She made an honest movie about Poland’s migrant crisis. That’s when her problems began

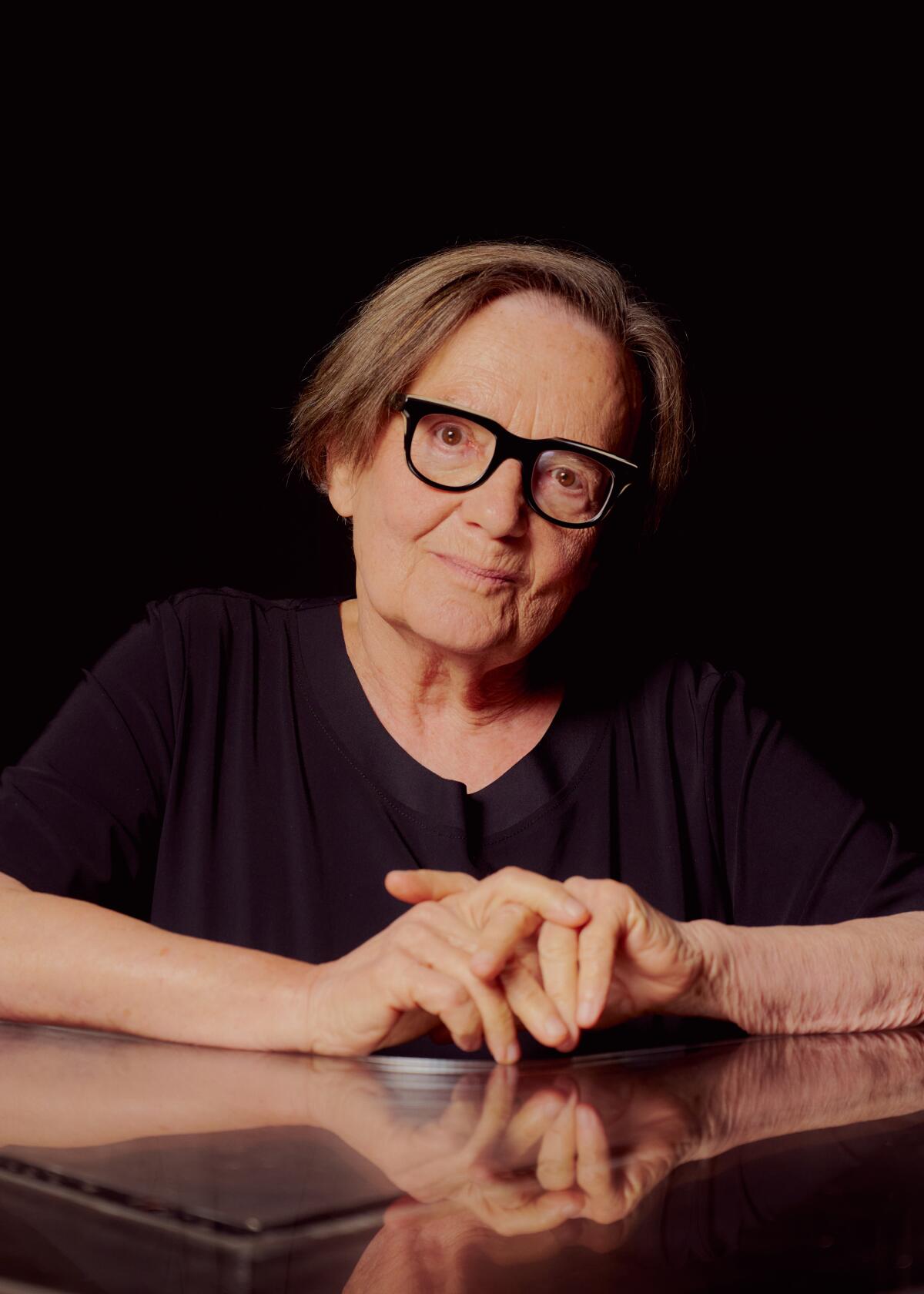

It is 10 p.m. in Berlin and Polish director Agnieszka Holland, just back from a long day on the set to take part in a Zoom interview, is too exhausted to care that she’s inadvertently sitting in front of a cut-out of Mary Poppins, of all people, in her Hollywood-themed hotel room.

Holland is visibly tired, and no wonder, given the tight production schedule on her still-shooting feature, “Franz,” which she calls “kind of an experimental biography of Franz Kafka — fragments to touch the mystery.” But the longer she talks about her extraordinary latest film, “Green Border,” set to open Friday in Los Angeles, the more her passion for the project takes over and the fatigue almost magically fades away.

A stunning refugee story, “Green Border” is both an extension of frequent themes for the writer-director (whose credits range from 1990’s “Europa Europa,” the best known of her trio of Oscar nominations, to three episodes of HBO’s landmark “The Wire”) and something that feels completely new. It also proved to be controversial even for Holland, calling forth a level of hostility in her native land that the 75-year-old filmmaker said was without parallel in her decades-long experience of uncompromising work.

“It created a lot of hate in Poland coming from the Polish government,” she remembers. “In my quite long life I’ve had very difficult experiences, but the hate campaign coming from officials was unprecedented. It was unpleasant for me, I had a lot of threats,” so much so that she found it necessary to employ full-time bodyguards.

For the record:

3:37 p.m. June 28, 2024The name of Jaroslaw Kaczynski, former head of Poland’s Law and Justice Party, was misspelled Karzynski in a previous version of this story.

