The settlement Tom Girardi reached with a drug company in 2005 was characteristically large and righteous: some $66 million the famed Los Angeles trial attorney won on behalf of patients who said a diabetes medication caused liver failure and other maladies.

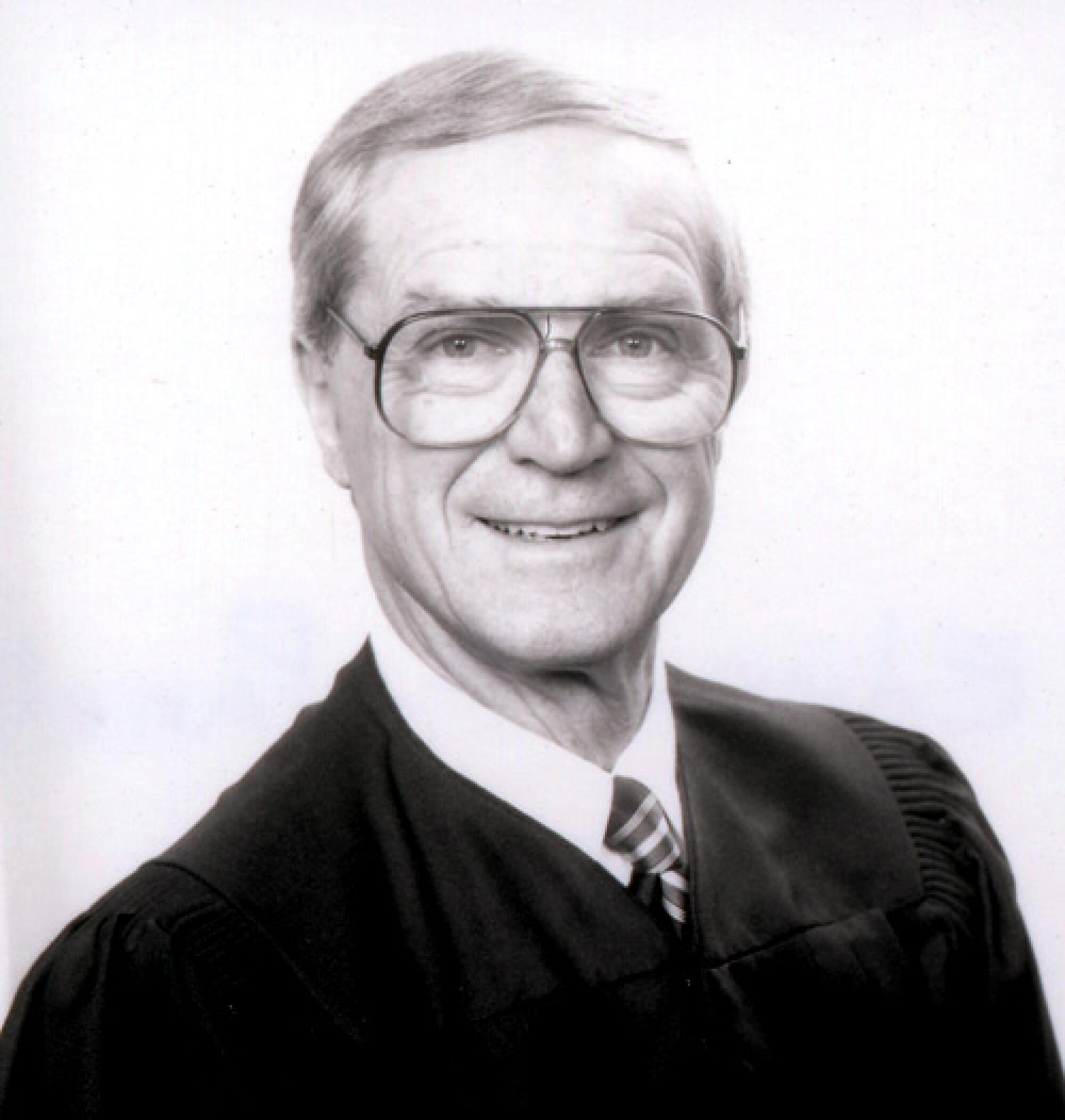

At Girardi’s suggestion, a nationally renowned mediator was appointed to ensure proper distribution of the funds. For overseeing the settlement, retired California appellate Justice John K. Trotter Jr. and his private judging firm, JAMS (formerly known as Judicial Arbitration and Mediation Services), received a $500,000 cut.

