Actors, sometimes known as a “circus of the unemployable,” at least if you ask Cillian Murphy, pretty much have to do what they do. “I can’t do anything else, at all,” the “Oppenheimer” star says, laughing at his own early ambitions to become a lawyer. “It failed catastrophically and was a terrible decision. But I think it’s a need to express yourself in some way, and I’m obsessed with story. And as we become older, we think there’s certain stories I want to tell now. All the films here have something to them; they’re provocative or stimulating or they ask questions in them. That’s the long-winded way of saying there is something potentially useful for the human spirit, maybe.”

Andrew Scott agrees. “I really do believe, during the pandemic, things that helped people enormously: ‘What are you watching?’ ‘What are you reading?’ ‘What music are you listening to?’ [Art] helps people when they are at their lowest ebb,” he says. “That’s not nothing,” adds the actor, whose film “All of Us Strangers” deals with healing through connecting with those we’ve lost.

It’s not nothing, to be sure, which Colman Domingo can testify to after meeting a woman earlier this year. She “was walking me through a plantation in Georgia,” says the actor (who plays a hero of the civil rights movement fighting internal divisions in “Rustin” and the abusive Mister in “The Color Purple”). “When she found out what I do, she said, ‘You’re a storyteller.’ And she said when you get about late 50s or early 60s, you move into another season, ‘which I look forward to welcoming you to.’ I said, ‘What is that?’ She said, ‘Truth-telling season.’ ”

