At most high school reunions, people talk about kids, spouses and jobs. But at a party for 1970s graduates of Lynwood High School, two women on the dance floor were talking homicide.

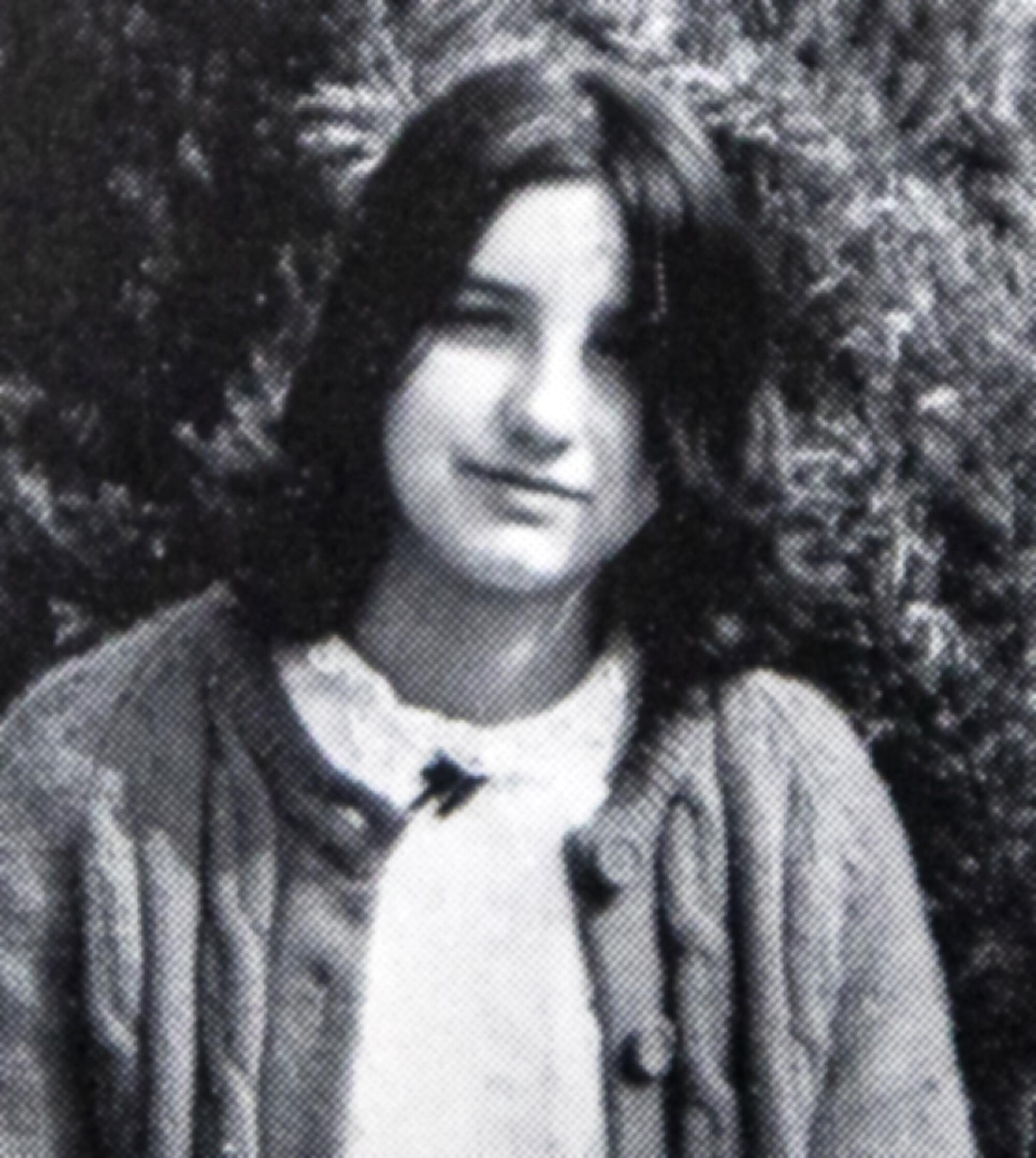

Rose Morales and Cheryl Sanchez Simmons had just learned that, when they were young, a girl their age had been strangled in their hometown. The killing of Jan Marsh, 14, had never been solved. And though the case had unfolded around them, neither woman had heard her story.

