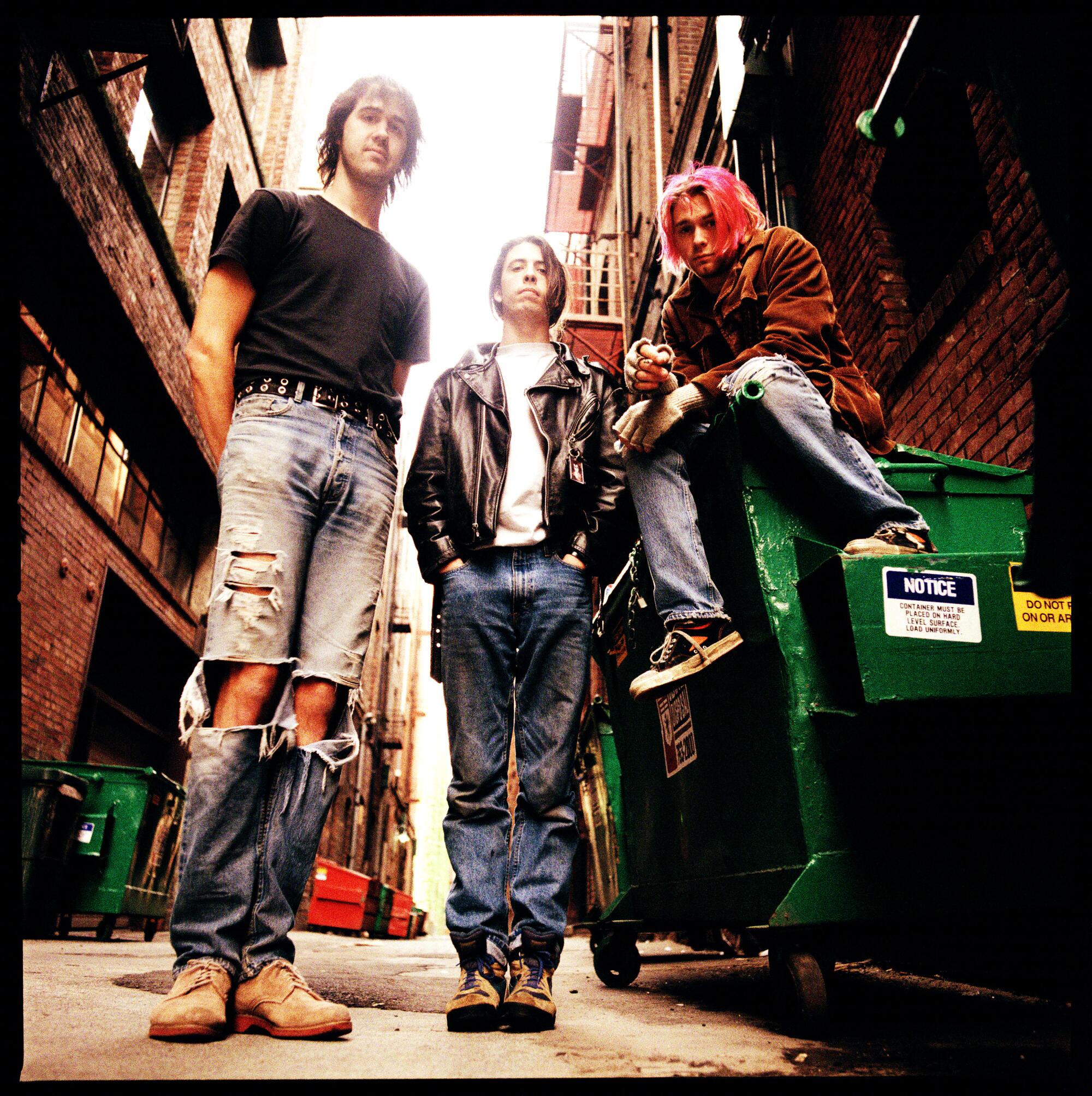

Eric Martin insists he didn’t hate Nirvana — even though he knew at the time he was supposed to.