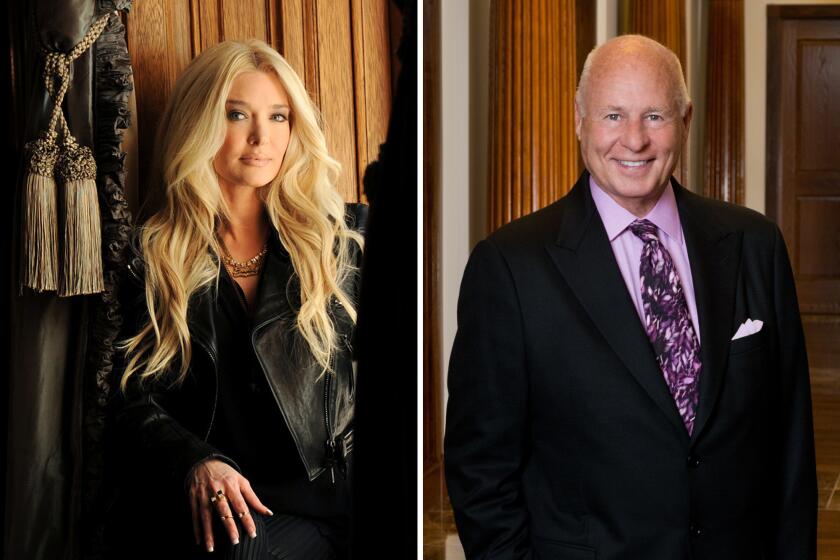

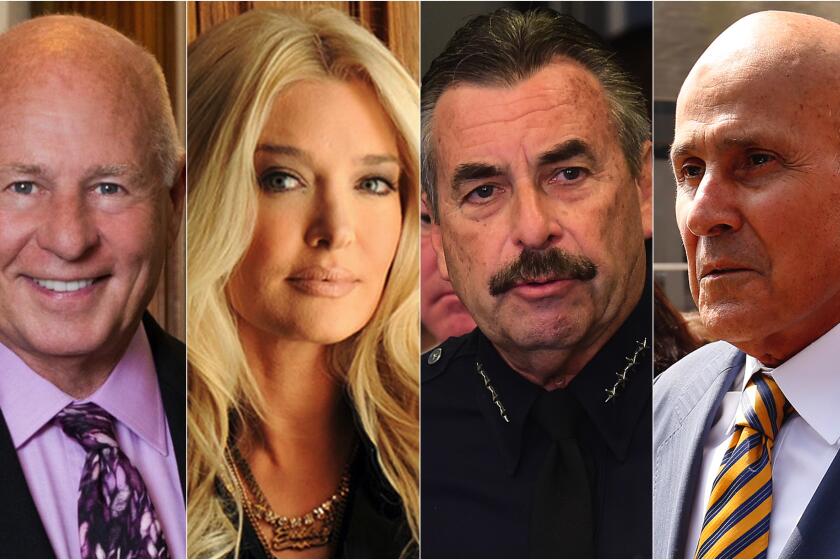

Yet in the years that followed, Girardi diverted money Trotter was hired to safeguard for purposes that were highly questionable and even, in the recent assessment of one federal judge, “a crime.” Girardi sent $750,000 to a jeweler for what Bankruptcy Court records show was the purchase of an enormous pair of diamond earrings for his wife, “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” star Erika Girardi. He dipped into the settlement account again and again for supposed case expenses, sometimes writing multiple seven-figure checks to his law firm in the same week, according to the records.

Ultimately, he took more than $15 million — about 22% of the settlement — for what he described as “costs,” according to a check registry filed in court. Legal experts told The Times the pattern of withdrawals indicated fraud.

Girardi’s firm collapsed a year and a half ago amid evidence that one of the most respected lawyers in California had stolen from clients for decades — the largest legal scandal in state history.

A Times investigation drawing on newly released internal firm records found that his unethical practice depended on private judges, who occupy a secretive corner of the legal world. Girardi’s reliance on them raises questions about whether there are enough safeguards in this highly confidential and largely unregulated industry to protect the public from predatory attorneys.

Retired judges, including Trotter, played prominent roles in administering large settlements from which Girardi is accused of stealing money. Several worked for Irvine-based JAMS, the world’s largest private mediation and arbitration company.

Girardi paid private judges at JAMS and elsewhere up to $1,500 an hour to work on mass tort settlements that often involved hundreds or thousands of clients and tens of millions of dollars, according to court records. When pressed about missing funds, he often invoked the jurists’ impressive credentials. The willingness of the former judges to stand by Girardi in court — and sometimes join him at his lavish junkets and boozy parties — enhanced his aura of invincibility.

In some instances examined by The Times, it is not clear that the retired judges knew Girardi was using them as a shield to fend off scrutiny, such as a 2018 letter in which he blamed delays in paying clients on Trotter’s heart problems. But in others, there is evidence the retired judges were aware of misconduct allegations and assisted him anyway.

In 2001, a former judge helped Girardi improperly siphon $3.5 million from a settlement for workers of Lockheed Corp. (which later became Lockheed Martin Corp.) by signing a sham “order” to release the money to him, according to a copy of the document and correspondence from a bank executive filed in court.

Times reporting has played a starring role in ‘The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills’ this season. Here’s our guide to Erika Jayne and Tom Girardi.

In 2014, a retired state Supreme Court justice then at JAMS was drawn into an attempt to mislead cancer survivors about more than $1 million missing from their settlement. Girardi’s firm, Girardi Keese, told clients that the former justice had instructed the firm to “hold back” the money. The claim was false, but the jurist did not inform the clients or the trial court and fought a subpoena for months before finally being forced to testify under oath. Only then did he disclose that Girardi was lying.

Despite the wide power of private judges in the legal system, no government agency specifically monitors or polices their conduct. Retired jurists often agree to abide by provisions of the Code of Judicial Ethics when working as a referee, special master or similar position, but they do not fall under the purview of the Commission on Judicial Performance, the state agency that investigates the conduct of active judges, an agency attorney said.

“His [legal] skills were phenomenal. The bad part was he didn’t do the money right.”

