‘A magic world’: An oral history of the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ ‘Blood Sugar Sex Magik’

When the Red Hot Chili Peppers moved into a haunted Hollywood mansion in the spring of 1991 to make the album that would become known as “Blood Sugar Sex Magik,” the band, and pop music, was at a crossroads.

A young singer named Mariah Carey was ruling the album charts with her self-titled debut. Progressive metal band Queensrÿche was competing in the top 10 with the soundtrack for “New Jack City,” R.E.M.’s “Out of Time” and L.A. singing trio Wilson Phillips’ breakthrough album.

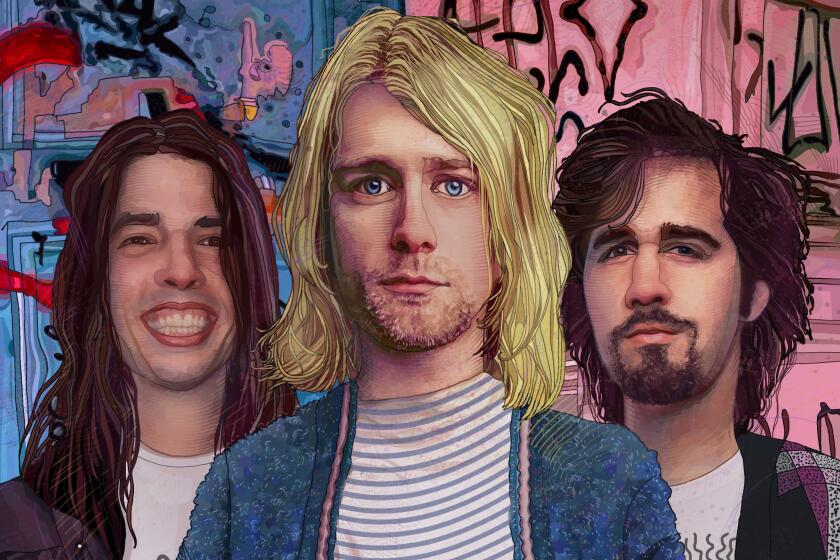

Twelve miles away at Sound City Studios, Nirvana, newly signed to Geffen Records, was tracking “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and the rest of the songs that became “Nevermind.” Soundgarden, recently inked to A&M, was holed up in Hollywood and elsewhere recording “Badmotorfinger.” In Seattle, Pearl Jam was working on its debut album, “Ten.”

Legend has it that Nirvana’s ‘Nevermind’ and the grunge boom ended hair-metal careers and dominated popular music. An in-depth look back tells another story.

