This is the first in a four-part series on how Latino political power has changed Los Angeles.

PART I: THE EASTSIDE’S PERPETUAL DESMADRE

Sipping on an iced cappuccino, Antonio Villaraigosa beamed as he described the pinnacle of his career.

His late-1990s stint as speaker of the California Assembly? Nah. Serving as the first Latino mayor of Los Angeles in 133 years? Important, but that wasn’t it. Continuing to advise political hopefuls across Los Angeles County? Nope.

No, what prompted Villaraigosa to happily reminisce for a good hour was his success as a peacemaker in the eternal civil war that’s politics on the Eastside.

Rivalries are part of any region’s politics, but in the cradle of Latino power in Los Angeles, they are biblical. Here, friends turn into enemies, and enemies become friends, as a parade of politicians jump over, around and on one another like a game of “Frogger.”

The road to influence has been full of trials and triumphs. From the Eastside to the Valley to South L.A. to Southeast L.A. County, columnist Gustavo Arellano dives into the key moments and alliances.

Villaraigosa was in the middle of what was long the Eastside’s defining feud: pioneering politicos Richard Alatorre and Art Torres versus their former associate Gloria Molina. Through the 1980s and 1990s, they and their followers brawled from Sacramento to City Hall to the county Board of Supervisors, in skirmishes that The Times once politely described as “downright mean.” The two sides even went by nicknames — the Torristas and Molinistas — and claimed restaurants facing each other on Olvera Street (El Paseo Inn and La Golondrina Cafe, respectively) as hangouts.

When Villaraigosa won his Assembly seat in 1994, he represented something different. A rabble-rousing activist with roots in L.A.’s labor movement, he had entered Eastside politics as Molina’s representative on what later became the Metropolitan Transportation Authority board. He frequently found himself on the losing side of votes orchestrated by Alatorre, then a council member and the board’s chair.

In Los Angeles, “Latinos were quickly becoming the dominant ethnic group,” Villaraigosa said. “All that infighting undermined the power that could come with being that dominant.”

The main issue that drove the secret discussion — where does Latino political power stand in L.A.? — remains as vital and vexing to the future of Los Angeles as ever.

After years of jostling with Alatorre and his protege, Richard Polanco, Villaraigosa won over the former and checkmated the latter in his successful run for mayor in 2005.

A Pax Chicano took hold on the Eastside for 15 years — something not seen in decades. Villaraigosa’s favored candidates rose, with only token opposition.

“I knew there was no way to get to the mountaintop with us warring between one another,” he said, stopping from time to time to take phone calls for his consulting business as we sat outside a coffee shop near downtown. “What are we going to do? Like the Hatfields and McCoys?”

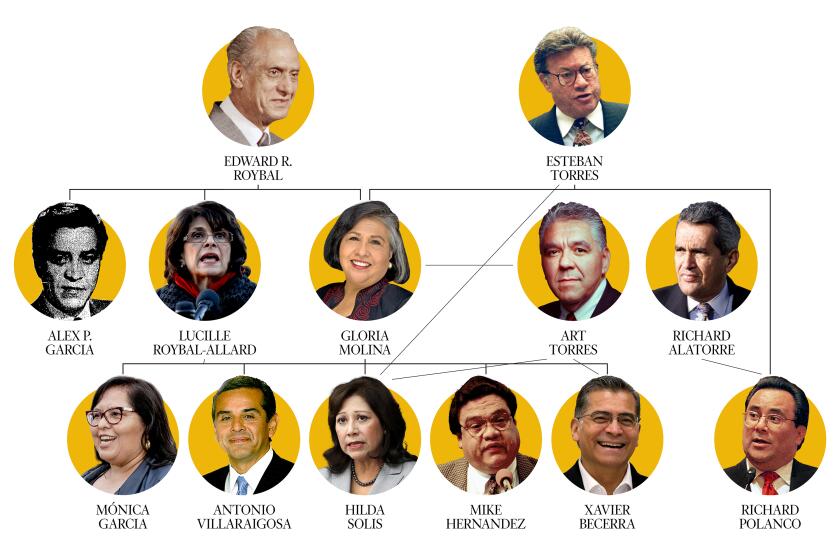

Connections among Latino politicians in Los Angeles can get confusing. We attempt to decipher the oldest political trees: the Eastside and the San Fernando Valley.

Yet that’s what’s happening again on the Eastside.