— Danny Barnes, a Girardi client who started working at Lockheed as a teenager and developed cancer at 27

Some of the retired jurists who worked with Girardi have died. None still living who were approached by The Times agreed to be interviewed. Trotter, 88, has continued to wield influence. Until recently, he was the sole trustee overseeing the $13.5-billion trust for tens of thousands of victims of wildfires in Paradise and other Northern California communities.

“I believe I performed my assigned tasks in an appropriate and timely manner,” Trotter said in a written response to questions about his relationship with Girardi. In a second statement, he added that he did “not know when, how or why [Girardi] morphed from an apparent capable, ethical lawyer to what he is today.”

“The problem isn’t mass torts or private judging, it is Mr. Girardi,” he wrote.

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

Girardi is not in a position to provide answers. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease last year and is in a court-ordered conservatorship overseen by his younger brother. His court-appointed lawyer, Rudy Cosio, declined to comment.

Once cosseted in a sprawling Pasadena mansion, the 83-year-old Girardi now resides in a Burbank nursing home, dependent on family for financial support. In a court filing, his brother, Robert, wrote that Girardi takes medication for dementia and that his “care needs are such that he needs to be at a skilled nursing facility.”

The state Supreme Court stripped Girardi of his law license in June, and he and his firm are the subject of ongoing bankruptcy proceedings.

The Lockheed litigation cemented Girardi’s reputation as an attorney willing to take on big corporations.

Beginning in the early 1990s, he represented hundreds of Lockheed employees who claimed they had been poisoned at the aerospace giant’s Burbank plant. The litigation was complex, with clusters of workers suing Lockheed and a host of chemical companies over a decade. Records from the litigation show that Girardi wrested more than $128 million from the companies.

“His [legal] skills were phenomenal,” said Danny Barnes, a Girardi client who started working at Lockheed as a teenager and developed cancer at 27. “The bad part was he didn’t do the money right.”

Though the law firm was called Girardi Keese, it was owned and controlled by Girardi alone. He brought on retired judges affiliated with JAMS, with the assignment of fairly allocating the money among Lockheed workers. To avoid perceived ethical conflicts, it is common for plaintiffs’ lawyers to hire outsiders to decide how much of a lump settlement each client should receive.