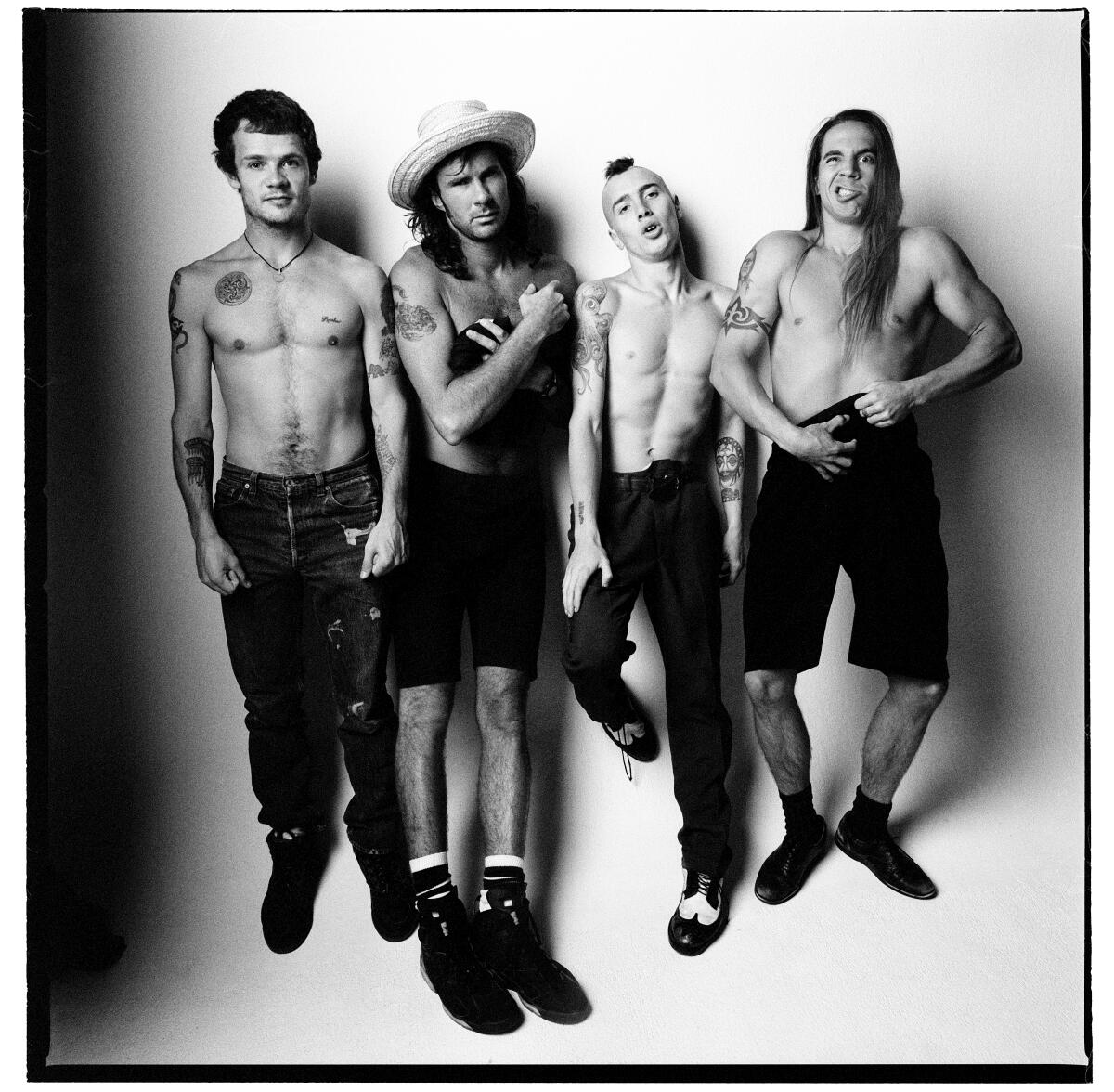

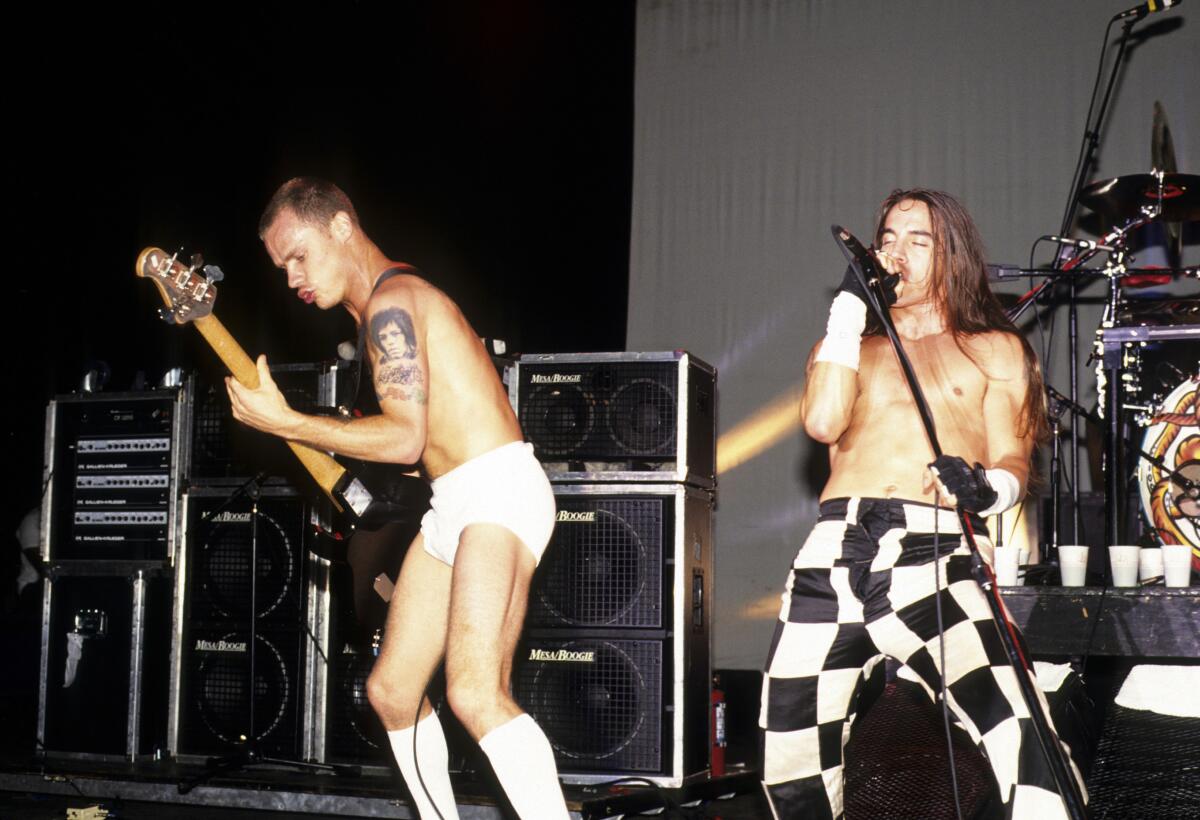

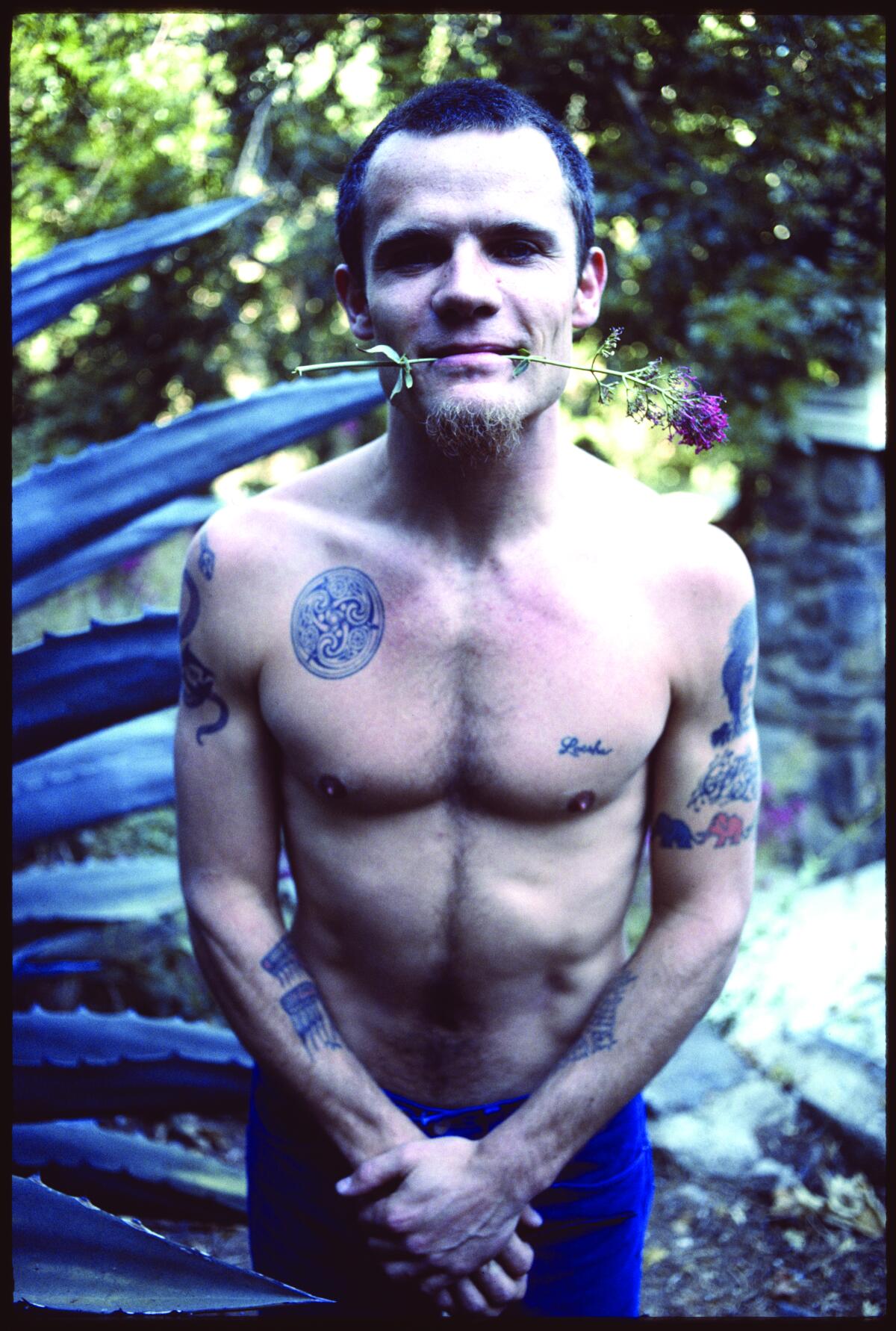

The Red Hot Chili Peppers, formed in 1983 by Fairfax High School classmates Anthony Kiedis, Flea (born Michael Balzary), Hillel Slovak and Jack Irons, had already released four albums by then. While 1989’s “Mothers Milk” had been a modest success, the band’s music — punk-indebted Muscle Beach funk-rock — lagged behind their well-cultivated image. Their shirtless dude demeanor was typified in the artwork for 1988’s “The Abbey Road EP,” which saw the group riffing on the Beatles album cover — crossing a street, naked but for socks covering their privates.

