always need to shout its presence, he says.

“You’re a host,” Yantrasast says genially. “You are not there to say, ‘Look at me! Look at me!’

“My job is just to set the scene.”

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

L.A.'s Marciano art museum will debut May 25. But first: A sneak peek

Design for Obama library and museum off to surprisingly somber start

Compelling case for gray at Pomona College's Studio Art Hall

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.