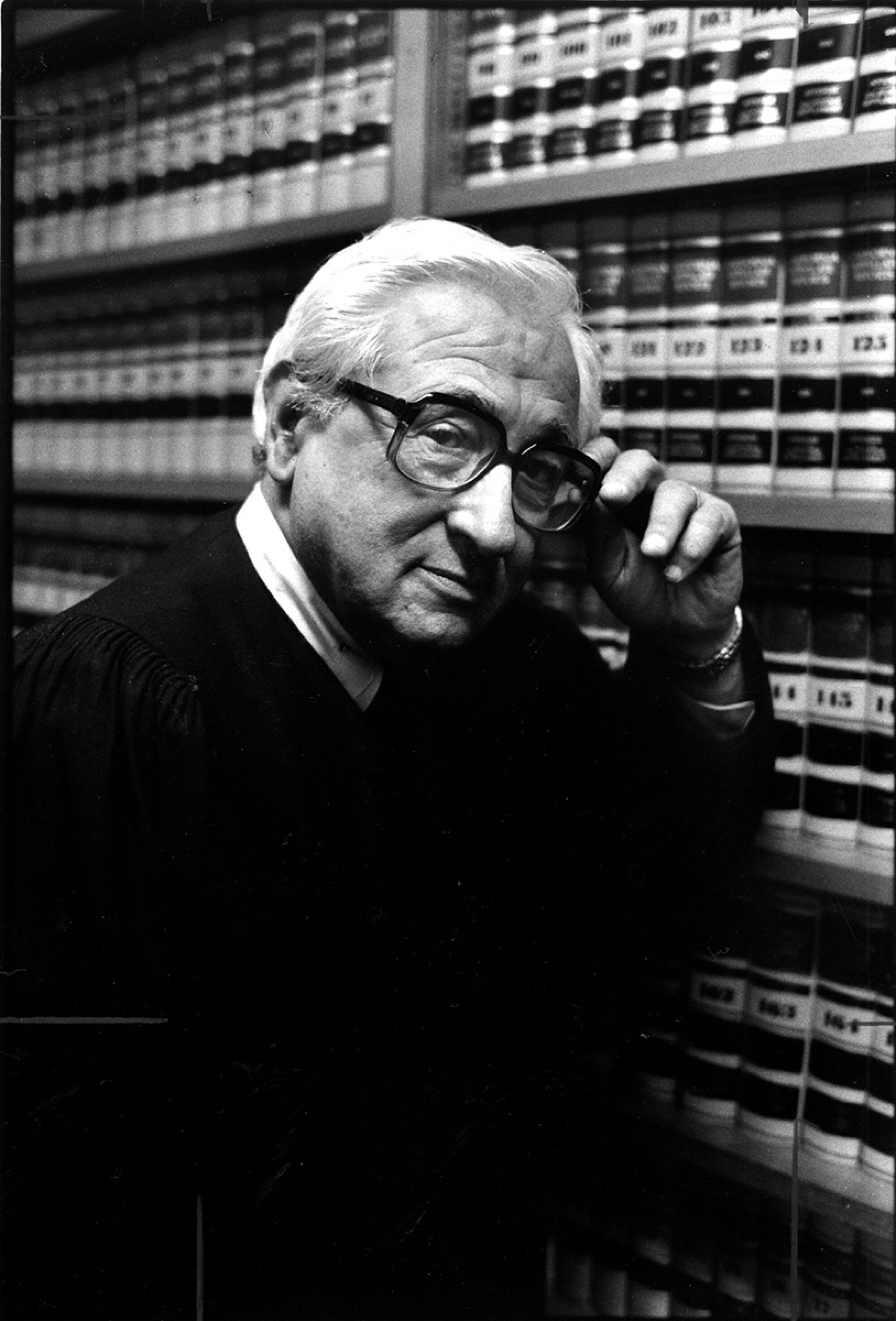

One retired judge working on Lockheed was the late Jack Tenner, who had spent 10 years on the L.A. Superior Court bench and was widely admired for his civil rights activism. Tenner, who was white, worked to integrate firehouses and end discriminatory real estate practices. When Black friends, including future L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley and baseball legend Frank Robinson, wanted to buy homes in white neighborhoods with racist deed covenants, Tenner posed as the buyer and transferred ownership once the sale went through.

For decades politicians were happy to take Tom Girardi’s money and put up with his requests for something in return. Along with his family and employees, Girardi contributed more than $7.3 million to candidates.

He was close to Girardi, officiating at his second marriage in 1993, and was one of three JAMS judges, including Trotter, who helped arbitrate Girardi’s most famous case: the $333-million settlement he won in 1996 for residents of the Mojave Desert town of Hinkley. That case inspired the film “Erin Brockovich.”

After the legal victory, which delivered at least $120 million to lawyers involved, Girardi and a colleague organized a celebratory Mediterranean cruise and invited Tenner, Trotter and other current and former judges. As The Times then reported, most of the jurists eventually repaid Girardi, but questions about the propriety of the trip lingered.

By the time of the cruise, Tenner had worked with Girardi on the Lockheed cases for about five years, and clients and fellow attorneys were growing upset at the lack of transparency and the pace of payouts, according to court records and interviews.

As with many cases Girardi handled, his Lockheed clients were of modest means and education, and as time went on, many were terminally ill from cancer.

“People were one foot in the grave and one foot out and trying to get something,” recalled Mildred Davis, whose husband, Willie, was diagnosed with cancer after a career at Lockheed. She suspected that Girardi saw his clients as easy marks who, in their desperation, would accept far less than they were owed. Girardi, she said, would reason, “If I give them $50,000 or $25,000, they are going to be OK, because they never had that kind of money.”

“It upset my husband that [Girardi] felt that he was so dumb, stupid, that he would just be quiet and sit down,” she recalled. Her husband collected some money but not all he believed he was due, she said. He died in 2014.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Tenner remained firmly in Girardi’s corner. In 1998, after some clients filed complaints with the State Bar and others considered lawsuits, the retired judge sent a letter to Lockheed workers in which he wrote that he and another JAMS judge “want to compliment the law firm of Girardi and Keese for its undying efforts on your behalf.”

The effusive letter did not mollify discontent, and clients continued pressing Girardi to explain what he had done with their money. A partial accounting in 2000, later described in court papers, only deepened their sense of alarm about the settlement and Tenner’s oversight of it.

Millions of dollars had gone to companies and lawyers that had no clear ties to the case and a host of individuals with dubious-sounding names such as K. Ernest Citizen, Giovanni Medici and Lee Marvin, according to court filings. One line item showed $450,000 withdrawn for an “expert witness” fee. It bore the cryptic notation “Confidential (Subject Matter attested to by Judge Tenner).” When pressed for documentation, Girardi refused to provide any.

Tenner died in 2008. The Times did not find any records in which he explained his actions.

The questions about Girardi’s conduct were significant enough that a settlement reached in 2000 with two Lockheed-related chemical companies included constraints on his access to funds. The money was placed in an escrow account, with withdrawals requiring the approval of lawyers for the chemical companies and a mediator.

While working as a watchdog for the public, Tom Layton spent hours advancing the interests and political connections of one lawyer with a long record of misconduct complaints, emails obtained by The Times show.

But in early 2001, Tenner helped Girardi circumvent those safeguards, according to court records outlining the previously unreported episode. Tenner signed an “order to transfer funds” drawn up by Girardi on what appeared to be L.A. Superior Court letterhead; it directed Comerica Bank to release $3.4 million to the lawyer. A bank officer sent the money to Girardi, along with $175,000 in interest. Two days later, Tenner signed a second “order” for an additional $3.6 million, but the bank balked, court filings show.

After the missing funds were discovered six months later, Girardi claimed that he had paid that money to clients, but he would not provide copies of the checks.

“Judge Tenner had no authority to issue any such order, the release of the funds was in direct contravention of the settlement agreements,” Jeffrey McIntyre, an attorney for Girardi’s clients, wrote in a 2002 court filing. He asked a Superior Court judge to bar Girardi from using Tenner “to make any purported ‘Orders’ ” going forward. The outcome of that request is unclear.

Tenner continued supporting Girardi in the face of embezzlement claims. In a 2003 letter to Lockheed clients, Tenner wrote, “You should also know that all settlements to the workers and all legal fees have been approved by me.”

