In April, actor Dwayne Johnson, dressed in a tight red V-neck, walked to the Colosseum stage at Las Vegas’ Caesars Palace to gleeful applause from thousands of movie theater operators.

The first audience member he called out was Adam Aron, chief executive of AMC Theatres.

“The silverback himself is in the house,” said Johnson, there to promote his upcoming DC superhero movie “Black Adam.” “What’s up, Adam? Why do they call you the silverback?”

“Because I’m the king of the gorillas,” Aron said.

“All right, well, don’t mess with Adam,” Johnson said.

Those not familiar with so-called meme-stock lingo may have been puzzled by talk of gorillas at CinemaCon, the annual confab where studios and celebrities preview blockbusters for the world’s multiplex owners.

Some attendees probably weren’t aware of “meme stocks,” a term for companies — like AMC and GameStop — whose shares trade at sky-high prices based not on normal metrics such as profitability but on the enthusiasm of legions of extremely online amateur stock traders.

The back-and-forth showcased Aron’s unique celebrity status in the movie business and online investor culture, as the head of the world’s biggest cinema chain at a time when the theater industry faces existential questions. The term “gorillas” — or “apes” — refers to the investors who have championed AMC for a year and a half.

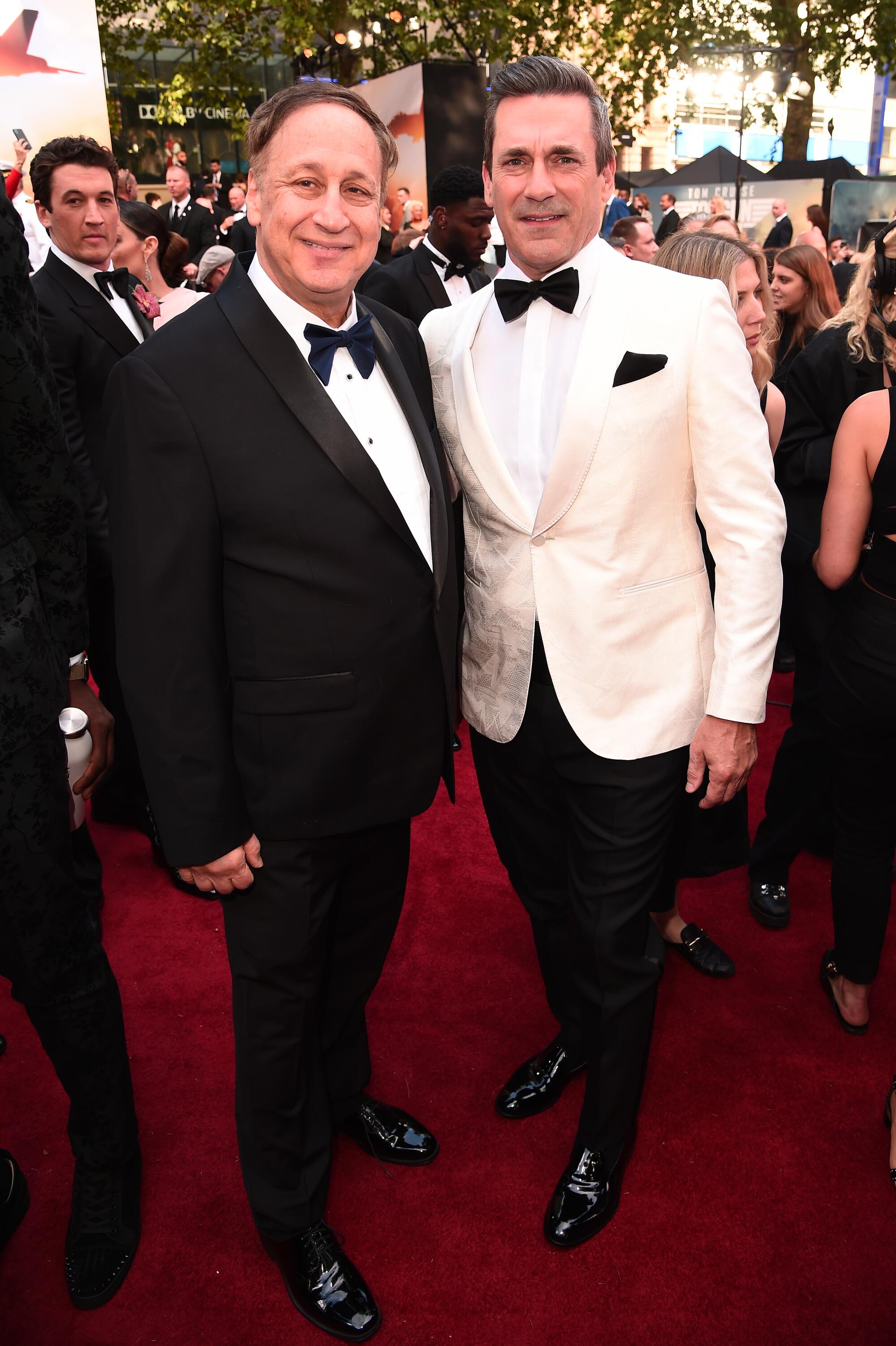

To traders who’ve obsessed over Aron’s every move, he’s become a folk hero. Last month, the affable 67-year-old executive was greeted by a couple of investors on the streets of London, who recognized him despite his being fully masked.

Since the stock market frenzy that buoyed AMC in early 2021, Aron has been inundated with thousands of suggestions and comments a day, largely from Twitter. Some of Aron’s most surprising ideas come from retail investors’ tweets, which he reads for about an hour daily. Will you issue NFTs? Yes! Will you accept Shiba Inu cryptocurrency in exchange for tickets? Why not!

“I think it’s important to read these things, because it gives me a very good finger on the pulse and a sense of what is on the minds of the people who own AMC,” Aron said. “And remember, they do own our company, and what they think matters.”

But in Hollywood, Aron is a polarizing figure.

To some, he’s a savvy operator who came into the theater business as an outsider but saved AMC from almost certain bankruptcy during the pandemic. To critics, though, his penchant for P.T. Barnum-esque showmanship is wearing thin. They say his outlandish moves — such as investing in a struggling Nevada gold mine and the retail popcorn business — do more to boost AMC’s share price and his own portfolio than to help the movie business recover.