As a band played ’70s hits inside a hotel near Disneyland, Sanchez Simmons danced her way over to Morales and said: “We can’t let this go. We have to find out.”

That vow launched Morales, Sanchez Simmons and fellow Lynwood native Tina McKillip into a years-long effort to seek justice for a classmate they had never known.

Helped by their deep roots in the small city in southeast Los Angeles County and their polite refusal to take no for an answer, the three women have tracked down hundreds of pages of old records, spoken to dozens of people and built their own version of a “murder book,” laying out the suspects and evidence in Jan’s case.

Solving a killing that went cold a half-century ago is a daunting prospect for anyone, let alone amateurs. And the trio is in a race against time as the people who knew Jan start to die.

But the women refuse to give up hope. When you get old, they believe, you want to confess the sins of your youth. Someone, somewhere, must know something.

“Jan was a Lynwood girl,” Sanchez Simmons said. “And Lynwood girls look out for each other.”

On Nov. 4, 1969, a student walking toward Lynwood High discovered Jan’s body in the side yard of a bungalow on a quiet suburban street. She was face down in the grass, a long-sleeved shirt tied around her nose and mouth.

An autopsy concluded that Jan had been killed overnight. The medical examiner found no alcohol or sedatives in her body.

From the start, the case perplexed the Lynwood Police Department. Detectives had a wide circle of potential suspects. But they found no link between Jan and the house where she was found, no evidence of where she had been killed, and no clear story of how she had died.

Weeks wore on with no arrests. Jan soon vanished from the headlines, and from the town’s memory.

Morales, Sanchez Simmons and McKillip had no experience with criminal investigations when they decided to look into Jan’s death.

Sanchez Simmons, 66, works for Orange County’s public health authority. Morales, 68, works for a logistics company in Long Beach. And McKillip, 64, is a researcher who helps adoptees find their birth parents.

The women graduated in different years, and their lives had branched off. Sanchez Simmons built a life in Florida, McKillip married a longshoreman in Long Beach, and Morales stayed local.

When Sanchez Simmons moved back to Southern California a decade ago, she started seeing Morales at lunches, parties and the Old Farts Picnic, an annual bash for Lynwood alums at a local park. Neither knew McKillip well.

A few months after Morales and Sanchez Simmons decided to look into Jan’s case, McKillip saw a Facebook post commemorating Jan on the 50th anniversary of her death.

“Still no information, still a mystery,” wrote a childhood friend. “This could have happened to any of us.”

McKillip quickly responded, offering to find Jan’s death certificate during her next trip to the cavernous building in Norwalk that houses Los Angeles County’s vital records. Her interest felt like kismet to Sanchez Simmons and Morales. The women joined forces.

There is no manual for cracking a cold case. So the women started with a familiar place: the library. After work and on weekends, they took two-hour shifts on the microfilm reader at the Norwalk branch, slowly scanning through dozens of editions of the Lynwood Press, the Long Beach Independent and other local newspapers from 1969 and 1970.

“I don’t think we even knew what we were looking for,” McKillip said. “Sometimes, you just have to look.”