He added, “In my many years as a lawyer, my many years as a judge and my many years as a retired judge, I have never seen the legal effort put forth on behalf of clients like the Girardi firm has done.”

To this day, Lockheed clients say they have never received full payment, and Davis, Barnes and others have filed claims in the pending Girardi bankruptcy case for compensation.

The clients were growing more suspicious by the day.

Girardi in 2011 had reached a settlement of more than $17 million with the manufacturer of a menopause drug called Prempro. Some of his 138 clients, all elderly cancer survivors, came to question his handling of the money and hired a former federal prosecutor who in 2014 demanded an accounting.

Girardi knew the cancer survivors were right; he hadn’t paid them everything they were due, evidence that emerged in court later showed. But instead of fully compensating the women or opening his books to their lawyer, he sent them to retired state Supreme Court Justice Edward A. Panelli.

He had earlier tapped Panelli, a JAMS judge, for what his firm told his clients was the important and difficult work of allocating the settlement. Now he and his firm seized on that role to explain why some cancer survivors had received less than expected. In a letter to the women’s attorney, a Girardi Keese employee revealed for the first time that the firm had withheld 6% of the settlement — about $1 million — and claimed it was at the behest of Panelli.

“I am copying Justice Panelli on this letter and I suggest that we meet with Justice Panelli so that you can verify the 6% ‘hold back’ with him,” wrote James O’Callahan, a lawyer at Girardi’s firm. (O’Callahan died in 2019.)

Though California attorneys are required by law to provide an accounting within 10 days of a client’s request, Girardi refused repeated demands, and the cancer survivors ultimately sued to get the financial records.

In response, Girardi turned again to Panelli. Girardi’s firm filed court papers arguing that the lawsuit should not be decided by the assigned federal judge but transferred to a private arbitration overseen by Panelli. Girardi Keese asserted in a court filing that the retired judge had already been formally “appointed” and “has sole discretion to make awards in the underlying ... ligation.” The filing reiterated the claim that it was Panelli, not Girardi, who had decided to retain $1 million.

A federal judge in L.A. called the argument that Panelli should oversee the case “clever” but rejected it in a decision that colorfully described Girardi’s defense as “the Justice-Panelli-made-me-do-it argument.”

Clients who have accused Tom Girardi of misconduct will be tracking the new season of ‘Real Housewives,’ hoping for evidence to bolster their case.

What the clients and the federal judge didn’t know at the time was that almost everything Girardi Keese said about Panelli was a lie. Evidence that emerged later established that no court had appointed him in the cancer survivors’ case, and he had never instructed Girardi Keese to hold back any money, let alone $1 million.

The claim that Panelli had vast and sole authority over the settlement was also exaggerated. Panelli had spent “approximately 20 hours” on the case, according to a magistrate judge’s analysis. He met with only two or three of the cancer survivors and had merely “rubber-stamped” payouts already decided by Girardi Keese, according to the cancer survivors’ attorney.

“My attendance at any such event never affected my integrity as a lawyer or my impartiality as a jurist or neutral.”

— Judge Edward A. Panelli

At the time, Panelli was working on several cases for Girardi, and the two men had developed a friendship and sometimes socialized. The retired justice seemed unwilling to testify against his friend. He and JAMS fought subpoenas for months, with Panelli arguing in a court declaration that he was too busy to submit to questioning: “With regard to the next eight weeks, with rare exception, I am scheduled to be either engaged in family caretaking obligations, on vacation, or working on previously set matters.”

Finally forced to testify in 2015, Panelli gave up Girardi’s lie.

“Did you authorize Girardi Keese to hold back any portion of the settlement funds from the plaintiffs?” an attorney for the women asked.

“No,” Panelli replied.

By then, the cancer survivors had become suspicious that Panelli was paid excessively for the limited work he had performed. JAMS billed Girardi Keese about $78,000 for Panelli’s time, but records from Girardi’s bank, filed in court, showed another payment: a $50,000 check to Panelli personally. Combined, those payments would amount to an hourly rate of more than $5,000.

Bankruptcy trustees have accused the reality star of concealing assets for her husband and are dispatching investigators to comb through her belongings and accounts.

Asked under oath to explain the personal check, Panelli replied, “I don’t know.”

“Did you ask them why they paid you directly?” a lawyer for the women pressed.

“No,” Panelli answered, according to testimony excerpted in court papers. The full transcript was confidential.

After the deposition, Panelli did not work with Girardi again. Now retired, Panelli, 90, declined to answer questions submitted in writing, including whether he had reported the lawyer to the State Bar or other authorities. But in a statement, he said he had always complied with ethical guidelines established by JAMS and was not swayed by his socializing with Girardi.

“My attendance at any such event never affected my integrity as a lawyer or my impartiality as a jurist or neutral,” Panelli said.

The cancer survivors eventually obtained law firm records that showed Girardi had removed millions of dollars of client money months before he informed the women that the settlement funds had arrived. A forensic accountant who examined the records found evidence of a “Ponzi scheme” in the settlement account, according to court filings. The case settled on confidential terms in 2016.

::

“We finally got him. This time we got the kahuna,” Girardi crowed in 2006 to the audience of his syndicated weekly radio show, “Champions of Justice.” “One of the finest justices the Court of Appeal has ever had.”

