Forty years ago, MTV changed music forever. These four rock icons remember all too well

When it debuted on Aug. 1, 1981, MTV was a business and technology experiment without much downside and without much chance of succeeding.

Warner Amex Satellite Entertainment Co., only slightly better known as WASEC, was a joint venture between Warner Communications and American Express. Their goal was to sell goods and financial services interactively into homes through newly created black boxes that sat atop console TVs — giant bricks with buttons that communicated with just-launched satellites beaming the first cable television networks. CNN and HBO were already running; a cable exec and rock ‘n’ roll fan named John Lack eventually convinced WASEC that a channel showing prerecorded music clips (mostly live footage; “music videos” as we’d come to know them didn’t much exist yet) would besot teenagers and therefore pimple cream and soft drink advertisers.

The good news was that the record companies had a few boxes full of these short clips just sitting around and would give them to this startup channel for free; the bad news was that a few boxes of clips could barely fill a 24-7 channel and most of the footage was either dull, incompetent, profoundly silly or even potentially career-threatening for homelier artists who’d managed to hide in the shadows until then.

MTV launched with approximately 250 videos. The first weeks and months, which were not carried in either New York or Los Angeles, were filled mostly with dreary videos from has-beens, nobodies or earnest American rock bros like Journey who felt about dressing up and lip-syncing the way Allen Iverson felt about basketball practice. It wasn’t until MTV played more cinematic videos from fabulous-looking British exhibitionists like Duran Duran, Culture Club and A Flock of Seagulls that the network landed on its visual and musical identity: tuneful outrageousness with a narcissistic love for the camera.

About a year later, still struggling for ad dollars and household penetration, MTV execs, trained in the segregationist playlists of rock radio, bowed to record-label pressure and aired the new “Billie Jean” video by Black pop star Michael Jackson. Months later, with ratings ticking upward, they’d screen Jackson’s transformational “Thriller” video every hour on the hour, and Michael and Madonna would become the network’s prom king and queen. Squadrons of hair-metal pretties followed the new-wave glamourpusses, and even paragon-of-rock-virtue Bruce Springsteen had to wiggle his bum for pop culture’s new star-making machine.

