Mocked, maligned and ignored, Cal-Mex dining is a testament to our state’s true history — and the food is glorious

Beans and rice with a chile relleno. A wet burrito. An enchilada.

The No. 3 or No. 15. Manuel’s Special. The Gloria.

El Cholo. Acapulco. Avila’s El Ranchito. Loud decorations. Humongous portions. Perpetual fiesta.

Casa Vega. Mitla Cafe. Paco’s Cantina.

After a while, your typical California Mexican restaurants seem to all blend into themselves like sour cream mashed into guacamole.

That might be your initial reaction to this week’s special package celebrating a style of food that Californians have enjoyed since the start of the state itself — and have taken for granted for far too long.

We tallied a list with scores of classic Mexican restaurants across the region. Here are our top picks.

In an era when regional specialties from across Mexico are available across Los Angeles and beyond, from high-end restaurants to street corners, why bother with places and platters that many eaters think of as little better than cheesy — literally — time capsules from a different California?

That’s how I felt about Cal-Mex food for most of my life.

When a white girlfriend introduced me to the cuisine at 18, at the just-shuttered Mexi-Casa in Anaheim, what she scarfed up and I picked at was as alien to me as a walk on the moon. In my 20s, I felt its garlic-laced flavors were an abomination to what “true” Mexican food was.

By the time I wrote my 2012 book “Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America,” I had developed a grudging respect for Cal-Mex’s role in popularizing Mexican food in the United States via national chains like El Torito and Taco Bell. But I still wrote that it was on its way out, a foodway favored only by middle-aged and elderly people who grew up with it or didn’t know any better.

Now, in my 40s, I can say such thoughts were a smug, stupid dismissal.

Cal-Mex is far more than nostalgia on a hot plate accompanied by chips and salsa. Sure, its hallmarks of taste and ambience — bowls of tortilla soup and massive margaritas, pork tamales with a solitary olive, guayabera-donning waiters and mariachi brunches — represent comfort and tradition that haven’t been seen as hip for decades.

But while numerous other culinary trends have come and gone, Cal Mex has not only remained but thrived, even as skeptics mocked and dismissed it and its kissing cousins, Tex-Mex and Sur-Mex, as something inferior. This very paper in 1991 let chefs who felt they cooked “real Mexican food” trash what The Times deemed “Blando-Mex.”

An exclusive behind-the-scenes look at Tito’s Tacos’ crunchy tacos, from the tortilla factory to the commissary kitchen to the actual restaurant.

Those supposedly “real Mexican” pioneers are long shuttered; one Blando-Mex spot named, El Tepeyac, remains as popular as ever.

In reality, Cal-Mex is a metaphor for our state itself.

Its history and resilience tells us where we came from, who we are and where we’re going — never static, perpetually underestimated, forever dynamic. Cal-Mex has always adapted to the times in a way few other culinary traditions have. This bedrock of California identity will never allow itself to be relegated to a museum, as much as haters might want to.

Most important? Cal-Mex food is good.

The American love affair with Cal-Mex began even before California became a state.

In “Two Years Before the Mast,” Richard Henry Dana Jr.’s famous 1840 account of his voyage on a merchant ship that sailed from his native Boston to California, he described a day off in San Diego where he feasted on a “regal banquet” of “baked meats, frijoles stewed with peppers and onions, boiled eggs, and California flour baked into a kind of macaroni.” Later on, Dana praised those frijoles as “when well cooked, ... the best bean[s] in the world.”

Newcomers embraced Cal-Mex in California’s first century like a religion. Partly that was due to the flavors: earthy and meaty and spicy. But by consuming this food, they also could consume a conquered land and make it theirs.

