A ‘cold-blooded killer’ called Smiley haunted L.A. for 14 years. How he finally faced justice

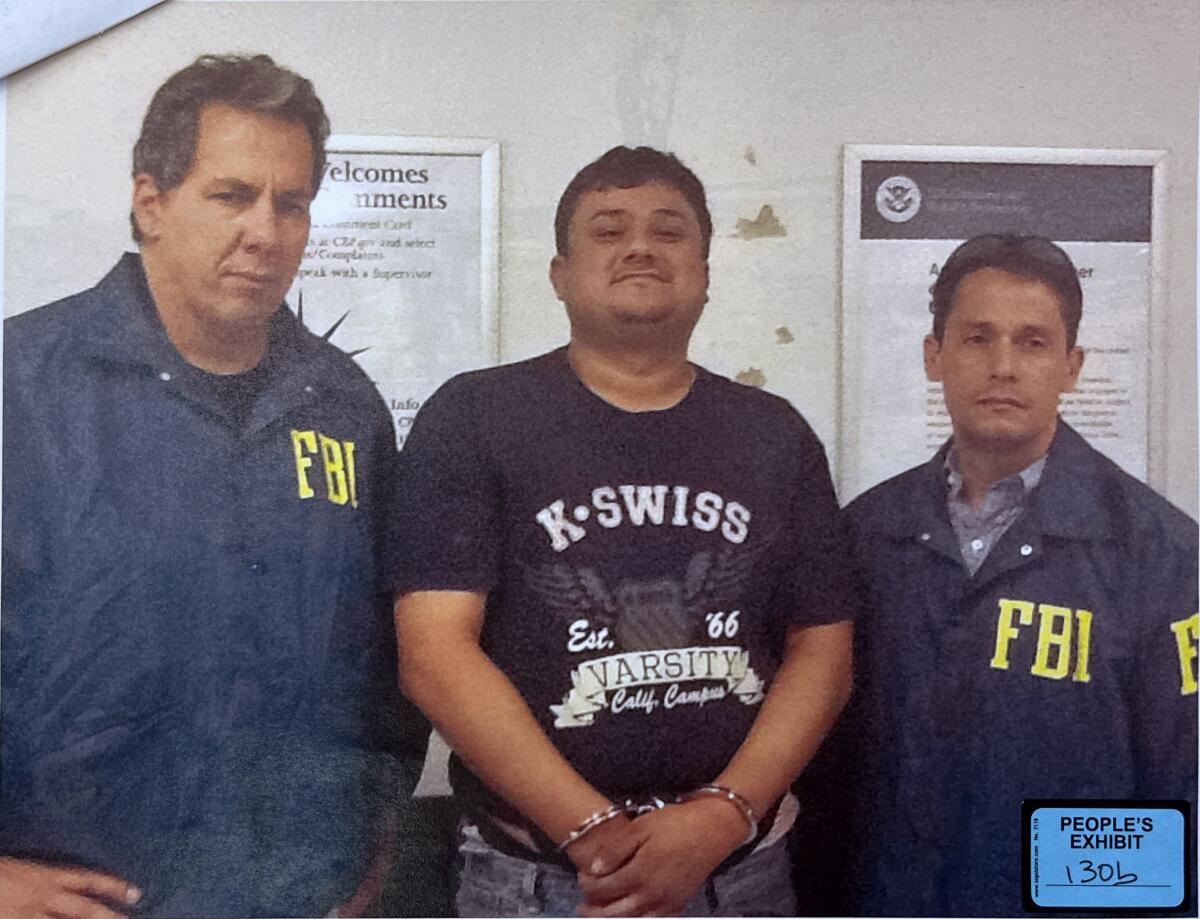

The killer nicknamed Smiley sat in the last row of an Alaska Airlines jet, barreling toward Los Angeles and his past.