The honored guest was Trotter or, as Girardi informed listeners, “a man of great principle,” who, having left the bench, was “the greatest” of the “great men and women at JAMS.”

The praise was so over the top that Trotter, when finally given a chance to speak, joked, “After an introduction like that, I would imagine that you would do very well in front of me the next time you appear.”

“People were one foot in the grave and one foot out and trying to get something.”

— Mildred Davis, whose husband, Willie, was diagnosed with cancer after a career at Lockheed

As it happened, Trotter at the time was handling one of Girardi’s cases: an approximately $66-million settlement with the maker of the diabetes drug Rezulin. The terms were confidential, but Trotter’s role had been spelled out in a 2005 court order appointing him “special referee” for the settlement. Under the order, his duties included “review and approval” of payouts to each of the approximately 4,300 clients, as well as the legal fees due Girardi and his co-counsel and any expenses incurred by those firms in preparing the case.

The L.A. Superior Court judge who signed the order had every reason to trust Trotter. A widely admired Orange County plaintiffs’ attorney in the 1970s, Trotter had served for nearly a decade as a judge, first in Superior Court and later on the state appellate bench. He surprised some in the legal community in 1987 by stepping down to join JAMS, a six-judge mediation firm started by a friend.

In the years that followed, Trotter helped transform JAMS into a national and, eventually, international powerhouse with a pivotal role in the judicial system. The company Trotter built now employs more than 400 arbitrators in 29 locations, and many important legal disputes, particularly those involving corporations, play out not in public courtrooms but behind closed doors at JAMS. (The Times has used JAMS to resolve disputes.) Although he retired from JAMS five years ago, Trotter said he remains a shareholder. A spokesperson for JAMS said he stopped being a shareholder in 2020.

In the Rezulin settlement, the court made Trotter a gatekeeper for the funds. No money was to leave an escrow account at Comerica Bank except “as directed” by the retired justice, according to a court order. Yet almost all of the settlement — some $65 million — poured into a separate law firm account controlled by Girardi, according to internal Girardi Keese records that became public this year in bankruptcy proceedings.

Just over a month after he gained access to the money, Girardi wrote a check on that account for $750,000 to M.M. Jewelers. The family-owned store in downtown L.A. had created several pieces in the $15-million jewelry collection of Erika, his now-estranged wife, and the funds from Rezulin went to purchase a set of diamond stud earrings to replace a pair that had been stolen in 2007 from the couple’s home, according to declarations from Girardi and a store owner that were filed in the bankruptcy proceedings.

“The diamonds were of exquisite quality and very large,” Ared “Mike” Menzilcian recalled in the affidavit.

In a hearing this summer in L.A., the federal judge overseeing the Girardi Keese bankruptcy said the earring purchase “clearly was a crime.”

“This was an embezzlement. This was a theft,” U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Barry Russell said.

Though there is an ongoing federal investigation into Girardi’s misappropriation of client funds, no charges have been filed.

Trotter said in a statement that he was unaware that Girardi transferred settlement money to a jewelry store.

Girardi categorized the purchase in internal firm records as a “cost,” meaning a case expense deducted from the amount that went to clients. Put another way, Girardi was charging his clients for his wife’s earrings. And there were other questionable withdrawals billed as “costs.”

At various points over a 21-month period, Girardi removed money from the account for what he claimed were expenses, according to a check registry filed in Bankruptcy Court. The checks, made out to the firm Girardi solely controlled, were for large sums and, with one exception, were for round numbers such as $4 million, $1 million, $500,000 or $100,000. They eventually totaled $14.3 million.

Experts who reviewed the court order and financial records at the request of The Times said there were numerous red flags.

The Times reporters covering Tom and Erika Girardi explain what “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” revealed — and what they still want to know.

“You are never going to see a round number like $1 million or $750,000, because the costs are never that way. They come with pennies,” said Charles Silver, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law who specializes in civil practice.

He and others said attorneys usually deduct all or almost all of their expenses at the outset and not as Girardi did, with more than a dozen withdrawals spanning about two years.

“It doesn’t make any sense,” said forensic accountant Steve Franklin, who had examined records in the cancer survivors’ litigation. “They are treating it like a slush fund.”

By comparison to the vast sums Girardi took, Trotter approved just $604,500 in cost reimbursements for a Pasadena law firm that partnered with Girardi Keese on the case and did substantial work preparing suits for trial, according to emails filed in Bankruptcy Court.

“How did this go for so long without being discovered?” asked UC Irvine Law School professor Carrie Menkel-Meadow, who has worked as a mediator and written extensively on ethics and mass tort settlements.

She and others said it is incumbent on anyone overseeing a settlement to demand invoices, receipts or other proof that costs are legitimate.

Asked to explain his handling of the Rezulin settlement, Trotter said in a statement that “questions regarding a 17-year-old case are difficult to answer with specificity,” but he “did not in any way authorize nor know about the withdrawals you reference that Mr. Girardi labeled as costs.”

“They appear to be Mr. Girardi’s unlawful use of client funds and had nothing whatsoever to do with actual costs,” Trotter said.

Whatever the oversight failures in Rezulin, the case brought Trotter further acclaim. The National Law Journal cited his work on the settlement in a 2011 article that declared him the country’s “most influential” attorney in alternative dispute resolution.

Trotter and JAMS were also paid handsomely. Their $500,000 fee was not widely known before it was revealed this year in Bankruptcy Court, and its size has raised eyebrows.