It’s the movies, stupid.

— AMC chief executive Adam Aron

Running AMC from its headquarters in Leawood, Kan., a suburb of Kansas City, Aron speaks with a jovial, seemingly unpolished style and often cracks jokes.

He quoted Winston Churchill on a conference call to discuss earnings (“We shall fight on the beaches!”) and recently paraphrased Bill Clinton campaign strategist James Carville to explain what would bring people back to theaters (“It’s the movies, stupid,” a twist on Carville’s “It’s the economy, stupid”).

At one CinemaCon, he paused an interview in his hotel suite to retrieve his anxious grand-dog — a small dachshund — from another room. During another, he mused aloud about allowing patrons to text in dedicated auditoriums. He quickly withdrew the idea after a fierce backlash.

“I sometimes wonder if he’s just expressing a stream of consciousness, or if he’s looking to create some kind of provocative response to break with the status quo,” said Mike Ribero, a longtime marketing executive who was a contemporary of Aron’s in travel and hospitality. “I really do think that the industry needs somebody like Adam to start shaking things up.”

Aron’s marketing skill and eye for the limelight, developed over decades in hotels, airlines and sports, turned out to be well-suited for courting the meme-stock crowd.

Are movie theaters back for real this time?

In a rare display of showiness for a cinema executive, in January Aron rolled down Pasadena’s Colorado Boulevard on an AMC Rose Parade float with a 1-ton LED video screen to advertise upcoming movies. Aron waved to the crowd sitting on one of AMC’s recliner chairs.

This followed another Aron innovation: AMC’s $30-million-plus advertising campaign, which stars actress Nicole Kidman extolling the wonders of the big screen. Previously, cinemas had simply advertised movies and showtimes. Aron wanted to promote AMC itself.

The resulting commercial, which ran on TV and before every AMC screening, achieved cult fandom. Fans recited Kidman’s dramatic lines and put them on T-shirts (“Somehow, heartbreak feels good in a place like this.”) When theaters started replacing the 60-second ad with a shorter version, fans circulated a petition to protest.

Admirers say Aron’s unexpected moves are what have made him successful.

“Adam has done an amazing job of steering the company through the pandemic,” said Peter Levinsohn, vice chairman and chief distribution officer of Comcast Corp.’s Universal Filmed Entertainment Group. “Not coming from this industry, he’s done a great job of trying to stay outside the box and to be innovative.”