The criticism started at the top, from Jaroslaw Kaczynski, head of Poland’s then-ruling Law and Justice Party, who in 2023 called the film “shameful, repulsive and disgusting.” Top Polish ministers labeled “Green Border” “intellectually dishonest and morally shameful,” compared it to Nazi propaganda films and Holland to top Third Reich functionary Joseph Goebbels, and in one case concluded that the director had forfeited the right to call herself Polish.

The government went further, denying “Green Border” a best international film Oscar entry, and mandating that theaters precede their showings of the film with a two-minute short putting forth the official point of view. “The government made some propaganda clips, showing how wonderful the Polish state was,” Holland relates. “Some cinema owners refused to show it, which was very courageous, and one government-supported cinema that had been blackmailed into showing it said, ‘We will show it, but with a caption saying all money from the showing will be given to activist groups.’”

Ironically, Holland says of the threats, “Though it was unpleasant for me, they were so violent, so aggressive, by the end they overdid it and helped the movie at the box office,” making “Green Border” one of the year’s top grossers in Poland. “And afterwards, I never had such long and important discussions with the audience, people staying for hours after the screening. Our courage to speak openly gave courage to many people. It was very touching to see this.”

Our staffers select a highly opinionated list of their most anticipated titles: Hollywood fun machines, indie big swings and the truly unmissable.

The film behind the fuss, winner of a special jury prize in Venice, is closely based on a real-life situation that is, appropriately enough, uncannily Kafkaesque. Starting in 2021, Aleksandr Lukashenko, longtime ruler of Poland’s neighbor Belarus and close ally of Russia’s Vladimir Putin, made it surprisingly easy for Middle East refugees to fly to his country. Once they arrived, they were taken straight to the border and literally pushed into Poland.

Except it wasn’t the Poland they might have expected. It was the Green Border, a heavily forested area described by the New York Times as “a two-mile-wide exclusion zone around the border” that featured “a 116-mile-long, 18-foot-high barbed wire fence” that was heavily patrolled by numerous Polish border guards. They rounded up the refugees and pushed them back into Belarus, from which they were pushed back into Poland. This back and forth and back was repeated, sometimes ad infinitum, with beatings, robberies and deaths thrown into the mix.

Holland, who is deeply versed in the dynamics of the situation, says things began with the Syrian civil war of 2015. “Europe is deadly afraid of the arrival of people where the color of the skin, the religion and culture are different,” she says. “And that was immediately used by populist right-wing governments to create an atmosphere of fear and danger.”

Lukashenko (with Putin’s likely support) opted to make things worse, opening that corridor for refugees “to destabilize Poland and Europe, to prove that the Europe of democracy and human rights is bull—,” the director continues.

Moreover, Holland relates, “the Polish government forbade access to humanitarian organizations and all media. That meant it was not only impossible to help these people lost in the forest but also to document the cruelty of the border guards.

“Kaczynski, the main political force in Poland, said something that was revelatory to me. ‘Americans lost the war in Vietnam when they allowed the media to go there and send back pictures of children burnt by napalm. We will not allow images to go out.’ So I felt it’s my responsibility to try to tell that story while it was still going on.”

Not only that, Holland was determined “to tell the story from the human perspective. It’s important to me, the feeling of reality.” Holland and her two co-screenwriters, Gabriela Lazarkiewicz-Sieczko and Maciej Pisuk, “spent hours and hours talking to different people. We finally succeeded to speak secretly to border guards, so they could share their experience, their point of view.”

Because of the controversial nature of the film, the aspect of it that took the longest was the raising of funds, which took an entire year and even included money from an American producer, Fred Bernstein. “Green Border” ended up being a Polish-French-Czech-Belgian co-production, and Holland, who for the first time served as a producer as well, said the experience gave her a renewed appreciation of the complexity of European film production.

The resulting movie tells the story from the vantage point of three distinct groups. Introduced first is a family of refugees from Syria, hoping to eventually join a relative in Sweden. Then there is a Polish border guard who wants to be doing the right thing but is not sure what that is. Finally there is a therapist who gradually takes on an activist role in her border town. Adding to the drama is a coda showing how Poland’s reaction changed when it faced another influx of refugees, this time from racially similar Catholic Ukraine.

Because Holland was so concerned about verisimilitude, she took special care with the casting. “The actors were professional actors but also real Syrian refugees,” she explains. “They did not have to imagine how the Syrians felt, they knew what it meant.” And for the local activist, Holland chose Polish actress Maja Ostaszewska, who in her off-screen life “was helping at the border with human rights activities.”

Shot in only 24 days in luminous black-and-white by cinematographer Tomasz Naumiuk, “Green Border” teems with urgency and immediacy. “It was a very special kind of work, very collective,” Holland recalls. “Some days we worked with two parallel units, with two young Polish women as directors. We did it in secret from the Polish government but we found a unity.”

Besides her “Europa Europa,” Holland has made several films dealing with Holocaust scenarios, and she admits to at one time believing that “the experience of the Holocaust, the horror humanity faced in seeing themselves capable of such things, created some kind of a vaccine against nationalism. But since Sept. 11, the vaccine doesn’t work anymore, that immunity evaporated. Slowly old habits, old demons are coming back.”

Adding to that feeling for Holland is the coincidence that the Green Border area is quite close to the former location of Sobibor, a World War II German death camp that was the site of a famous prisoner rebellion and escape. “When they escaped, the people from that camp looked exactly like these refugees did,” she notes, “and they escaped exactly to that forest.”

The possibility of the world backsliding to a horrific past is very much on the mind of both “Green Border” and its director. “It’s like when a tooth is sick, it gets worse and worse,” she explains. “If you don’t treat it early enough, you are going to lose it. The past which was never healed is frankly still present.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.