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

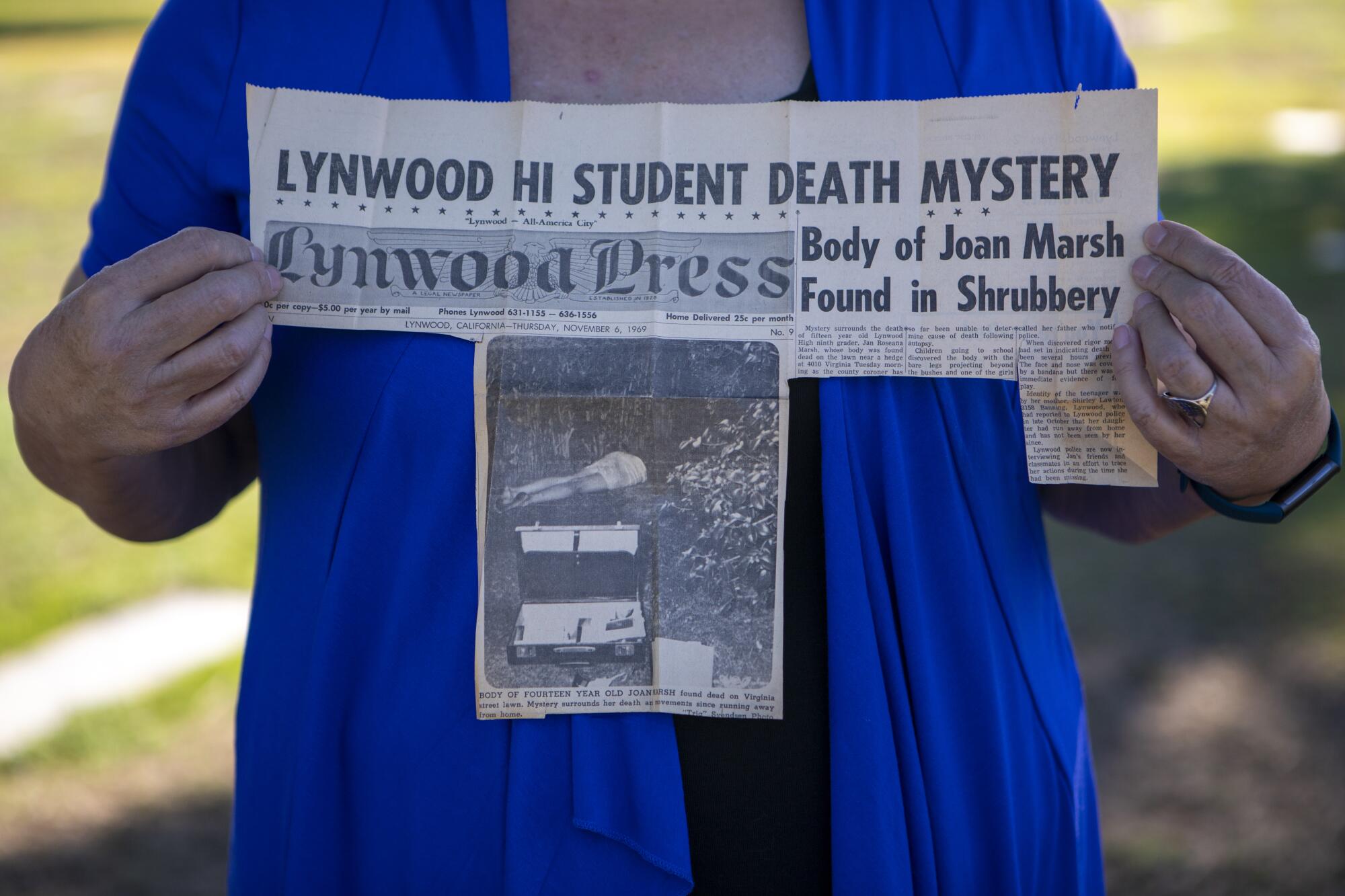

When Jan died, Morales was 14, Sanchez Simmons was 12, and McKillip was 11. Her killing made headlines, but their families shielded them from the news. The news stories from 1969 showed them just how callously Jan had been treated in death.

Police asked Jan’s best friend, then 13, to identify her body. The first story about the killing in the Lynwood Press mistakenly called her Joan. And the newspaper ran a photo of her body on the front page.

“When I first saw her on that lawn, the hair on the back of my neck went up,” Morales said. “I know it was a different time, but really? You’re going to put the body of a teenage girl on the front page?”