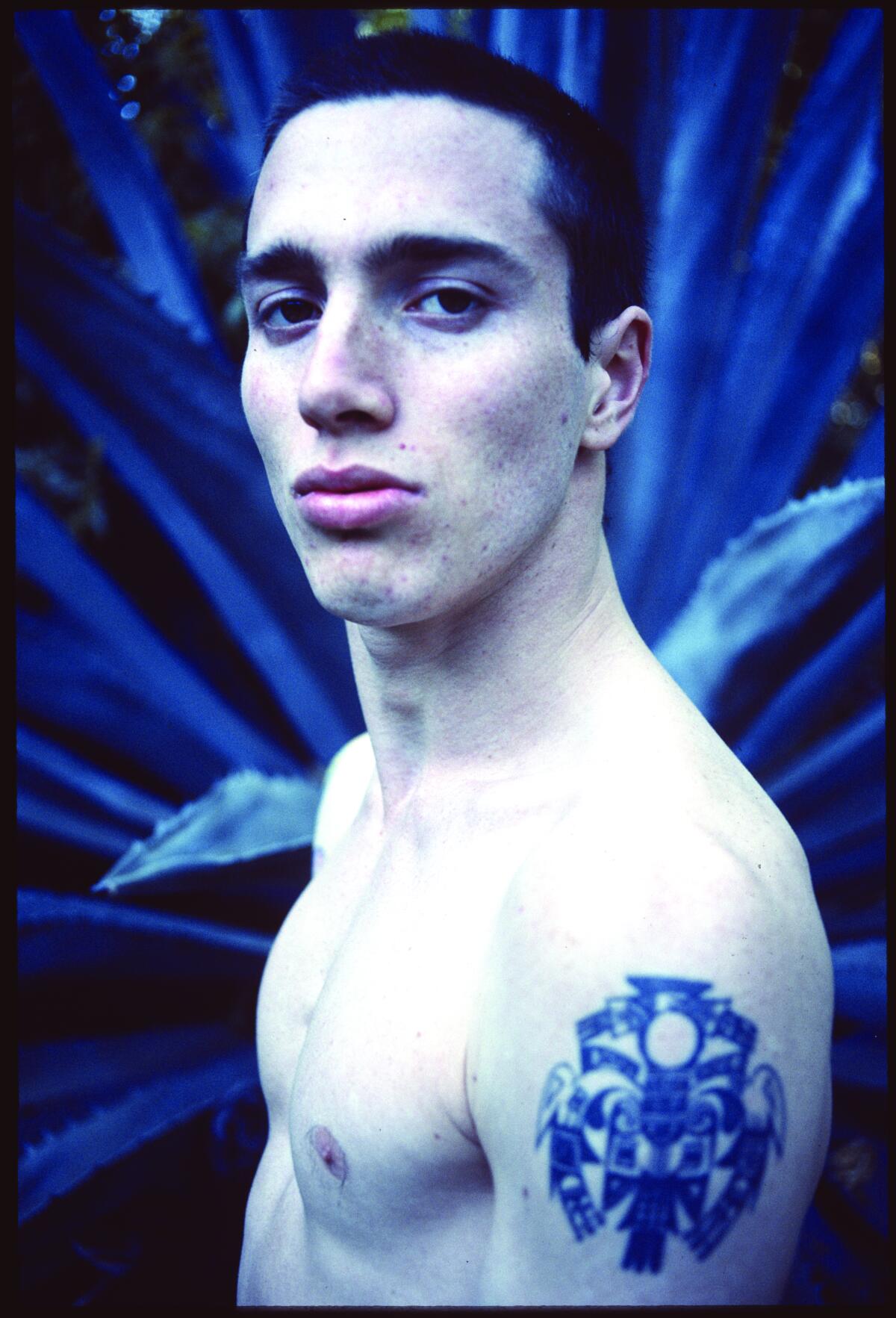

A half-decade of nonstop touring and libertine excess had already taken its toll: Slovak fatally overdosed on heroin in 1988. Crushed by the loss of his friend, Irons quit not long after. Flea and Kiedis forged ahead, ultimately hiring drummer Chad Smith and a young Red Hot Chili Peppers super fan, guitarist John Frusciante, to fill those roles.

“Mother’s Milk,” the first album to feature Frusciante and Smith, would be the band’s swan song for EMI Records. As MTV added the band’s cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground” into rotation, executives from Geffen, Epic and Warner Bros. wooed them. Warner’s legendary chairman, Mo Ostin, eventually won the bidding war.

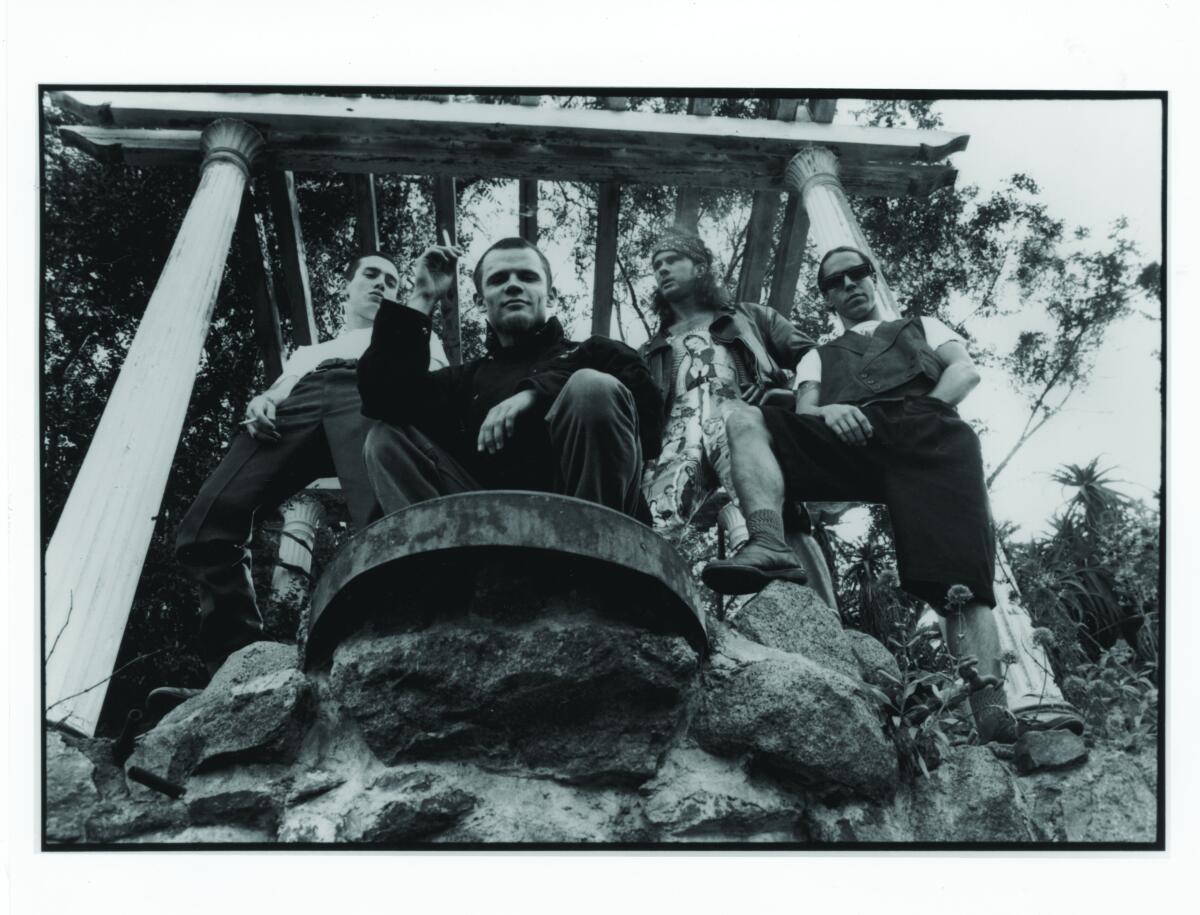

The Chili Peppers also committed to working with producer Rick Rubin, who was well on his way to becoming the Zen-like king of rock and rap through work with Run-D.M.C., Slayer and the Beastie Boys. Instead of a typical recording studio, Rubin and the band opted to rent a house in Laurel Canyon. There, isolated for two months starting in April 1991, the band, crew, and a series of invited and uninvited guests helped create one of the quintessential L.A. rock albums.