During a hearing this summer, an attorney for Erika Girardi, Evan Borges, called the sum “very suspicious,” adding, “I’ve never heard of such a thing.”

JAMS confirmed receiving the fee in the Rezulin case but refused to provide invoices substantiating Trotter’s work and declined to make executives available for interviews. The company did not answer questions submitted in writing but said in a statement that its retired judges “are expected to adhere to the ethical standards that they swore to uphold under oath.”

In 2015, the year Erika debuted her lavish lifestyle to viewers of “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills,” her husband was negotiating settlements that would ultimately total $120 million for residents of a Carson neighborhood who claimed they got cancer and other maladies from polluted soil.

At Girardi’s request, Trotter was appointed as special master to divide the funds secured from an oil company and a real estate developer among about 1,500 clients affected by the pollution at Carousel, a housing development north of the Port of L.A.

Years passed, but the settlements — one announced in 2015, another in 2016 — remained partly unpaid, and clients complained. Chris Gutierrez, a public school teacher who had lived in Carousel since childhood, took to dropping by Girardi Keese’s Wilshire Boulevard offices on his way home from work.

“I would be waiting there for like an hour, and they wouldn’t give me the information,” Gutierrez recalled. “I think they were irked I actually showed up.”

It seemed inconceivable at that time that Girardi could be delaying payment because he was short on cash — one had only to watch his wife on “Housewives” to see the couple’s opulent home and her designer clothes and personal “glam squad.”

Girardi responded to clients’ ire with a series of letters that pinned the blame for delays on Trotter, bankruptcy filings show. In April 2017, he told them, “We have now satisfied all the requests of the Special Master and, beginning next week, we will be issuing checks.”

Months later, the funds still delayed, Girardi wrote again, emphasizing that Trotter, not his firm, was responsible for the holdup: “Every penny of the settlement was governed by him including the timing in which funds could be distributed.”

More than a year later, Girardi floated a new explanation. Trotter, he wrote, had “a terrible heart condition and he has been unable to handle many of the issues.”

A few days later, Girardi related supposed sickbed comments from Trotter.

“I did speak to his wife and asked if we could at least do a partial payment as soon as possible. She discussed the matter with him and told me that he said he gave consent,” Girardi wrote, adding, “Mrs. Trotter thought that his heart condition would settle down and he would be able to have a meeting in about 30 days.”

It is unclear what Trotter’s physical condition was at the time or whether he knew of Girardi’s letters to clients.

Within months, Trotter had a new job with enormous responsibility: serving as the trustee of the multibillion-dollar trust for Northern California wildfire victims. He declined to answer questions about the purported heart condition or other Girardi correspondence but said in a statement that his duties were limited to deciding the amount of a plaintiff’s award.

“I had no authority or oversight and was not in any way involved with the timeliness or distribution of the money. Nor was I privy to Mr. Girardi’s comments,” he said.

On at least two occasions, Girardi sent partial payments to clients, saying Trotter had authorized him to pay out some but not all of their money, according to letters the clients submitted to Bankruptcy Court. Experts consulted by The Times said attorneys can hold back money earmarked for specific medical costs incurred by clients, but state law requires them to pay funds due to clients “promptly.”

“I would be suspicious right away that there was some misappropriation,” said Kevin Mohr, a professor at Western State College of Law who chaired the State Bar’s Committee on Professional Responsibility and Conduct. “Whatever is undisputed, the client has to be paid.”

The partial payments raised questions about how Trotter was apportioning money. Carousel residents said in interviews that the process seemed random, with little correlation between the settlement award and the time a client had lived in the neighborhood or the injuries claimed.