The newspapers provided a rough who’s-who of Lynwood police officers who worked on Jan’s case and others around the same time. The trio started contacting them by phone and Facebook Messenger, using a variation on the same theme each time: “We’re doing some research on Lynwood, way back when.”

They printed business cards that read “California Girls Investigations.” The “O” in California is a magnifying glass with long eyelashes, a nod to Morales’ signature makeup.

They settled into an investigative rhythm. McKillip, a genealogical researcher, could track down old records and navigate arcane databases. Sanchez Simmons, detail-oriented and determined, handled their correspondence and compiled their evidence. Morales, chatty and charming, started working the phones. For safety, she used a burner phone and, sometimes, a fake name: Nan Werd. (That’s short for Nancy, and Drew spelled backward.)

‘I don’t think we even knew what we were looking for. Sometimes, you just have to look.’

— Tina McKillip

With the world all but shut down in spring 2020, the women started spending hours together on Zoom in their pajamas, drinking wine and talking over the case. They also compared findings in a Facebook chat called “the Snoop Sisters,” named for the 1970s television show about two sleuths of a certain age.

They quickly realized that the Lynwood of their childhood, which called itself “the All-America City,” had a seedier side.

Jan’s father abandoned the family when Jan was 2, her sister was 7 months old and her mother, Shirley Lawton, was pregnant, divorce records show.

By 1969, Jan was the eldest of five. The family of seven lived in a two-bedroom apartment in a bungalow court near the railroad tracks. Lawton worked nights at the Continental Can factory in South Gate.

Jan, always stubborn, fought often with her mom as she entered her teenage years. She started climbing through a window and sneaking out at night to go to parties or wander the neighborhood alone.

“You could clearly see that there was something strange going on at home,” said classmate Johanna Van Der Linde-Rosales, 68, in an interview with The Times. “Jan didn’t really talk in detail about it, but one could put two and two together.”

Her mother sometimes invited Jan in for dinner or chatted with her on the sidewalk. But that was the exception in Lynwood, Van Der Linde-Rosales said.

“It reminds me of a caste system, the way people were,” Van Der Linde-Rosales said. “You have this family with a girl who’s running away, who’s getting in trouble. The mom has all these kids. And everybody brushed them aside.”

After a fight with her mother, Jan ran away in fall 1969. Lawton reported her missing to police on Oct. 29. Jan came home once more, to retrieve a makeup bag.

She attended a packed Halloween party. On a Sunday night, she went to the fall carnival in a downtown park, mobbed with kids eating popcorn and riding the Tilt-O-Whirl. She was seen at a pizza parlor Monday night. Her body was found Tuesday morning.

By the time McKillip, Morales and Sanchez Simmons learned of Jan’s death, her case had been cold for 50 years, and the police department that had investigated it no longer existed.

In 1977, Lynwood’s City Council joined a wave of suburban cities contracting out municipal services such as law enforcement and trash pickup. The city dissolved its Police Department, hired the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department to oversee public safety and transferred its investigative files — including cold cases — downtown.

The women asked the Sheriff’s Department for access to the police reports about Jan’s death. The department denied the request, saying the case was still active.

They had run into a frustrating Catch-22 for amateur sleuths: Cases that haven’t been solved are still considered open, even if they aren’t being actively investigated. And in California, records from open cases can’t be released to the public.

The women needed the files. They just had to find another way in.

Their luck turned when Sanchez Simmons contacted a former Lynwood police officer named Bill Hefley.

“Dear Mr. Hefley, I understand that you used to be a police officer around 1973 in Lynwood, CA,” Sanchez Simmons wrote in a Facebook message. “I am doing research into a murder that you may have investigated.”

Weeks went by. Then Hefley responded: “I would love to talk to you.”

Hefley had been a rookie officer when Jan was killed and oversaw her cold case as a detective in the mid-1970s. He had quit policing years earlier and left California. But he told Sanchez Simmons that he might still have some Lynwood files in his attic.

Two plain white envelopes from Hefley arrived at Sanchez Simmons’ house about a week apart in 2020, containing two police reports from the investigation into Jan’s death. Though the women didn’t have access to much of the case file, they had enough to start building a web of potential suspects.

