Former State Bar employees must answer questions about Tom Girardi, judge rules

A Los Angeles judge has ordered two former employees of the State Bar of California to answer questions under oath about Tom Girardi and his close ties to the agency that is supposed to protect the public from corrupt lawyers.

The State Bar can conduct depositions of the two former employees as part of its internal investigation into whether insiders helped Girardi sidestep discipline and keep an unblemished law license while he misappropriated money from his clients for years, L.A. Superior Court Judge Michael L. Stern ruled during a brief hearing Wednesday.

“These are valid requests,” Stern said of the State Bar’s efforts to question the two employees. “The depositions will go forward in the month of December.”

After the hearing, the State Bar’s general counsel, Ellin Davtyan, said in a statement that the agency was “pleased with Judge Stern’s ruling, which confirmed our position and paves the way to interview two key witnesses” in the inquiry over the mishandling of complaints against Girardi.

The State Bar’s investigation is one of several ongoing inquiries into the Girardi scandal. A wide-ranging federal criminal investigation is also underway. Girardi’s former chief financial officer was charged this month with wire fraud, which prosecutors describe as a “side fraud” in a wider $100-million embezzlement involving others close to the Girardi Keese law firm.

Girardi, 83, has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and is in a court-supervised conservatorship.

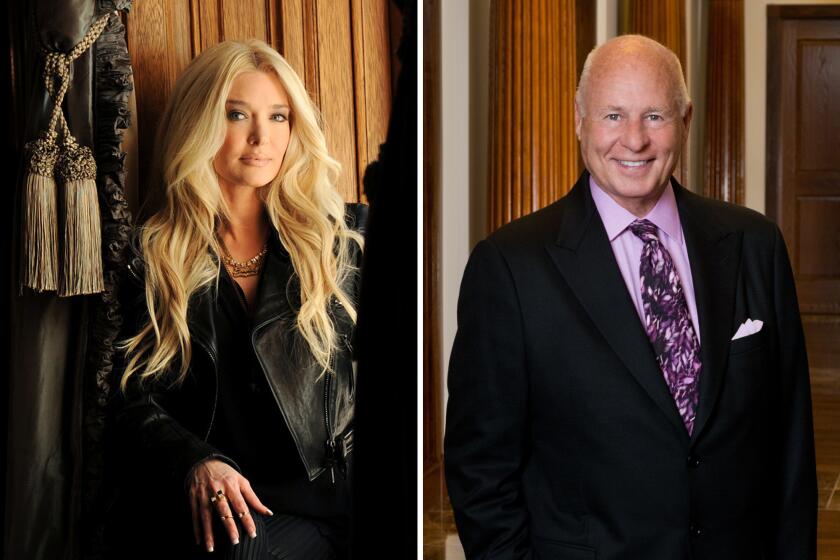

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

The State Bar has not identified the two former employees it is seeking to question, but its attorneys confirmed in court filings that they are Tom Layton, a former L.A. County sheriff’s deputy who later became a prominent investigator at the State Bar; and Sonja Oehler, the onetime executive assistant to Joe Dunn, the former chief executive of the State Bar who was fired in 2014.

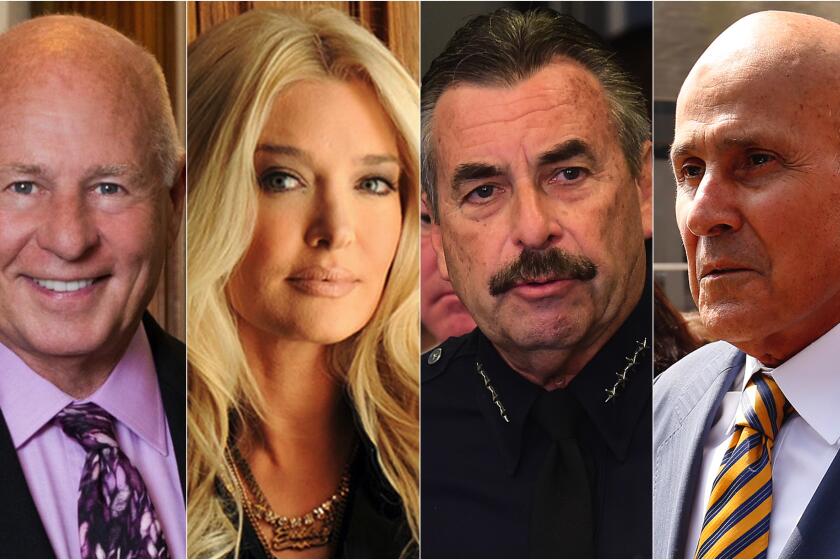

Layton had a close friendship with Girardi during the years when the lawyer was the subject of scores of ethics complaints. He accepted free legal work, travel and meals from Girardi, and one of his children worked at the lawyer’s Wilshire Boulevard firm, The Times has previously reported.

Girardi and the investigator were frequently seen together at Girardi’s law office, political fundraisers, civic events, the Jonathan Club and upscale steakhouses such as Morton’s and the Palm. Layton also had close ties with federal and local law enforcement and cultivated relationships with judges across California. Many viewed him as a surrogate to Girardi.

While working as a watchdog for the public, Tom Layton spent hours advancing the interests and political connections of one lawyer with a long record of misconduct complaints, emails obtained by The Times show.

Oehler and Layton were terminated shortly after Dunn. Both filed lawsuits against the State Bar, eventually reaching settlements in 2019. Oehler received $150,000, while Layton was paid $400,000.

Those settlement agreements have become central in Layton and Oehler’s efforts to avoid providing information to the State Bar about Girardi.

Last summer, the State Bar issued subpoenas to both Layton and Oehler, but both flouted the requests — pointing to the terms of the settlement agreements.

A Times investigation draws on newly revealed records about Tom Girardi’s legal practice, opening a window onto the secretive world of private judges.

The pair share a legal team. One of their lawyers, Derrick Lowe, argued Wednesday that the agreements “forever” blocked “the State Bar from imposing any claims, demands or obligations … including the deposition obligations at issue today.”

Robert Baker, a veteran litigator who is also representing Layton and Oehler, suggested in court that the State Bar was abusing its authority by going after two former employees.

“They are saying that we have this power of subpoena and …. we’re just going to ignore the contract that we entered into,” Baker said, later adding: “This whole thing is a sham to try to produce evidence so they can besmirch and degrade former employees of the State Bar.”

But a top lawyer for the State Bar, Brady Dewar, countered that the settlement agreements had nothing to do with the subpoena to answer questions about Girardi.

The FBI field office in Los Angeles is leading the investigation into Tom Girardi’s former law firm. Its top official won’t talk about his and his mother’s relationship with the disgraced lawyer.

“The obligation to answer questions arose in 2022, and it’s not limited by this release agreement,” Dewar said. He noted that the State Bar had already questioned 15 other witnesses in the internal investigation, none of whom raised objections.

It is unclear how much information the agency will glean out of the depositions.

Baker at one point suggested that the State Bar could only ask his clients about a narrow window of time — 2019, the year they settled their lawsuits, and after.

Aaron May, the outside counsel who is leading the State Bar’s investigation into Girardi, countered, “We absolutely plan to inquire about matters prior to 2019.”

In a Maryland courtroom, the man who once held the purse strings at the famous lawyer’s corruption-plagued law firm stands accused of a federal crime.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.