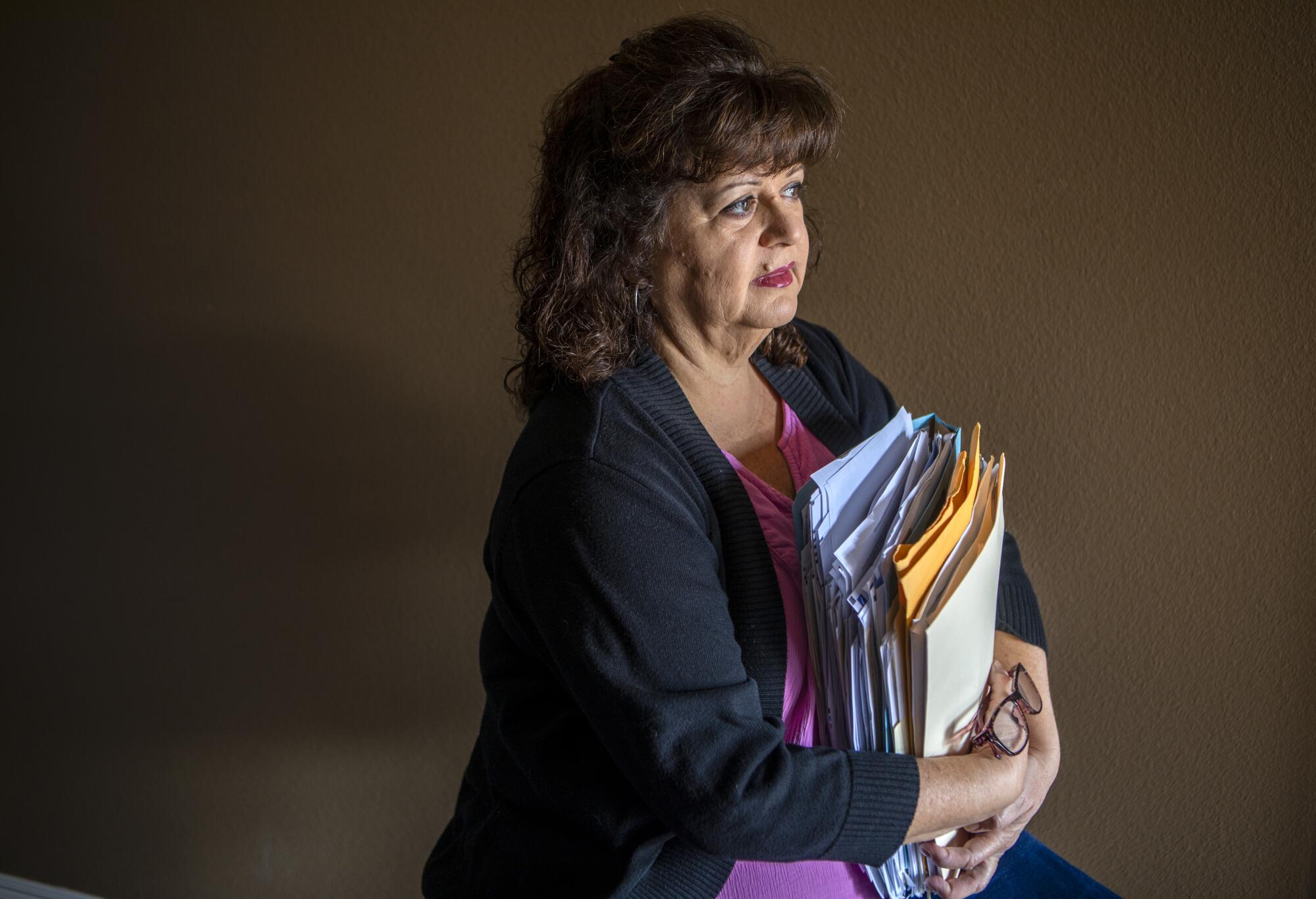

Regina Torrez, a court reporter and cancer survivor who had lived in the neighborhood for decades, said she had hoped Trotter’s involvement would root out fraud and “correctly disburse the award.” But she came away disappointed.

“I don’t think they went through the applications and figured out how people were affected and what injuries they had,” Torrez said.

Some appealed to Trotter, without success.

“They never responded to me,” said John Parago, who wanted to detail for Trotter how he survived testicular cancer as a teenager. He wondered whether “they were just waiting for people to pass so they wouldn’t have to pay us.”

Carousel client Richard Fair sued in 2017 for an accounting. As he had in the past, Girardi tried to move the suit outside of court into private arbitration with a JAMS judge. In court filings, he contended that Trotter had jurisdiction because of his ongoing work in the settlement.

An L.A Superior Court judge rejected the proposal, but Girardi tried again months later, including in his request a copy of a letter to Trotter marked “Personal & Confidential.”

“We would like you to set a date and time for a hearing in this matter,” he wrote to the retired justice. There is no record in the court file of Trotter responding. The request was denied.

“My sense was that he felt Trotter would rule in his favor. I don’t know why else he would want Trotter in there,” said Fair’s attorney, Peter Dion-Kindem.

Girardi repeatedly refused to turn over financial records showing what he had done with the Carousel money and continued to call upon Trotter to fend off the lawsuit. One of the allegations against Girardi was that he had bungled the $120-million settlements by leaving the funds for years in his firm’s trust account, instead of in an interest-bearing account that could earn money for clients.

Trotter vouched for Girardi’s handling of the money, writing in a 2019 declaration that “it would have been totally absurd to try to allocate interest to an individual plaintiff.”

Experts consulted by The Times said the retired judge’s reasoning was flawed. State regulations do allow attorneys to keep “nominal” funds in their firm trust accounts for a short period of time, with the interest going to the State Bar for distribution to nonprofits that promote public access to the courts.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

But “there’s no way that millions of dollars held for any period of time fits within this category. No way,” said Jack Londen, a partner at Morrison Foerster who worked on the litigation that upheld the trust fund statute.

Trotter said in a statement that he stood by his original conclusion, but conceded that at the time, he was “unaware of the allegations regarding Mr. Girardi’s conduct.”

“Had I known, my opinion would not have changed, but I certainly would not have engaged with him in any way,” Trotter said in the statement. He blamed the State Bar for not catching Girardi but refused to say whether he had ever informed the agency of misconduct by the lawyer.

Fair died last year, before his suit went to trial. Scores of Carousel residents have joined hundreds of other Girardi clients in filing bankruptcy claims to try to recover some of the tens of millions of dollars they say are owed to them.

“We don’t have a lot of sway,” said Parago, one of the dozens of residents who submitted a claim. “We’re the small people.”

Last month, the Bankruptcy Court seized Erika Girardi’s diamond earrings and said they would be sold, with the proceeds going toward those cheated by Girardi.

Those who have lined up for repayment include JAMS, which last year submitted a claim for an unpaid bill of $9,660.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.