Jan had hung out with a rough crowd of guys who were well-known to the cops. Some reportedly had ties to a Long Beach motorcycle gang called the Devil’s Disciples.

Few came up in Google searches. Many were too old — or had been dead too long — to leave a digital footprint. So the women worked the case the old-fashioned way: Digging through old records and calling the former bad boys of Lynwood, now in their 60s and 70s.

‘These guys are bad on another level. How did she get tied up with them?’

— One man told amateur sleuth Rose Morales

Armed with a list of names, Morales went to Hosler Middle School in Lynwood, where she told an employee that she was looking for childhood photos for a birthday party. She couldn’t find the men’s names in the years near Jan’s — suggesting, she thought, that Jan’s guy friends were not only unsavory, but also a few years her senior.

The trio pieced together a picture of Jan’s social circle: guys in their teens and 20s who drank, smoked and had sex with teenage girls, sometimes partying at a gas station on Atlantic Avenue or in an old boat parked outside.

“These guys are bad on another level,” one man told Morales. “How did she get tied up with them?”

Several had been seen at a Halloween party with Jan a few days before her death. One student told police that “one of the guys at the party had snuffed Jan.”

The women narrowed in on a 17-year-old boy named Kenneth Labron Evans. According to police, Evans walked into Mr. B’s Liquor Store in Compton three days after Jan was found dead, bought two Cokes and told the clerk that someone had “strangled her with a T-shirt.”

Evans also told a young couple, who contacted the police, that he had been “going” with Jan. He said he had been with her the night she died and slapped her during a fight, leaving a hand print, but “took off” before she was killed.

Evans sat for a polygraph, police wrote, and passed every question but one: “Concerning Jan Marsh on Monday night, were you with her when she died?” A police report said the polygraph operator was “unable to tell” whether Evans was truthful.

In 1975, Hefley ran into Evans at 3 a.m. and asked him about the killing. He wrote in a subsequent report that Evans, “in a very slurred voice,” responded: “I might know who did it, but I’m sure not going to tell you.”

The next morning, Evans told Hefley he couldn’t remember anything, according to a summary of the interrogation. He added: “I sure wish I hadn’t ate all that dope when I was young.”

Another suspect, Hefley said, was an employee for a local utility company, a man in his early 20s who ran in the same circles as Jan and left town shortly after her death.

The women were also intrigued by Danny Montgomery, a 19-year-old repo man, who Hefley said was a confidential informant for the Police Department’s vice squad. Montgomery had lent Jan his shirt at the carnival a few days before her death. She was wearing it when her body was found.

Don Meyers, another guy in the group, was convicted in 1973 of bludgeoning a junior high math teacher to death. The victim’s body had been covered with a blanket — not unlike Jan, the women thought, whose face had been covered with a T-shirt.

The women had long thought that Lynwood police hadn’t tried very hard to solve Jan’s case. Maybe a cop wanted to protect an informant swept up in a slaying. Or maybe Jan’s death was just seen as the kind of thing that happened to a runaway teenager who partied with men.

Hefley told The Times that he thought detectives had worked Jan’s case doggedly. Of the dozen or so cold cases under his purview, he said in an interview, Jan’s file was “the thickest one in the entire bunch.” He had never forgotten it.

Finding an answer was a long shot, he thought, but not impossible. Convincing a district attorney to file charges, and then getting a conviction, would be much harder. The case was already slippery in 1969, with suspects who were unreliable narrators, their memories fogged by drug use and drinking.

“Some of those people knew something, but they just couldn’t retain it long enough to talk to us,” Hefley said.

A year into their investigation, the women sat down with a cold-case detective at the Sheriff’s Department. The women brought their notes, and the detective brought the “murder book” from Jan’s case, a three-ring binder with a 6-inch stack of interviews and reports. He wouldn’t let them read it.

“I think he thought we were old ladies who were going to make a bit of a fuss, and then we were going to go away,” Sanchez Simmons said.