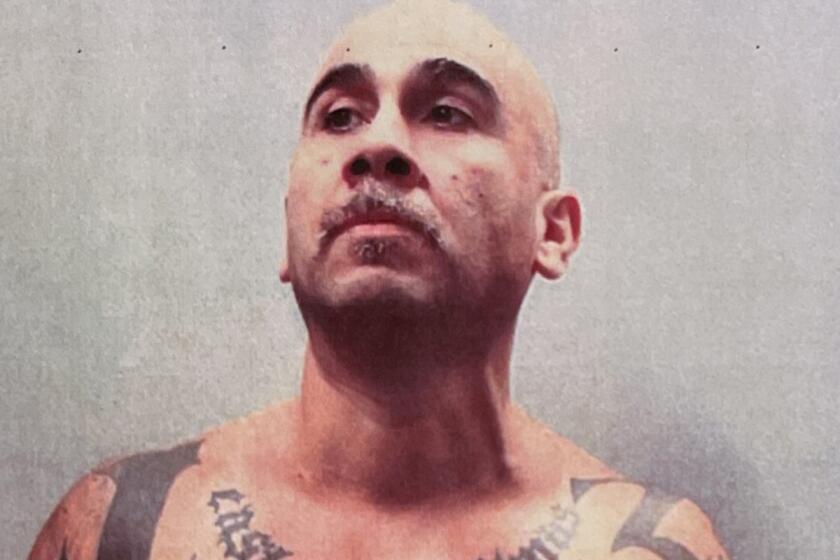

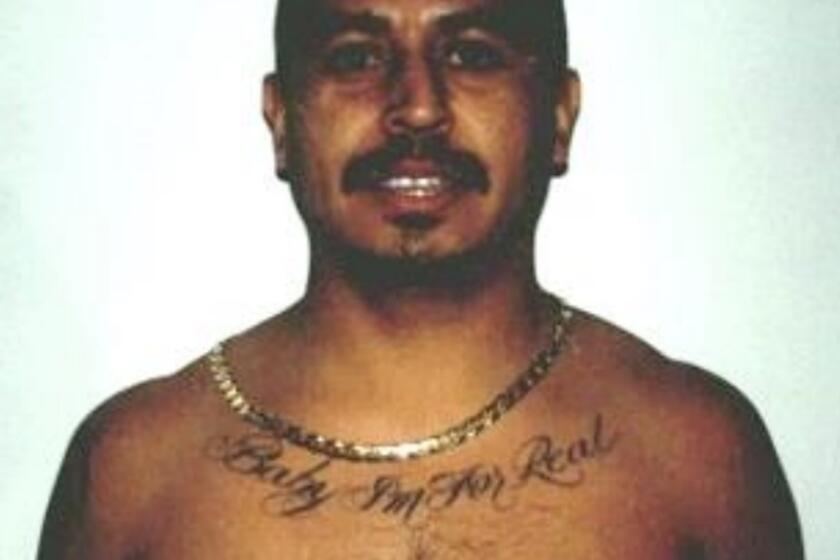

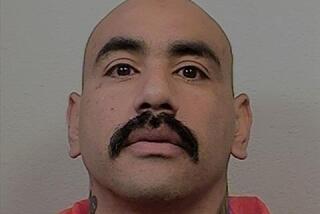

During 14 years on the run, Jose Luis Saenz had cast a shadow over his old Boyle Heights neighborhood. He vanished after his first alleged murder in 1998. An informant warned that Saenz would keep killing until he was caught.

He resurfaced on the Whittier doorstep of a man who’d lost more than half a million dollars in drug money. Police found the man shot to death in his front yard.

After Saenz disappeared again, informants dished rumors: He was in Mexico, freelancing for drug cartels. He was in Guatemala, then El Salvador, slipping across borders to party at nightclubs in Los Angeles or visit one victim’s grave.

Arrested in Mexico, he sat on the Alaska Airlines flight in handcuffs, escorted by FBI agents to a city that had changed profoundly in his absence. By the time he stood trial in 2022, the jury was transported to places that no longer existed. Housing projects just east of the L.A. River where Saenz lived — and allegedly killed — had been torn down. Townhouses, warehouses and a light-rail station took their place.

The gangs that detectives said ruled over the projects, frightening families into returning home before sundown, had dwindled in size and influence, but the legend of Smiley endured.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Witnesses at his trial demonstrated to the jury an abiding principle of gang culture: Don’t tell on anyone, even those who’ve hurt someone you love. Testifying about events some 25 years ago, they couldn’t — or wouldn’t — dredge up memories they’d tried hard to forget.

It was 5 a.m. on a Saturday in 1998 when Juan Pena, a pale, scrawny 14-year-old, followed Saenz into Aliso Village.

The housing project was home to hundreds of families who lived in row after row of two-story concrete bungalows built during the 1940s. The children of Aliso Village went to Utah Street Elementary School, where they met kids from the two neighboring projects, Pico Aliso and Pico Gardens, according to testimony at Saenz’s trial. They grew up together, then joined rival gangs. Classmates turned to enemies.

