The first time most people in Los Angeles heard of gay porn actor Billy London — a.k.a. Bill Newton — was when his head and feet showed up in a dumpster.

Newton’s murder in the fall of 1990 rattled the close-knit gay enclave of West Hollywood, even amid the unrelenting wave of young men dying from AIDS. Homicide detectives with the Los Angeles Police Department diligently pursued the case but kept running into dead ends in a community with good reason to distrust them.

For the next 30 years, Newton remained one of L.A.’s many unavenged souls. The LAPD’s interviews and investigative notes went cold. His murder — easily painted with broad strokes in film noir gray — became an unfair allegory about Hollywood’s gay underbelly and the supposed wickedness of sex work.

But in a twist most true-crime fans could only dream of, a team of amateur internet sleuths has helped crack the case.

On Monday, a pair of cold-case detectives confirmed they had secured a confession in Newton’s murder. His alleged killer, they said, was another former gay porn actor in West Hollywood. The suspect is serving a life sentence in prison, convicted of abducting and brutally killing another gay man years after Newton’s murder.

The suspect was first identified as a person of interest in Newton’s murder not by detectives but by Clark Williams, a stay-at-home dad turned empty-nester. Williams became obsessed with the case after seeing so many similarities between the dead man and himself: He and Newton were born just a week apart in 1965 in the same part of northern Wisconsin, where homophobia was rampant, and each had fled to a bigger city to find a better life.

How Williams figured it all out, said lead Det. John Lamberti, was amazing.

“I like to think I’m a pretty good detective — been doing homicide for a while — and I never would have made this connection,” Lamberti said. “Not in a million years would I have come up with what Clark came up with.”

“The hair on the back of my neck stood up,” Williams said of the moment it all clicked. “I’m like, ‘What the f—? How is this possible?’”

A true story of love, deceit, denial and, ultimately survival. The hit L.A. Times podcast is now a Bravo TV show.