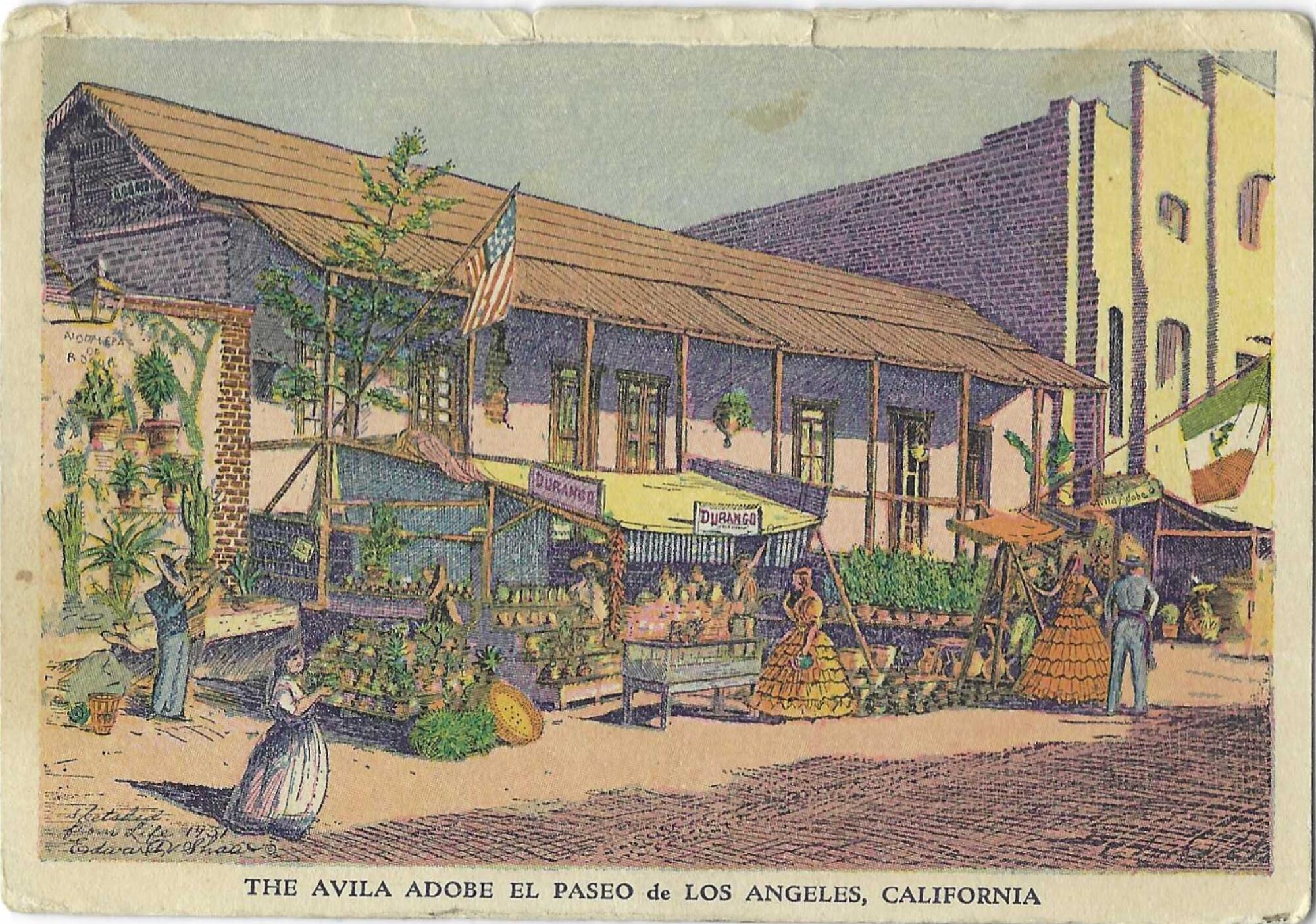

Well-to-do women held tamaleadas on fine china that the society pages of local newspapers breathlessly reported on — a typical dispatch appeared in an 1892 Los Angeles Times blurb that reported, “Mrs A.W. Patton entertained a few friends at a tamale party last Friday evening, which was a very enjoyable affair.” Charles Fletcher Lummis, the legendary antiquarian who was among the earliest chroniclers of Mexican food in American letters, published a cookbook at the turn of the 20th century composed mostly of Mexican recipes as a fundraiser to rehabilitate California’s missions. L.A.’s city fathers created an entire playground — Olvera Street — in the 1930s just to re-create what they insisted was a rapidly vanishing culture.

