The memory of L.A.’s seedy gambling boats faded. Here’s how we recovered it

Barnacled and throttled, the underside of the Santa Monica Pier is the shadowed obverse of the cheery tourist destination above it.

I’d come to the pier in search of California history and realized it was that gloomy underside that symbolized what I was interested in, a darkened world of waves and wet timber.

Because this was Tony Cornero’s domain.

The story of Cornero — the gambling boat kingpin who squared off against future U.S. Chief Justice Earl Warren at the Battle of Santa Monica Bay — seems like it should be a well-worn tale in the Southland and beyond. But it’s not.

Maybe it’s because unlawful gambling seems quaint now, when it’s easier than ever to do it legally. Or perhaps it’s because much of the physical evidence of the era has been scuttled — in some cases, literally.

Water-cannon gangsters, booze-soaked vice dens: How 1939’s ‘Battle of Santa Monica Bay’ brought down L.A.’s floating casinos.

Either way, collective memory of the gambling boats of the 1920s and 1930s has faded, making it difficult to get a handle on this louche L.A. moment and the infamous Cornero, the subject of Wednesday’s Column One.

Trying to understand Cornero, the enigmatic owner of the S.S. Rex, I immersed myself in a version of his world. I reread Raymond Chandler’s 1940 novel “Farewell, My Lovely,” which includes a character who is modeled after Cornero, scholars say. I watched the 1943 film “Mr. Lucky,” in which Cary Grant plays the owner of a gambling ship who was also patterned after the businessman.

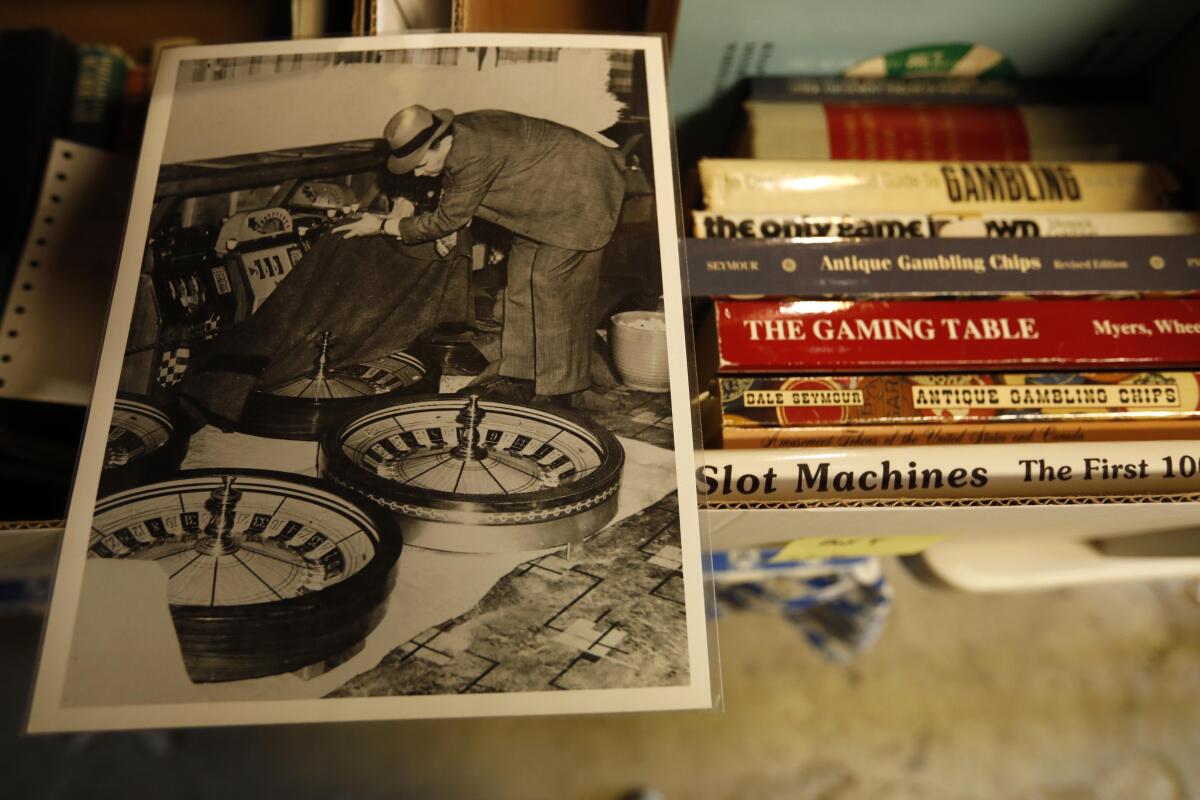

I searched antique stores and marketplaces for artifacts from Cornero’s ship, which anchored a little more than three nautical miles off the coast of Santa Monica — supposedly beyond California’s jurisdiction. Matchbooks, casino chips and dice — I thought it would somehow help if I could hold these things in my hands.