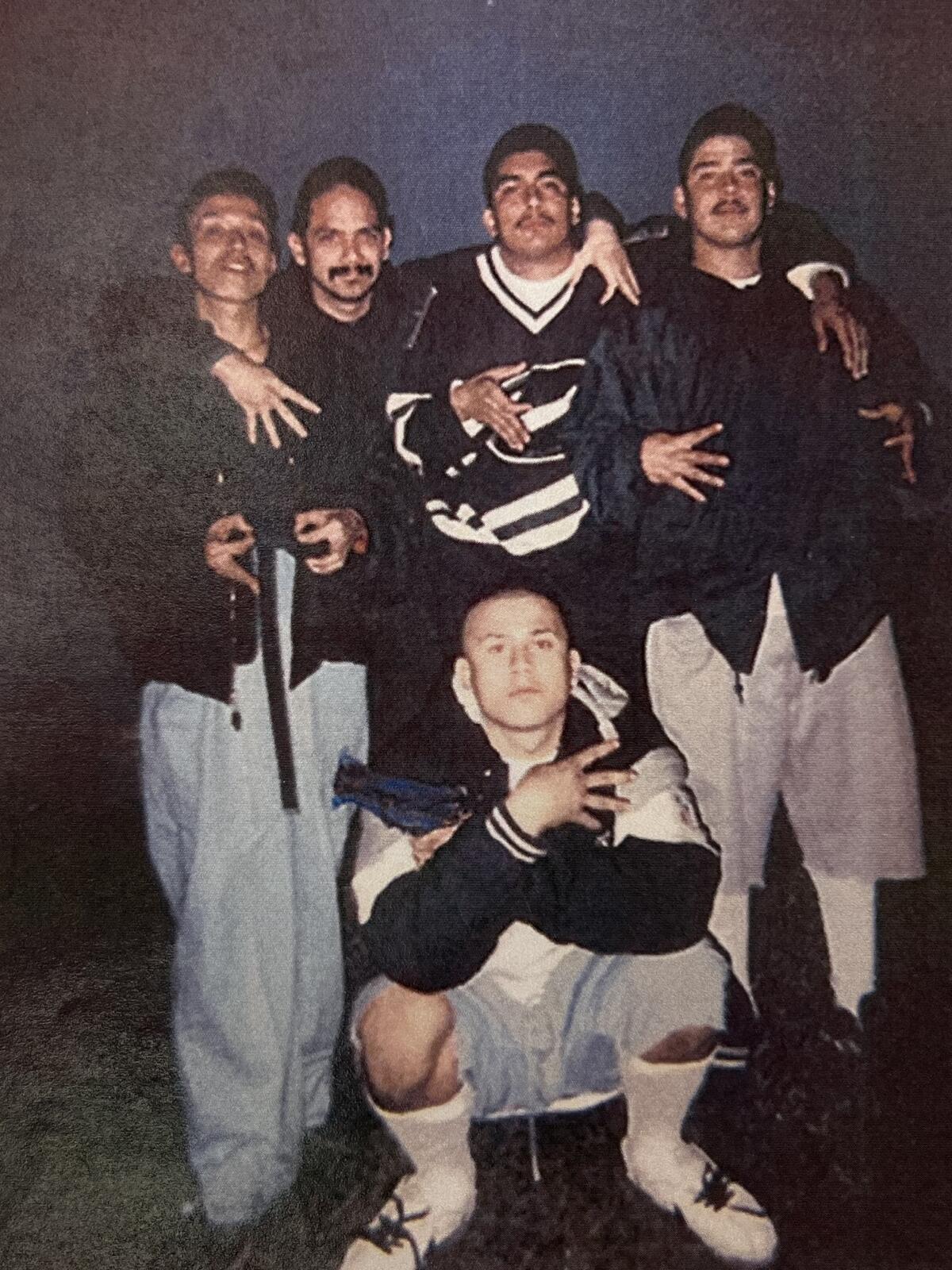

Pico Gardens was claimed by two gangs. The Pico Stoners, who wore their hair long and listened to heavy metal, were “minor league,” a retired policeman told the jury. Saenz and Pena’s gang, Cuatro Flats, was the “big leagues.” Numbering around 100 in the 1990s, the guys from Cuatro Flats wore the gangster’s universal uniform: “Shaved head, white T-shirt and baggy pants,” a detective testified.

According to a tape of his 1998 interview, Pena told detectives he was beaten by one of the gangs in Aliso Village, known as East L.A.-13.

Pena told Saenz of the beat-down. Saenz had his own issues with East L.A-13, Pena told detectives. His girlfriend lived in Aliso Village, and Pena recalled Saenz saying he was tired of the gang “disrespecting” him whenever he visited.

The syndicate once relied on associates on the streets, but court data showed that smuggled phones have given imprisoned leaders greater control over drug deals.

Pena went with Saenz to get a gun, then followed him into the housing project.

In Aliso Village, Martin “Lazy” Partida had been up all night, he testified, selling crack cocaine to homeless people who wandered into the projects. The 17-year-old member of East L.A.-13 was rolling a joint in a stairwell when he heard shots around the corner.

Then came the voice of his homeboy, Leonardo “Shadow” Ponce: “Help me.”

Ponce, 18, was spitting up blood outside an apartment building. He died in Partida’s arms trying to say something. Another member of their gang, Josue “Moreno” Hernandez, 25, lay face down, blood pooling around his head.

Los Angeles Police Det. Marcos Saenz, who isn’t related to Jose Saenz, was called out to Aliso Village. He saw blood spatter on a wall at head height. Graffiti on another wall: “F— All Flakes.” It was East L.A.-13’s insult for Cuatro Flats, whom they called “Corn Flakes.”

How Tupac Shakur’s killing in 1996 brought “10 days of hell” to Compton, with multiple shootings that helped crack the case.

The detective took Partida in for questioning. The teenager’s mother waited outside the interview room as investigators pleaded with him to say who killed his friends.

“There’s not a lot of people that — that actually see the last breaths of somebody who was their friend,” Det. Saenz said. “This isn’t right, man.”

Partida said the shooters were from Cuatro Flats. He didn’t give up any names.