They talked for several hours, cautiously circling each other, discussing theories and suspects. The detective told them the identity of a man described in police reports only as “Indian Joe.” (He’d moved to Fresno County and become a minister, the trio later learned.)

The detective also showed them the crime scene photographs. The black-and-white images showed Jan’s body sprawled across the grass, her slim arms akimbo, the soles of her feet dirty.

Seeing the photos felt like a test of whether they were squeamish or serious, McKillip said, and she “decided to play it up a bit.” She steeled herself, picked up a photograph of Jan’s body and said to Morales, “Hand me that magnifying glass.”

The women had hoped a detective would start investigating Jan’s case after their meeting. But no one did.

It’s the hard reality of many cold cases in Los Angeles. The Sheriff’s Department has about 5,000 unsolved homicides dating back decades, said Lt. Hugh Reynaga, who runs the cold-case team. Thousands more are under the purview of the Los Angeles Police Department.

The Sheriff’s Department has 10 part-time investigators for cold cases, he said, and five investigate homicides.

A suspect in the 1979 cold case murder of Patricia Carnahan in El Dorado County, has been arrested after investigators found a DNA match for an unrelated crime in Washington state.

“We have to triage the unsolved cases that we have and put the ones that are most solvable to the front,” Reynaga said.

Frustrated and disappointed, the women pressed ahead. For Jan, they thought, they had to.

They told only a few people what they were up to. When one former classmate learned the full story, he delightedly referred to them as the “Lynwood Detective Chicks” — the LDC, for short.

In 2021, Morales reached the childhood friend of Jan’s who had identified her body. She said that days later, someone poured gasoline underneath her bedroom window and set it on fire. The arson attempt left her rattled. It had been 52 years, and she still didn’t like to talk about it. And she didn’t want her name used.

Sanchez Simmons also built a relationship with Jan’s half-sister, Patricia Podolak. She sent a Christmas card, a photo of fresh flowers on Jan’s grave and a message that her sister had not been forgotten.

“At first I was very suspicious, like, why are you doing this?” said Podolak, 60, who lives in southwest Iowa.

But Podolak came to see the women as an answer to her prayers. She had never stopped wondering what happened to her big sister, who died when she was 7.

She went back again and again to a hazy memory from around the time of Jan’s death. She sat in the back seat of the family car as her mom talked to a tall young man with dark hair and stitches in the back of his head.

“I remember him saying to my mom that he had tried to stop them, and it didn’t work,” Podolak said.

She remembered piping up, asking him where her sister had gone. That was all she could recall.

The Lynwood women were running into another frustrating, all-too-common element of cold cases: Childhood memories, even from the killing of a loved one or a friend, grow murky over time.

At least, they thought, there was DNA testing, which wasn’t used widely by police departments until decades after Jan’s death. Lynwood police had preserved the clothes she was wearing and the shirt wrapped around her face. The medical examiner also noted that he took oral and vaginal swabs during the autopsy.

Any of those items could point to a culprit or narrow the list of suspects. The trio just had to wait for the Sheriff’s Department to find the box of evidence.

They kept digging. McKillip found the prison records for Meyers, who had been convicted of murder in 1973. He was released from prison in the 1980s and moved to Bullhead City, Ariz.

During one late-night call, the trio debated whether to make the five-hour drive to meet him — and maybe, afterward, dig through his trash for a straw or a tissue with a sample of his DNA.

They decided not to. They were still hopeful the Sheriff’s Department would launch a new investigation, and wary of tainting any criminal proceedings.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

By then, Lawton, Jan’s mother, was in her mid-80s and frail. Knowing they might not have another chance, Sanchez Simmons and her husband visited Lawton and Podolak in southwest Iowa. They made a two-day detour to Council Bluffs during a road trip to a family reunion in South Dakota in 2021.

The mother, the daughter and the sleuth met in the sitting area of Sanchez Simmons’ hotel suite and talked as Sanchez Simmons’ husband recorded a video.