What was offered then — albondigas, picadillo and empanadas, among other treats — is familiar to us today, but not the name under which those eaters knew the cuisine as: “Spanish.” It was an ethnic label born from the decision of Californios who, when faced with eradication after the Mexican-American War, chose to identify with their Iberian ancestry instead of their Mexican heritage in order to survive in a new country that saw anything “Mexican” as suspect.

The choice made the food respectable to successive waves of non-Mexicans and survives in the anachronistically titled “Spanish” rice. But calling Cal-Mex food anything but Mexican created a false dichotomy that has plagued it for the last couple of generations.

Most Mexican migrants and their descendants who arrived after the 1960s have shunned Cal-Mex altogether under the idea that places that serve it are agringadas — whitewashed. Eventually, non-Mexican eaters believed this as well. Dishes like chile verde, taco salads and chalupas became relics as customers hungered for offerings that were more “authentic.”

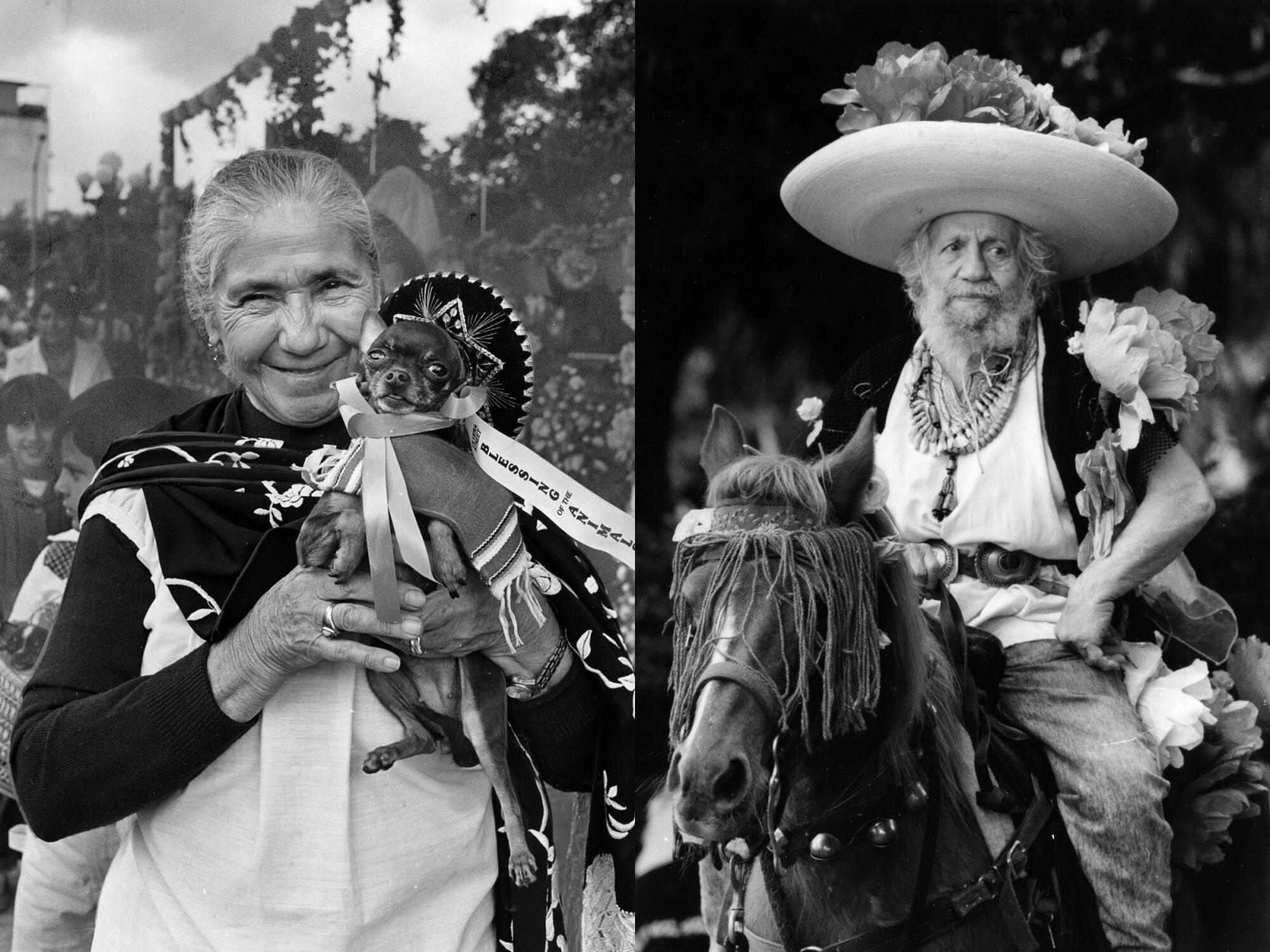

Such a characterization, though, erases the millions of Chicanos who consider Cal-Mex their heritage. In her recent book “A Place at the Nayarit,” USC professor and MacArthur grant recipient Natalia Molina describes such restaurants as “urban anchors” that allowed raza to publicly celebrate who they were in a society that otherwise rejected them, and gave them a place to hold banquets, gather for causes or just party.

Cal-Mex has always served as a platform to popularize “new” styles of Mexican food. Crispy and “soft” tacos, burritos, nachos, fajitas — all were once outsiders that found a welcome home on combo plates and weekend buffets. And if a meal could make it there, it could make it anywhere.

Consider the menus at El Cholo, the chain that will celebrate its centennial next year and is the second-oldest Mexican restaurant in the United States. I love to visit whenever possible, not just for its underrated meals but also just to read the entrees. They offer a timeline of Cal-Mex’s evolution — and show it has been at the forefront of trends more often than not.

Los Angeles’ Mexican restaurant chain El Cholo has dozens of employees in the ‘20-year club.’ Here are five of the longest-serving.