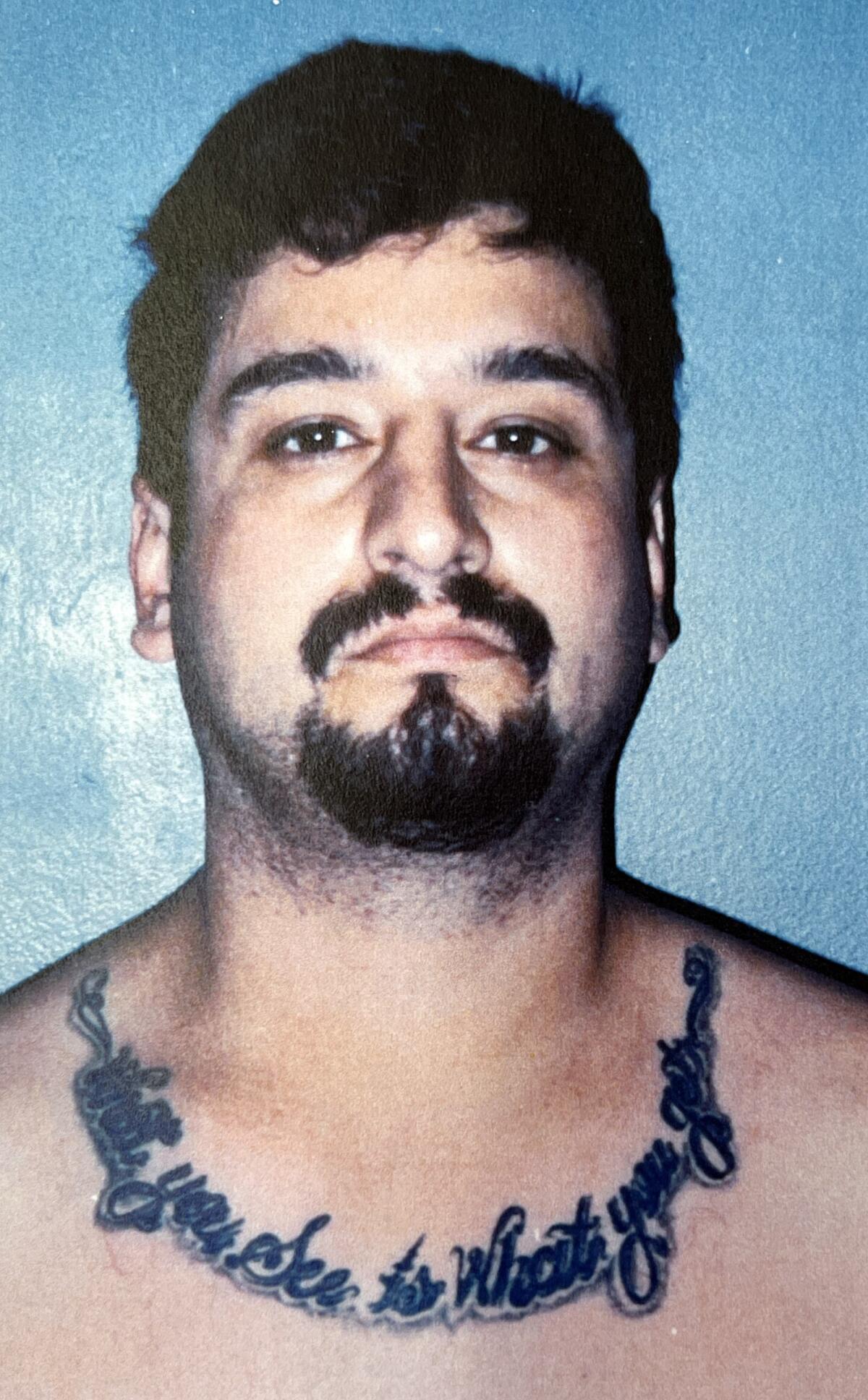

By the time of the double homicide in Aliso Village in 1998, Jose Saenz had risen to the “upper echelon” of Cuatro Flats, a detective testified.

Although only 22, Saenz “already had a reputation of being very violent and putting in a lot of work for the neighborhood,” LAPD Det. Adrian Parga said. “He was very well known not only within his own gang but other gangs.”

A defense attorney was charged in a federal indictment with conspiring to murder a Mexican Mafia member who had fallen out of favor with the prison-based syndicate.

Through a relative, Saenz declined an interview request.

Saenz was raised by his maternal grandmother, according to her statement to detectives. She said his mother was in and out of prison. His father was absent from his life.