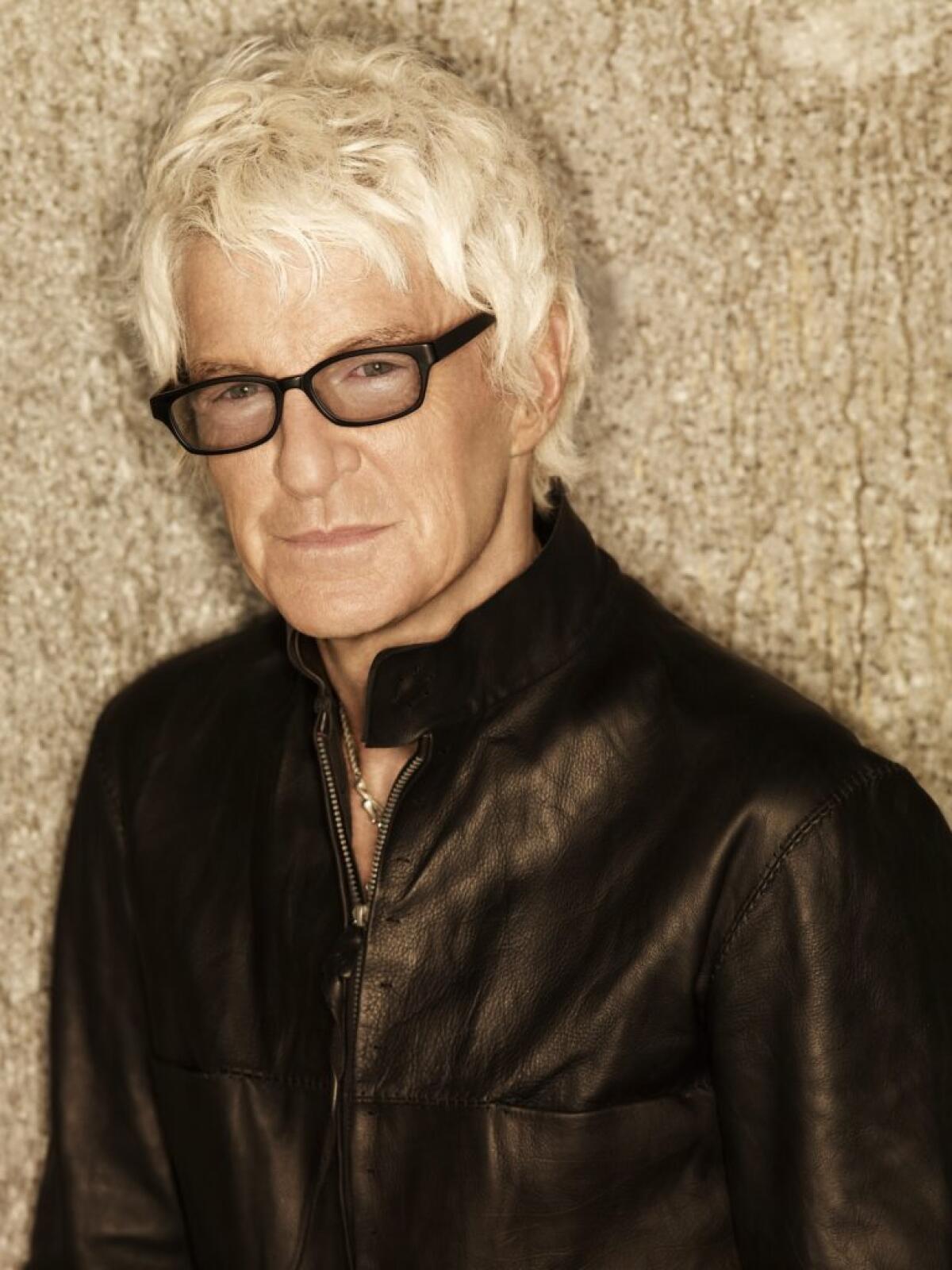

To commemorate MTV’s 40th anniversary, we’ve gathered four original stars of the music video revolution — REO Speedwagon’s Kevin Cronin, Billy Idol, Huey Lewis and the Go-Go’s Kathy Valentine — to reflect upon the salad days of music videos and MTV’s unmatched power to make musicians wildly rich and famous. Today, ViacomCBS owns MTV, which these days seems to be singularly and bizarrely dedicated to block-programming Rob Dyrdek’s “Ridiculousness,” while music videos, now user-generated in 15-second spurts on TikTok, have been reimagined by and for teens for whom an old-fashioned four-minute video might as well be “Lawrence of Arabia.”

“The market is so fragmented today,” says Lewis. “You can’t have a hit now like we used to. Because then, everyone was focused on one thing at the same time. Everyone was watching MTV.”

What’s the first time you remember seeing a music video?

Billy Idol: Even before MTV, there were bands making music clips. The Beatles did loads of them, for “Paperback Writer,” for “Strawberry Fields.” In England in the ‘70s, there was a TV program called “The Kenny Everett Video Show.” Kenny Everett was a former DJ, and in the middle of his show, he would have a band like the Police play, and a bloke named David Mallett would direct it. The show also had a dance troupe called Hot Gossip that would perform these sexy routines to the hits of the day. David went on to direct loads of music videos, including “White Wedding,” and Perri Lister from Hot Gossip became my choreographer and girlfriend. Those videos and dance routines became the look of MTV.

Huey Lewis: The first time I saw a video was on a show called “Videowest” in San Francisco. This was 1977. A girl named Kim Dempster came to us and said if we would let her film a video and show it on her channel then we could have the video. So we made two videos with a handheld camera, and I basically pinched old “Hullabaloo” and “Shindig” ideas and goofed around. Those videos actually got us our record deal.

Kevin, you were one of the earliest, and in retrospect unlikeliest, stars of MTV. During the very first two hours of MTV, there were eight different REO Speedwagon videos played more than a dozen times. What were you even doing making videos back then?