Courtney Love talks with Kurt Cobain biographer Charles R. Cross about the still-resonant depths of her late husband’s breakthrough 1991 album, ‘Nevermind.’

“Blood Sugar Sex Magik,” featuring “Under the Bridge,” “Breaking the Girl” and “Give It Away,” was released on Sept. 24, 1991, the same day as Nirvana’s “Nevermind.” It would become the Chili Peppers’ critical and commercial breakthrough, eventually selling more than 7 million copies. “Before ‘Blood Sugar,’” says Kiedis, “we were relatively unknown.” After, he continues, “I remember walking down my street in the Hills and cars driving by and hearing our songs coming out of the radio.”

Thirty years later, the band and its team sat down to tell the unlikely story of its creation.

Flea, bassist: Losing Hillel was devastating, but we knew that we wanted to keep playing music. When we found John and then Chad, we found this unit. John was only 18, and he loved the Chili Peppers.

John Frusciante, guitarist: It felt like we lived in a magic world where everything came out of us really fluidly. We felt connected all the time.

Anthony Kiedis, vocalist: John and Flea have this magical relationship, especially when they’re playing their guitars together. They just fit.

By the time they’d finished promoting “Mother’s Milk” in 1990, the band’s contract with EMI was up. “Mother’s Milk” had gone gold, radio was playing the Peppers’ cover of “Higher Ground” and the record industry was awash in compact disc profits. The timing was perfect to be free agents.

Flea: Our lawyer was saying, “You’re in a position to get a really good record deal right now.” It always seemed like a thing that happened to other people. We just put on our wacky clothes and made our crazy music.

Steven Baker, former Warner Bros. VP of product management: When the band became available, I went with Mo and Lenny [Waronker, Warner Bros. president] to see them. We took a plane up to Kaiser Convention Center in Oakland. The band was amazing. The audience was insane.

Flea: All of a sudden it was actually happening. We were being offered more money than I’d ever imagined.

At first, the band committed to Epic Records, which offered a larger advance. Ostin wasn’t finished, though.

Smith: He called each one of us at home. Mo Ostin! Who calls the f—ing drummer?

Flea: I get this call from Mo, who is one of the most respected record company guys in the world, telling me, “Hey, I understand you’re going with another record company, but I just want to say that I really enjoyed meeting you guys. You’re good kids, and I think you’re going to have a great career.” It really touched my heart.

Smith: Warners had Jimi Hendrix, Prince, Madonna, Neil Young — a real artists label.

Flea: Mo was like, “However you want to make this record, take all the time, spend what you need, have the freedom, be creative. Let your freak flag fly.”

Freak flag hoisted, the band needed a producer and hired the now-legendary Rubin.

Lindy Goetz, former Red Hot Chili Peppers manager: If I remember correctly, we tried to get Rick for the second album, but he didn’t want to do it.

Rick Rubin, producer: I remember feeling that the original members, before Chad and John were in the band, didn’t trust each other. It wasn’t anything said. It was the energy in the room and the way they looked at each other. The band I met for “Blood Sugar Sex Magik” was entirely different. They were filled with love and confidence.

Kiedis: I’m a person of extremes, and for most of the ‘80s — until maybe ’88 or so — I had gone down this rabbit hole of narcotics abuse. I was self-medicating, until I realized that the thing that I was treating myself with happened to be killing me.

The Peppers were moving away from the party life and got to work.

Flea: Five days a week we were in this rehearsal studio called the Alley in North Hollywood, playing every day, writing and jamming like crazy.

Frusciante: I stopped going out to clubs and trying to be a man about town. I started painting and drawing and making weird four-track recordings.

Kiedis: Most of the lyrics were written either at my house — at the time, I lived in Beachwood Canyon — or at the rehearsal studio.

Flea: Every day I would come home from the rehearsal studio and go, “That was a bitchin’ thing we came up with.” It would just be a bridge or an intro or a little part, but every day it felt like that.

Frusciante: Rick would come to rehearsal and just observe. A lot of the time he wouldn’t even say anything; he’d just sit on the couch. We’d jam for an hour, and he’d fall asleep.

Flea: Rick saw things in a way that we never did.

Rubin: The band had written their best songs to date. I knew we could record them honestly with the aim of capturing their energy. No more and no less.

Their disappointing studio experiences led Rubin and the band to seek somewhere in L.A. that might serve as a combination boarding house and recording studio. They found it at 2451 Laurel Canyon Blvd., in a home formerly occupied by actor Errol Flynn.

Rubin: I thought the band might be inspired by recording outside of the traditional studio.

Brendan O’Brien, engineer: We originally found a really cool place up on Mulholland, but there were too many neighbors. We would have to stop at 8 or 9 o’clock every night. That wouldn’t work.

Flea: I remember, philosophically, it being really exciting, the idea of not being in a recording studio and having to deal with their rules if I wanted to walk down naked in the morning smoking a joint and playing a funky bass line.

Gavin Bowden, director of the 1991 promotional film”Funky Monks” (and Flea’s brother-in-law): This wasn’t Downton Abbey. It was just a big house built in the early 20s, maybe a bit before that.

Flea: It was the nicest house I’d ever stepped foot in in my life — well, except when we went to David Geffen’s or Mo Ostin’s.

Goetz: We wound up bringing all the equipment in — the board, the mics, whatever it took. Brought in a cook, a masseuse and so on.

Smith: We had this kooky ex-Playboy model chef that cooked for us. We’d have these dinners at night, and some of Rick’s friends would come by — always laughter and fun all around.

Flea: Just play music. That had always been the dream. And this was the most music-playing situation. Untethered to responsibility of the real world. It was more than I ever could have imagined and probably the peak of that feeling I’ve ever had in my life.

