Column: These California memoirs will get you thinking about writing your own

Writing a memoir is an act of both selfishness and selflessness.

On one hand, who are you to think that your life is important enough for others to want to read about it? You were born, you grew up, you’ll die — tell the world something new.

On the other hand, your story is important — especially if you’re a Californian.

As we approach the 175th anniversary of our statehood in 2025, now is the time to capture on paper, video or audio what you’ve experienced. We’ve been at the forefront — both good and bad — of trends that influenced the course of American history, if not the world, and it’s vital we document what we’ve seen while we can.

That’s the theme that came to my mind as a slew of memoirs by Californians, famous and not, crossed my desk this year. The insights, triumphs and tragedies in my four favorites offer a way forward to tackle the Golden State’s uncertain future — and serve as a challenge for you to put down your own thoughts for future generations.

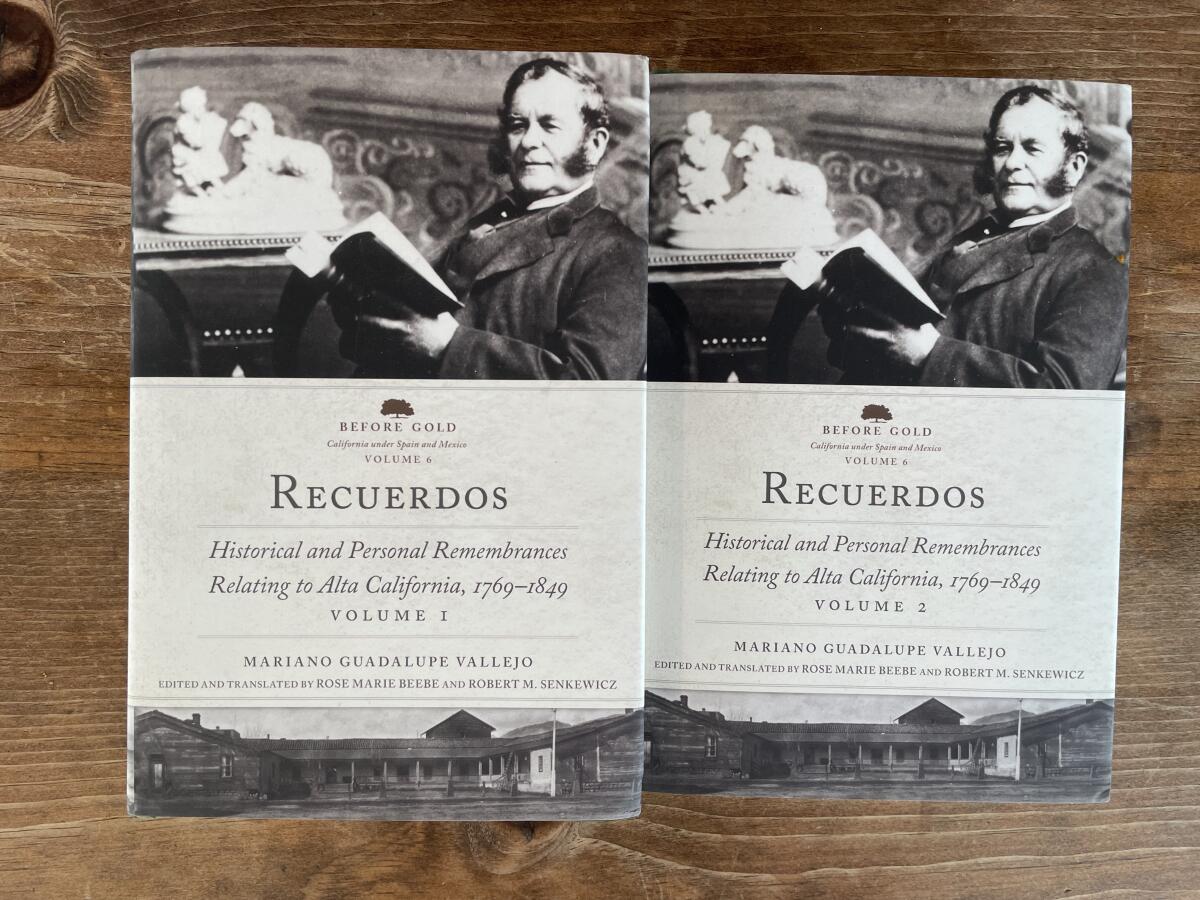

Latinos have always struggled to have their memories included in the California experience. Take “Recuerdos: Historical and Personal Remembrances Relating to Alta California, 1769-1849” by Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, which was written in Spanish in 1875 and finally published in English this year by the University of Oklahoma Press. The author, for whom the city of Vallejo is named , is a titan of California history, someone who fought the U.S. invasion of the late 1840s, then participated in the state’s Constitutional Convention.