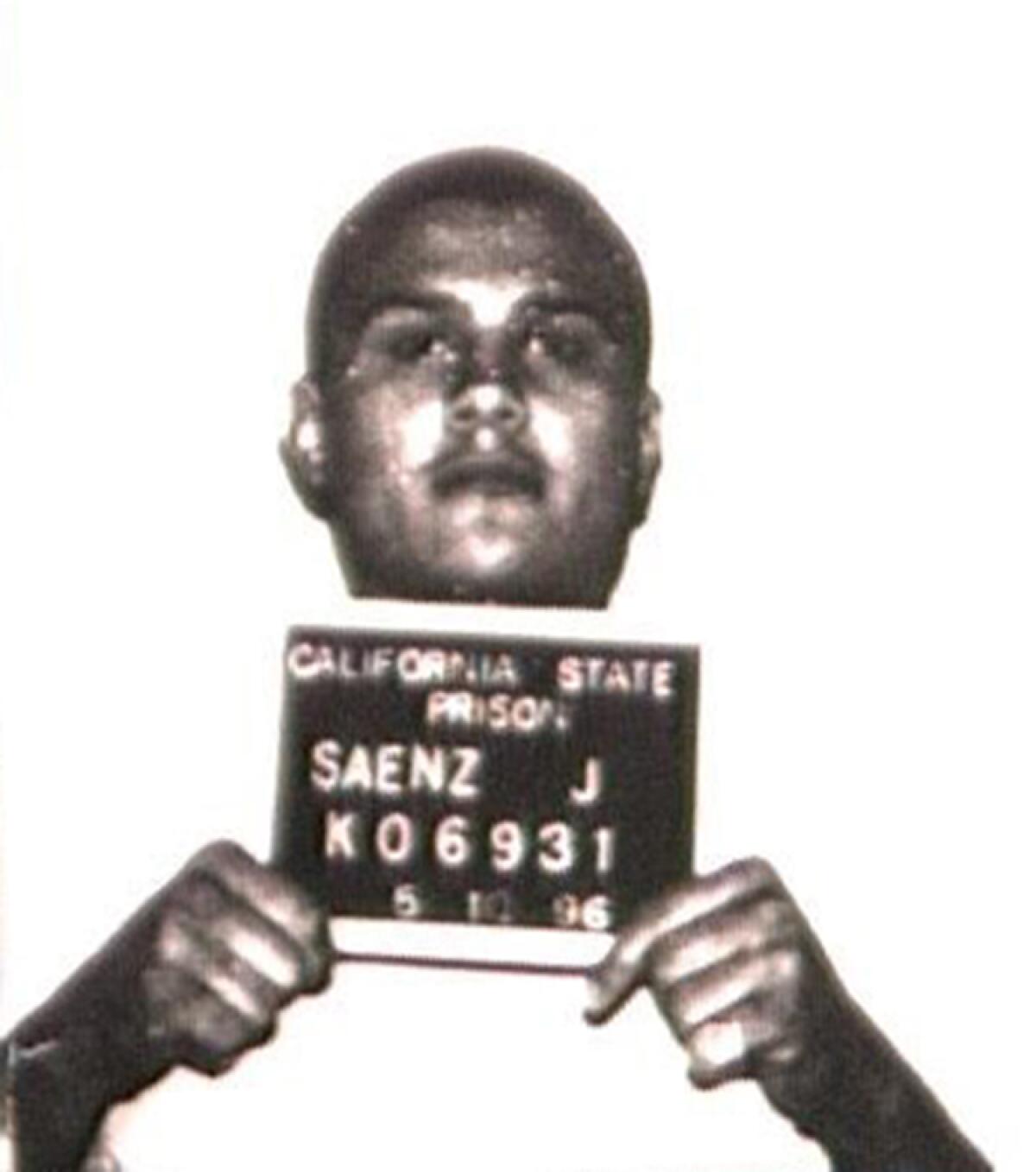

His record started at 14 with an arrest in West Hollywood for petty theft. At 16, Saenz admitted robbing a man and was declared a ward of the court. More arrests piled up for theft and vandalism. At 20, Saenz was convicted of possessing drugs for sale and sent to state prison.