The battlefield is the forever battlefield: the 14th City Council District. It’s a land of contrasts — downtown and Skid Row, heavily Latino Boyle Heights and El Sereno, gentrified Highland Park and suburbanesque Eagle Rock — represented by a Latino since the mid-1980s. Among those who have occupied the seat are the most iconic and, in some cases, the most infamous of L.A. politicians: Alatorre, Villaraigosa, Jose Huizar, who was sentenced in January to 13 years in federal prison for racketeering and tax evasion.

And, of course, the sitting council member, Kevin de León, who has remained in power despite calls by Villaraigosa and others to resign after he was captured on a recording with other politicians in a conversation that belittled Black people, Oaxacans and Jews, among others .

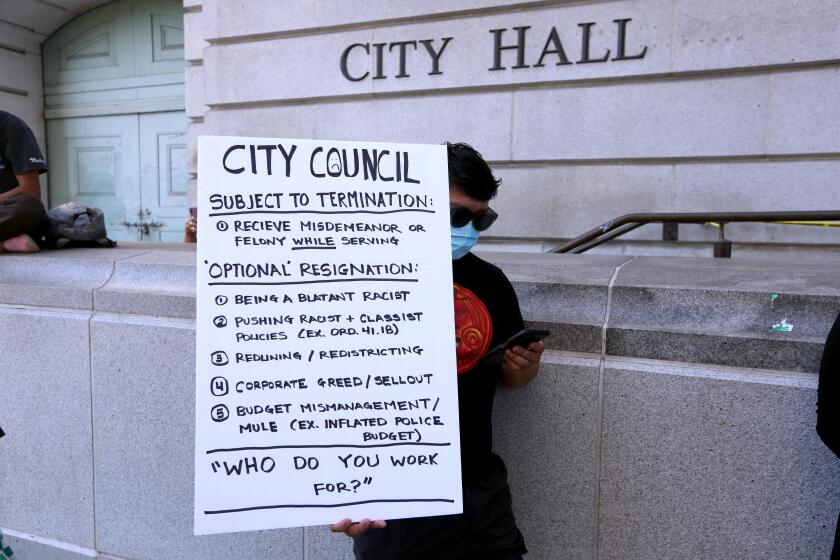

Rough-and-tumble politics are nothing new to L.A.’s 14th District

Seven people are challenging De León for his seat, including two former fellow travelers, Assemblymembers Wendy Carrillo and Miguel Santiago. The splintering echoes a comment De León made on the tape, bemoaning the lack of Latino political unity in Los Angeles compared with Black power.

“They shout like they’re 250,” he said, “when there’s 100 of us, and it sounds like it’s 10 of us.”

The 14th’s state of being has longtime observers asking a question that sounds like a joke but isn’t: Why do politics on the Eastside always devolve into desmadre — chaos?

The Eastside is the axle from which the rest of L.A.’s Latino power wheel springs. The struggles for representation and equity at City Hall and the state capitol, waged decades ago by Eastside politicians, inspired Latinos nationwide. In L.A. today, power is no longer relegated to where Latinos live — it’s citywide.

When the axle squeaks, as is happening in the 14th yet again, the rest of Los Angeles should watch out.

“Is it a special brew in the 14th that they all catch? I don’t know,” said Jaime Regalado, a professor emeritus of political science at Cal State Los Angeles. “It’s the opposite of being blessed, for sure.”

Eastside politics weren’t always so messy.

