The government boats knifed across the Pacific, cutting a line toward the ship floating a little more than three nautical miles off the California coast.

The S.S. Rex was the biggest and most opulent gambling boat anchored off Santa Monica in 1939. And the man at the helm was a brash bootlegger-turned-gaming kingpin who wore a white Stetson, lived in a Beverly Hills bungalow and held court at the Trocadero nightclub.

His name was Tony Cornero.

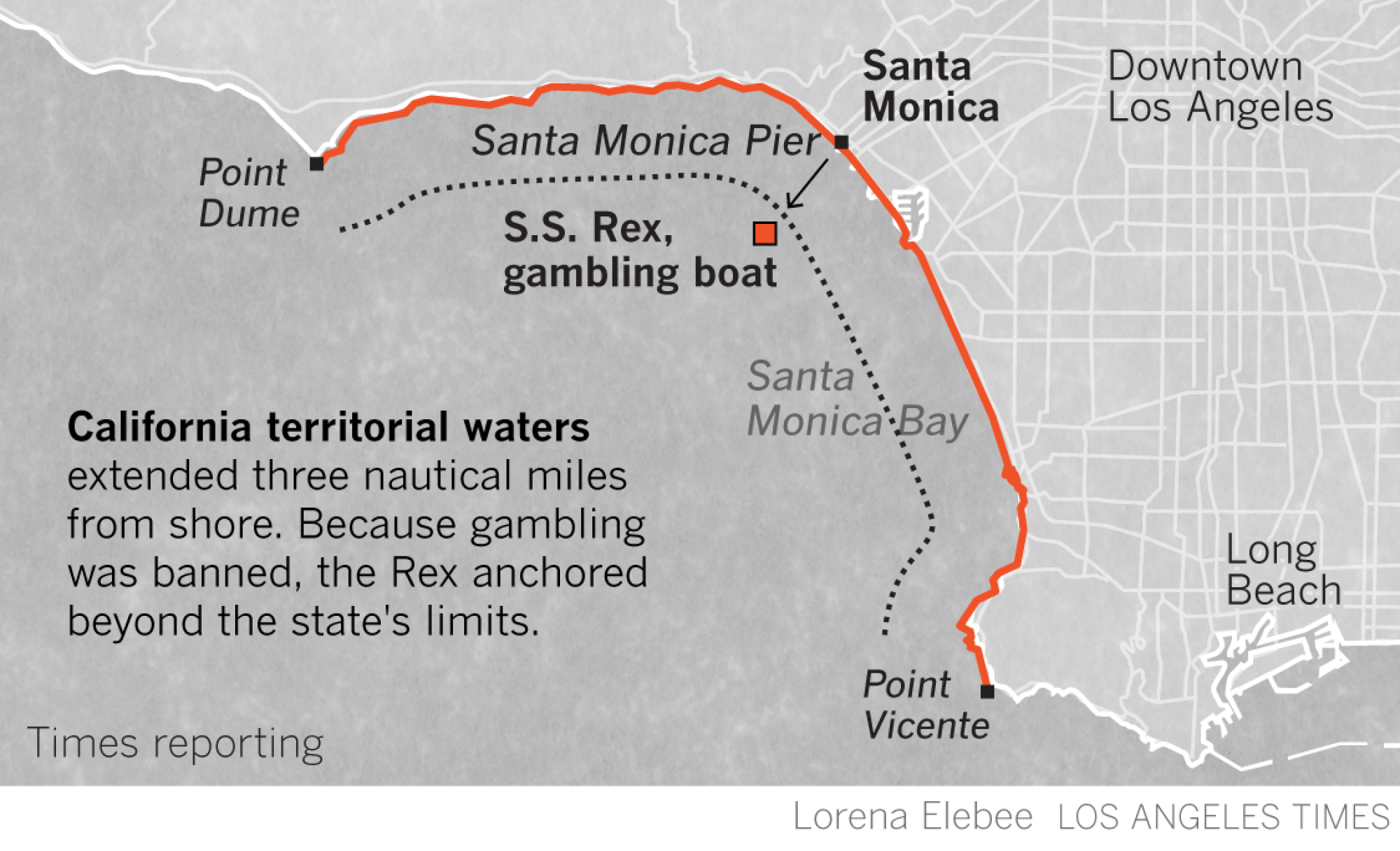

Cornero and others like him saw a way around California laws prohibiting gambling by operating floating casinos in waters they believed to be beyond the state’s jurisdiction. But the authorities disagreed with their interpretation of geography.