Kevin Cronin: Those videos you’re talking about are not my finest moment as a performing artist. I think we made four in one afternoon. We didn’t really know who or what we were making them for. MTV wasn’t even on the air yet. But our “Hi Infidelity” album was No. 1 throughout 1980 and ‘81, so the label had us make some clips. Most were just performance clips. There was one, though, for “Keep on Loving You” [the 17th video ever played on MTV] that begins with me on a shrink’s couch, talking about the girl in the song. The video is mostly our band performing, but it also features this beautiful model playing the subject of the song. And at the end of the video, you finally see the shrink, and she’s this gorgeous woman wearing a pair of black-rimmed eyeglasses, her hair up in a bun. She takes off the glasses, lets down her hair and, yes, she’s the same model from the video. It was the biggest cliché.

Billy, you were living in New York in the early ‘80s when MTV started. Were you keen on it right from the start?

Idol: Bill Aucoin, who managed both me and KISS, told me as I was moving to America that there was going to be this 24-hour cable music channel. So I kind of knew. If you were like me and had a bit of a punk image, radio in the U.S. didn’t want to play your music because they thought it didn’t attract advertising dollars. MTV proved what a load of bollocks that was.

Why were Brits like yourself so good at making music videos at a time when a lot of American artists felt that it was beneath them?

Idol: I think we just took it more seriously. If you came out of punk, you were invested in creating your own image. I wanted my image to be as edgy as it could be while still getting on TV. For my videos I borrowed a lot from old silent horror movies, like “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.” There were a couple of black-and-white Boris Karloff images I took from a horror book I had. There was one where he’s on an altar with tons of crosses around him, and I just ran with it for “White Wedding.” I thought, let’s do that but in color.

Lewis: Chrysalis wanted us to do a big, high-powered video for our first single, “Do You Believe In Love.” So they hired this director, he was an ad man, and he had us all dressed up in pastel shirts that matched the pastel backgrounds, and we shot 20-hour days. This is the video where we’re all in bed with the girl. Anyway, a week later we go to the label to see the rough cut. There’s a bunch of people from the label there, a bunch of people from the video and the whole band, probably 30 of us in all. The director gets up and says, “Now, this is just the rough cut; it’s going to look so much better when it’s colorized.” And then he shut off the lights and they play the video, and it was f—ing horrible. My heart sank. There was no discernible direction. It was the craziest thing. When the video ends, everybody stood up and gave it a standing ovation! I said to myself, clearly anybody can do this. So from then on we took creative control over our videos.

Kathy, what was your attitude toward making music videos?

Kathy Valentine: Really freaking annoyed. The day we shot “Our Lips Are Sealed” was our first day off in quite a while. It was half-baked and low budget, and I remember thinking, why are we aimlessly driving around in this cool car, doing nothing? There was no plan. It was my idea to jump in the fountain in Beverly Hills because I thought maybe we’d spontaneously get in trouble on camera. But nothing happened at all. I hated it until we got to the scene where we were playing live at the Viper Room, because it was really important that people saw us with instruments. That was the only part that made sense to me.

Now, when the video got played on MTV, then I got it. That’s how a lot of young people found out about us. Relentless touring and being dumped into people’s living rooms on MTV. I remember being embarrassed about the video at the time, like why can’t we have something cool and slick and professional looking? But in a way it presented us like we were. No matter how hard we tried, nothing ever looked slick. It kind of worked in our favor.

Who was the first artist you saw on MTV who really made an impression on you?

Idol: Prince. His whole image was fantastic. The raincoat and the rubber stockings? He was built for MTV.

Cronin: For me it was David Coverdale in that famous Whitesnake video with Tawny Kitean [“Here I Go Again”]. We were just finishing an album at the time and starting to think about the music videos. I was just like, “Guys, there’s no way that I’m going to out-cocky David Coverdale.”