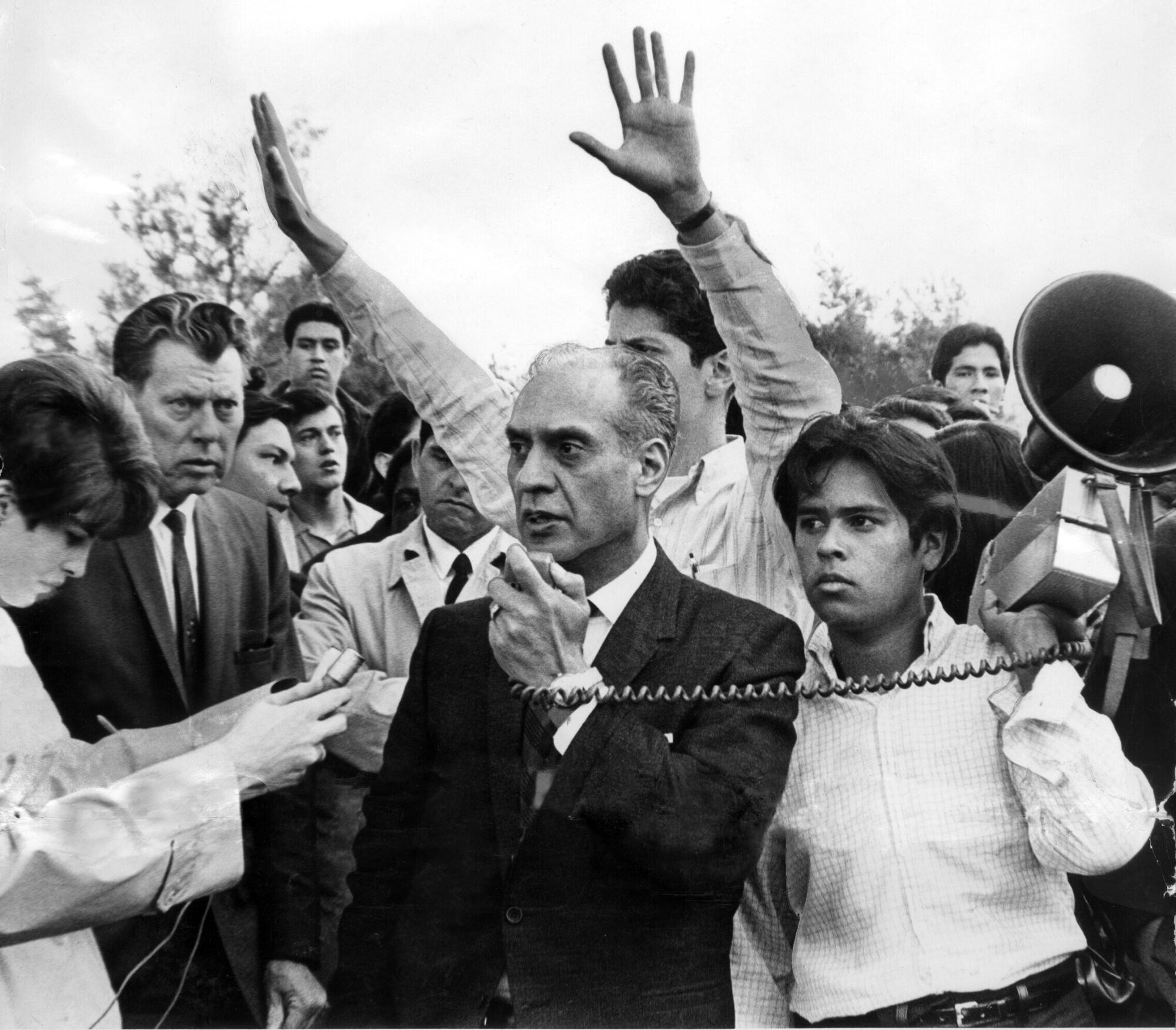

In 1949, a coalition of Latino, Jewish and Black voters elected Edward Roybal, L.A.’s first Latino council member since the 1880s, to represent a district that sprawled from the Eastside to Little Tokyo to South Los Angeles. After ascending to Congress in 1962, Roybal supported the appointment of Gilbert W. Lindsay to replace him and become the city’s first Black council member.

As Black L.A. began to build political power, Mexican American leaders itched to get one of their own back into City Hall. Young Chicano activists walked out of high schools and staged marches demanding political representation and an end to civic neglect of the Eastside. Heeding their calls, the City Council redrew district boundaries in 1972, lopping off Boyle Heights and El Sereno from Lindsay’s district and putting them in the 14th.

Latino activists in Los Angeles often refer to a “political machine” that operates on the city’s Eastside.

Only one council member voted against the plan: 14th District incumbent Art Snyder, a glad-handing, Spanish-speaking Irish American who had occupied the seat since 1967.

He called the realignment a “political assassination” of his whiter, wealthier Northeast constituents. But those voters ensured the district “was going to have a non-Latino incumbent for a long time,” said Regalado, an El Sereno native. Warring factions created razor-thin margins that kept Snyder in office despite many attempts to oust him: He survived a 1973 recall attempt, averted a runoff in the 1983 primary by just four votes and beat another recall in 1984.

Snyder finally resigned in 1985, citing personal “pressures,” after racking up a drunk driving charge in a city car, among other issues. He was replaced by Alatorre, who had spent the previous decade eclipsing Roybal’s influence in the Eastside with his friend, Torres.

The two had served in the Assembly through the 1970s, amassing power in Sacramento that allowed them to influence California’s congressional and legislative redistricting. In a bitter 1982 race for state Senate, Torres beat longtime incumbent and former Roybal field deputy Alex P. Garcia. Torres then suggested to Molina, his former administrative assistant and a onetime Alatorre campaign volunteer, that she run for the Assembly seat he was vacating.

