Tom Girardi faced more than 150 complaints before State Bar took action, records show

The State Bar of California received 205 complaints against Los Angeles legal legend Tom Girardi alleging he misappropriated settlement money, abandoned clients and committed other serious ethical violations over the course of his four-decade career, the agency disclosed Thursday in response to a lawsuit brought by The Times.

Despite the drumbeat of concerns that began in 1982, the State Bar took no public action against Girardi until after his Wilshire Boulevard firm collapsed two years ago.

As his stature as a trial attorney and political powerbroker grew, officials closed scores of complaints against him without doing any investigation and rejected dozens of others for “insufficient evidence,” the records show. In 13 cases where the agency did act against Girardi, it used “non-public measures,” such as a warning letter, that left his law license and reputation in the legal community unblemished.

Girardi was suspended from the practice of law in March 2021 and finally disbarred by the state Supreme Court in July. Now 83, he has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and is in a court-ordered conservatorship.

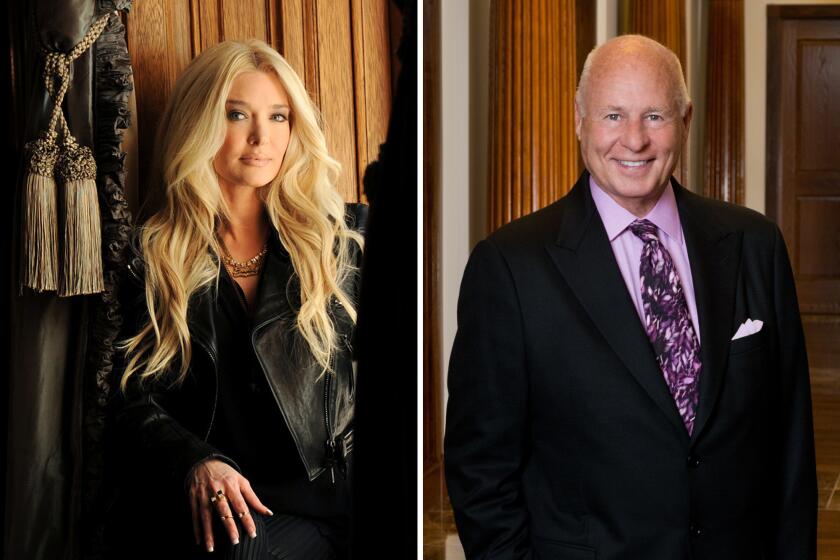

Times reporting has played a starring role in ‘The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills’ this season. Here’s our guide to Erika Jayne and Tom Girardi.

In a letter accompanying the record release, the chair of the Bar’s governing board, Ruben Duran, acknowledged “serious failures” by the agency and wrote: “There is no excuse being offered here; Girardi caused irreparable harm to hundreds of his clients, and the State Bar could have done more to protect the public. We can never allow something like this to happen again.”

Complaints to the State Bar are confidential under the law, but The Times petitioned the state Supreme Court for access to agency records about Girardi under an exception that allows disclosure of information if doing so is “warranted for protection of the public.”

Reporting by The Times has shown how the politically powerful Girardi cultivated State Bar officials, including executives, investigators, prosecutors and judges, with free legal representation, boozy lunches, private plane rides and invitations to glitzy parties.

The agency initially fought the newspaper’s access to Girardi’s records in court but announced last month that it had reversed course after concluding that disclosing the records was “more consistent with its current understanding of its public protection mission and policy of transparency.”

The records released by the State Bar describe the date of each of the 205 complaints, the general violation alleged and its disposition. The alleged violations range from misrepresentations to the court to failure to provide clients with accountings to commission of unspecified crimes.

Of the total complaints, some 155 arrived before the bar took action against Girardi’s law license in March 2021. After the headline-grabbing development, an additional 50 complaints flowed into the agency. Although Girardi became a lawyer in 1965, the earliest available complaints dated to 1982; a Bar spokesperson said the agency has “no available records to determine whether or not there were complaints that predated this.”

Girardi stole at least $14 million from clients in the last decade of his practice, according to a bankruptcy trustee, and nearly 60% of the complaints filed concerned his handling of money in bank accounts meant to safeguard client funds, according to a State Bar tally.

Tom Girardi gave more than $2 million to Democratic politicians during a period in which he was stealing money from clients.

The allegations about missing funds date to the early 1980s and are consistent with allegations that Girardi had a long-running practice of using settlement funds for his own purposes. An Illinois federal judge this week wrote in a ruling that Girardi “was running a Ponzi scheme with client money.”

