The last time it was ‘Hollywood’s Bloody Friday.’ With no deal in sight, will crews strike again?

The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), which represents some 43,000 Hollywood workers, is not known for rocking the boat.

In fact, the last time Hollywood crews staged a major walkout was during World War II.

Then, the Conference of Studio Unions was in a bitter turf war with rival IATSE, which was controlled by the Chicago Mafia, which suppressed wages and strikes in exchange for payouts from studios.

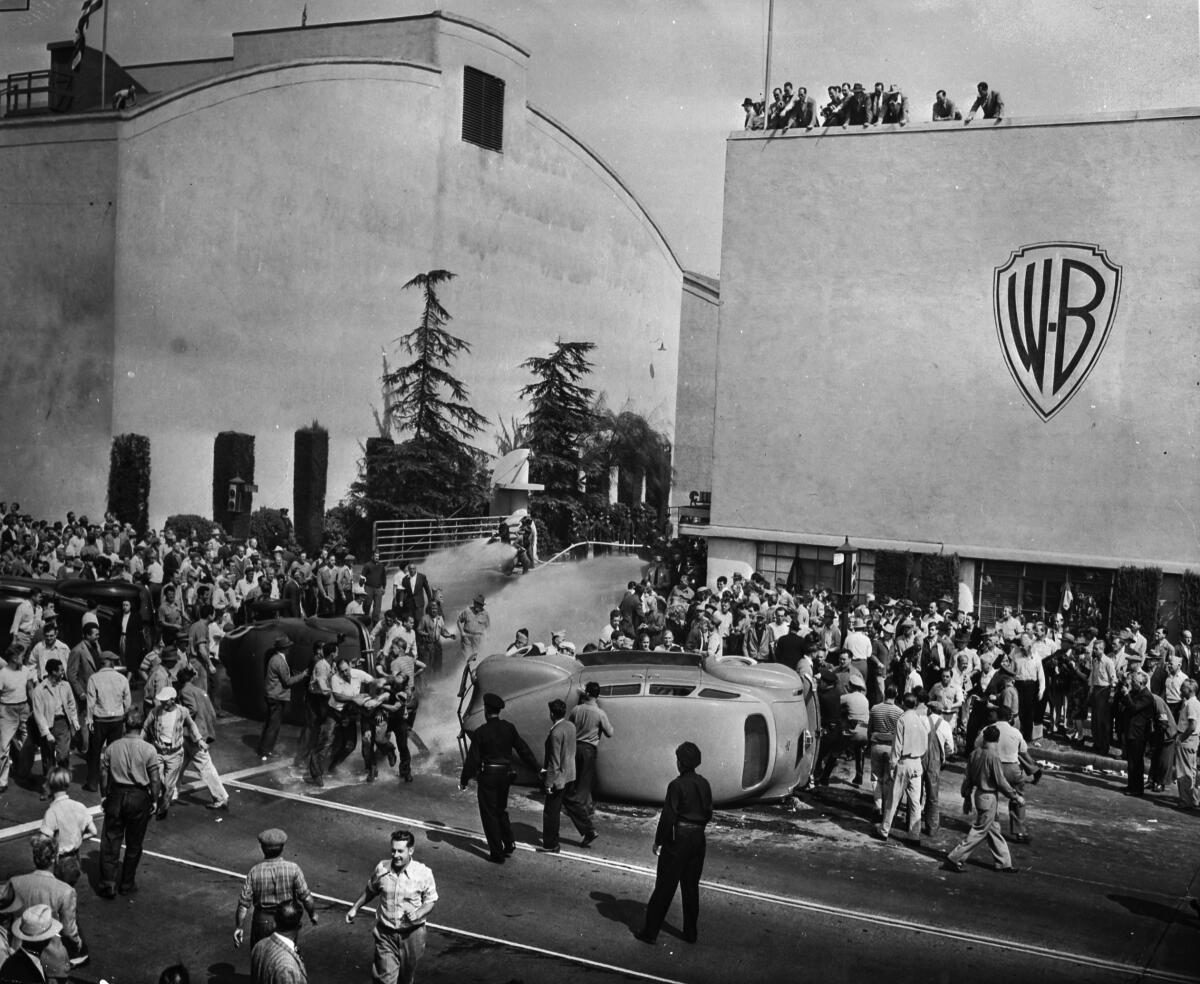

When CSU went on strike in March 1945, some IATSE members walked out in support, and violent clashes with strike breakers ensued outside the Warner Bros. Burbank studio — a day known as Hollywood’s Bloody Friday (also known as the War for Warner Bros.)

