How ‘All of Us Strangers’ takes grief and loss and channels them into healing

LONDON — “All of Us Strangers,” about a lonely screenwriter named Adam who starts a relationship with a mysterious neighbor as he begins to revisit his childhood home, draws intimately from director Andrew Haigh’s own life and experiences despite being loosely adapted from Japanese novelist Taichi Yamada’s 1987 book “Strangers.” Haigh was sent the book several years ago but began writing the screenplay in the midst of the pandemic while living in L.A. and feeling distanced from his family in the UK.

“I brought a lot of my own life into it,” Haigh says, speaking in London during the London Film Festival. “I dealt with my own relationships with my parents within the story. So it took an emotional toll at the time as I was writing. But in a good, cathartic way.”

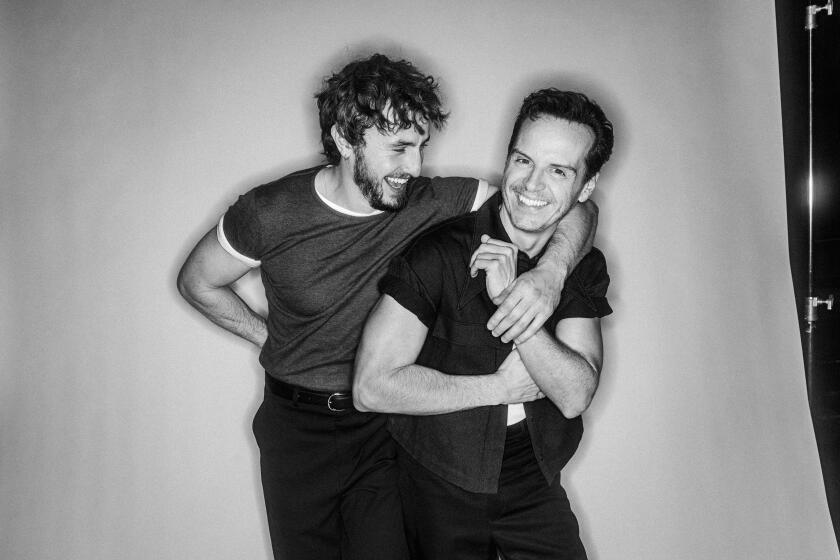

Yamada’s novel is a ghost story about a man who meets a couple who appear to be his dead parents and begins to visit them until they start depleting his life force. In Haigh’s version, Adam (Andrew Scott) visits his childhood home and reunites with his long-dead parents, played by Claire Foy and Jamie Bell. During these encounters, for which Haigh never offers an explanation, Adam comes to terms with trauma and loss. At the same time, he begins a relationship with Henry (Paul Mescal), a neighbor who appears to be the only other resident of Adam’s high-rise apartment building.

“It was that very central idea of meeting your parents again after they’ve gone,” says Haigh, whose parents are still alive. “I couldn’t get that idea out of my head. It’s such an unusual, strange idea and something that I think we all wish we could do, whether our parents are actually alive or dead. It took me some time to realize how I would turn this story into something that was for me. Because in the novel, there’s a female character, and it’s a love affair between a man and a woman. So it was about bringing elements of myself and the way that I see the world into it.”