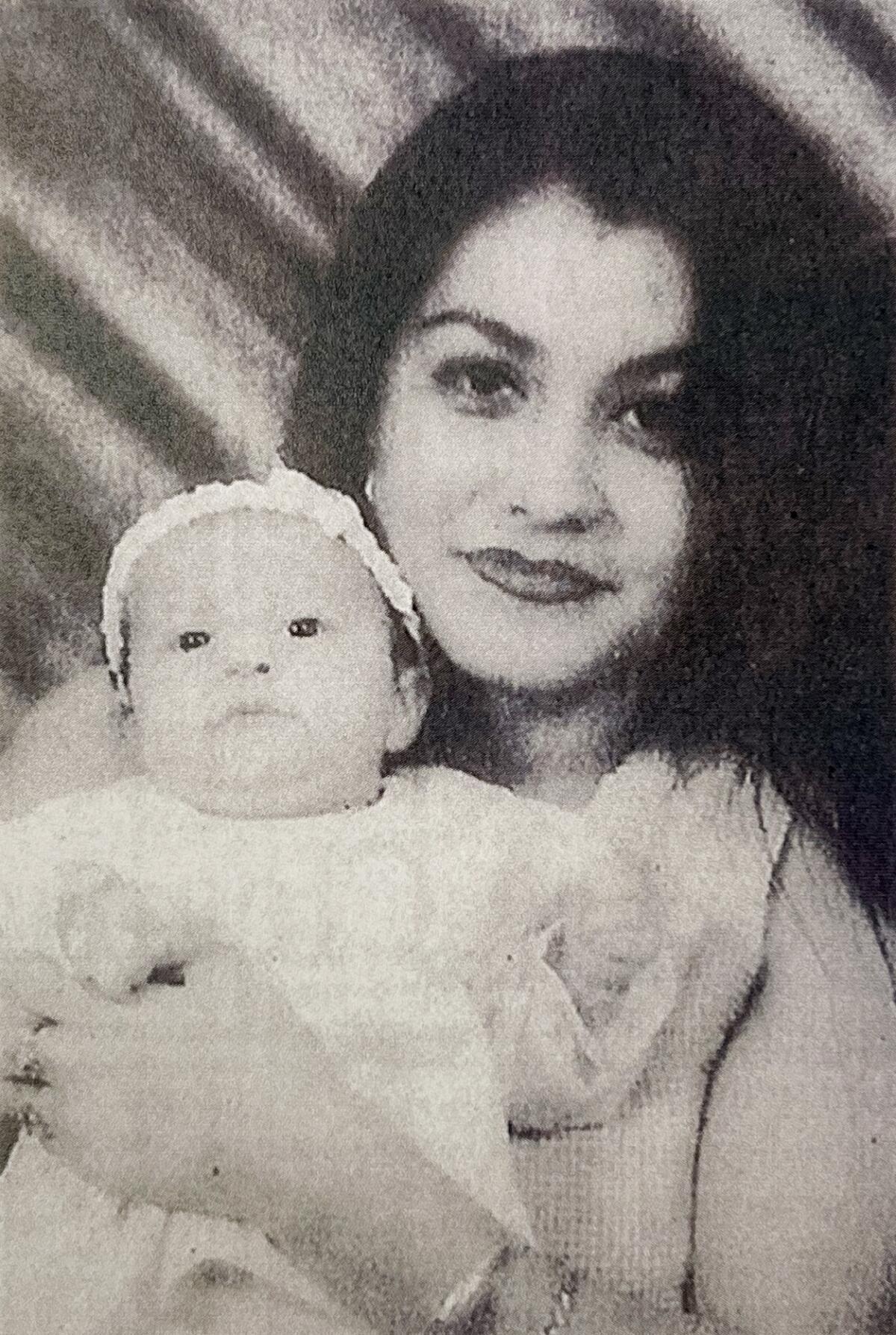

After he got out, Saenz fathered a child with his girlfriend, Sigreda Fernandez, who raised the baby girl at her mother’s home in Aliso Village. The couple fought often — her family once called the police after Saenz poured a beer over her head when she refused to leave a party with him. But they always returned to each other, and Saenz tattooed “Sigreda” on his back.

After the shooting in Aliso Village, Pena told detectives, he and Saenz fled to Fernandez’s home, where Saenz confided in his girlfriend that he’d killed two people.

Eduardo Escobedo, a convicted drug trafficker who worked directly for the son of Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzman, was gunned down Thursday morning in an industrial stretch of Willowbrook.

Eleven days later, Fernandez’s cousin, Pedro Aguilar, was asleep on the couch when he woke to Saenz banging on the door. He opened it and went back to sleep. The sound of an argument woke him again.

Aguilar told different stories about what happened next. On the witness stand in 2022, he testified that Fernandez came down the stairs followed by Saenz, who said: “Nothing is going to happen to her. I need to talk to her.”

But in 1998, Aguilar told detectives Saenz was holding a revolver to Fernandez’s head. He pointed the gun at Aguilar and told him to stay out of it. Fernandez “threw a rat on me,” Saenz said.

It was the last time Aguilar saw his cousin alive.

Five miles east of Aliso Village, Anita Hunnicutt was drinking coffee when she heard a car pull into her driveway on Ferris Street in East Los Angeles. A door slammed. She heard a woman weeping. Then a voice she knew.

“Grandma,” Saenz said. “Open the door.”

She let in Saenz and Fernandez. “Don’t leave me alone,” she recalled Fernandez saying. “He has a gun.”

Saenz said he needed to talk to his girlfriend and told Hunnicutt to go to a friend’s house. He turned off the stove, where she’d been roasting chiles. She left.

“Every time they used to fight,” Hunnicutt said, according to a tape of her 1998 interview, “he used to bring her to my house and they used to make up.”

There was a pleading note in her voice, as if she were asking the detectives to forgive her. “Everything was good. Happy. Everything was all right. And it just so happened that this time ...”

Gabriel ‘Sleepy’ Huerta is an alleged member of the Mexican Mafia’s three-man ‘commission.’ He’s been charged in a more mundane matter: the beating of a Wilmington gang member who lost a gun.

A few hours later, Saenz called her at the home of a neighbor, Carol Vildosola. “Don’t go to the house,” he said, according to Hunnicutt. “Please, Grandma, don’t go.”

She asked Saenz what he’d done. He hung up.

Vildosola went in first. In Saenz’s old bedroom, Fernandez lay in a tangle of sheets on a bare mattress, wearing only an unbuttoned pair of blue shorts. An electric fan was perched on an ironing board, blowing air toward the bed.

Vildosola tickled her feet, thinking she was asleep. “‘Come on, Sigreda, get up. Don’t be lazy, come on,’” she recalled. “And nothing, nothing, nothing.”

She pulled off the pillow that covered Fernandez’s face. She saw the blood and the hole in her head.