Eight decades later, once again there’s talk of a strike in below-the-line Hollywood. After months of protracted negotiations with the major studios, 13 IATSE Hollywood locals have been preparing members for a possible strike authorization vote, according to union members who were not authorized to be named.

The union has been attempting to secure a new, three-year basic agreement that covers thousands of prop makers, costumers, camera operators and other technicians who work behind the scenes on film and TV sets. But negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers have been strained and a new deadline passed Friday without a deal.

The contract originally expired July 31 and was extended through midnight Friday to allow more time for negotiations. But on Saturday, IATSE said that after two days of talks, its bargaining committee did not reach an agreement. The union said talks are continuing and told members to keep working.

The union has some leverage because the dispute comes at a time when major studios are eager to ramp up productions after last year’s hiatus caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Writers Guild of America pulled back from a possible walkout last year in part because of the production shutdown.

“There have been complaints about excessive working hours, etc., as the industry began to catch up from delayed production,” said Daniel Mitchell, professor emeritus at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. “A strike threat that would impede production would be more effective from the union perspective now than in a more normal situation.”

The labor unrest has been fueled by the confluence of the pandemic and an ebullition of streaming platforms thirsting for hot new shows and films. While media companies have seen their streaming platforms flourish, crews are feeling increased pressure from production workloads. Workers are demanding more rest time, a bigger cut from the growth in streaming and improved funding for their health and pension plans.

For their part, studios have balked at some of the demands, citing massive losses they incurred from the health crisis, which forced the cancellation or delay of numerous productions and severely limited box office returns.

Frustration has been building for years, union representatives say.

“Many of these issues IATSE has been trying to negotiate for a number of contract cycles and there hasn’t been substantive progress,” said Marisa Shipley, vice president of Local 871 and an art department coordinator.

Shipley, who declined to comment on the negotiations, added: “The pandemic changed a lot for people and contributed to bringing us to this breaking point. To see how much money producers immediately threw at COVID protocols while members continue to work in these conditions is frustrating for a lot of us. We need systemic change in the contract.”

IATSE and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which includes Warner Bros. and Netflix, declined comment. The two are subject to press blackouts during negotiations.

Although few labor watchers think a strike is likely, it’s uncertain what will happen next. Now that the contract has lapsed, the sides could still agree to another extension. In a sign of escalation, the union leadership could also ask members to authorize a possible strike to give them more leverage in talks. Locals are updating their members in coming days.

One notable change that union members are pointing to from previous negotiations is the greater dialogue between locals and crew members.

“This group is showing the most solidarity of any group of unions I’ve ever seen,” said Steven Poster, cinematographer and former president of Local 600.

Tensions boiled over on Aug. 31 after six weeks of talks when leaders from 13 Hollywood locals and IATSE President Matthew Loeb said in a statement that it was unclear whether they would be able to reach a deal with the major studios.

“Despite first person testimonials, specific examples and our multiple counter proposals in response to the employers’ stated concerns, we remain very far apart,” they wrote. “We have made some progress, but the employers have indicated they have done all they need to do.”

Since then crews have increasingly been sharing their anonymous accounts of brutal work conditions on social media and calling out excessive pay of CEOs. One post on the IA Stories Instagram page estimates that the ratio of CEO pay to that of a grip is 200 to 1, and that of an art department coordinator 536 to 1.

“We see members talking about their issues publicly across locals more than they have in the past,” Shipley said.

Among the key sticking points in negotiations is long hours. The union is seeking what it describes as reasonable amounts of time between leaving work and returning the next day, and penalties for studios that eliminate meal breaks and work crews into the weekends.

The other big issue is streaming pay. The union contends that pay rates and residuals for shows that are streamed are unfairly discounted and that crews don’t get credited pension hours on some shows.

IATSE is also asking the AMPTP for additional funding to its health and pension plans, through increased employer contributions as well as new forms of funding to offset the declining residuals from traditional distribution networks. Residuals, the fees generated from reruns, help fund the union’s health and pension plans.

“If the employers refuse to engage in substantive negotiations, refuse to change the culture by managing the workflow, and refuse to put human interests before corporate profits, the failure to reach an agreement will be their choice,” union leaders said in their Aug. 31 statement.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.