As frontman of the Los Angeles hair-metal band Mr. Big, Martin had been fed a story that Nirvana’s overnight success in the early 1990s came at the expense of the peacocking leather-and-denim types who’d dominated rock just a few years before.

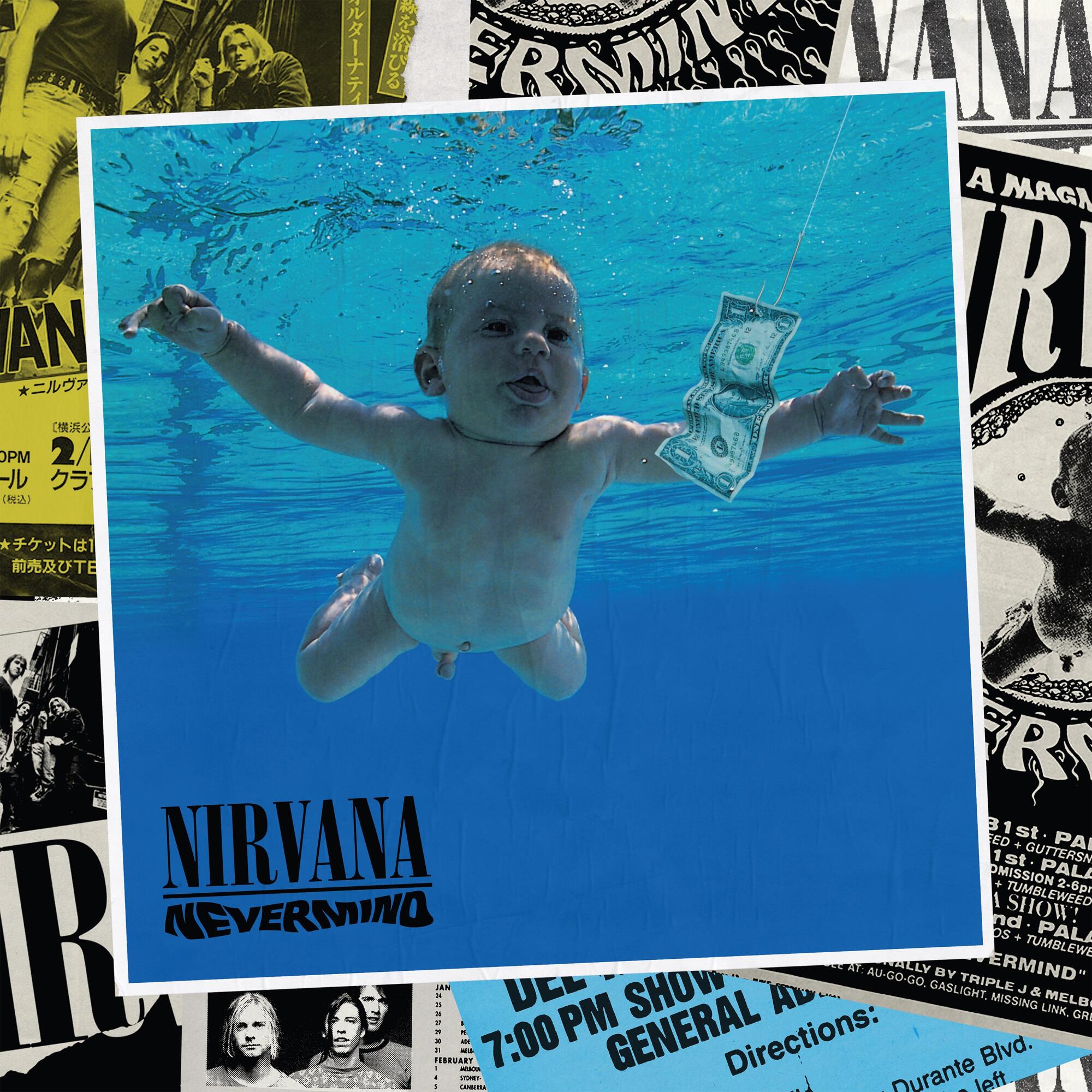

Courtney Love talks with Kurt Cobain biographer Charles R. Cross about the still-resonant depths of her late husband’s breakthrough 1991 album, ‘Nevermind.’