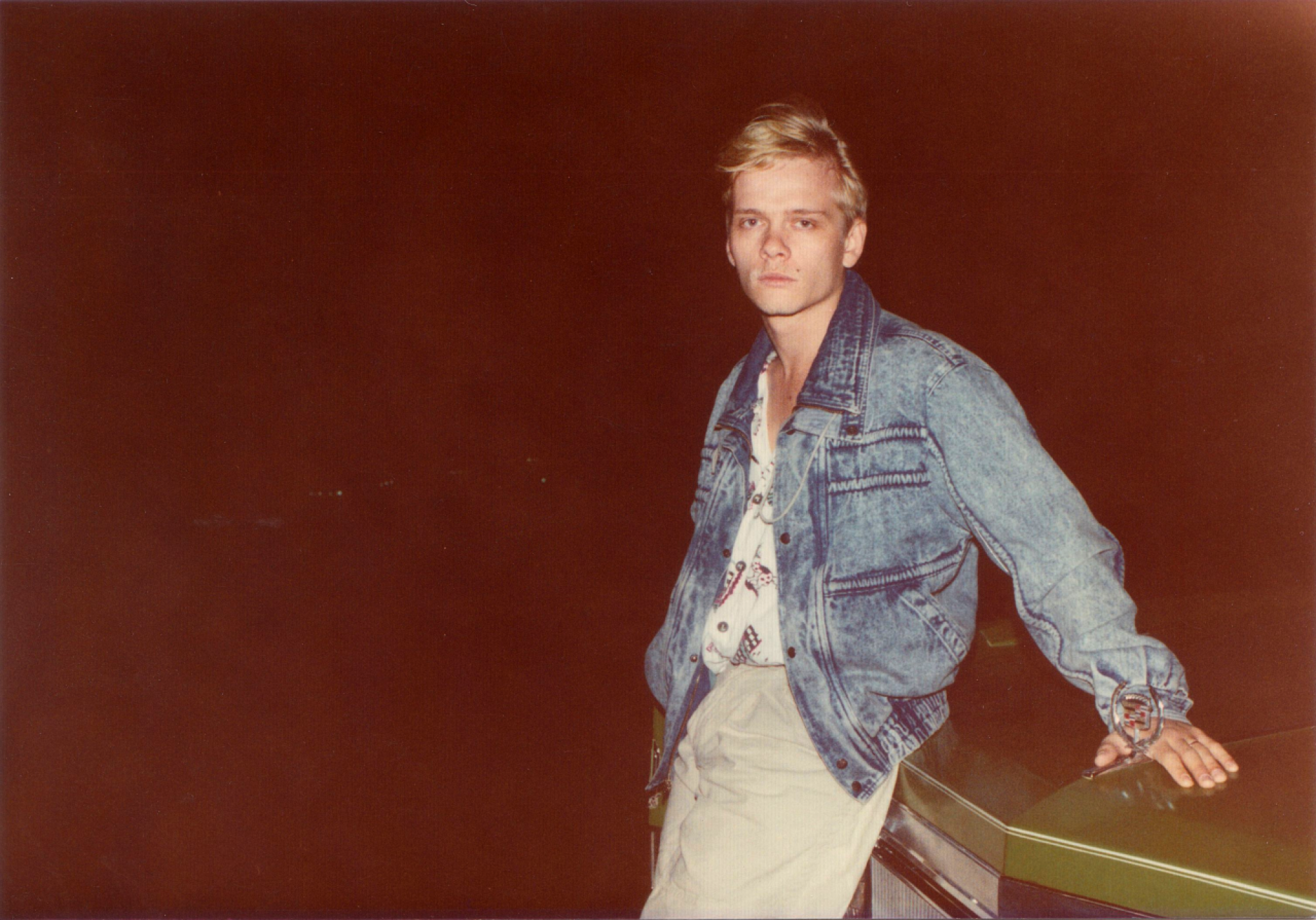

Billy in Boystown

Newton had a “sort of Hollywood, blue-eyed, blond-haired, boy-next-door” appeal that people adored, said Marc Rabins, Newton’s on-again, off-again boyfriend. “He was devastatingly handsome in my eyes, and in a lot of people’s eyes.”

He’d also had a tough childhood.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Newton had bounced around Wisconsin with his mother until he was 16, when he ran away to live with his father. But when the teenager arrived, his father “opened the door and said something to the effect of, ‘You’re no faggot son of mine,’ and slammed the door,” Rabins said.

Their father “was a man’s man,” said Michele Oliver, Newton’s younger half sister. “His expectations for Bill were too high.”

From that point on, Newton was a runaway and on his own, eventually landing in West Hollywood. Rabins met him one night at the Hollywood Spa, a gay bathhouse where Newton was working and Rabins was judging a beauty contest for Data-Boy, a local gay magazine.

Rabins and Newton were together on and off for the next few years. Rabins produced gay porn videos, and Newton started working with him.

Newton was sweet but vulnerable, creative and smart; he wrote poetry and dreamed of starting a business offering interior design, artwork and writing for hire. He wanted to call it Isms because, he told Rabins, “everybody has -isms.”

“I can’t tell you how many movies we did in our apartment — that we shot in our apartment — where he would redecorate the rooms [so that] it didn’t look like we were shooting in the same place,” Rabins said with a laugh. “I would say, ‘It’s great. Every time we shoot a movie, we get to redecorate the place!’”

Newton, Rabins said, was always quirky and “lighthearted.” He once dyed the roots of his naturally blond hair a darker color. A puzzled Rabins asked why.

“You know, everybody thinks blonds are dumb,” Newton replied, “so I figured if I dyed my roots, I could just claim my hair is bleached.”

The pair also partied hard and did methamphetamine on the weekends, Rabins said, and he often worried that they did too much.

By October 1990, the two were living apart again. Newton, then 25, was planning on moving temporarily to Las Vegas to live with Oliver while he helped his mother settle into a new place there.

“He was tired of L.A.,” Oliver said. “He just needed a mental health break.”

Subscriber exclusive: Of the many mysteries that surround the Golden State Killer, one of the most consequential is exactly how authorities caught Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. four decades after his murders began.

One night, after shooting a video and going to dinner, Rabins dropped Newton off at the home of a few friends, where he was staying.

Two days later, Newton’s head was found in a dumpster in an alley off Santa Monica Boulevard, not far from La Brea Avenue, by a transient digging in the trash.

Retired LAPD Det. Wendi Berndt, who was assigned the case, still remembers that day as hot and humid, the heat “just packing down” on the taped-off crime scene. The sun was shining “very, very bright” — including on Newton’s handsome face and bright blue eyes, which stared back at her from the dumpster.

“It was just so heinous in my mind that something like this could happen, and it didn’t matter to me that Bill was gay or that he worked in the pornography field,” Berndt said. “It was a murder that I felt was my responsibility to solve, so I put everything into this case.”

Reviving the case

Rachel Mason learned of Newton’s murder by accident.