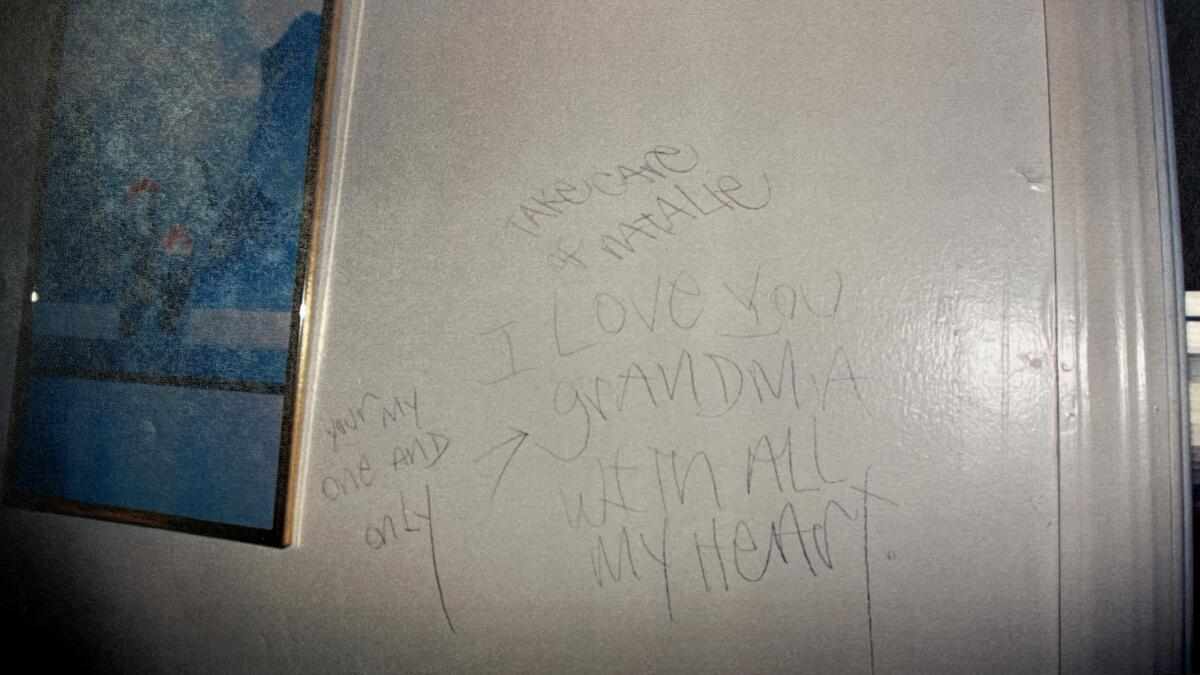

Police found two messages in the house. One, scrawled on an envelope, said: “The guey that drove me did not have nothing to do with anything or my grandma. I kicked her out so f— you putos.”

The other was written on a bedroom wall. “Take care of Natalie,” it said, referring to his and Fernandez’s 17-month-old daughter. “I love you grandma with all my heart. You’re my one and only.”

Wanted for three counts of murder, Saenz vanished.

Pena warned that Saenz would keep killing until he was caught — witnesses, people who owed him money, even a policeman if his freedom were on the line.

“Has he kind of gone psycho?” a detective asked.

“Nah,” Pena said. “He just knows what he’s doing.”

The case offers yet another illustration of how the Mexican Mafia controls and extracts money from inmates held at the nation’s largest jail complex.

Charged with murdering Ponce and Hernandez, Pena pleaded guilty and was sent to the California Youth Authority. He told detectives in 1998 a Jesuit priest had given him hope of finding a new life after prison.

You’re young, the priest had told him. There’s still time to change. Pena didn’t want to die behind bars or in a gang shootout. “I just want to get out where I could still go to school and be something,” the 14-year-old said.

Three years later, he was dead. A rare type of cancer killed Pena while he was still behind bars, said Deputy Dist. Atty. Heather Steggell, who prosecuted Saenz.

Years slipped by. The city razed Pico Gardens, Pico Aliso and Aliso Village. A priest walked the streets with a replica Virgin of Guadalupe to bless their destruction. The concrete bungalows were replaced by modern buildings that looked more like a suburban development than a city housing project.

Scott Garriola, a retired FBI agent who specialized in tracking fugitives, testified he developed a “tree” of Saenz’s friends and family. Agents spied on holiday gatherings and funerals.

The FBI broadcast his story on “America’s Most Wanted” and put his face on a billboard in his old Eastside neighborhood. Call a hotline and land a $100,000 reward: 1-888-CANT-HIDE.

After hearing Saenz had gone to see his grandmother, Garriola installed a camera on a telephone pole facing her house. The camera piped a live feed to an FBI office for three years. Not once did it catch a glimpse of Saenz, Garriola testified.

The agent got another tip: Saenz visited Fernandez’s grave on the anniversary of her death. Garriola staked out the cemetery. Saenz didn’t show.

“At some point the case runs dry,” Garriola testified. “Leads dry up.”

Then, 10 years after he vanished, he got a glimpse of Saenz’s face. It was captured by the surveillance cameras of a dead man.

The sheriff’s deputy was patrolling an interstate in eastern Missouri when he spotted a Chevrolet Impala tailgating other cars. Deputy Nicholas Lineback hit his lights and sirens. The driver’s hands were shaking, Lineback testified, when he handed over a driver’s license that identified him as Sam Palazzola.