On this August day, the Rex had 600 passengers, an assortment of Angelenos enticed by booze-soaked games of blackjack, poker, roulette and more. But 250 law enforcement agents were fast approaching Cornero’s vessel at the direction of California Atty. Gen. Earl Warren, who had labeled the Rex and its peers the state’s “single greatest nuisance.”

Agents raided three other ships, and those operators quickly surrendered. But not Cornero. He had the Rex’s gangway barricaded and set loose powerful water cannons on officers who tried to board.

“Nobody’s coming aboard this ship!” Cornero shouted, according to the Los Angeles Examiner. “We’re on the high seas and we’re prepared to defend our rights. Try to use force, and we’ll use it, too.”

The Battle of Santa Monica Bay was on.

::

They were converted lumber schooners, steamships and minelayers, transformed into vessels with names evoking glamour: Star of Hollywood, S.S. Tango, S.S. Monte Carlo. And the Rex.

In 1939, there was a fierce battle in the waters off Santa Monica over a gambling ship operated by a notorious kingpin.

In Santa Monica, beachcombers could hear the faint, eerie sound of swing music wafting from the ships, but only when there was an onshore wind. A pamphlet for Cornero’s Tango promised “dinner, dancing and entertainment” that lasted “from 6 p.m. to ??”

The gambling boats of the 1920s and ’30s may seem quaint now, given how easy it is to legally gamble in California, and the aquatic raids just a curiosity. But in a roundabout way, what the press called the Battle of Santa Monica Bay helped launch Las Vegas as we know it. And key to it all was the enterprising man few remember, Tony Cornero.

Born Anthony Cornero Stralla in 1900, he spent his earliest years in Italy’s Piedmont region, the son of a hard-luck farmer. After three years of bad corn crops there finally was a bounty, but, as Cornero later told the Saturday Evening Post, his father lost everything in a card game.

“Meantime I was playing out in the fields and accidentally set the harvested corn afire,” Cornero told the Post. “My mother said: ‘There’s nothing left; we’ll all have to go to America.’”

The family migrated to the San Francisco Bay Area. Living in Los Gatos a few years later, Cornero had a childhood epiphany while shooting craps. Like his father, he lost everything.

“I saw that in playing the other fellow’s game, I was only making a squirrel of myself,” Cornero said. “So I decided that the smart caper was to make the other fellow play my game, and that’s what I have been doing ever since.”

By his teenage years, Cornero was dabbling in crime; robbery charges in 1916 — he confessed to leading a gang of “jitney bandits,” the Oakland Tribune reported — led to a stint in reform school.

The advent of Prohibition created an opportunity: People needed their booze, and Cornero provided it. The 1920s saw him arrested multiple times for allegedly violating the National Prohibition Act, the FBI’s 539-page Cornero dossier shows. There was even an arrest on suspicion of murder, but apparently no charges were filed.

Early on, Cornero developed a flair that served him well in his illicit pursuits. When authorities put up a roadblock to keep him from trucking liquor to the Napa River, he devised a workaround, according to Fred Grange, the son of Cornero’s business partner.

“On one side of the roadblock, they shut off the fire main,” said Grange, 77. “On the other side, they shut off another pipe. They just pumped the hooch ... underneath where the G-men were.”

Safely past the roadblock, the bootleggers pumped the booze out of the pipe and back into containers on their vehicles.

“His brain was supercharged,” Grange said.

Eventually, Cornero wound up in prison due to another bootlegging operation, but he was a free man by the start of the 1930s. And a rich one. Cornero made $1 million as the Southland’s “King of Rumrunners,” The Times reported in 1955.

But that was nothing compared with the Rex. Cornero spent $200,000 transforming a 300-foot-long former windjammer into a casino. It boasted 150 slot machines, a 250-foot bar and “ladies in form-fitting dresses to lure customers,” the L.A. Herald Examiner reported years later. It also boasted something sinister on the off-limits top deck: machine guns “set up fore and aft,” according to the Saturday Evening Post. “Three shifts of gunners man them every minute.”

The Rex opened May 5, 1938; Cornero promoted it with skywriting and ads assuring it was “run honestly.”

The ship’s many gaming offerings — and that promotion — added up to an innovation: making gambling appealing to the middle class.