But some of Aron’s actions have given even enthusiastic investors pause. Starting late last year, he sold roughly $43 million in stock as part of what he described as “prudent estate planning.” Some shareholders, who’ve committed to a “hold the line” ethos, were taken aback.

Some critics suggested that Aron, having set himself financially, has taken his eye off the ball when the health of the theatrical experience is far from assured. Was Aron in the movie theater business or the stock promotion business?

Richard Greenfield, an analyst at LightShed Partners and an AMC skeptic, says Aron’s antics are distracting investors from the fundamental challenges, including continued losses, $5.5 billion in debt and an uneven box office recovery.

“Instead of paying down debt, he’s investing in a mining company,” Greenfield said, who has had a price target of 1 cent on AMC’s stock since March 2021, when the stock was priced at $10.50. The stock now trades at about $12 a share. “He’s taking investor resources and trying to promote a popcorn business and wasting energy on a crypto coin scheme at his theaters.”

Aron says he’s no less dedicated to AMC’s recovery since the stock sales, noting his interest in 2.9 million shares, including stock to be issued in the future and tied to performance. He said he’d been transparent with stockholders about his intentions, forecasting his sales as far back as August and spreading them over several months. Plus, he said, it’s not in his nature to pull back from a business he’s running.

“Whenever you do anything, you’re going to pick up critics along the way, but I think we’ve got a pretty good track record of success,” Aron said. “The fact that I’ve worked hard my entire life and I’m a 24/7 guy, I wouldn’t take my eye off the ball in any case.”

More than ever, U.S.-Canada box office sales are dominated by a handful of huge studio films.

To him, expanding into things like the gold mine deal and popcorn sales is an example of going “on offense.” Same goes for a recent deal to outfit thousands of auditoriums with laser projectors. Minting NFTs for movies like “The Batman” and “Spider-Man: No Way Home” helped sell movie tickets.

And though he frequently uses the latest box office hit to refute the “naysayers” and “prophets of doom,” as he calls doubters, he acknowledges the business is not out of the woods yet. However, he says, it is going in the right direction.

“There were people in 2017 who were convinced movie theaters were at an end,” Aron said. “They were wrong. There were people in 2020 who were convinced that AMC was going to file for bankruptcy. They were wrong. There were people who laughed when we bought 22% of a gold mine. ... Maybe they were wrong again.”

A native of Abington, Pa., a Philadelphia suburb, Aron was born the youngest of three. He served as treasurer of his high school (class of 1972) before going to Harvard, where he earned his MBA. He inherited a sense of humor from his father, who ran a local advertising business.

Aron built a reputation as a marketer and a champion of loyalty programs, launching Pan Am’s first frequent flyer program. He later ran Norwegian Cruise Line and skiing destination firm Vail Resorts before joining an investor group to buy his hometown NBA team, the Philadelphia 76ers. As the basketball franchise’s CEO (“a boy’s dream,” he said), he embraced a pricing gimmick, slashing the cost of upper-level tickets in 2011 to $17.76.

In 2015, as a company he was running, Starwood Hotels & Resorts, was being sold to Marriott, he was contacted by a headhunter who was looking for someone to lead AMC. He had a connection. When raising his two sons in Glencoe, Ill., a suburb north of Chicago, his local theater was the AMC in Northbrook Court. A movie buff since youth, he watched “The Wizard of Oz” on TV with his mom every year. Early favorites included “The Odd Couple,” “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” and World War II flicks like the 1965 Frank Sinatra vehicle “Von Ryan’s Express.”

“I thought, ‘Movies! That sounds like fun,’” he said. “Right up my alley.”

Movie theaters raise prices for big movies. Streaming services create cheaper tiers. How elastic is demand for film and TV?

After being named to the job, Aron trekked to AMC’s Empire 25 in Manhattan to see J.J. Abrams’ “Star Wars: The Force Awakens.” He still enjoys going to public screenings, recently attending a double feature: “Downton Abbey: A New Era” and, for the third time, “Top Gun: Maverick.”

He would transfer his learnings about pricing and loyalty programs to AMC, where he boosted the company’s membership program, AMC Stubs, and launched a subscription service allowing three visits a week for a monthly fee.