Like a mysterious ocean current, something kept pushing me along. To Santa Monica.

Before long, I was crisscrossing the city, whose coastal waters had accommodated the Rex and other gaming barges until 1939, when the battle put an end to the scene. I wanted to understand how the tony city had contended with Cornero, a cavalier ex-bootlegger who once cheekily claimed that his Prohibition-era rumrunning exploits were actually a public service meant to protect “120,000,000 people from being poisoned to death” by bad hooch. (He went to prison over it.)

Cornero wasn’t the first to open a gambling boat in the Southland — Long Beach saw one debut in the late 1920s — but he knew how to stand out. His 300-foot-long Rex, the most opulent of the barges, promised “all the thrills of Riviera, Biarritz, Monte Carlo and Cannes surpassed” and attracted all manner of Angelenos.

And the water-taxi ride to the Rex began not far from where I was standing on the pier.

::

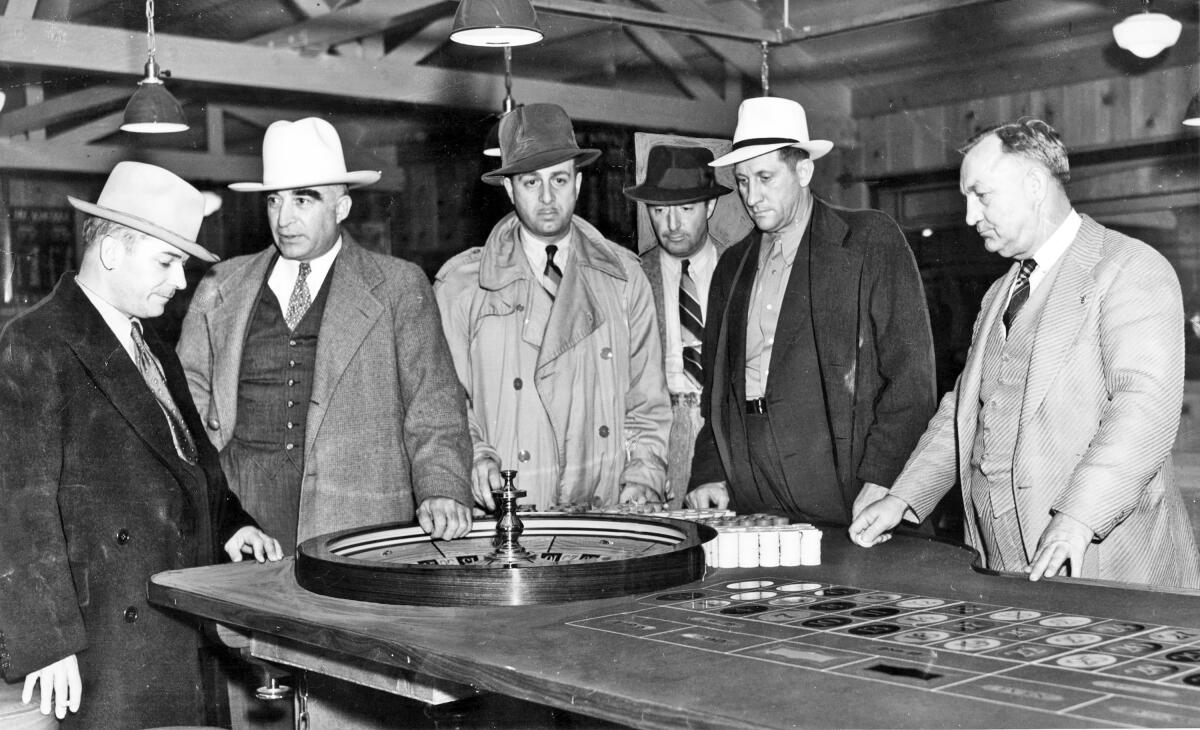

In a little, wood-paneled room above the pier’s carousel, Jim Harris jiggled a pair of red dice in a loose fist and opened it onto his desk. There was no money on the line, but that wasn’t always the case for these cherished artifacts — because they were from the Rex. Clutched by croupiers and criminals, those dice must’ve seen their share of stakes.

The deputy director of Santa Monica Pier Corp., Harris has worked there for 31 years, starting as a bartender at the erstwhile Boathouse restaurant.

Back then, he said, street gangs roamed the pier at night, but behind the bar he was serving crusty regulars a cocktail he had co-created. It was called the South of Malibu — a union of Southern Comfort, Malibu rum and pineapple and cranberry juices that Harris said “was not for lightweights.”

Harris, the unofficial historian of the pier, offered me a tour, beginning with the area where, he said, Cornero had painted a red “X” on the side of a building to show customers where they should line up to buy tickets for water taxis that would spirit them to the Rex. “The ‘X’ was very much a code or a secret handshake for those in the know,” said Harris.