Lewis: In the beginning, MTV played pretty much everything that they could get their hands on. There were some horrible videos out there. … The Pat Benatar one with the Nazis? [laughs] But MTV played them every goddamned hour because that’s all they had. And people were watching because cable TV was brand new. In my band, nobody liked making music videos. They thought, “We’re musicians. What are we doing this stupid stuff for?” We didn’t want to become video artists. We had to become video artists. It was thrust upon us.

What’s the worst experience you had making a music video?

Idol: Video shoots would go on for days. Video hell, we called it. “Eyes Without a Face” took forever. Days and days with no sleep. Then, right after, we flew somewhere for a concert, and we were at some university where I finally fell asleep on a lawn. When I woke up, there was a sheriff’s gun pointed at my head. I had this beautiful, ripped Vivienne Westwood outfit on, but the sheriff thought I was some bum. But my bigger problem was that I hadn’t taken out my contact lenses in days, and when I fell asleep and woke up, my eyes were just pouring water. But the sheriff wouldn’t let me take out the contact lenses. I ended up going to the hospital because the lenses scraped my corneas. So, yeah, a victim of video hell. Still got the scars.

Lewis: We did this one, “Doing It All for My Baby,” which was a Frankenstein takeoff for some reason. We were all dressed up as monsters and ghouls. It didn’t suit the song. It didn’t suit anything. I had the Tower of Power horns in the video, and at one point we put harnesses on them and these weird costumes and they were hanging from the ceiling. I remembering looking at the guys and they were f— miserable, man. I bet we spent a quarter of a million dollars on that video. It got played about four times.

There came a point, after MTV had helped make you famous, that they more or less stopped playing your videos. Was that a hard thing to accept?

Cronin: For us, there was a direct correlation between that and “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” I thought that video was awesome, but it was a death knell for us temporarily. We went from headlining sold-out arenas to playing the Clark County Fair somewhere in Missouri with a freaking Ferris wheel in the distance. We owned the ‘80s. Well, you can’t own forever.

How about you, Huey?

Lewis: When MTV pulled our videos? I just went to my mansion in Malibu, and I was fine. [laughs] Honestly? It wasn’t that big a deal for me. MTV was such a bright light that it was a relief not to be on MTV after a while. It was a great way to break a band, it was a great way to sell records, but it hurt your credibility a little. We were much more of a rock ‘n’ roll band than a pop band, but our videos signaled that we were frivolous and funny. Which is fine — I don’t regret anything — but for me, not being on MTV was no big deal.

Broadly speaking, was MTV a force for good in music?

Idol: Artists like me weren’t getting a fair shake on the radio, so it helped to break us. But eventually, a lot of artists got in big with Pepsi or someone, and they could afford to spend a million dollars on a video, and it started to get a bit boring. Then reality TV took over. It was all going to end anyway.

Valentine: The Go-Go’s would never have had the success we did without MTV. But overall, was it a good thing? I don’t know, you’ve got to take the good with the bad. I grew up in Texas listening to ZZ Top, and they were this lowdown, dirty band. And then MTV came along and ZZ Top became this big, slick, cartoony thing. They certainly knew what they were doing, and became huge after those videos. But when I was 12, they were my idols.

What’s the last time you watched MTV?

Idol: I have a girlfriend who likes the old ‘80s videos, and sometimes they show the best of the ‘80s on MTV, so we’ll watch that. Or is that VH1?

Valentine: To be honest I didn’t even know it was still on. But back then, I would stay up all night and put MTV on and just have it run in the background. I discovered a lot of music that way. MTV was your friend; it was the soundtrack to everything.

Cronin: You can’t overestimate the importance of MTV in the ‘80s. It started slow, but once it hit, man, it was everywhere, and if you had a new record out and your video wasn’t on MTV, you were kind of f—.

Lewis: Having everyone tuned in to that one station, watching those videos day and night? That was an amazing time.

Billy Idol has a new EP scheduled for release in September; Huey Lewis & the News’ latest album is “Weather”; REO Speedwagon is on tour; Kathy Valentine is the author of “All I Ever Wanted: A Rock ‘n’ Roll Memoir.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.