Kiedis: We very rarely left.

Smith: We all picked out rooms to live in. I picked out one where the bathroom was always really cold. Like, weirdly cold.

Frusciante: The other rooms were bigger, but I liked the maid’s quarters.

Flea: I had this little room up towards the very top of the house. There was a mattress on the floor, a little bedside table, and that was it. I was in my temple space.

Rubin: It was our own world. We worked, ate, hiked and played a lot of pingpong.

Goetz: It was very magical, and apparently they thought it was haunted.

Bowden: The security guard thought he had experienced some sort of supernatural experience.

Flea: I was always imagining that I was hearing things at night when I was going to sleep. I remember John saying that he had distinctly heard this woman. There was a story going around that there was a female ghost.

Smith: Two guys who were like the Siskel and Ebert of the spiritual world came to see if the house was haunted. One guy had like a coat hanger and [makes wooing ghost sound]. I’m thinking this is some hokey f—ing bulls—.

Flea: We did the Ouija board, and the thing was moving around like crazy.

Smith: These Siskel and Ebert guys came into my room and they went into the bathroom and both of them were like, “Something really bad has happened in here.” And even though I thought they were hokey, that was all I needed to hear. I was like, “I’m out of here.” From then on, I slept at home. The other guys were like, “Chad is scared of the ghosts.” Partly it was that, but more I needed a break. No offense to the other guys. I’ll spend all day recording, but I don’t need to be hanging out all night.

Once settled, the quartet set a strict schedule for recording. Rubin spent his days honing the songs with the band members, who were eager to absorb the feedback. Stylistically, they were ready to temper the rap-funk, slap-bass sound that had earned them their first fans.

Frusciante: I was simplifying what I was doing, and then Flea got excited about that and started simplifying what he was doing.

Flea: It had to do with the kind of stuff that John was writing and having a complete belief in him and wanting to serve what he was doing. That didn’t always require a wild bass line.

Rubin: The band started with a format defining the Chili Pepper sound. That served them well. By the time of ‘Blood Sugar,’ they were ready to expand the palate.

They were also young men enjoying the experiences that come with popularity — among them, a Hollywood groupie who would pleasure the three Peppers living in the mansion, as Kiedis chronicled in his 2004 memoir “Scar Tissue.”

Kiedis: Sex was an ongoing learning experience. I wasn’t necessarily completely healthy with my sexual behavior. I was never abusive or terribly selfish, but I didn’t understand clearly the responsibility of being extra thoughtful about the sex life. I was learning on the job. I still am.

Flea: I was single, and I was trying to get laid, and I was trying to make a good record.

Kiedis: The Red Hot Chili Peppers were always proud of love and human sexuality, and we wanted to celebrate that from the very beginning without being in any way analytical or trying to be correct or incorrect. We just wanted to show that there’s a beautiful relationship to human sexual energy and music and dancing and having fun and feeling free and being a kid.

The lyrics to “I Could Have Lied” were inspired by Kiedis’ crush on singer Sinead O’Connor, whose 1990 album “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got” had propelled her to international fame.

Kiedis: I knew that she would hear it because I left her a cassette of that song on her doorstep. That relationship was in its infancy — it was more of a friendship — and I think in my mind I was like, “Oh, this is about to get hot and heavy.” In her mind, obviously, it was not. She ended up leaving town without so much as a goodbye.

I love playing that song now. It makes me feel hurt in a good way.

A standout during the sessions was “Breaking the Girl,” a song about a breakup that resulted in one of the album’s most memorable moments.

Flea: John had been studying some Duke Ellington chords, and he was like, “The first four or five chords of this Ellington song go really well together.” I think the first four chords ended up being either the verse or chorus of “Breaking the Girl.”

Frusciante: “Breaking the Girl” was one of the first songs that I wrote before we even started rehearsing for the record, and everybody was very excited right off the bat.

Kiedis: I was in a relationship that had gone sour. Horribly, horribly sour. For whatever reason, maybe because of my own inherent mental illness, I’ve often been attracted to women who also have a very strong and beautiful mental dysfunction. [“Breaking the Girl”] was a moment where I realized I’m jumping into these relationships and taking everything I want, but the end result is there’s going to be pain — in that case, more for her than for me.

Though it marked a stylistic shift, the enthusiasm for “Under the Bridge,” a contemplative song about loneliness in Los Angeles, was immediate.

Kiedis: Rick was over at my house in Beachwood Canyon and he’s like, “Tell me some of the ideas you have,” and I showed him some half-written stuff and some completely written stuff. And he’s like, “Cool, cool. Anything else? What’s this on the back of this very last page?” And I was like, “Ah, that’s nothing. I was feeling a little out of sorts in early sobriety,” and he’s like, “Well, how does this go?” I’m sure I sang it completely out of tune. And he was like, “I love that. Let’s go to work on this.”

Rubin: I came across the poem in one of Anthony’s notebooks and asked what it was. He said it wasn’t for the Chili Peppers. I asked why, and he said that’s not what they do. That started the conversation about removing any limitations and becoming more experimental with what the band was capable of.

Kiedis: It’s a very quiet, intimate song. And oddly enough, as poorly as I must’ve sang it on that day, Chad and Flea were like, “Oh, hell yes. We love this. This is our new song.”

Baker: Records like “Under the Bridge” and “Give It Away” had their own life. It wasn’t just pandering to what people were used to hearing. Not only were they successful on MTV, but they showed a side of the band that it hadn’t exhibited previous to those videos.