There was one problem: Alatorre and others in his machine had already blessed Polanco to replace Torres.

“They were accustomed to the role they played: Big chingones [badasses], they’re in charge,” Molina told The Times in 1993. “They didn’t want some pipsqueak like me coming in.”

After announcing she has terminal cancer, Gloria Molina reflects on her career as a trailblazing Latina politician.

Molina forged ahead, beating Polanco in the 1983 Democratic primary on her way to victory. Four years later, she joined Alatorre on the City Council after defeating his favored candidate, then finished her trifecta by triumphing over Torres in 1991 for a seat on the Board of Supervisors.

The beef between the former allies — all Democrats — trickled down to fashion and policy. Torristas favored expensive suits, blunt words, fancy dinners and backroom deals. Molinistas fancied themselves pragmatic do-gooders who weren’t above shopping at Ross Dress for Less and believed in people power above caciques — larger-than-life leaders.

The vicious circle of fights mostly ceased after Villaraigosa brokered the uneasy peace. He combined the fire of his old boss Molina and the bon vivant verve of Alatorre’s crew to work the picket lines as easily as he did banquets. He helped bring the rivals together when the Eastside truly needed it: Proposition 187, the future of L.A. County-USC Hospital in Boyle Heights, the expansion of the Metro Gold Line that cuts through the 14th.

“What was funny about it,” Villaraigosa said, “was it was a love-hate relationship. Because a lot of [the Torristas and Molinistas] had grown up together.”

Alatorre left office in 1999 and pleaded guilty in 2001 to federal tax evasion before emerging from political exile when Villaraigosa won in 2005. Torres served as chair of the California Democratic Party from 1996 to 2009, when the state electorate was transforming from purple to deep blue. Molina, who died of cancer last year at 74, remained on the Board of Supervisors until she was termed out in 2014.

By the time she left office, a new political faction had taken over the Eastside: labor.

Unions had traditionally sided with Alatorre and Torres over Molina. But Villaraigosa’s rise in Sacramento and Los Angeles created the path for former union organizers to run for office themselves, including his high school pal Gil Cedillo, cousin John A. Perez and friends Maria Elena Durazo and Fabian Nuñez. Labor and immigrant rights became a priority at City Hall and the state Capitol, with Nuñez and Perez serving as Assembly speaker while Villaraigosa was mayor.

The Molinista-Torrista rivalry was relegated to the archives; the last of that generation are Supervisor Hilda Solis and U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra. New faces broke through the Eastside’s political thickets: Rocky Delgadillo became city attorney in 2001, while Huizar replaced Villaraigosa as the 14th District’s council member in 2005.

A generation of Eastside Latino political staffers came of age, long removed from the strife of before, and waited for their turn to seek elected office. Huizar’s downfall strained those alliances. The racist City Hall tape featuring Cedillo and De León made them crumble.

Here is a look at former Los Angeles City Councilman Jose Huizar and the City Hall corruption case against him.

“It’s like that thing where you reach the end of the world, and you’re in a situation where there’s no place to go — crazy things happen,” said Tony Castro, a journalist who has covered Eastside politics on and off for 45 years and got caught up in his own 14th District problems. In 1983, a Times story revealed that he had authored campaign memos for a City Council candidate while writing puff pieces about the candidate for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. “[The Eastside] is for the people who want it more. If you have it in you, it’s a place to shine.”

Far less charitable about the 14th’s perpetual scuffles was Alvin Parra, a former Roybal and Molina staffer who came close to unseating Alatorre in 1995 and ran unsuccessfully two more times, including in 2007 against his former boss Huizar.

“It’s just like musical chairs,” said the El Sereno resident, who is now a financial consultant. “It’s a game of scarcity, and the losers are the constituents. The chairs are running out, and where else can they go?”

Carrillo decided to run against De León after Latino leaders across the city called for his resignation because of the leaked tape.

Carillo, a former radio host and communications manager for SEIU Local 271, has lived in the Eastside since moving to the U.S. from El Salvador as a child. Last fall, she characterized De León and Santiago as “two men fighting each other for power” who didn’t grow up in the district — Santiago is from Canoga Park, and De León was raised in San Diego.

A few days after our conversation, Carrillo was arrested on suspicion of driving under the influence after she crashed into two parked cars near Highland Park. Her blood-alcohol level was at least twice the legal limit, according to the LAPD. Last month, she pleaded no contest to the DUI and remains in the race.

