Behind the story: Learning the truth about director Milos Forman’s escape from Czechoslovakia

My interest in writing about Ivan Passer and Milos Forman’s escape from Czechoslovakia goes back more than 25 years, since almost the beginning of my acquaintance with Passer.

I met him when he was a professor at the USC School of Cinema-Television, which I attended as a grad student in the early 1990s. As someone of Czech heritage who has lived and worked as a journalist in Prague and writes occasionally about film, I took particular interest as Passer held forth with his marvelous stories. I was especially intrigued by the defection story, which had barely been written about.

I envisioned interviewing Passer and Forman together to reconstruct the narrative about how they left Czechoslovakia during Soviet occupation. But I never mentioned my idea more than casually to Passer, as I knew that — unlike any other movie person you’re likely to meet — he detests the spotlight. He avoids media attention when possible — and when not, he accedes grudgingly.

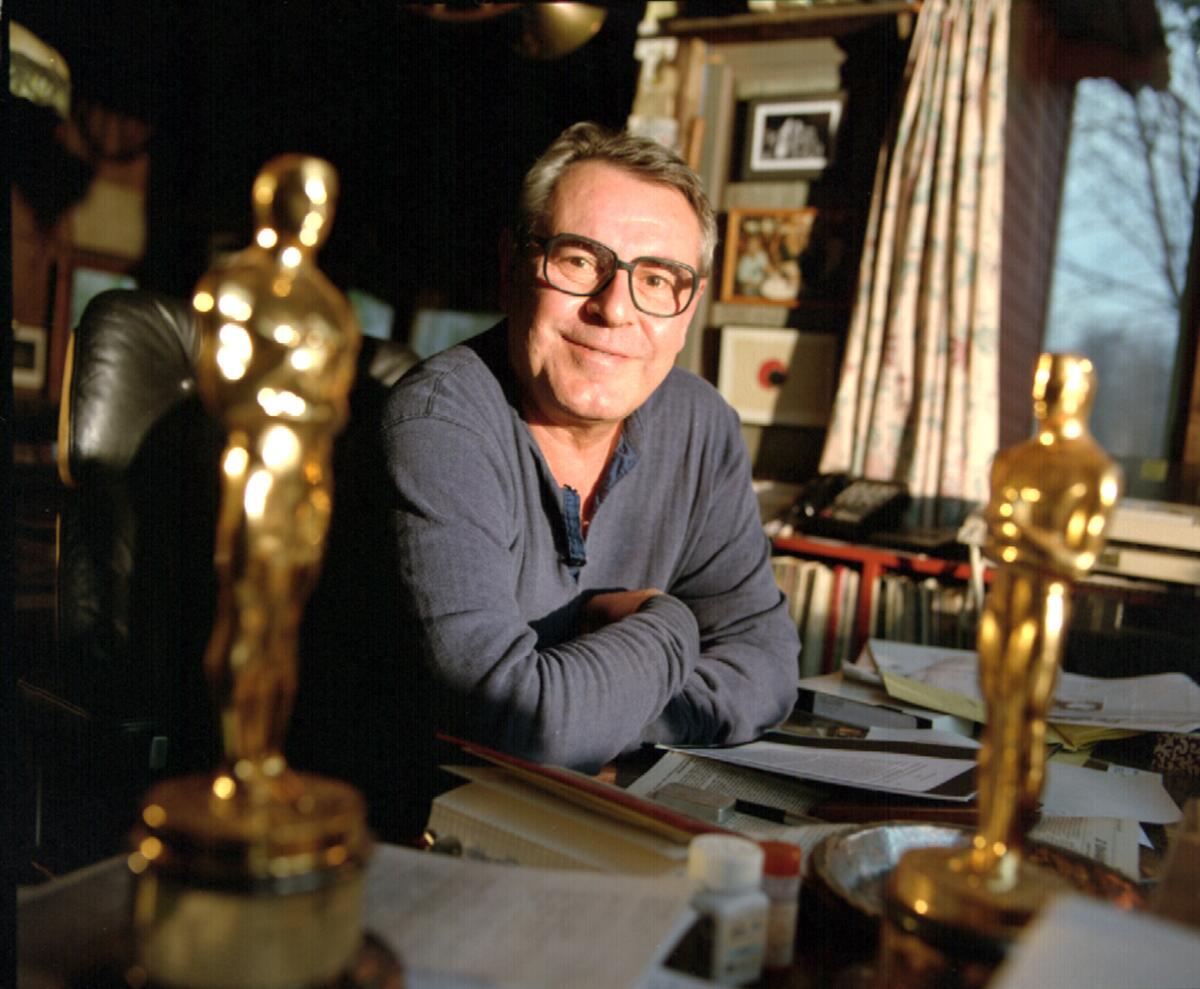

The friendship between Czech New Wave pioneers Milos Forman and Ivan Passer was crucial in the life of the man who directed ‘Amadeus’ and ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.’

Forman’s death last year refocused my attention on the subject, and I finally told Passer my story idea. He agreed — reluctantly, of course. (As I write this, Passer is still advising me that, should I decide not to publish anything after all, “it’s perfectly all right with me — I will be happy.”)

Passer went on to describe, in dramatic detail, their escape from Czechoslovakia, a story recounted in today’s Column One about their friendship. As I proceeded with my research, however, a mystery appeared: I could find no instance of Forman ever mentioning it. Not in the many interviews recorded over his long and celebrated career; not in his autobiography, “Turnaround.”

Czech American author Jan Novak — who did the actual writing of “Turnaround” based on conversations with his friend, Forman — hadn’t heard the story. “Milos never mentioned it,” he said.

Neither Novak nor other friends of Forman and Passer with whom I spoke doubted the story’s veracity; they emphatically confirmed my assessment of Passer as a reliable chronicler.

But still I had work to do, to confirm some basic facts. Forman’s twin sons, Petr and Matej, were too young in 1968-69 to remember much. I needed to speak with their mother, Czech actress Vera Kresadlova (whom film fans may know for her memorable performance in Passer’s 1965 masterpiece, “Intimate Lighting”).