“Everybody said they were taking food out of our mouths,” Martin recalls of the scowling Seattle trio that crashed MTV and the Hot 100 with 1991’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” “We’d all been touring, having a great time, and then the grunge thing came in and pulled the rug right out from under everybody. Lot of guys went back to painting houses. “But I thought ‘Teen Spirit’ kicked ass,” Martin adds. “I didn’t have a f— clue what Kurt Cobain was talking about. But I liked the attitude. It still rocked.”

Martin’s generosity may have been due to the fact that Mr. Big wasn’t among grunge’s casualties (at least not yet): Five months after Nirvana upended the rock world with its album “Nevermind” — released 30 years ago this Friday — Martin and his bandmates scored a No. 1 hit with “To Be With You,” an old-fashioned hair-metal ballad in the flowery tradition of Extreme’s “More Than Words,” Mötley Crüe’s “Home Sweet Home” and Poison’s “Every Rose Has Its Thorn.”

Pretty, polished and loaded with “baby’s” and “little girl’s,” “To Be With You” was precisely the type of tune that Nirvana was assumed to have killed with Cobain’s disaffected songs about feeling “stupid and contagious.” Instead, it spent three weeks atop the singles chart and drove Mr. Big’s “Lean Into It” LP to platinum sales.

Says Martin with a laugh: “It’s why my 16-year-old boys have four years of college paid for.”

Decades later, the well-received power ballad demonstrates that the conventional wisdom about “Nevermind” — that it was “a death knell,” per REO Speedwagon’s Kevin Cronin, for bands that burned through Aqua Net by the case — isn’t entirely accurate.

“Grunge wasn’t a mass extinction event for that earlier hard rock,” says Tony Berg, the veteran producer and A&R executive who signed Beck to Nirvana’s label, Geffen, in the wake of “Nevermind”’s explosion. “But there was the almost instantaneous perception that it was so not cool. While there may still have been an audience for it, especially in mainstream America, the cognoscenti certainly was not wondering what the next Warrant record was gonna sound like.”

And not just Warrant: Any number of hair bands that had been riding high in the mid to late ’80s — from Whitesnake to Slaughter to Winger, whose frontman Kip Winger has described the grunge era as “the Dark Ages” — suddenly found themselves crowded out from the table by the brooding likes of Nirvana, Pearl Jam and Soundgarden, all of which put out seminal albums within weeks of one another in the fall of 1991.

Desmond Child, who made his name writing flashy hits for Kiss (“I Was Made for Lovin’ You”) and Bon Jovi (“Livin’ on a Prayer”), compares seeing the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” video to “Elvis Presley watching the Beatles on TV.”

“My own manager sat me down — I was in my 30s — and he said, ‘Well, basically, you’re all washed up,’” Child recalls. “I was stunned. I was like, ‘At this age?’”

Yet as producer and Garbage co-founder Butch Vig points out, this perceived change in taste was driven in large part by industry gatekeepers, most of them white and college-educated, rather than by fans. “Trust me, there were still people out there who wanted to hear Tesla,” says Vig, who oversaw the recording of “Nevermind” and went on to produce Smashing Pumpkins’ “Siamese Dream” and albums by Sonic Youth and L7.

“Hair metal never had a Comiskey Park moment,” says longtime record exec Jason Flom, referring to the ugly night in 1979 when thousands of Chicagoans descended on that baseball field to burn an enormous pile of disco records. Adds Flom, who signed Skid Row to Atlantic: “There wasn’t an open rebellion against the music.”

Indeed, Bon Jovi was still playing arenas and stadiums in 1993, while a 1994 tour by Aerosmith — then enjoying a comeback that included its first No. 1 album, “Get a Grip” — outgrossed that year’s traveling Lollapalooza festival with Smashing Pumpkins and Green Day, according to the trade journal Pollstar.