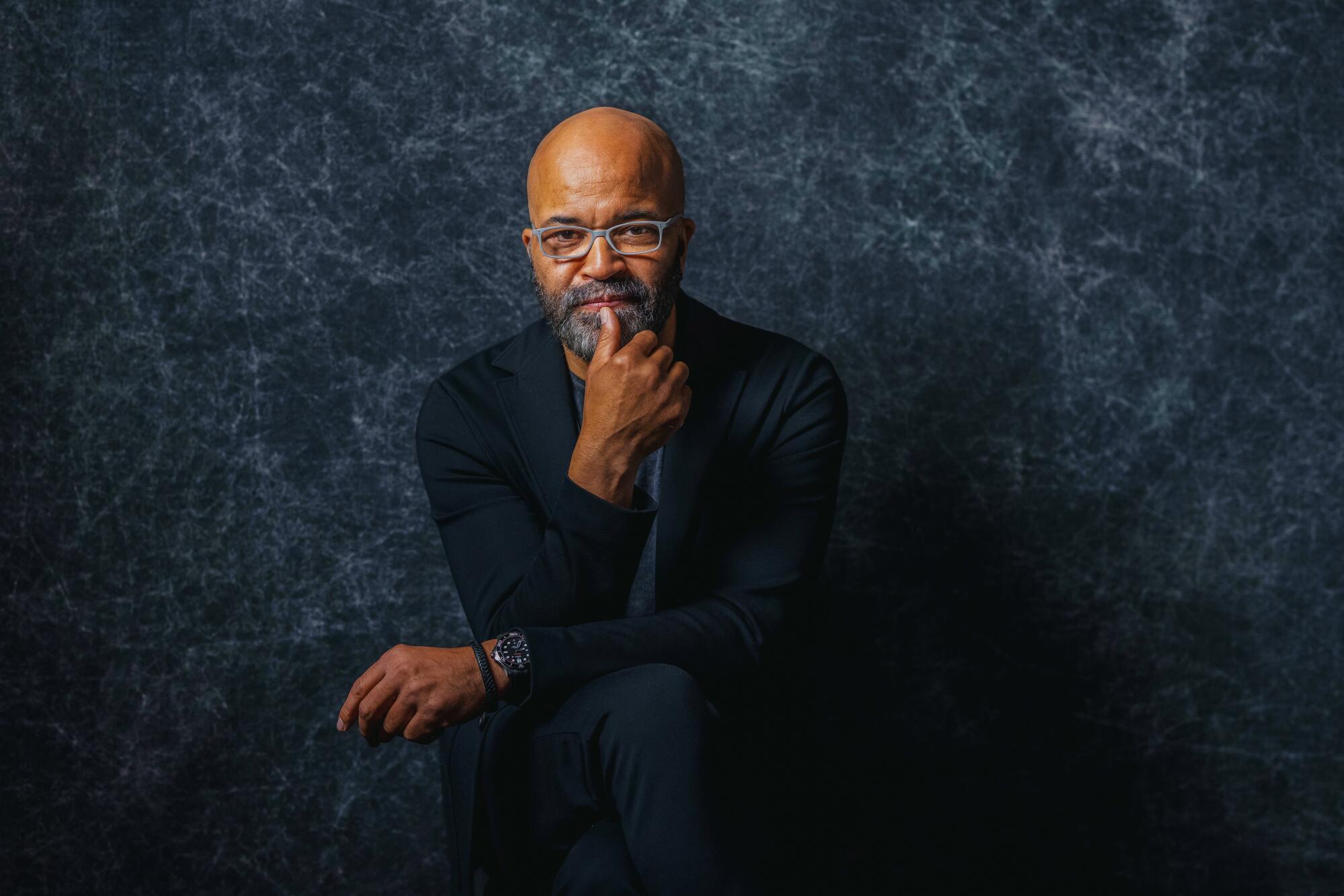

These three actors, along with Paul Giamatti, who plays a misanthropic teacher in the boarding school-set “The Holdovers”; Mark Ruffalo, a debauched cad in “Poor Things”; and Jeffrey Wright, an author driven to farcical extremes in “American Fiction” (and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. in “Rustin”), got together last month just days after the actors’ strike had ended to do some truth-telling for The Envelope Actors Roundtable. They shared their thoughts on the gravitational centers of their characters, the looming threat of artificial intelligence and how returning to work can’t be the same as it was before.

“I’m hopeful that after the strike we go back to these sets different,” Domingo says. “I think studios and artists alike, we can’t possibly think that we’re just going to pick back up and go back in. We’ve got to think, ‘What have we learned? How can we really nurture and care for each other, make sure we all feel valued and heard?’ And I think that we need to build new coalitions with our studio partners as well and have different discussions so that this doesn’t blow up again.”

These excerpts from their Nov. 19 conversation have been edited for length and clarity.

When I was looking up what projects you guys might share, I found that if you Google “Mark Ruffalo Andrew Scott” you get this weird internet opinion that you two look alike.

[Surprised laughter]

Andrew Scott: Huh, I’ll take that.

Mark Ruffalo: [Laughs] OK.

Have you ever heard that before?

Cillian Murphy: I see a movie in the works.

Ruffalo: I feel like I look a little bit like everybody.

Scott: No. No. Just me.

I don’t suppose any of you have ever been mistaken for other actors?

Paul Giamatti: I’ve been mistaken for Larry the Cable Guy. He looks a lot like me, and he’s a kind of, like, redneck comedian. I’ve been mistaken for him three times. I wonder if he’s ever been mistaken for me?

Ruffalo: Vincent D’Onofrio.

Giamatti: Oh, I could see that.

Ruffalo: I was in a grocery store and someone’s like, [whispers] “I know who you are. That episode when you got trapped in the subway and you almost died ...” “That wasn’t me.” “Oh, OK, it wasn’t you.” [as the woman, he winks conspiratorially] “No, it’s Vincent D’Onofrio.” And she’s like, “Oh, Okaaay.” She wouldn’t believe me.

The actors’ strike is over, but one of the contentious issues still out there is AI — how it’s going to be used, what actors’ rights are. Have you guys given that any thought?

Ruffalo: All I know is that Marvel and Disney have probably a thousand hours of biometric information on me that someone could put in a thumb drive and probably upload to an AI-learning piece of software and just have all that.

Jeffrey Wright: And build a new Vincent D’Onofrio.

Ruffalo: [Laughs] In our lifetime, we will probably see an AI movie star. Who doesn’t have to do roundtables. And who everybody will love.

Scott: Do you think that’s true? That people would love it?

Ruffalo: People are like, “They’re not going to be able to feel the way we do.” And I’m like, “Have you ever watched ‘Toy Story’?”

Giamatti: You’re going to have generations of people who are used to it.

Scott: But do you not think it’s something like CGI, where you go, “That’s an incredible technical achievement,” but the audience kind of go, “Mm-hmm ... I think it’s a bit AI-ish.” Like there’s some human thing [they] might not have.

Murphy: Because it’s imperfection. AI doesn’t have that built into it.

Giamatti: But maybe they are going to be able to recreate imperfection.

Wright: There’re gradations of usage. It’s already being done. We’ll be the performer version of vinyl.

Murphy: It was nice when they took [John] Lennon’s voice on that Beatles track [“Now and Then”]. The AI managed to separate it from the piano, and it was so incredible to hear his voice. So ghostly. That’s a good application.