In a phone interview, Santiago stayed silent for a while when I asked if he was sad about facing off against De León — a mentor who was once one of California’s most powerful Latino politicians, as leader of the state Senate — and Carrillo, his fellow Eastside Assembly member.

“What’s sad is what happened here,” Santiago finally responded, referring to the notoriety surrounding the tape. In it, Cedillo and De León not only gripe about the lack of Latino political power in Los Angeles but also openly express fear that a new generation of Latinos, who don’t subscribe to the identity politics of the past, is ready to take them on.

De León’s office declined multiple times to make him available for an interview.

When I asked if the latest fracturing was bad for the Eastside, Villaraigosa said, “I just don’t buy that this is what that is. We’d all be supporting Kevin. But Kevin f—ed up. And you know, when you f— up, you’ve got to pay.”

De León arguably opened up the Eastside’s latest fissures last year by running for mayor despite having vowed to serve a full term when he replaced Huizar in a 2020 special election. The leaked tape made him even more of a political pariah, but he stood stubbornly firm through a year of protests — including some at his Eagle Rock home — that included a failed recall attempt and angry speakers calling for his resignation during City Council meetings. In an essay last fall, Castro compared De León’s capacity to survive and reinvent himself to the lead character in “The Great Gatsby.”

In Ramona Gardens, a community of 488 households where there were 453 drug-related arrests last year, a place where small children ask strangers if they are policemen, there are no yard signs, no pictures of smiling candidates or no other indications of Tuesday’s Los Angeles City Council election.

Villaraigosa, who is supporting Carrillo, isn’t concerned that former allies are facing off yet again in the 14th District, or that the Eastside continues to see what he described as pleitos — squabbles.

“You know what?” he said, sitting up straight to emphasize the point. Jovial and fit as ever, he had sheared the curly, gray locks that he grew out during the pandemic and looked at least a decade younger than his 71 years. “In some ways, they were such hard-fought battles that the people that won ended up being strong.”

That’s not how Henry Perez feels. Perez, whose family migrated to Boyle Heights from Mexico in the early 1900s, is the executive director of InnerCity Struggle, an Eastside nonprofit that has called on De León to resign.

“Unfortunately, our community has placed their trust on these individuals and has been let down,” said Perez, who attended graduate school at UCLA with me. “You have elected officials that are more focused on fundraising and campaigning for their next seats than serving their districts and communities.”

In October, InnerCity Struggle led a community forum at its headquarters off Whittier Boulevard titled “We Are CD 14.” Sandwich boards displayed the results of a survey asking more than 200 Boyle Heights households what they wanted to see in their next council member.

The top two attributes were “honest communication” and “transparency.” At the very bottom was “influence.”

More than 60 people sat underneath a tent in InnerCity Struggle’s parking lot. Perez stressed that the nonprofit wasn’t endorsing any candidate but that everyone should make a wise choice — especially given the 14th District’s history.

“Has it been what we wanted? Has it been what we needed?” he asked, as many in the crowd shook their heads in dismay. “The prototypical elected official of CD 14 — they put individual power and ambition in front of the community.”

Perez stopped.

“We have one of those in office right now.”

He had let the candidates know they were welcome to attend but wouldn’t be allowed to address the audience. Two showed up: Santiago and Ysabel Jurado, a housing rights attorney who is favored among L.A. progressives and has the endorsement of City Controller Kenneth Mejia and 1st District Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez, who upset Cedillo last year. If elected, Jurado would be the first Filipina American and first LGBTQ+ person to represent the Eastside.

Wearing jeans and a black T-shirt that read “¡Cuando luchamos, ganamos!” (When We Fight, We Win!), Jurado applauded and chanted with participants, who discussed issues that all those political clashes had barely begun to solve: good jobs, safe streets, affordable housing. She stayed until the very end to blend into the crowd for a group photo, a fist up like everyone else.

Santiago was long gone by then, because he had a date with his wife. The Assembly member, who has far out-raised his opponents with the help of union donations, had briefly chatted with Perez on the sidelines as he waited for people to greet him. When few did, Santiago stepped into the tent and largely stared as residents talked among themselves or with Jurado.

Near InnerCity Struggle’s entrance, Jasine Cumplido listened as a volunteer talked about the lack of affordable housing in the district.

“Whoever is the council member, they just need to be actually engaged with residents and actually want to stay here,” said Cumplido, a Boyle Heights resident. She continued the conversation with housing rights advocate Eva Garcia, also of Boyle Heights.

“We’re tired of poliquillos [damn politicians] who treat us like a staircase,” Garcia said in Spanish. “They’re looking at us for their own personal growth. Well, we’re not benches for no one.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.