The vessel embodied Cornero’s style and personality. “Calling a ship the Rex — I mean, it’s Latin for ‘king,’” Harris said. “That was the biggest feather in his cap — he was the king of the ocean.”

We walked down to the sea-sprayed platform near where water taxis once picked up patrons and ferried them to the floating casinos.

“A journey out to one of the gambling boats would be risking your life,” Harris said. “The people who were running these operations were certainly of questionable character, and you didn’t want to cross them in the wrong way.”

We made it to the end of the pier. Fishermen cast their lines 30 feet below in search of halibut, perch and mackerel. I squinted at the horizon. A wind lifted off the ocean. From this spot, on a clear day like this one, Harris said, the Rex would’ve been visible.

But I couldn’t envision it. At least not yet.

::

It’s easy to experience bits of L.A.’s history firsthand: You can ride the funicular at Angels Flight or put your hands in the prints at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. But not the gambling vessels — several rest at the bottom of the Pacific, their slot machines and secrets forever out of reach.

Still, you can talk to the people who were there, though only a few are left.

Florence Kinney was one of those who remembered. In pre-pandemic days, I met her at the Santa Monica History Museum, where the centenarian sat in a wheelchair with hands like maps she kept folded in her lap.

Born and raised in Santa Monica, a stone’s throw from the residence of movie stars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, Kinney — who died Jan. 1 at 108 — came of age in the 1920s. She recalled Saturday nights promenading on Third Street and trying to snatch the brass ring at the pier’s merry-go-round to get a free ride.

“Santa Monica was a wonderful town,” she said. “We had no fear of going anyplace.”

Indeed, in the years before the gambling boats’ arrival, Santa Monica had been a quiet tourist destination.

“We were a sleepy town,” said museum archivist Sara Crown, noting that in the late 1910s, there had been a local temperance movement that preceded Prohibition. “It [was] a pretty wholesome place. You know, a family community.”

Then the gambling boats arrived. The closest Kinney ever got to them was the shore, where you could see their lights at night, she said. But her husband, Ray, made a trip with his pals, who knocked back whiskey cocktails while they lost money at the card tables.

“The boat took quite a bit,” said Kinney, laughing.

But Kinney said she never heard anything negative about Cornero or his venture. So she was disappointed when authorities went after the Rex, hitting its operators and those of other gambling vessels with public nuisance charges in a prelude to the raid that became known as the Battle of Santa Monica Bay.

The barge and its ilk had been “a drawing card” for the city, Kinney said.

But her rosy remembrances obscured a truth: There was plenty of trouble. It seemed to follow Cornero wherever he went. And it hastened the demise of the gambling boats.

::

Searching for a piece of tangible history, I’d spent weeks chasing Cornero’s ghost across Santa Monica — mostly in vain. But there supposedly was a treasure hidden amid the rattan and rust of the city’s oldest restaurant that could transport me to that time of swashbuckling gambling impresarios and their gilded pleasure boats.

An out-of-print book, “Shipwrecks of Southern California,” said that after another gaming vessel, the Texas, was sunk following its seizure during the battle, salvors recovered its starboard light and donated it to the Galley on Main Street. “The light is still doing good service by providing illumination for the establishment’s pay phone,” the book said.

Ron Schur, the Galley’s owner since 1989, said over the phone that he didn’t know about the lamp. Still, the man known as “Captain Ron” welcomed a hunt.

On a quiet weeknight, Schur eased me into one of the restaurant’s dim booths, where a tin sign on the wall said “CERTIFIED FOR ACCOMMODATION OF MASTER.” A waitress offered to select my drink, and I obliged. Before long, the glass was empty — with another mai tai on the way — and Schur was telling me about a former regular who worked as a water-taxi operator. Schur doesn’t know Bobby’s surname — and he died years ago — but he remembers the old man telling him that he transported movie stars, including Errol Flynn and Cesar Romero. Mobsters, too.

“These guys appreciated what he did,” said Schur. “They gave him big tips.”

I poked around the restaurant, which opened in 1934. It teems with maritime ephemera: fishing nets, buoys, diving helmets. But the wall above the pay phone was barren.

A ponytailed barman who’d watched me from afar gestured to follow him onto the back patio. He walked up to a row of bushes that lined the rear of the property and plunged his hands in. He pulled out a lamp and set it on a barrel. Its tarnished flanks managed to catch a little light. The metal badge read “Starboard.”

“My God ... a piece of history!” said Schur, who then remembered that he’d taken down the lamp years earlier, when the pay phone stopped working. “I have something that’s part of history. And I didn’t even know about it.”

Schur studied the lamp, and I put my hands on it. The surface was rough, almost mottled, a kind of patina that can be earned only at sea.

Finally, I felt connected, too.

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.