It’s not a quick read at two volumes, 1,345 pages and over 100 maps, photos and illustrations — but it’s a necessary one.

In a florid style, Vallejo retells everything from the Portolá expedition — the first time Europeans explored California by land — to the Gold Rush through historical digging, government records and his own memories and opinions. He directs many harsh words toward the Yankees who “so scandalously stripped” Californios of their holdings and held Mexicans in low regard almost from the moment the two groups encountered each other. Writing about how San Francisco schools taught German but not Spanish in his later years, Vallejo writes, “The Germans are praised to the sky, while the Hispano-Americans are despised.”

Vallejo had every reason to be upset, and not just because of the loss of power and land. Rose Marie Beebe and Robert M. Senkewicz, the editors and translators of “Recuerdos,” reveal in a great introduction how Vallejo’s magnum opus was one of dozens of Californio testimonios (oral histories) gathered by Hubert Howe Bancroft, the dean of California history. Instead of publishing them in English, Bancroft reduced them to sources for his seven-volume “History of California.” His series served as the definitive work on the subject for decades, while Vallejo’s effort and the memories of his fellow Californios gathered dust in archives for over a century.

“Well, if Bancroft does not believe what I and others say, Bancroft can just go to hell and write his history there,” Vallejo wrote on the margins of his copy of Bancroft’s work. “Bancroft has no business doubting those who know more about the events than he does.”