She was working on a documentary in 2017 or 2018 about Circus of Books, the adult bookstore on Santa Monica Boulevard where her parents had spent years selling porn and LGBTQ literature.

She wanted to show the real lives of the young men in the magazines and films on her parents’ shelves, people who were also their friends and neighbors. So she met with local writer and activist Mike Szymanski — a.k.a. Mickey Skee — to go through his old collection of West Hollywood photos.

“I needed something that was personal,” Mason said. “I wanted to pay homage to the guys that I grew up seeing, who were these beautiful, real people.”

During their search, a news article from 1990 fell out of one of Skee’s notebooks, and Mason said the headline leaped out at her: “Cops Have No Clues in Grisly Killing of L.A. Porn Actor.”

“What is this?” she said.

“Oh,” Skee replied. “That’s this really crazy story.”

Mason said she was intrigued but had no immediate use for the tale. But after she wrapped the Circus of Books film and began looking for her next project, it “kept coming to mind,” she said.

She started to look into the case.

She wasn’t the only one.

Authors Christopher Rice and Eric Shaw Quinn, who run a podcast called “The Dinner Party Show,” began their own dive into Newton’s murder about the same time. They put out a call for tips from the community, conducted interviews and in October 2020, just a few days before the murder’s 30th anniversary, broadcast an episode about it.

In the podcast, Rice and Quinn talked about how hard it must have been for the gay community to deal with such a gruesome murder of one of their own, especially when AIDS was already killing young men in the community at an astounding rate.

Rice also shared what seemed like a potentially significant new break in the case. He had received a tip from a listener who claimed to have met Newton at Rage Nightclub the evening before his head and feet were found.

The tipster said he saw Newton leave the club with a man who looked exactly like Jeffrey Dahmer — the Milwaukee serial killer who butchered and had sex with the corpses of 17 men and boys between 1978 and the early 1990s.

The LAPD’s Lamberti did not know about Rice and Quinn’s podcast when it aired. But shortly afterward, he happened to pick the cold case back up, and he was struck by the amount of work his predecessors had done, to no avail.

To an early love interest, Joe DeAngelo was energetic and worldly. Now, nearly 50 years later, he stands accused of an extended spasm of violence — home invasions, rapes, murders — in the 1970s and ’80s.

Materials from cold LAPD homicide cases are usually contained in a single three-ring binder, 3½ inches thick. But the materials about Newton’s murder — much of it compiled by Berndt — filled six, each crammed with meticulous notes, theories, interview transcripts and photographs.

“They investigated the hell out of this case,” Lamberti said.

But they’d never identified a real suspect.

Lamberti decided to plug Newton’s name into Google “to see what was out there,” he said. One of the results was the podcast episode in which Rice and Quinn discussed the tip they’d received about a Dahmer look-alike.

“That caused me to crack open the file and look at it a little more deeply,” Lamberti said.

He contacted Rice and Quinn, and Mason as well, and they all started sharing information. They also got in touch with Newton’s family, which supported reviving the case.

“It did bring back a lot of emotions,” said Oliver, 57, who was just six months younger than her brother. “But at the same time, I thought that this would be good ... to get something out there that showed that we hadn’t really forgotten about Bill.”

When Mason put out her own request for tips, one of the people she heard from was Williams, the man who, like Newton, was from Eau Claire, Wis. He said he might be able to fill in gaps in Newton’s life story, possibly by explaining what it was like growing up in their hometown.

“It’s strange how my life seemed to shadow Billy’s,” Williams wrote.

The team of sleuths had formed.

Digging through time

In December 2021, Williams and his husband were living in Sherman Oaks. Their daughter had gone off to college. Williams said he “wasn’t sure what I was going to do with the rest of my life.”

“Then Billy Newton showed up.”

Williams was looking at a Facebook group called The History of Gay Wisconsin when he noticed a post about Newton’s murder. Once he realized how similar their early lives were, he couldn’t stop thinking about the case.

“Something was propelling me, moving me to just get involved in whatever capacity that I could,” Williams said. “What I really wanted to do was to help tell Billy’s story, because I think he reflected the lives of so many young gay men and teenagers who came up in that time.”

Williams emailed Mason, started getting more involved in the case, and at some point zeroed in on another — perhaps the first — local sleuth who had worked on it: Rick Paskay.

Paskay, who has since died, had operated a skate shop in West Hollywood but also dabbled as a private investigator and had devoted a large amount of time trying to solve Newton’s murder — including by working closely with Berndt, feeding the detective tips about people in Newton’s orbit.

