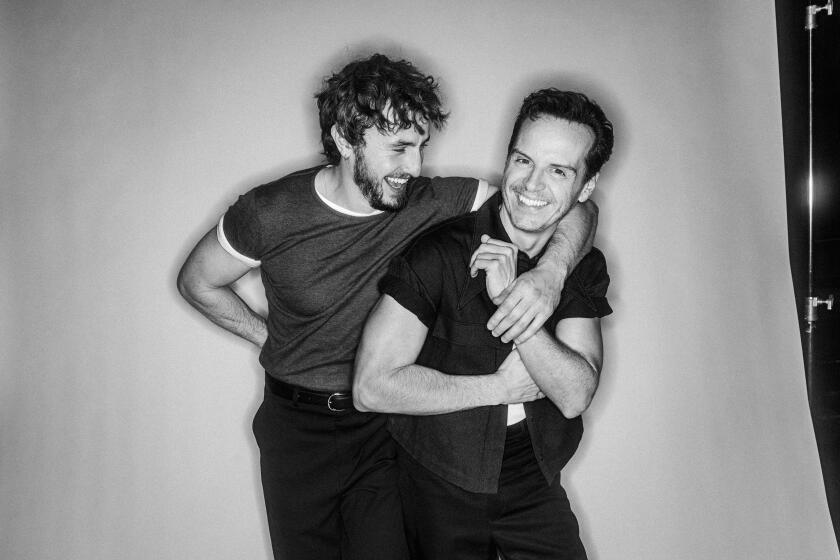

As ghostly parents, Jamie Bell and Claire Foy correct the past in ‘All of Us Strangers’

In Andrew Haigh’s intimate emotional fantasy “All of Us Strangers,” Claire Foy and Jamie Bell play parents reuniting with their grown son Adam (Andrew Scott) after a long absence — namely, their tragic deaths when Adam was a child. But don’t think of Haigh’s personal film as a ghost story. Foy and Bell certainly didn’t — they were there to create a believable mom and dad who just happen to look the same age as their son. “The fantastical or spectral element, I’m never playing any of that stuff,” says Bell, sitting next to Foy recently at the Four Seasons in L.A. “They are just people who are alive and breathing, given this wonderful opportunity to correct some things.”

Grief is already so mysterious a process that the way Haigh presents his scenario, it feels believable.

Claire Foy: What’s so difficult about grief is that you have to feel the acceptance that they’re gone. But in my experience, and those close to me, that’s not the case at all. Nor should it be. What we experience as humans is so strange. Loving people anyway is such a bizarre thing. Why is it any more strange that we’re there again? He’s able to conjure us in whatever way that is, in order to deal with something inside himself.

“It’d have devastated me to see somebody else play it. I don’t think I could watch it,” Paul Mescal says, contemplating his reaction if he hadn’t landed a role in the Andrew Haigh film..

What’s the difficulty in acting an entire marriage and parenthood in only a few scenes?

Jamie Bell: The histrionics are kind of there in the text. One of our first scenes, I say, “See, I told you it was him.”

Foy: And then you just know who they are. And in one of the final scenes, when I say, “I love you,” and you say, “I always wondered” … in that tiny little thing, you just see a whole marriage.

Bell: It’s unbelievable, right? Such a simple thing. And yet it conjures these really big, universal feelings.

When a movie is so personal for its director, and you’re shooting in his childhood home, are you talking about his past constantly?

Bell: I never felt burdened by any of that with [Andrew Haigh]. I mean, I would reach out to him and ask, “How are you doing with this?” He said he developed eczema again. He hadn’t had that since he was a kid.

Foy: It was coming out of him in a big way. But he wears it lightly. Maybe as a self-preservation thing. But maybe as recognition that he doesn’t want to burden us or make us feel like we can’t make it our own. That made it much more of an honor that someone was trusting us with a personal experience.

Can you each tell me something you love about the other’s performance?

Foy: There were moments in this film where I just could not look him in the eye, because he brought so much of himself. You have access so easily to your emotions that’s just so remarkable. But in a very masculine way, which can’t be underestimated. My favorite thing is your mustache. I didn’t want to make it all too lovey.

Bell: People like Claire, who have such a control, this ability to trust oneself and fall back on knowledge. I’ve been looking for that sense of control for years. I have such a conflicting time with it. Because it just goes “Bleaaah,” and I’m like, “Please tell me it was rolling?” Whereas when you work with actors of Claire’s caliber … the bed scene, right?

You’re referring to when Adam edges into your bedroom, and, like any mother faced with a frightened child, she invites him to crawl in between you two.

Bell: Right. And I’m passed out. I can’t see what she’s doing. I’m only listening to her voice and how touching and intimate it is. It’s all whispered, and so much is coming out. She loves having her son in bed with her and yet … I’m in awe of that sense of control.

That scene is so tricky, Claire: Andrew in those kiddie pajamas is just this edge of a sight gag, and then your exchange in bed is wonderfully touching.

Foy: I think it shows the denial we were in that I never remotely found that funny. I was like, [cheery mom voice] “Come on, darling, get in the bed!”

Bell: Usually you would mock the actor, like, “Oh you look ridiculous.” But I don’t think we ever did. I just forgot he was wearing pajamas.

Foy: That closeness, I have it with my own child. When you’ve grown someone in your own body, there’s always that feeling that they can sort of get back inside, that you can basically become one again. I know that sounds really weird. But sometimes as a mother, it’s too hard to get that distance.

“The story offered the scope for me to examine loneliness and loss, and how these experiences shape our childhood and ultimately define the adults we become,” the writer-director says in an essay.

Your characters react differently to learning their son’s gay. There’s awkwardness, but also some poignant reflecting.

Foy: I always felt like, if she’d been given the opportunity to grow into that role, the mother of a gay man, she would have been so great at it. I think what happens in her scene is as much to do with her own judgment of herself.

Bell: These are people of a certain place and time. Not too dissimilar to the time I grew up in on playgrounds and football pitches in England. It was pumped into houses, “Don’t do this, don’t show this.”

Foy: There was no visible presence.

Bell: The other thing is, they’re also children of someone. They’re hindered by whatever they’ve been through. So they’re offered an opportunity to change it. They’re still the same people. There’s no massive catharsis, no enlightenment necessarily, but they seize the opportunity. And I think that’s what’s great about them.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.