My Czech language skills are as limited as her English, but with the help of Petr Forman, whose English is good, and his half-brother Radim Kratochvil, who is quite fluent, I was able to forward questions to their mother in Prague. She corroborated the basic time frame of Forman and Passer’s presence in Czechoslovakia in fall 1968 and subsequent departure, along with some pertinent details as Ivan remembers them. (There was one discrepancy: Passer remembers making the journey in Forman’s British-made Hillman. Kresadlova says Forman had sold the Hillman by then, and the two fled in his Mercedes.)

Novak, Passer and others offer similar theories as to why Forman didn’t speak of the escape of January 1969: He didn’t want trouble for Vera and the kids back home; and, given his international fame, neither he nor Czech authorities wanted to convey the kind of break that “defection” connotes.

Czechoslovakia owes its unfortunate history to its lot as a main stage for the great conflicts of the 20th century.

“The Communists were reluctant to excommunicate him like they did me,” says Passer, whom the Czech authorities condemned to jail in absentia. “So Milos probably helped that by not mentioning that we escaped, illegally.

“They sort of pretended they let Milos go, which of course they didn’t. Once it happened, they didn’t want the embarrassment of saying that he defected.”

Forman, even years after the fact, never cast his departure as defection, and he was vague in recounting certain details about his move in 1969 from Prague to Paris to New York.

The closest Forman gets to an explanation may be this passage from “Turnaround” about the early days in his new country:

“I flew to New York with Ivan, who had decided to emigrate outright. I didn’t have to burn my bridges to Czechoslovakia yet because I was still under my official Filmexport contract with Paramount. I entered the country with my Czech passport, on a visa that gave me the right to work in America.”

He later adds: “I still didn’t want to emigrate from the old country as Ivan had done.”

When eventually Czech authorities refused to extend his visa and the Prague film studio severed ties, Forman says, “the die was cast. I was an emigre.”

So perhaps their flight across the Austrian border in the dead of night, which for Passer became a stark demarcation between his old life and new, was less resonant for his fellow traveler, who never entirely abandoned the dream of one day moving back to the land of his birth.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.