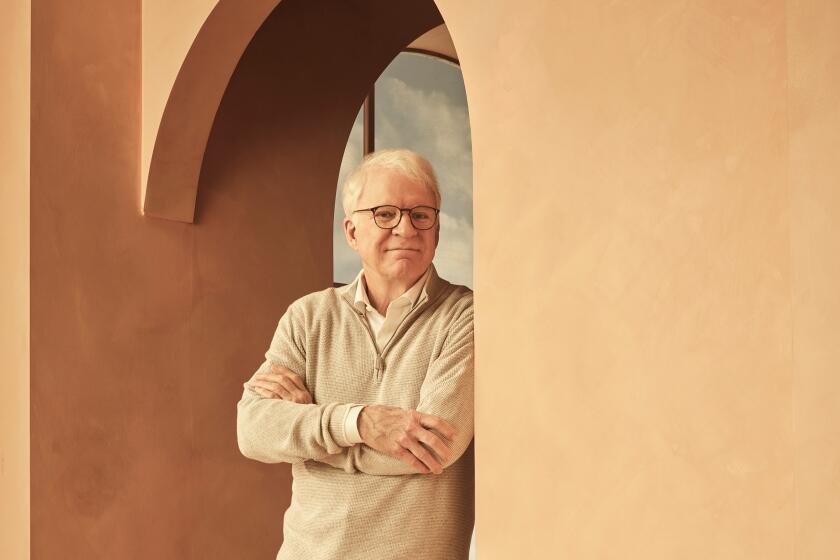

On the 2023 Envelope Actors Roundtable, Colman Domingo, Paul Giamatti, Cillian Murphy, Mark Ruffalo, Andrew Scott and Jeffrey Wright exchange views on AI, work that changed their lives and looking like other actors.

The film hinged on perfect casting, which was something Haigh knew from the beginning. He and the casting director spent a long time going through numerous possibilities but eventually landed on Scott (“Fleabag”), who hasn’t previously had the starring role in a movie. Scott instinctively understood Adam, Haigh says, and the theme of the movie, which touches on how gay men of a certain age have felt isolated since the AIDS epidemic.

“What that did to a generation of gay men and how it made them terrified of intimacy were all elements I wanted to look at,” Haigh says. “And Andrew understood that. Any gay man of that generation understands that. They understand what it’s like to be terrified to tell your parents. They understand what it was like to not be able to feel like you can exist in the world. He just got that completely. He had such a guttural, emotional effect on me. In certain scenes, I could feel what was happening to him. Sometimes I think it was even a surprise for him how much it affected him. That was beautiful to watch because it feels so real and so honest.”

“All of Us Strangers” was shot in six weeks in 2022. The scenes in the family home, which was Haigh’s actual childhood home, were completed first, and then the production moved on to the apartment scenes, done primarily on a soundstage. Everything was filmed sequentially as much as possible to help Haigh and the actors track the narrative and emotional development. Haigh hadn’t been back to the house where he grew up in years but couldn’t get it out of his mind while writing. “I couldn’t remember exactly where it was,” Haigh says of the house. “And then I found it and we knocked on their door and asked to film there. It was literally going into the past while still being very much in the present, which is what the film does. It’s about how you’re always drifting or being pulled into the past even though you’re existing in the present.”

For Haigh, the film meditates on a lot of personal ideas, but it’s ultimately about grief. It’s a subject he says fascinates him because it’s not just about the loss of a person.

“It’s about how we lose so much as we go through life,” Haigh says. “There are relationships that we have lost. We can grieve our childhood not being how we wanted it to be. We can grieve the things that we never got to say to each other. I think grief encompasses so much of our day-to-day existence. That’s what I wanted the film to be about, not specifically about someone who has lost his parents at a young age. But at the same time, I also wanted it to be about that.”

“It’d have devastated me to see somebody else play it. I don’t think I could watch it,” Paul Mescal says, contemplating his reaction if he hadn’t landed a role in the Andrew Haigh film..

There is a supernatural element to the story, particularly in the gut-punch of the ending, but Haigh doesn’t see “All of Us Strangers” as a traditional ghost story. Instead, he uses the concept of the narrative to explore these themes of grief and loss and what he calls “aloneness,” something that was magnified for many during the pandemic. He sees the ending of the film, which is open to emotional interpretation, as uplifting. For Haigh, the literal ghosts of the story represent something more significant.

“Our memories and our pasts remain, and they are the ghosts in our lives,” he says. “If I think about people who are no longer with me, they exist and I can feel them and I can almost see them and I can feel the love I had for them. It’s obvious but also profound at the same time. That strength of feeling is so intense that the love can grow even though you’ve lost that person. That, to me, is the key that unlocked something in this story.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.