The driver said he was returning to Los Angeles from Pittsburgh, where he’d gone to visit family. In the trunk Lineback found dryer sheets, which the deputy said can be used to mask the smell of drugs.

Lineback unscrewed the Impala’s door panels. “All four doors were completely full of money, of vacuum-sealed money,” he testified. It totaled $610,000. The driver and passenger each were carrying $5,000 more in their pockets. The men forfeited the money, and Lineback let them go.

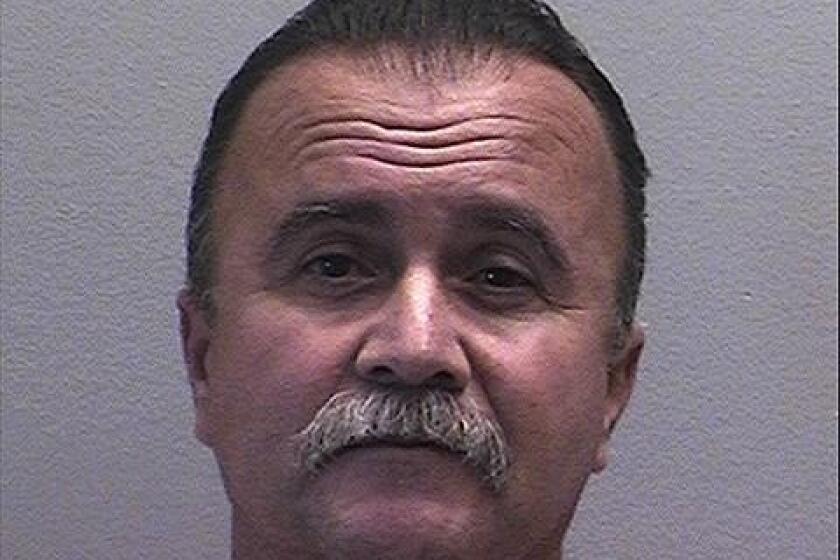

The driver’s real name was Oscar Torres. In East Los Angeles, where he led a gang called the Lott Stoners, he was known as “Easy O.”

Torres owned three homes, traveled often on business and told his mistress his money came from companies that rented out limousines and party jumpers, she testified.

Two years after he lost the $610,000, Torres asked an old friend, Anthony Limon, to chauffeur some friends for a night. Limon drove Torres’ black Hummer limousine to the Elephant Bar in Downey, where he picked up a man who introduced himself as “Toro,” Spanish for bull.

It was Saenz.

Limon took Saenz and his friends to El Parral, a nightclub in South Gate. As the night wound down, Saenz asked Limon to drive him and another man to Torres’ home. Limon needed to use the restroom, so he parked the limousine and accompanied his passengers to the front porch.

Torres opened the doors in his boxers. Saenz and the other man pulled out guns, Limon testified: “I said, ‘What the f—?’”

Something hit the back of Limon’s head. He lay on the ground, blood pooling around him, he testified, when he heard someone say, “Dome him.” He was shot in the chest and left for dead.

Torres’ cameras captured the scene in grainy black and white: Torres runs out the front door in his underwear. A man chases after him. Muzzle flash. A third man wipes the doorknob with a piece of clothing. Two men drive off in the limousine, leaving Torres’ body on the front lawn.

The man was carrying a Salvadoran identification card in the name of Walter Alexander Alfaro Garcia when Mexican Federal Police arrested him in 2012. His hair had grown out. He was flabby at the waist. He’d removed many of his tattoos, but not a familiar name on his back, the name of the mother of his child: Sigreda.

Garriola testified that the FBI and Mexican authorities finally located Saenz in Guadalajara after years of tracking phones used by his associates.

A decade after his arrest, a Los Angeles Superior Court jury came back in 2022 with a verdict. It convicted Saenz of raping, sodomizing and murdering Fernandez. They found him guilty of murdering Torres and attempting to murder Limon. They could not reach a verdict on whether Saenz gunned down Ponce and Hernandez in Aliso Village.

Los Angeles County prosecutors allege that Juan ‘Termite’ Romero set fire to a crowded apartment building, killing seven children and three women.

At 17, Partida told detectives he didn’t know who killed his friends. Testifying 24 years later, he stuck to his story. Sitting across the courtroom from Saenz, Partida told the jury: “I never seen him before.”

Before sentencing Saenz to life in prison without parole, Judge Larry P. Fidler asked if he had anything to say. Saenz protested that he’d been denied a fair trial. “I’m innocent, for the record,” he said.

“For the record, you’re not innocent,” Fidler said. In his 40 years as a judge, 10 years as a defense attorney and three years as a court employee, “you are as cold-blooded a killer as I’ve ever had come before me in my entire life,” he told Saenz.

“I’m not a biblical person,” Fidler said, “but I do believe in good and evil.”

The judgment didn’t change the wreckage that Saenz left behind. Fernandez’s cousin, who had to be hauled into court to testify, said his family never forgave him for opening the door to Saenz.

“I just want to leave it alone like it is and forget about it, you know?” Aguilar said.

What about justice, the prosecutor asked. What about closure?

“Well, how am I going to see that?” Aguilar said.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.