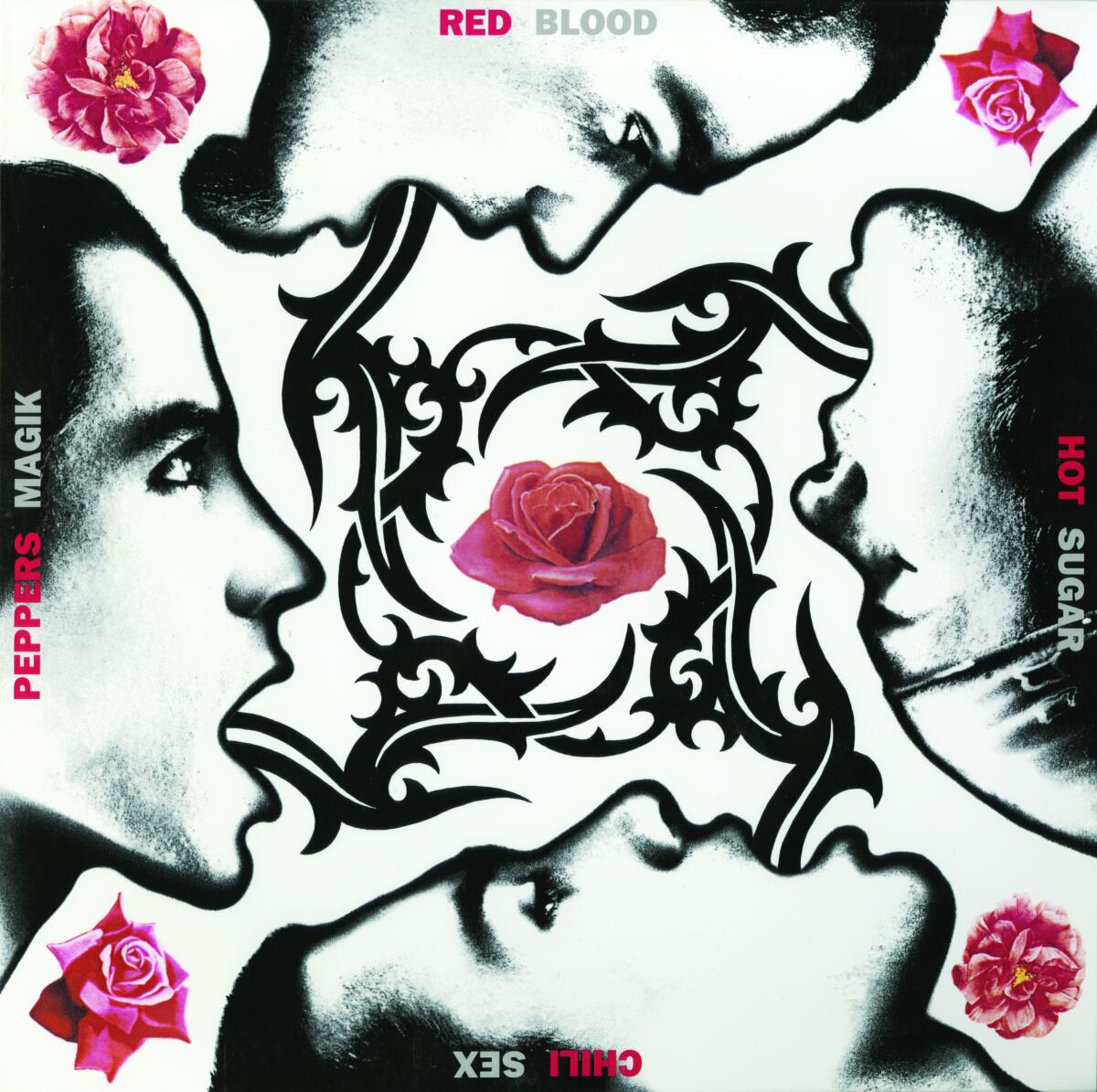

Released the same day as A Tribe Called Quest’s “The Low End Theory” and Nirvana’s “Nevermind,” “Blood Sugar Sex Magik” debuted at No. 14 on the Billboard album chart. The album hovered in the top 50 for six months and peaked at No. 3 on May 16, 1992. Dutch tattoo artist Hendrikus “Henk” Schiffmacher watched in wonder from his shop in Amsterdam. His hand played a major role in the cover of “Blood Sugar Sex Magik”: He drew the swirling tongues exiting each member’s mouth.

Schiffmacher: We knew each other from the very beginning of the Chili Peppers. Somebody said that you have to see this band from the U.S. called the Red Hot Chili Peppers. I didn’t expect that to be a group of children, you know?

Flea: We really loved Man Ray. So we asked [director] Gus Van Sant to take pictures and to get them solarized. The rest of the album design was really Anthony and Henk.

Schiffmacher: I went to the States later. Tower Records was still there, this beautiful store on Sunset. The store had a huge billboard of the album outside. Oh, my God, I got a boner from that thing.

In the wake of the album’s release, the band hit the road for an extensive fall tour, including shows with opener Smashing Pumpkins. It closed the year with a string of West Coast dates with a pair of supporting acts who were just starting to break: Pearl Jam and Nirvana.

Kiedis: I got a pre-release cassette of “Nevermind,” and I remember driving all over the city listening to that record as loud as I could and telling anyone who’d listen,”You gotta hear this band.”

Flea: Between the time we asked Nirvana to play the shows and when the shows came around, their lives had completely changed. They didn’t want to do [the tour]. I remember feeling bad about that. I think they were overwhelmed.