One complaint disclosed concerned Christian Keith, a teenager who suffered catastrophic brain injuries in a car accident on Pacific Coast Highway in 1985. Representing Keith, Girardi won a settlement of more than $2 million. Records reviewed by The Times show the lawyer promised the young man’s family he would use settlement money to purchase an annuity but never did, resulting in a huge tax bill, and lingering questions about where the funds had gone.

“Mr. Girardi took possession of $2,015,000 and used it as he saw fit, paying himself $500,000 …without court approval,” the family’s new attorney wrote to a State Bar investigator in 1995.

The records show the agency closed the case four years later with unspecified “non-public resolution,” which the State Bar said could mean a private agreement in lieu of discipline, a private admonition or a letter of warning.

Keith’s mother, Sharon, said in an interview Thursday that the family never would have hired Girardi had they known about the conduct reported to the State Bar. She said that given his handling of the money in her son’s case, he deserved to be publicly sanctioned, not punished behind closed doors.

“If there is someone that is a licensed attorney … and especially has a big name … that should not be kept secret,” Keith said. “Other people then fall into the same trap.”

She said that she knew that there were “bad guy” lawyers out there, but Girardi “wasn’t one of them and it didn’t cross our minds.” Christian Keith, now 57, lives in a San Diego County facility for people with brain injuries.

Though the Keith complaint was identifiable in the State Bar’s records release since it referenced the case number and caption of a malpractice suit against Girardi, the identities of others lodging complaints were not discernible.

The State Bar can conduct depositions of the two former employees as part of its internal investigation into whether insiders helped Girardi sidestep discipline and keep an unblemished law license while he misappropriated money from his clients.

Kelli Sager, an attorney for The Times, said the newspaper would press for additional information from the State Bar because the records released “noticeably fail to include any specifics — including the identities of the individuals at the State Bar who were responsible for handling them — or details about the complaints themselves.”

“This information must be disclosed for the public to evaluate its performance and the steps needed to ensure that this kind of ‘serious failure’ does not happen again,” Sager said in a statement.

Duran, in his letter, said the State Bar had disclosed “as much information ... as we believe is allowed under the law.”

The State Bar’s protracted failure to rein in Girardi allowed him to expand his national reputation as a courtroom champion for the little guy, sign up thousands of new clients each year, and become a force in politics and eventually pop culture. A major Democratic Party donor, he socialized with politicians and judges and was regarded as a gatekeeper for would-be judges across Southern California. One of his greatest courtroom victories became the inspiration for the Oscar-winning film “Erin Brockovich,” and he married an aspiring actress, Erika Jayne, appearing alongside her on the reality series “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills.”

The cozy relationships have drawn concern over whether his influence allowed him to elude discipline for cheating clients and colleagues. Earlier this year, the State Bar revealed that it was conducting an investigation by an outside law firm into whether former employees helped Girardi evade discipline. That inquiry is ongoing.

For decades politicians were happy to take Tom Girardi’s money and put up with his requests for something in return. Along with his family and employees, Girardi contributed more than $7.3 million to candidates.

Girardi’s downfall came after a Chicago law firm, Edelson PC, working with him to represent airline crash victims, alerted a federal judge there to millions in missing settlement money. Jay Edelson, the firm’s founder, called the State Bar’s revelations “stunning.”

“What we know now — for the first time — is that the Bar was receiving a constant drumbeat of complaints that Tom and his firm were stealing money for nearly 40 years,” Edelson said. “The Bar spent that time not protecting the public as it was established to do, but shielding the Girardi Keese firm.”

The Girardi scandal prompted a state audit that found widespread problems with the agency’s policing of attorneys, not merely with one prominent trial lawyer. Released in April, the audit faulted the State Bar for ineffective investigations, a reliance on confidential warning letters and other nonpublic discipline, and a poor track record on preventing conflicts of interest between its staff and the lawyers it is supposed to regulate.

That audit and the outrage of the Girardi scandal has led to changes in how the State Bar oversees client trust accounts, the bank accounts where lawyers hold their clients’ money. In a program that takes effect next year, lawyers will be required for the first time to report basic information about all of their trust accounts on an annual basis. Lawyers will also have to distribute client money within specific timeframes, provided there is no dispute over the funds.

The Bar also hired a new chief trial counsel — and former federal prosecutor — George Cardona. He was the first top prosecutor at the agency in a decade to be confirmed by the state Senate.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.