Sometimes people who buzz around police investigations end up being involved themselves, and Paskay’s deep interest in the case always made Berndt nervous. He seemed “forthcoming and personable,” she said, and helpful. But what if there was something she was missing about him?

“It never left my mind,” she said.

Williams found Paskay’s involvement interesting too — and even more so when he discovered a few months ago that Paskay not only was a local businessman but had worked as a gay porn producer under the alias Richard Lawrence at the same time Newton was in the industry.

“I decided to do a deep dive,” Williams said. “Who was Rick Paskay?”

Williams started reviewing the credits from Paskay’s films for the names of actors, producers and editors so that he could then “try to find anyone who was alive to talk to them about their recollections.”

He was focused mostly on films made around the time of Newton’s murder, including one titled “The Devil and Danny Webster,” which promoted a brand new actor named Billy Houston as starring in the title role.

Williams began researching Houston, spending “hours and hours” digging through old newspaper records for any clues about who he might be — until he found the one that gave him chills.

It was a 2007 or 2008 article from Oklahoma about a self-proclaimed white supremacist and skinhead named Darrell Lynn Madden. Madden had pleaded guilty to killing a gay man in Oklahoma named Steven Domer and another man named Bradley Qualls, who had been Madden’s accomplice in Domer’s murder.

Madden and Qualls had gone out with the intent to kidnap a gay man as part of a gang initiation of Qualls into the Chaos Squad Skinheads, a white supremacist group, according to accounts Madden provided to law enforcement and others. They pretended to be sex workers, lured Domer to a secluded area, restrained him in his own vehicle, then drove around beating him before strangling him with a coat hanger, according to Madden’s accounts. They then dumped his body into a creek.

Madden later shot and killed Qualls, fled that scene and was shot by a police officer before being taken into custody.

At the bottom of the article Williams had found, it said Madden — whose eyebrows had been shaved off and replaced with the tattooed words “SKIN” and “HEAD” — had formerly acted in gay porn.

Madden’s stage name: Billy Houston.

“It was a coincidence that I just could not ignore,” Williams said.

Edward Humes, author of ‘The Forever Witness: How DNA and Genealogy Solved a Cold Case Double Murder,’ discusses the implications of forensic genealogy.

Williams dug up criminal records that placed Madden in L.A. around the time of Newton’s murder, which was also a time when skinheads were causing widespread problems across Southern California.

The idea that Madden could have been part of the gay community while running around with West Hollywood skinheads presented what Williams viewed as “a psychology that was quite dangerous.”

He kept digging.

Author David McConnell had spoken to Madden for a book he’d written called “American Honor Killings.” Williams ordered the book, went through it with a yellow highlighter and was shocked, again.

Madden had not only confessed to killing Domer in Oklahoma City, according to the book, but allegedly to killing in L.A., too.

Williams said he “leaped out of [his] bed and stood silent for a moment” after reading that line — scared and not sure what to do.

“I realized at that moment that I was in over my head,” Williams said, “and that I needed to get this information as soon as possible to Det. Lamberti.”

Securing a confession

In the preceding months, Lamberti had spent a significant amount of time looking into the podcast tip that Newton had left Rage with a man who looked like Dahmer.

The idea that the serial killer, a.k.a. the Milwaukee Cannibal, could have had something to do with the case wasn’t new.

Within the LAPD’s file on Newton’s murder, there was “a bunch of correspondence” between Berndt and Milwaukee police about a possible connection, but the two agencies had no way of placing Dahmer in L.A.

Dahmer had even denied killing Newton before he was murdered in prison in 1994, and Lamberti was unable to find anything new to link him to L.A.

By last November, Lamberti was “at the end of my rope,” he said, and put Newton’s case file back on the shelf.

Two weeks later, Williams contacted Lamberti with a full background he’d worked up for Madden, plus additional background about skinheads operating in the area at the time.

Lamberti and his partner, Det. Tamara Momayez, began digging into Madden. They discovered that the gay porn production company Madden had worked for was in a building on Santa Monica Boulevard that backed onto the alley where Newton’s head and feet had been found.

There was also Madden’s alleged confession to killing in L.A. that Williams had found in McConnell’s book.

“That kind of piqued my interest,” Lamberti said. “Now we were like..., ‘I guess we’re going to Oklahoma.’”

On Jan. 4, Lamberti and Momayez sat down with Madden, who now identifies as a transgender woman and an Orthodox Jew named Daralyn.