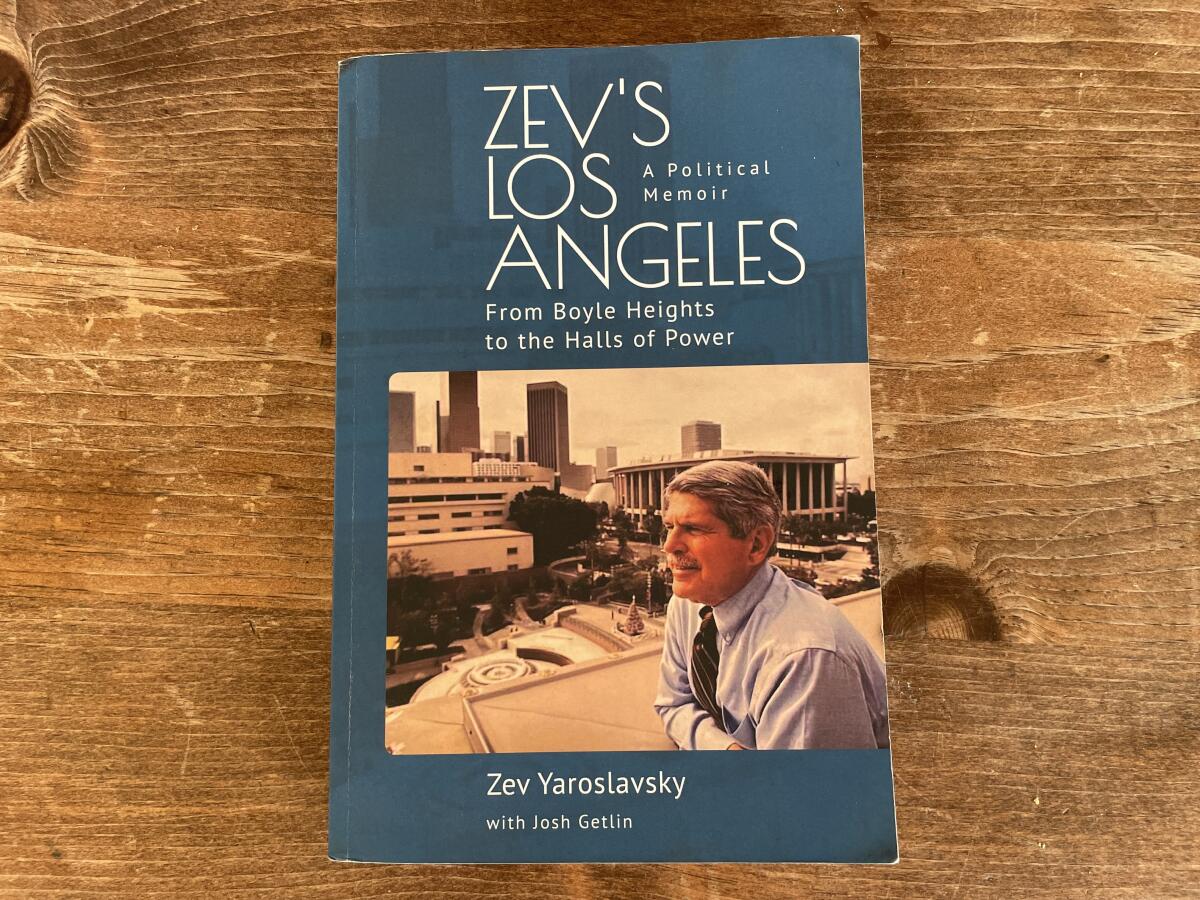

I’m sure longtime L.A. County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky would’ve loved to have over 1,000 pages to unspool his own remarkable story. But “Zev’s Los Angeles: From Boyle Heights to the Halls of Power” is no less of a sprawling, rollicking California tale. The son of Ukrainian immigrants turned one of the most important politicians in post-World War II Los Angeles walks readers through his life and career with anecdotes and asides in a style that’s just like him — plain-spoken, insightful, confident and crusading.

He tells the backstories behind his greatest hits — the fight over Proposition 13 and against Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates, the near-bankruptcy of L.A. County in the early 1990s, his time on the L.A. City Council and county Board of Supervisors. Though out of office since 2014, Yaroslavsky makes sure to offer his thoughts on Mayor Karen Bass (good), Southern California’s homelessness crisis (bad) and county governance (he favors an elected official who can run the county instead of a five-supervisor system that “puts no one in charge”). But the most Yaroslavsky episode is one that few talk about today: the decadelong fight over the removal of a cross from the county seal.

He introduces the tale by recalling how every Christmas, the side of L.A. City Hall would light up with a cross visible all the way to his family’s apartment in Boyle Heights. Why didn’t L.A.’s leaders, Yaroslavsky would ask his dad, also put up a Star of David? Fast-forward to 2004, when he and fellow supervisors Yvonne Burke and Gloria Molina voted to remove a cross from the L.A. County seal, arguing it would save taxpayers from an ACLU lawsuit.

Hundreds of people protested, and conservative commentators vilified Yaroslavsky. Not only did he not back down, he directly engaged with opponents. He recounts taking over the phones from his secretaries to answer dozens of angry calls, including from an Armenian Christian woman who had taken his mother’s Hebrew class at Los Angeles City College in the 1950s. They agreed to disagree but “on extremely friendly and respectful terms.”

It’s classic Yaroslavsky — an approach this country needs during these politically volatile times. “We must find and elect … leaders with character and integrity,” he writes in an epilogue. “They are the ones who will shepherd our democracy into the future. If we fail, we do so at our own peril.”