Wright: It’s about creating automation and efficiency and carving out costs, and that often means carving out humans. To the extent that we can, as a union, protect ourselves, we must.

Murphy: It’s going to be hard to regulate it. How?

Ruffalo: No politician is going to do it. No CEO, out of the generosity of his heart, would be like, “Dudes, we’re not going to use AI. Don’t worry, we’re not going to scan you and use you forever after you’re dead.”

“Oppenheimer” is the largest grossing biopic ever. Could you have imagined that so many people would embrace it?

Murphy: Not at all. We didn’t have any clue that people would respond the way they did, and it’s just the brilliance of Chris [writer-director Christopher Nolan] — he has always presupposed that the audience are super-smart. Which they are. He never panders to them or patronizes the audience. They seem to be ready for this and wanted something that was challenging and provocative and asked questions. But yeah, it was gobsmacking that people went out in those numbers to see it. And multiple times. Which is kind of crackers.

Mark, your role in “Poor Things”: rakish, caddish, pretty much everything bad. But he has an arc and real feelings. How fun was that?

Ruffalo: It was a blast. It was all the things that you can’t do in life, like, every one you get canceled for. But also that he falls apart. That he can’t maintain that.

People start to think of you in a certain way, and it’s a kind of oppressive time right now as an artist, because there are so many eyes on you .... Everything’s under scrutiny. So to play a part that’s so against what [people] normally would think is your type, what people expect from you as your “brand” and to throw off all of that oppressive feeling was really fun and exciting to do.

What was the last time you felt pure joy being on a set?

Wright: After the martini. [Laughter]

Colman Domingo: I honestly felt pure joy on the set of “Rustin.”

Scott: Did you?

Domingo: Every day. I think [director] George C. Wolfe gave us something that was so purposeful. Our central characters and many other characters who were just filled with light and love and humanity, and that was the north star every single day. I think because of what [Bayard Rustin] was trying to do and to impart about being hopeful about this thing called America and what we can achieve together, I did feel a sense of joy every single day.

Wright: I remember one day, you started singing “This Little Light of Mine” ... things were going sideways a bit and you started singing that. And I think we all started singing it.

Domingo: We did.

Scott: That’s very nice.

Ruffalo: That’s beautiful.

Is there a role you played that changed you?

Wright: One that changed me was very early on, thankfully — I probably needed the changing — “Angels in America” on Broadway, and the film was years later, but when we did it on Broadway, that changed me in a central way.

We played one night, I think it was a benefit night, the audience was pretty much entirely gay men. And there was this sense of validation and celebration that was like nothing I’d ever experienced. I wasn’t gay; I was a jock, you know, in the locker room talking a bunch of craziness. I wasn’t the most evolved dude. But I had to address an understanding of my own sexuality and fluidity, and I had to show this side that would not necessarily have been welcomed in the locker room in high school. I was changed by that.

Murphy: When I was younger, I began to understand empathy through acting. I doubt I ever would’ve been able to learn that or activate that as a young man otherwise if I hadn’t found this. They say the definition of empathy is to walk in someone else’s shoes. That’s all we do.

[Laughter]

Giamatti: Literally.

Andrew, “All of Us Strangers” is based on a Japanese novel with evil spirits in it. Your film isn’t a horror story at all. Your writer-director, Andrew Haigh, shot it in his hometown —

Scott: He shot it in his childhood home, yeah.

Murphy: No way.

He meets the ghosts of his parents, but it doesn’t feel like a supernatural movie.

Scott: Yeah, it’s more metaphysical, isn’t it? He set the tone, really. It was a little suburban house and such a vulnerable thing to do. The crew was stomping over the place where his first little baby tooth would’ve been [coming in], where he ate his sandwiches, where he was coming out to his parents. He wore it so lightly; he’s really light, Andrew. I always thought that, from his movies, he’d be quite a serious person.

So because he was so generous with that, so vulnerable, you have a feeling like, “What can I bring to match that in some ways?” It was like a marriage to create this character [from] what his story is, and it’s sort of biographical [of Haigh]. So the attempt is to try to not do any acting, really. I just had to go back to a place — I, mercifully, feel pretty comfortable, for the most part, with who I am now, but to go back to that place where you’re 9 or 10, you don’t even quite know what the hell’s different about you, but just something is .... It’s a really beautiful idea, actually, of what would you say as a so-called adult, if you hadn’t had your parents.