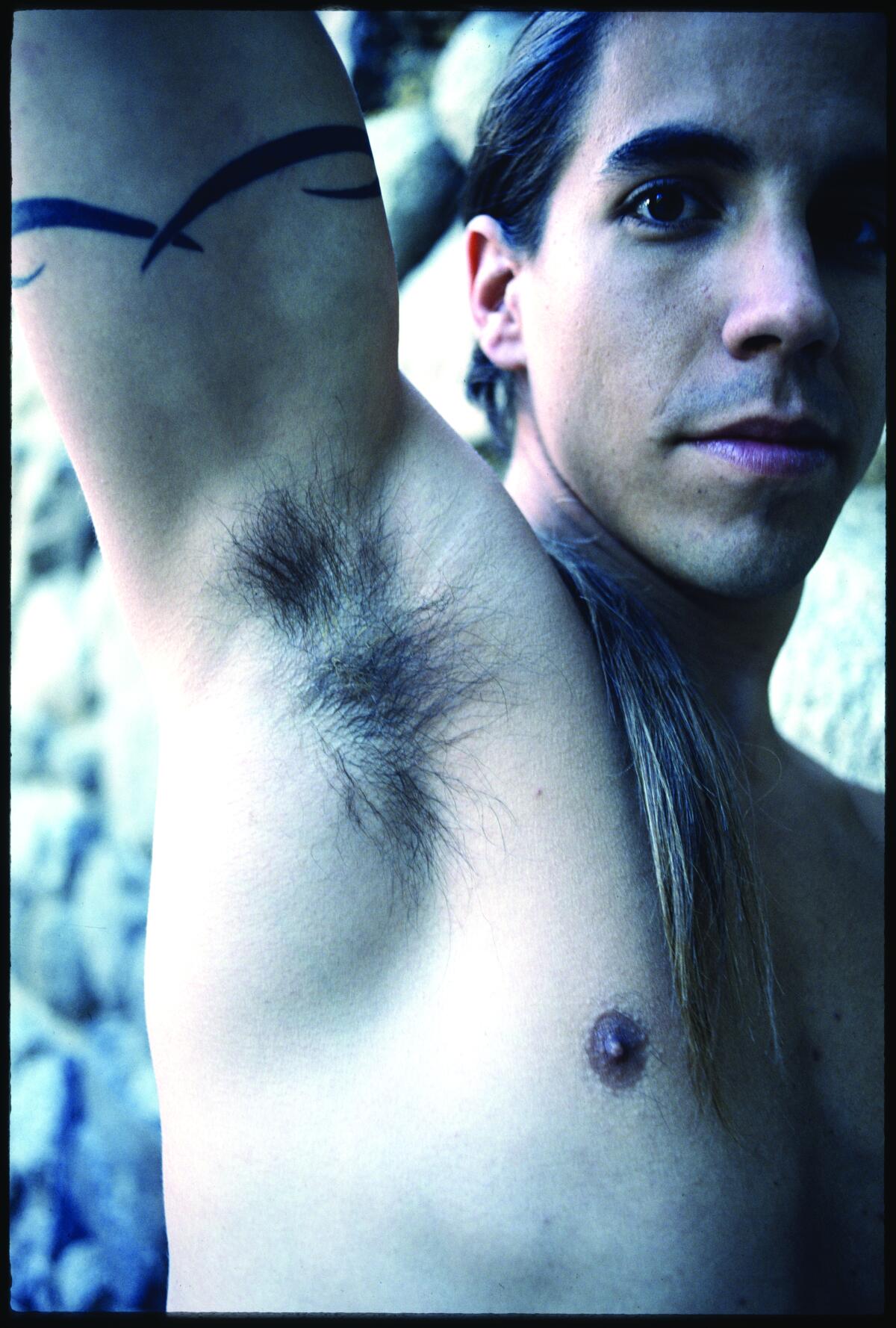

They weren’t the only ones. Frusciante wasn’t coping well with being a touring member of the Chili Peppers.

Frusciante: I had a very strong feeling that I should quit the band before I even moved out of the house. I knew that if I tried to go into that world of touring again, I was going to lose all that creative space that I built while we were writing and recording. Yet I lacked the courage to give this thing up.

Smith: It was in Japan that John quit [May 7, 1992]. Literally like hours before a show he called our manager and was like, “I can’t do this anymore. I’ve got to go home right now.”

Goetz: The tour manager called me at the hotel and said, “You’ve got to get here. John won’t go on.” I drove over there and said, “You’ve got to go on. We’re here.” So he went on. When the show was over, we put him on the plane back home.

Kiedis: That’s an absolutely reasonable response to becoming famous. Not everyone has to go, “Woo-hoo, I’m famous now. I can do whatever I want.” Some people are going to go, “Oh, no. This hurts. It doesn’t feel good. It’s awkward, it’s uncomfortable and yucky.”

Frusciante nearly died from his addictions, and as he struggled, the band replaced him with former Jane’s Addiction guitarist Dave Navarro. Infected with abscesses and rotting teeth, Frusciante hit rock bottom. Meanwhile, the Red Hot Chili Peppers were on the verge of implosion. Navarro wasn’t a good fit.

As a last-ditch effort, they offered Frusciante, who had sought treatment, his old job back. He accepted and the result was 1999’s “Californication.” Though he left the Peppers in 2009 to work on his electronic music, in 2019 the band announced that, once again, Frusciante was back — and involved in the making of its forthcoming Rubin-produced album. It will be the band’s 12th full-length.

Frusciante: When I joined the band for “Californication,” those guys were the only people in the world who believed in me. I had very few friends, and most of them just felt sorry for me. They didn’t think that I could ever amount to anything. Flea and Anthony knew what I had inside me, as they did when I first joined the band.

Flea: Being in a band can be really hard. Those relationships, those dynamics, are hard. We all have egos. We’re all fragile. But we created a magic world for ourselves.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.