They learned that Jan’s full name was Janansull, bestowed by her grandmother in the hospital just after her birth. When kids at school started teasing her about her name, she shortened it to Jan, Lawton recalled.

Her eldest daughter was spirited, beautiful, stubborn. Lawton was worried that she had fallen in with a bad crowd. She refused to let Jan go out the night she ran away.

Lawton said in a matter-of-fact tone that she had tried to suppress her grief over her eldest child’s death. Jan was the love of her life, she said. But she was working full time, with four other children to look after.

“Every once in a while, I think about it, think about her,” said Lawton, 85. “It’s not that I forgot. I just don’t try to remember.”

The interview was a reminder of the stakes: not just for a girl whose murder was unsolved, but also for her family, still waiting for answers after more than five decades.

The women pushed forward, but progress was slowing. They had hit the part of the investigation that doesn’t make the true-crime specials: the frustration, the waiting, the dead ends.

McKillip confirmed that two of their suspects had died: Montgomery in 1993, Evans in 2012. She also learned that Meyers had died in Arizona in 2022. The Sheriff’s Department had not contacted him. McKillip said she deeply regretted not acting on her impulse to drive there, interview him and dig through his trash.

Lawton died in 2022. Until her death, she had saved a pair of Jan’s jeans, covered in doodles in blue and black ink.

‘It’s not that I forgot. I just don’t try to remember.’

— Shirley Lawton, Jan Marsh’s mother

Their biggest blow came from those they hoped would be their allies: the Sheriff’s Department.

As far as the women knew, the department hadn’t done much work on Jan’s case. But they still hoped that DNA testing could help.

Reynaga told them that the box of evidence from Jan’s case was missing. Without it — without the clothes, the swabs, the shirt tied around her mouth — there could be no forensic testing.

There’s no way to know what happened to the box, Reynaga told The Times. It may have been misfiled or mislabeled in the department’s cavernous evidence storage.

The women were crushed.

“We served up people to them on a platter, and they wouldn’t even do interviews,” McKillip said. “Now they’ve lost everything: the swabs, the clothes. It’s just unacceptable.”

They couldn’t help wondering whether other cold cases had missing evidence boxes too. Frustrated and disappointed, the women sent tart letters to the five Los Angeles County supervisors, then-Sheriff Alex Villanueva and Dist. Atty. George Gascón.

“It is deeply discouraging to see neighboring counties solving cold-case murders on a regular basis while one of the largest departments in the country can’t even find Jan’s evidence box,” they wrote. “So much for L.A. justice.”

Weeks after The Times asked the Sheriff’s Department about the missing evidence, cold-case detective Shaun McCarthy went on a true-crime podcast to discuss Jan’s case. Without the interest from the Lynwood women, he said, he probably wouldn’t have looked into it.

He and Reynaga had “searched and searched and searched” for the box of evidence. With “brutal honesty,” McCarthy said, “we don’t know where it’s at.”

The case is not closed. But the odds of solving it are low, he said. With forensic evidence, maybe things would have been different.

After their series of setbacks, the women got braver. When they learned that an informant had contacted Lynwood police in 1975 to say that he’d overheard two men talking about who killed Jan, Morales worked up the courage to call his family. She learned he was hospitalized in the intensive care unit. He died hours later.

She called Sanchez Simmons and McKillip to break the news. Then, she said, “I had a martini when I got home.”

She also began trying to contact the utility worker who had left town suddenly after Jan’s death. In late May, after she sent him a letter, he called her back. In a soft-spoken Arkansas drawl, he said he had no memory of Jan, or of her death.

It defied belief for Morales. “If somebody died, the way she did, and he was hanging around with all those people — how could you forget that?”

She’ll call him again.

The women have found two other cold cases from Lynwood to investigate.

Those, they said, are next on their list.

Local sleuths help find a suspect in gay porn actor Bill Newton’s murder. His dismembered head and feet were found in a Hollywood dumpster in 1990.

Times news researcher Jennifer Arcand contributed to this report.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.