Hollywood crew workers are poised to strike. What’s behind the labor unrest

Sharron Enriquez, a veteran script supervisor who over the last four decades has worked on productions including “The Queen’s Gambit,” “Mank” and three “Pirates of the Caribbean” films, has had a front-row seat to what she views as the steady erosion of working conditions that accelerated during the pandemic.

The long hours without breaks, the shorter turnaround times and the lack of sleep spurred Enriquez to call it a day.

After finishing a production in Boston in August where the 66-year-old worked 12-hour days on a 10-week shoot and rarely broke for lunch, Enriquez realized she was done.

“I reached a breaking point,” Enriquez said. “I was starting to lose my temper and have less patience.”

Enriquez’s sentiments are shared widely among the 60,000 film and TV industry members of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, which includes costumers, makeup artists, camera operators, set builders and writers’ assistants.

For the first time in its 128-year history, the usually acquiescent union voted overwhelmingly to support a nationwide strike if no deal is reached with the studios. The last time crews staged a major strike was in 1945 in the walkout known as “Hollywood’s Bloody Friday.”

By threatening to strike for better pay, hours and working conditions, film and TV workers are taking a stand for many who believe our work culture is broken.

The union is seeking improved pay, especially for streaming productions; more rest periods to reduce long hours of filming; and higher contributions to the union’s health and pension plans.

“I don’t think anyone wants a strike, but everyone wants a fair contract,” said Michael Miller, IATSE vice president and director of motion picture and television production, who is on its negotiating team. “The studios have not put us in this position before. It’s surprising for us because many of our core issues that they refuse to address shouldn’t cost them a penny.”

The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents the major studios, declined to comment. But the group has previously disputed the union’s claims, saying it has offered to increase rates for the lowest-paid workers and for certain types of streaming productions as well as to cover a projected health and pension deficit.

A walkout would halt production nationwide, upending one of Southern California’s cornerstone industries and hobbling major studios’ attempts to catch up on productions delayed by the pandemic and meet urgent demand to feed new streaming platforms.

The conflict has exposed a widening divide between A-listers or star filmmakers and the technicians who work behind the scenes on film sets. While the runaway success of new streaming platforms through the pandemic has driven up the stocks of many media conglomerates, fueling multimillion-dollar pay packages for chief executives, the benefits have not trickled down to crews, union officials say.

“If you want people to stay and have families and have a middle class in the industry, you need to make it viable for people to do that,” said Kevin Klowden, executive director of the Milken Institute’s Center for Regional Economics and California Center. “And there’s been a huge amount of pressure on the middle class in Hollywood.”

One of the biggest beefs among film set workers has been grueling hours and lack of breaks between shoots, a long-standing problem that has been exacerbated by a race to make up for lost time caused by pandemic shutdowns. A New York set lighting technician recently launched an Instagram page highlighting the safety hazards caused by long hours on set.

Geneva Nash-Morgan is a longtime Hollywood makeup artist who has worked for such stars as Stevie Wonder and Spike Lee, and on big budget movies including 20th Century Fox’s “Planet of the Apes” and Walt Disney’s “Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl.”

The 63-year-old recently finished work on an HBO Max comedy, on which she said 12- to 14-hour days were the norm.

Although Nash-Morgan said she enjoyed working on the show, she found the hours brutal. A typical day, she said, would begin at 4 a.m. to ready actors for their 7 a.m. shoot, and continue until 7 p.m. or 8 p.m.

Actors get a minimum of 12 hours’ rest between shoot days — so-called turnaround time — and at least 54 hours of rest on weekends. But that’s not the case for Nash-Morgan and other crew members, who have no union-mandated weekend rest time.

Nash-Morgan said she routinely would arrive at her trailer on Fridays at 11 a.m. and return home as late as 5 a.m. Saturday morning in what crews call “Fraturdays.”

Earlier this month, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees voted in support of waging a strike if the union couldn’t agree to a new contract.

The extra hours bring in overtime pay, and many crew members are grateful to be working after thousands lost jobs during the pandemic. But many say the long hours come at a cost to personal health and safety.

Nash-Morgan said she was so exhausted at times she would bump into objects and get bruises on her body.

“You have to have a mind-set to be able to have the stamina to get to the end of the week,” Nash-Morgan said.