Backed by AMC’s controlling shareholder, Chinese conglomerate Dalian Wanda Group, Aron aggressively expanded the company. Deals to acquire Carmike Cinemas and other chains made AMC the world’s biggest circuit. They also added to AMC’s debt.

When COVID-19 hit the U.S., theaters shuttered and studios delayed their biggest movies or put them on streaming services. Bankruptcy seemed assured for AMC, which furloughed tens of thousands of workers.

“It didn’t matter what our debt load was,” Aron said. “We had no revenue.”

Nonetheless, Aron defied gravity. The company negotiated rent deferrals from landlords, with Aron dealing with some of the largest property owners directly, and raised more than $1 billion in debt and equity between April and November of 2020. In January 2021, the company announced $917 million in fresh capital and Aron declared that any talk of imminent bankruptcy was “completely off the table.”

That kicked off a wild stock market ride. Enter the gorillas.

Amateur investors poured into AMC, fueled by posts on Reddit financial forums. The share price soared from $5 to nearly $20 in a day and eventually topped $70. Mirroring the GameStop rally, investors embraced AMC for nostalgia, plus a mission to squeeze short sellers and “save” theaters.

“The stock has been completely dislocated from normal valuation metrics,” said MKM Partners analyst Eric Handler.

He was willing to play our game and kind of get into our culture, which I think was just very highly respected.

— Matt Kohrs, AMC shareholder and financial YouTuber

While other CEOs kept retail traders at arm’s length, Aron became a meme-stock mascot. That May, Aron announced he and AMC would each donate $50,000 to the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund, a sly salute to the traders.

“He was willing to play our game and kind of get into our culture, which I think was just very highly respected,” said Matt Kohrs, an AMC shareholder and financial YouTuber.

Playing nice paid off. AMC raised $1.25 billion in new equity capital by selling shares. China’s Wanda cashed out, leaving AMC’s ownership with more than 4 million shareholders. The company’s newfound liquidity gave Aron the confidence to pick up new theater leases, including defunct Pacific Theatres locations in Los Angeles at the Grove and Americana at Brand.

The Reddit story had a dark side. Skeptical analysts got pummeled with disparaging comments on social media. Some of the harassment has been leveled at Aron himself. “While most [feedback] comes in constructively, some comes in with hostility or laced with threats,” he said on a call with investors.

Aron, who rarely tweeted before the meme-stock frenzy, was not immune to social media landmines.

In December, after a Canadian court hit Regal owner Cineworld with about $1 billion in damages for scrapping a merger with Canadian chain Cineplex, Aron tweeted, “Anything distracting or destabilizing our biggest competitor brings opportunity to AMC.” He accompanied the tweet with a picture showing stacks of cash.

Some thought the tweet hilarious. Others were not amused, seeing the tweet as a cheap shot against a competitor. Aron, who’d thought he was simply stating the obvious, called Cineworld CEO Mooky Greidinger to apologize. The two executives are “good friends,” Aron said. Through a spokesperson, Greidinger declined to comment.

Analysts were even more baffled at AMC’s 22% investment in Hycroft Mining Holding Corp., a precious metal operation in Winnemucca, Nev. Aron announced the deal on Twitter with a photo of himself wearing a hard hat with the firm’s CEO.

There was logic to the deal. It just had nothing to do with theaters.

Aron saw an opportunity to lend AMC’s meme-stock expertise to another business to stave off collapse. Hycroft’s shares rose as investors followed AMC’s lead. The mining company raised $138.6 million through an at-the-market financing round, and AMC’s investment soared in value.

As for AMC’s future, Aron knows it depends on the film business’ broader recovery. Box office attendance, which had been declining before the pandemic, has picked up steam, though not as quickly as the industry had hoped.

“Spider-Man: No Way Home,” “The Batman,” “Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness” and “Top Gun: Maverick” have put up huge numbers. Nonetheless, total box office sales are down about 35% this year compared with the same period in 2019.

But Aron remains ever optimistic. He projects that AMC will return to profitability and that momentum continues throughout the year with movies like “Thor: Love and Thunder” and “Avatar: The Way of Water.”

“All these big movies that are coming are going to drive a stake in the heart of the naysayers and the doomsday fortune tellers that are all somehow convinced that streaming was going to make theatrical exhibition an anachronism,” Aron said. “Far from it.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.