Still, for a record biz attuned to seeking out the next big thing, expending resources on a muscle-teed young act like Trixter was viewed as “pretty much investing in the past,” as Berg puts it.

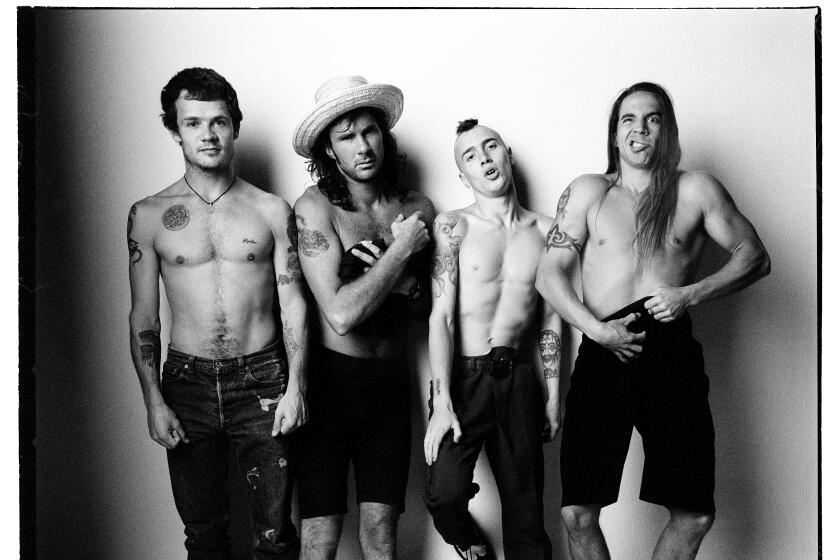

As ‘Blood Sugar Sex Magik’ turns 30, here’s the inside story of the making of the classic album, as told by the band, producer Rick Rubin and more.

Luke Wood, who worked in marketing at Geffen in the early ’90s (and later headed up Dr. Dre’s Beats Electronics), remembers a meeting about a hard rock band called Roxy Blue then signed to the label.

“I can’t make a judgment as to whether they were better or worse than Poison or Warrant, but they were in that same vein,” he says. “And there was just zero conversation about them. No ‘Let’s listen again.’ We’d moved on.”

So had decision-makers at radio and MTV. Rick Krim, MTV’s director of talent and artist relations at the time, notes that the influential cable network played Alice in Chains’ “Man in the Box” before “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

“We were ready for a change,” he says, even before grunge blew up. “Our mindset was, Let’s shake it up and try something new.”

With its vaguely defined countercultural air — and its not-so-secret tunefulness — grunge met that need, especially after “Nevermind” knocked Michael Jackson’s “Dangerous” out of the top spot on the Billboard 200 in January 1992, a hugely symbolic victory for alternative rock that set every major label in the business scrambling to find its own Nirvana. (By the end of the ’90s, “Nevermind” had been certified for sales of more than 10 million copies in the U.S. alone.)

“A&Rs pitched me on thousands of copycat bands,” says Vig, who adds that a kind of grunge template quickly developed: “fuzzy, distorted guitars; aggro singing in the chorus; lyrics about how bummed out and frustrated people were.” A report in Spin magazine in 1992 said Madonna was searching for grunge acts for her new Maverick label; bidding wars broke out like the one over Seaweed, a punky outfit from near Seattle with a handful of indie releases — and an appearance on MTV’s “Beavis and Butt-Head” — to its name.

“They were courted like they were Def Leppard,” Wood recalls with a laugh.

Yet in retrospect, tastemakers’ preoccupation with grunge threatens to misrepresent where the music sat in the larger context of pop music in the 1990s.

“Nirvana wasn’t really mainstream,” says Mark Kates, another Geffen exec who handled A&R and alternative radio promotion. “They were successful, and their impact was huge. But it’s not like they took over Top 40.” The week that “Smells Like Teen Spirit” peaked at No. 6 on the Hot 100, the song was bested by hits from Color Me Badd, Mariah Carey and MC Hammer; “Nevermind’s” second single, “Come as You Are,” got no higher than No. 32, well behind a down-the-middle smash such as Vanessa Williams’ “Save the Best for Last” (which, as it happens, bumped Mr. Big’s “To Be With You” from No. 1).