Additionally, many workers complain that they struggle to make ends meet, especially living in Los Angeles, and that attempts to negotiate their rates are rebuffed, even as they watch productions spending lavishly on sets and, most recently, on COVID-19 safety protocols.

Art department coordinator Marisa Shipley is vice president of Local 871, which represents some of the lowest-paid crafts. She joined the union five years ago after working with her father, who built sets for commercials.

The 33-year-old, who has worked on Netflix’s “Grace and Frankie,” among other productions, said she has to fight for an increase over her union local’s minimum hourly rate of $16.82 each time she takes on a new job. California’s minimum wage is $14 an hour.

“It’s really, really exhausting and demoralizing to have to negotiate for and prove your worth on every single project,” Shipley said. “I had a [unit production manager] say to me one time, ‘Well, I work for scale,’ and I said, ‘Well, I’d work for your scale too.’”

Colby Bachiller, a 29-year-old script coordinator, shares a similar story.

Bachiller said that when she was asked to return for a second season on a network series this year, she took the opportunity to negotiate.

But when the Philippines native, who had moved to Los Angeles from Georgia in 2019, asked for a 30-cent hourly increase over the $19.70 minimum rate the studio was paying, she was rebuffed.

“The studio rep kept saying, ‘No, I’m sorry, we can’t go above, and if you feel that you’ll have to take another job, then please let me know by Monday,’” Bachiller said. “I had already cut back to eating one meal a day. What else can I do other than get rid of my dog and cat or move back home to Georgia? I was humiliated.”

Another point of friction involves the union’s health and pension benefits.

In previous bargaining rounds, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers has increased the number of hours of work needed for crews to qualify for benefits. Now, the studios are seeking to again increase the hours to qualify for the pension plan, in exchange for covering a forecast $400-million deficit in the union health and pension plans.

The concern is that the change will make it harder for more crew workers to qualify for benefits at a time when many are still struggling to recover from losses caused by the pandemic-induced shutdowns.

The union’s health and pension plans have come under strain as streaming has taken over the television industry. Unlike actors who get residual checks, crews depend on residuals — the fees generated from reruns — to fund the IATSE’s health and pension plans. But streaming platforms pay lower residual rates than traditional broadcast television.

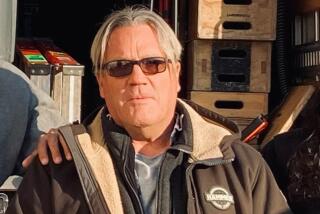

Charles Randolph, 52, a Los Angeles-based on-set dresser and member of Local 44 who has worked on some of TV’s biggest shows including AMC’s “Mad Men,” is worried about working enough hours to keep his benefits.

“They’ve been pushing those numbers higher and higher over the last couple of contract negotiations,” Randolph said. “Someone who has been in 20 years ... is going to have to work crazy hours in order to get healthcare even though he’s put 20 years of money into the system. And copays are going up, it’s just kind of insane.”

At 19, Randolph got his first break as a production assistant on the show “In Living Color.” And by his mid-30s he joined IATSE Local 44, enabling him to secure multiple jobs, make more than six figures a year and access union benefits.

In a business where jobs can be sporadic, Randolph has to work more than 400 hours every six months to keep his health and pension coverage — and make ends meet. “Otherwise we’ll have a hard time surviving in Los Angeles,” he said.

He works 13 or 14 hours a day on the Hulu miniseries “The Drop Out,” which leaves little time with his wife and son.

“I don’t see them very often during the week and then on weekends I sleep, so I see them or talk to them on Sundays,” he said. “Then when I’m over a job, we travel somewhere.”

Randolph recalled how much the business has changed since he began his career. “If you were lucky to be part of that [world], you were brought up into that world and you were taken care of. There’s not so much of that today.”

To be sure, a walkout would cause widespread hardship for workers, many of whom lost jobs during the early stages of the pandemic. But Enriquez and many union members view the strike vote as an important line in the sand.

“I love filmmaking and I love storytelling and that is still important to me,” said Enriquez, a Texas native who became a script supervisor in 1982. “We’re just trying to get some protections, so we have some rest periods and decent turnarounds and we have a weekend when we can live like normal human beings.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.