“We’re talking to a person who has swastikas tattooed and is also wearing a knitted pink yarmulke,” Lamberti said. “The person we’re talking to is a gay porn actor, transgender skinhead, Nazi orthodox Jew. You write that down in a sentence, and it’s like, ‘What?’”

They started out asking Madden about her life in L.A.

Lamberti said Madden described living “a triple life,” acting in porn as “Billy,” earning cash as a sex worker named “Lyn,” and running around “robbing and pillaging people who were gay” as a skinhead named “Richie Rich.”

Eventually, the detectives eased into the subject of Newton’s murder, and Madden came clean, Lamberti said — confessing in a recorded interview to abducting him from Santa Monica Boulevard at dusk.

According to Lamberti, Madden told the detectives she and her skinhead friends had seen Newton walking along the street and “basically targeted him for robbery.”

Madden said she approached Newton “and kind of put [her] arm around his shoulder,” then calmly told him that they were going to rob him and “probably beat the crap out of” him, and that he was going to go with them without making a scene, Lamberti said.

Lamberti said Madden told them she couldn’t remember where they had taken Newton, but that she had ended up strangling him, which matched the coroner’s findings.

Madden said she believed Newton was high at the time, which also matched the coroner’s findings that Newton had methamphetamine in his system. The timing and location of the attack Madden described also matched other witness statements about Newton leaving Rage, Lamberti said.

Lamberti said it was enough to convince him and Momayez that Madden was indeed the killer, and they presented a criminal case against Madden to prosecutors in L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón’s office.

Lamberti said Gascón’s office has since decided not to file charges against Madden, citing a lack of evidence beyond the confession. He said prosecutors also pointed to the difficulty of proving Madden’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt after 30 years and with so many unanswered questions remaining in the case. A spokeswoman for Gascón’s office said Monday she could not immediately comment on the case.

Nonetheless, the LAPD’s Robbery-Homicide Division is officially closing its investigation in consultation with Newton’s family, Lamberti said.

“We have enough to say that this is the [suspect] who did it,” he said.

Madden could not immediately be reached for comment. An attorney who previously represented Madden in Oklahoma said she no longer represents Madden and was unaware of the confession.

Oliver said her family is pleased with the work of the detectives and sleuths — “Having some kind of closure helps,” she said — and has accepted that prosecutors won’t be pursuing a criminal case against Madden, given she is already set to die in an Oklahoma prison.

“We understand that Los Angeles probably doesn’t want to put this to trial, and there’s no need for it.”

True crime comedy podcast hosts agree across the board that laughing can help quell the shock of a gruesome case.

Still, many questions remain unanswered, she and others said.

“Where is the rest of my brother?” Oliver said, noting most of his body was never recovered. “Why did he have to die? He wasn’t the type of person to piss anybody off.”

Lamberti said Madden told the detectives that, after strangling Newton, she had left his body with her two friends. She was adamant that she did not help dismember him.

She said she knew the identities of her accomplices, Lamberti said, but wouldn’t name them.

“I may be a murderer,” Lamberti said she told them, “but I’m not a snitch.”

Honoring Newton’s story

When Rice and Quinn first decided to talk about Newton’s murder on their podcast, they just wanted to make sure it wasn’t lost to history.

“Let’s get people as obsessed with this story as we are, so it doesn’t go away,” Rice remembers thinking.

When Lamberti called to tell them Madden had confessed, it was “beyond our wildest dreams,” Quinn said.

“I cried. I broke down in tears,” Rice said.

The two plan to celebrate Lamberti’s news on their podcast with champagne and confetti, then keep working on identifying Madden’s accomplices.

Rabins and Williams are right there with them.

Rabins wants to talk to Madden, convinced he might be able to get her to reveal more information to him, including about her alleged accomplices. He also clings to the last time he saw Newton.

“Our last words to each other were, ‘I love you,’” said Rabins, now 68. “I held on to that for so many years. Still do, I guess.”

Williams is already doing a deep dive into the history of white supremacists and skinheads in L.A. in the early 1990s to find out who they were and if they had other victims. Mason is working on a limited documentary series about the case.

The hate that was so clearly involved in Newton’s murder gnaws at him, Williams said.

“Young gay guys like Billy flocked to West Hollywood because they were looking for safety in Boystown. It was that ability to be able to walk the streets without the threat of being victimized,” Williams said.

“The fact that that’s what ultimately ended his life? It’s just infuriating to me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.