Grunge bands were big on MTV, no doubt about it; their videos offered viewers a window “into a whole culture,” Krim says, just as Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg were doing at the same time with their gangsta-rap “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang.” The music informed fashion and movies and defined how Generation X presented itself; it also moved rock away from hair metal’s depiction of women as bikini-clad arm candy.

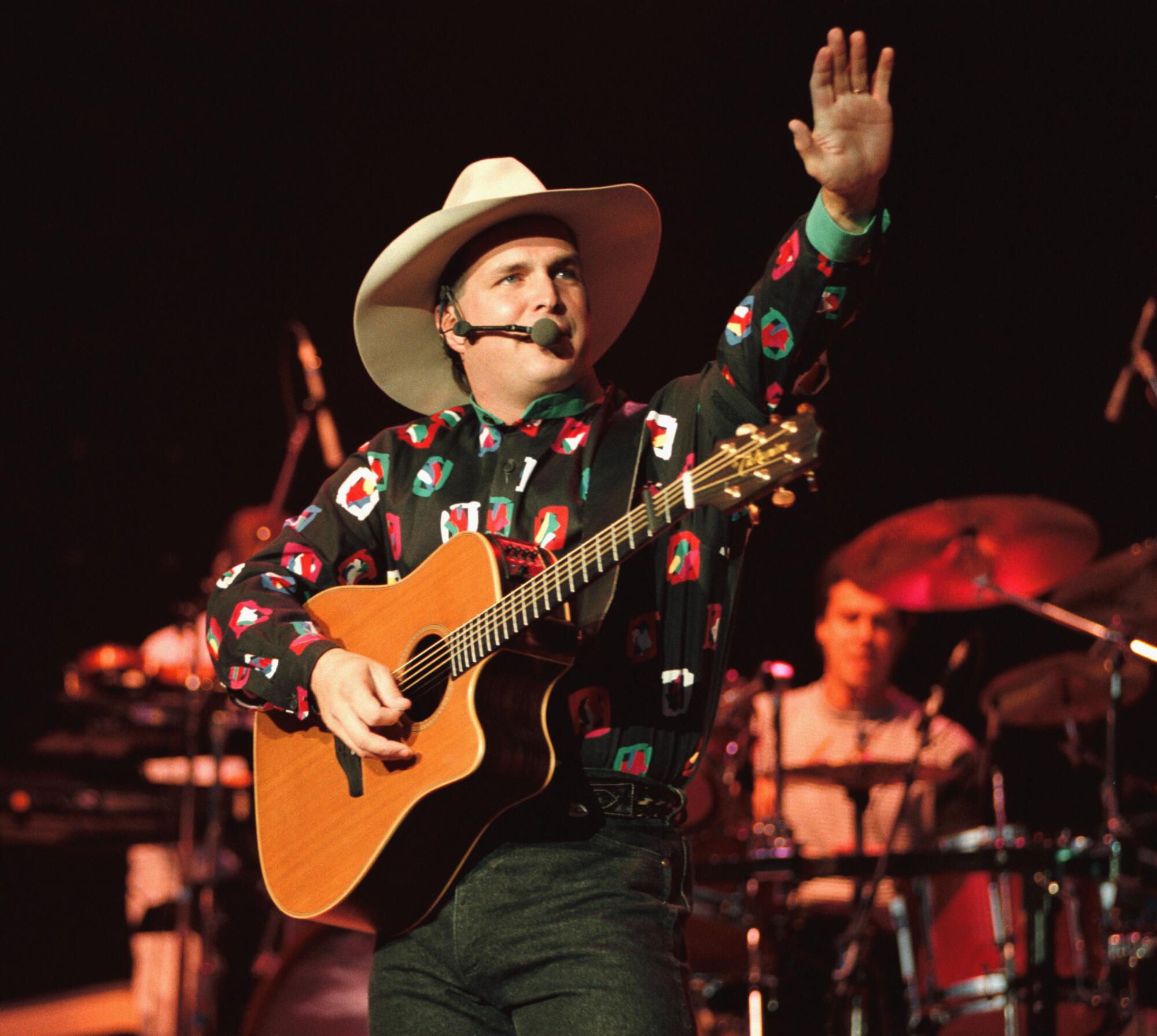

For all its influence, though, grunge remained a relatively limited commercial phenomenon, at least compared with juggernauts like Garth Brooks, Michael Bolton and the “Bodyguard” soundtrack. Krim points out that when Pearl Jam recorded its “Unplugged” special in 1992, the band’s taping was the third one in a single night, following earlier, more humanely scheduled performances by Carey and Boyz II Men. “I think we started at midnight,” he says.

Looking back from an age thoroughly defined by hip-hop, the tension between grunge groups and hair-metal bands can start to seem like the narcissism of small differences.

Does Skid Row’s “Monkey Business” contrast so dramatically now with Alice in Chains’ “Man in the Box”? And what to make of Guns N’ Roses, in some ways a classic hair-metal band that brandished enough edge to thrive well into the ’90s? (That Cobain and GNR’s Axl Rose famously feuded while recording for the same label — here were two grown men taunting each other like schoolboys from the stage of MTV’s 1992 Video Music Awards — calls to mind the current beef between Drake and Kanye West, about which no one is likely happier than their shared partners at Universal Music Group.)

Eric Martin of Mr. Big remembers hearing Atlanta’s Collective Soul, which had a top 20 hit in 1994 with the manicured “Shine,” and thinking, “Why’s this called grunge? This is exactly what we’re doing.”

Like late-stage hair metal, grunge was eventually bled dry through the corporate exploitation of second- and third-generation acts — your Sponges and Creeds and Candleboxes. “It became about just following a trend,” says Wood. “It was like TikTok: the Grunge Challenge.”