The oldest date on the menu is 1923 — El Cholo’s founding — and is next to its handmade flour tortillas, made from a recipe unchanged since then, even as many restaurants across Southern California are just upping their flour tortilla game. Chicken enchiladas made with blue corn tortillas date to 1985 and are a reminder that heirloom corn in stateside Mexican restaurants was first associated with Southwestern cuisine, not the milpas of central and southern Mexico the way it is today. The most recent date is 2019 for El Cholo’s Mexican chopped vegetable salad, which features kale, jicama and a citrus vinaigrette and is a reflection of demand for lighter, healthier options with “Mexican” flavors.

Does a dying cuisine evolve like this?

I used to go to Cal-Mex restaurants far more often. I’d haunt them as if they were on the verge of extinction, until I realized such desperation was unnecessary. Cal-Mex is all around us.

The Bob’s Big Boy in Downey serves delicious chilaquiles, which are now as much a breakfast staple in the Southland as hash browns and bagels. Birria de res — for most of my life offered only at weddings and quinceañeras of people hailing from Zacatecas — is so ubiquitous that Norm’s sells a version and the word recently entered the Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Costco now stocks michelada mixes created by the Lopez family — the siblings whose parents helped to introduce Oaxacan cooking to the United States through their restaurant, Guelaguetza.

Those treats are the latest generation of dishes assimilated into the Cal-Mex canon. There will be more. There will always be more.

So consider this package a guide to our state’s culinary soul. The entries share collective centuries of memories and represent only a slice of such places in Southern California (we didn’t even get to Cal-Mex spots in San Diego, the Central Valley and Sacramento, each with its own takes). There are hundreds, if not thousands, to explore.

Cal-Mex food is permanently on our state’s menu. We take a closer look at some of the cuisine’s beloved institutions in Los Angeles and the part they play in the city’s identity.

If you’ve been a skeptic, now’s the time to become a true believer. If you’re a longtime fan, now’s the time to return to your favorites. The pandemic sadly knocked out many long-standing Cal-Mex restaurants for good. Some of the older ones struggle to draw new crowds. Will they survive?

Cal-Mex has seen tough times before, and it always rebounds toward a better place. So try all of our recommendations and remember:

Cal-Mex por vida.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.