Wright: What’s wonderful about the way it’s handled in the film is it becomes his inner conversations, but also their self-reflection. Because they are exactly as they were, and it’s this reconsideration of choices that I found to be really, really, beautiful.

Scott: Yeah, yeah, thank you.

Paul, your writer-director, Alexander Payne, with whom, of course, you worked in “Sideways,” has said your character in “The Holdovers” was written with you in mind. I wonder what that says he thinks of you. [Laughter]

Giamatti: That I smell like week-old haddock. [Laughter] We tried to make it for many years; he was working on it for a long time. I kept saying, “Just keep going. This is wonderful.” It never worked out, schedule-wise, because he really wanted it to be winter. He really wanted snow. And it’s beautiful. In the movie, every time it’s snowing, it’s actually snowing.

So, yes, he wrote me [a character who] smells like fish. He has hyperhidrosis, which I didn’t even know was a thing: Excessively sweaty palms. And [he has] an issue with [his] eye and stuff like that, all of which was .… He just wrote me a big gift. He is a friend of mine and was like, “I think you’ll understand this guy.” It was like a lot of things fell away and I was just drawing on things from my own life. When I saw the movie I thought, “Wow, I look like people that I didn’t even know I was manifesting — people from my past.” I didn’t even know that was happening.

Jeffrey, how far did you get into the script for “American Fiction” before calling your agent to say, “I’ve gotta make this one”?

Wright: It took me a long time to come around, because I was in a very Monk-like place, like this character [put-upon intellectual Thelonious “Monk” Ellison], where things have to fall away. The social commentary and all of that is the glow around the thing at the center, which is the story of a man who’s asked to be the caretaker of his family. And that was what really drew me in. It’s the story of this guy who, all of a sudden, all eyes are on him and he is asked to be the adult. And I had been living that for a bit, which is why it took me a while to get around to saying, “OK, let’s do it.” There had been a novel that it was based on, but I kind of just read the book of my life. [Laughs]

Ruffalo: There’s these special moments when you’re an actor where you read a piece of material and it speaks so deeply and profoundly to some sense of your own experience or something that you want, you feel a deep need to express.

Domingo: I literally auditioned for a role [in a play] about a young boy who loses his mother … lost my mother the next day.

Ruffalo: No.

Domingo: I got cast as the person who’s there to support the person who lost his mother. Every night on stage, he would look at me before he delivered a eulogy. I mean, that show truly saved my life. I needed that show at that time.

Cillian, about playing Oppenheimer … as with Rustin, there is historical material you can use – and with Adam Clayton Powell for Jeffrey. What did you find in your research that you felt like you had to bring out, so that it was a truthful portrayal?

Murphy: At the beginning, honestly, I didn’t have a clue. It was so terrifying, you know because he’s such an iconic 20th century figure and the world that we live in now is Oppenheimer’s world because of what happened in ‘45. It’s vast [what’s available] but then you’ve got to not just look at that the whole time because you get overwhelmed. You’ve got to focus on the humanity, and that was my gig, the humanity of it. A lot of people said to me, “So, how are you with quantum mechanics?” [Laughter] That is not my job. [laughs]. People dedicate their lives to that.

And the other thing was, doing an impression — that’s not one of my skill sets. I can’t do that .… Really, it was what is at stake at this point in this scene? And you know, you always know what’s at stake in the bigger picture but, what’s at stake right now between him and his wife, between him and uh, Groves and all these different characters and that was what I focused on every day. You have to do it, go at it bite by bite with those big ones, because otherwise you’re just going to be overwhelmed. A lot of it came from the outside as well. Trying to find how he walked, how he looked. Not trying to do an impression, but stealing little things. Like, he always stood with his hand on his hip in a very jaunty angle.

I think that intelligence is extremely difficult to convey on screen, but I felt like you guys conveyed genius. That this is a guy who’s seeing the world differently. Like when you’re looking at the puddles and the ripples in them — I felt, this guy’s unlocking the secrets to the universe.

Murphy: But I’ve always felt like those guys — it’s a burden. It’s not a gift. His mind is operating on a level where we could only imagine, and all of his contemporaries said that he was the most brilliant of them all. I don’t imagine that’s a happy place, because you’re thinking about things that you know, us mere mortals can’t even conceive of.

It’s difficult to be, not that I know, the smartest person in the room.

Domingo: It really is. I’ve had that problem my entire life. [Laughter]

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.