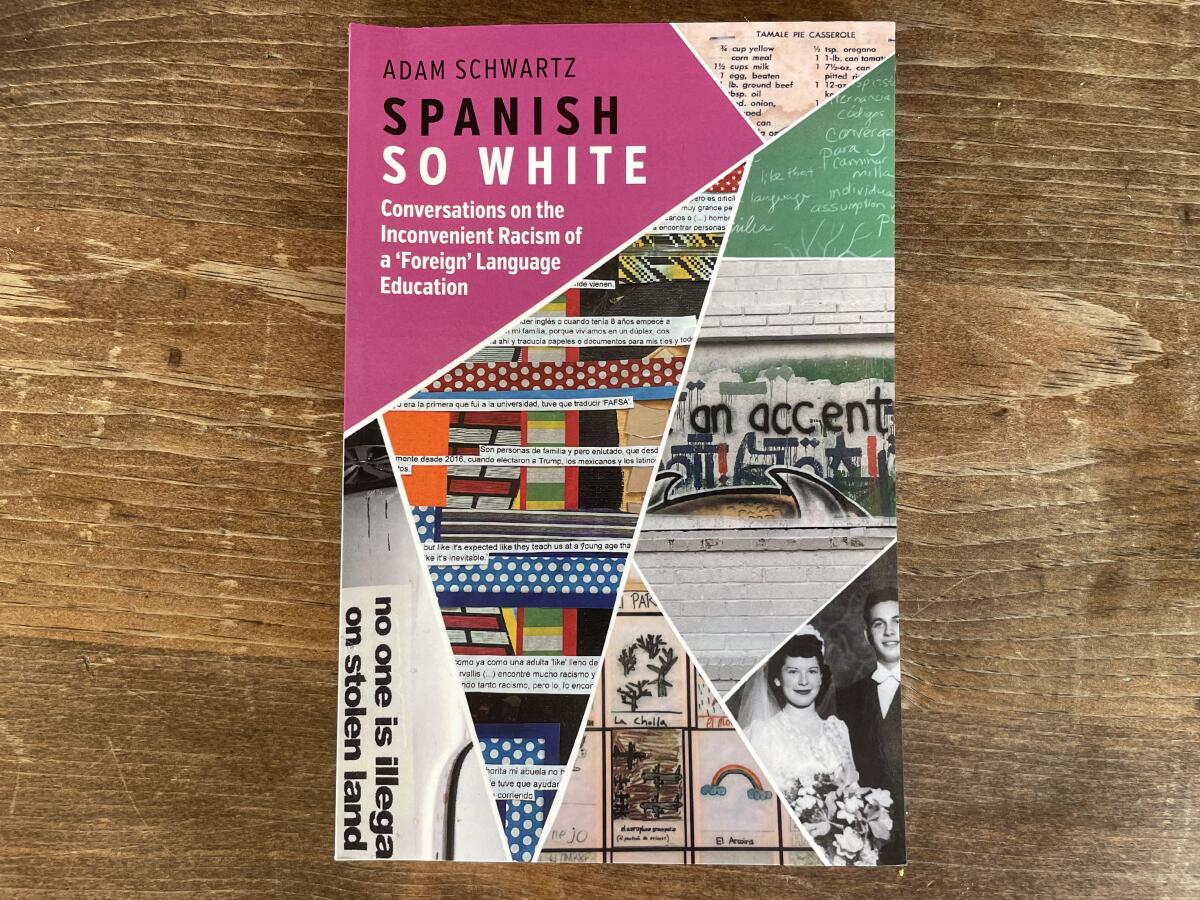

Speaking of mensches, Oregon State professor Adam Schwartz is a nice Jewish boy from the Tarzana side of the San Fernando Valley who published his own L.A. memoir, “Spanish So White: Conversations on the Inconvenient Racism of a ‘Foreign’ Language Education.” It’s technically a textbook designed for gringo teachers and Spanish learners that challenges their ideas of whiteness and Spanish in this country.

I know: It sounds like an academic bore, and it looks like it, too. Schwartz offers group and individual exercises, cites wokoso favorites such as bell hooks and Mike Davis and begins chapters with quotes and key phrases that can easily make a layperson roll their eyes. While I’m familiar with “praxis,” I had to figure out what “indexicality” means. But Schwartz — who invited me to speak to his class years ago — embeds all of this within one of the most unique, soulful L.A. memoirs I’ve read in years.

His battleground is an educational system that favors white and Jewish students like himself and belittles the insights of Latinos. Schwartz tracks his scholastic life with hilarious and touching photos and tales from elementary school to junior high — where he chose to go by “Francisco” in his Spanish class, a name he even put on his Jamba Juice employee badge — through helping students cope with COVID and Trump. The profe, an applied linguist whose specialty is Spanish language education in the U.S., argues that his journey to becoming an acolyte and advocate for the language of Cervantes is one anyone can take — and one that betters us all.

“Dialogue involves careful listening, even when one is tempted to speak or turn away,” he writes early in the book. “Dialogue therefore is likely to invite discomfort, and that’s to be expected.”