By the late ’90s the music industry had moved on, as it always does, to electronica and teen pop and nu-metal — the last a kind of brutish remix of grunge’s white-boy blues — and not without many of the figures who’d been instrumental in creating earlier crazes. After leaving L.A. to resettle in Miami, Desmond Child helped launch the turn-of-the-millennium Latin-pop boom when he cowrote “Livin’ la Vida Loca” for Ricky Martin; Bon Jovi remade itself with an eye on the fist-pumping country fans who kept Brooks’ “Ropin’ the Wind” album at No. 1 for a combined 18 weeks before and after “Nevermind.”

Even Nirvana’s drummer, Dave Grohl, went on after Cobain’s 1994 suicide to fuse grunge and hair metal, more or less, with Foo Fighters, his arena-packing hard-rock group that will be inducted next month into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. (Nirvana was inducted in 2014, while Pearl Jam, still a touring behemoth today, got in three years later.)

Any Nirvana lover wonders what kind of music Cobain would’ve made after grunge’s inevitable fade; his death after only one additional studio album, 1993’s blistering “In Utero,” recast his success as a cautionary tale about fame.

Yet the songs he wrote and recorded in his short life continue to resonate decades later. Billie Eilish and Post Malone are vocal fans, and you can hear his pained melancholy in the work of Soundcloud rappers like the late Lil Peep; Lil Nas X recently cut in Cobain as a credited songwriter when a melody from Nirvana’s “In Bloom” found its way into his song “Panini.”

Vig recalls the day he flew to London to meet with Shirley Manson about forming Garbage, the electronic pop group that paved his own way out of grunge. “Afterward I met up for beers with Flood and Alan Moulder” — fellow producers who shaped the sound of alternative rock — “and when I got to the pub, I sat down and they were all looking at me.

“‘Have you heard what happened?’” they asked him. “‘Kurt Cobain is dead.’ I got up, went back to my hotel and flew straight back to the states,” Vig says. “It was like one part of my life started on the same day that another part ended.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.