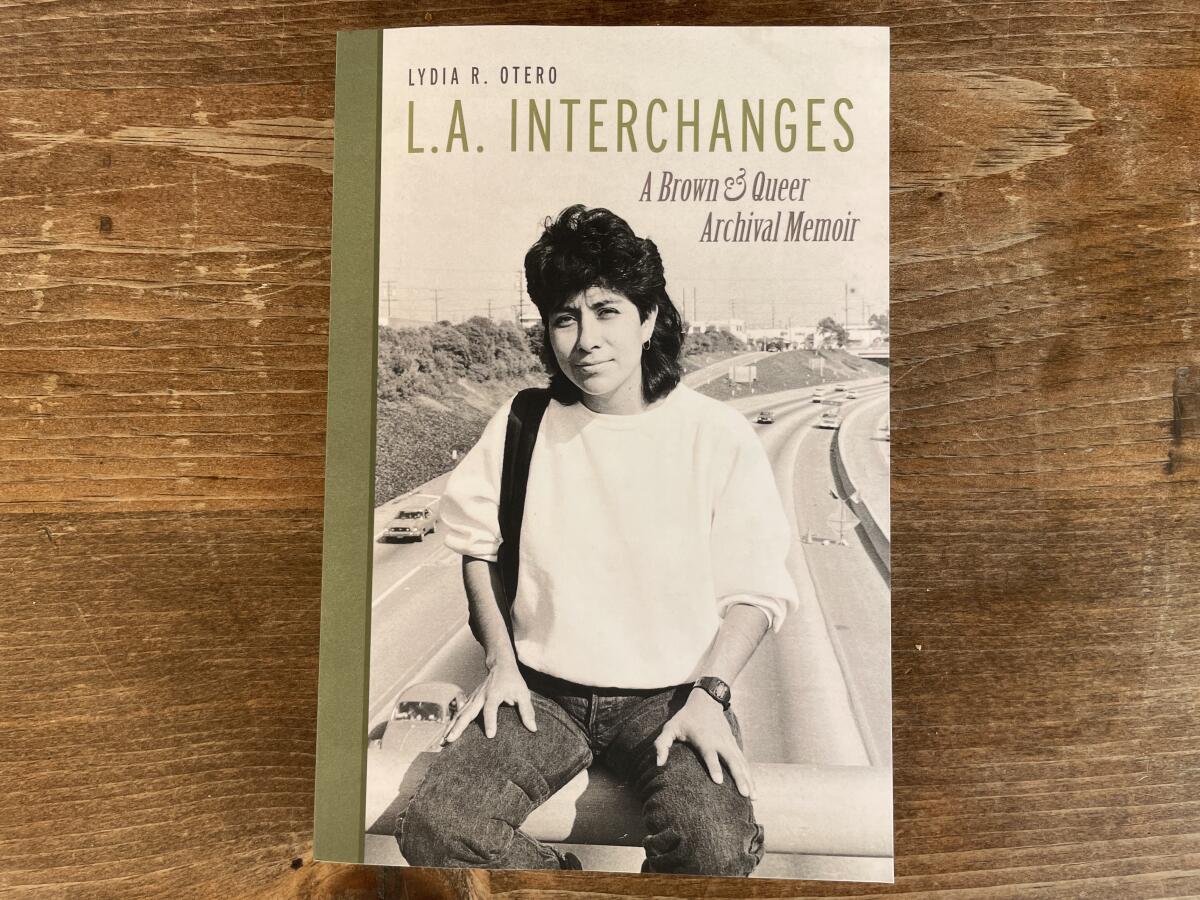

One of the people Schwartz thanks in his acknowledgments is Lydia R. Otero, a polymath if ever there was one: a union electrician who worked on the 105 Freeway and the first sections of the Metro line, a pioneering queer activist in Los Angeles, a historian of Mexican Americans in Tucson and a beloved professor at the University of Arizona.

Otero, who identifies as nonbinary, ties these disparate threads together in their taut, warmly told “L.A. Interchanges: A Brown & Queer Archival Memoir.”

They arrived in L.A. in 1978 from Arizona and plugged into an emerging Latino LGBTQ+ scene fighting for visibility among both fellow Latinos and queer folks. “L.A. Interchanges” intersperses personal memories with a much-needed roll call of bars, clubs, publications, organizations and individuals whose names still haven’t made it into mainstream LGBTQ+ histories of Southern California.

“My aim,” Otero writes in the intro, “is to portray queers of color as makers of history.”

The narrative is compelling enough, but just as important for Otero are the archives they kept all these decades later: fliers, articles, newsletters and especially photos that range from protests and conventions to one of Otero in a 1981 Dodgers World Series championship T-shirt, drinking a glass of milk and eating what appears to be a Ding Dong.

Activism is important, the author argues, but so is living a life of joy and remembering it.

“When I moved [to Los Angeles],” Otero concludes, “I considered it a place of possibility. It fulfilled my expectations and more.”

If that’s not the best summation of the California Dream, I don’t know what is.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.