“Gambling was either the purview of the very wealthy or the very poor; it was either in luxury surroundings or in some kind of snake pit,” said historian Alan Balboni, whose book “Beyond The Mafia: Italian Americans and the Development of Las Vegas” covers Cornero. “He did open it to the middle class. For any of his failings, he was a real entrepreneur.”

Soon, the Rex was claiming a daily profit of as much as $12,000 — the modern equivalent of $231,000. By then, Cornero was tied to a constellation of high-profile criminals, among them Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel. Cornero had nicknames of his own: “Tony the Hat” and “Black Tony.” Out on the water, he went by another: “the Admiral.”

Still, if not for the gambling boat plotline in Raymond Chandler’s “Farewell, My Lovely,” which includes a character scholars say is modeled after Cornero, it’s doubtful many Angelenos would have even a foggy sense of this era.

A reporter journeys across Santa Monica in search of a story about a louche moment in the tony city’s history.

Cornero certainly seems lifted from a noir novel, but was the gambler also a gangster?

An answer appeared elusive, because the dead don’t talk, and sometimes the living won’t, either. One of Cornero’s few remaining relatives declined to be interviewed and warned that a writer she’d spoken to years earlier wound up mothballing a project on Cornero under mysterious circumstances.

She implied that organized crime was involved in the silencing.

::

In some accounts, Cornero was ruthless; in others, merely a provocateur.

But further insight into him comes from a surprising source: the unpublished autobiography “From Grunt to Colonel in 33 Years” by Louis J. North. His mother was Cornero’s sister. North completed the manuscript in 2016, two years before he died at 93.

“He taught me how to shoot craps on the living room rug,” North wrote of his uncle. The memoir also revealed a secret.

During Prohibition, Cornero and North’s father, Charles North, started a bootlegging outfit on a small island along Canada’s Pacific coast. “They would buy Canadian booze, load it on their boat, run it across Puget Sound, and offload it on the beach near Bellingham, Washington,” North wrote.

But one night things took a turn. “Some banditos thought it would be a great idea to hijack a load of their booze,” the manuscript read. A shootout ensued, and “one of the banditos died.”

The brothers-in-law fled and eventually made it back home. North’s autobiography, however, spotlights an enduring mystery, according to his widow, Jan North.

“Who shot that guy and killed him?” she wondered. “Nobody ever did know for sure if that was my father-in-law that shot and killed that person. Or if it was Tony.”

North told her the story a handful of times over the years, though she doesn’t know if he knew more than he shared. But she knows this: After the killing, Charles “stayed the heck away from Tony forever.”

::

Cornero mastered the ocean. Its murk and churn. Its bounty.

He was the ultimate impresario, welcoming 1 million-plus patrons to the Rex in its first year — or so he claimed — and making them feel special as he emptied their pockets.

“He had a photographic memory,” said Ernest Marquez, 97, author of 2011’s “Noir Afloat: Tony Cornero and the Notorious Gambling Ships of Southern California.” “He could meet you one week, a month would go by, and you’d come back — he’d call you by name.”

Cornero remembered the nobodies, but there were plenty of somebodies, too.

Robert Galbreath, whose father captained water taxis to the Rex, recalled him talking about “celebrities that would be on his boat.”

That’s no surprise: Errol Flynn, Cesar Romero and other Hollywood types stopped by. The Saturday Evening Post reported on one high-stakes game of Faro involving legendary gambler Nick “the Greek” Dandolos that drew spectators Carl Laemmle, the founder of Universal Pictures, and Academy Award-winning producer Winfield R. Sheehan.

Ferrying such luminaries to and from the Rex was an exotic gig for Galbreath’s father, then a young USC student in need of part-time work.

“Much better than parking cars,” Galbreath, 81, said.

The elder Galbreath, also named Robert, never shared much about his Rex days but left his son a memento from that time: a yachting cap.

“Revving the engine of a powerful boat, helping fancily dressed flappers in and out, the prospect of big tips — from the perspective of a male college student, it seems like a dream job,” Galbreath said.

Cornero’s FBI dossier tells a darker story about the Rex — one of trick dice, pickpockets, crooked croupiers, gun-toters and bunco men.

According to the Herald Examiner, Cornero called the patrons “squirrels.” It was supposedly a term of affection, but the story said winners “often complained they were beaten and/or robbed,” and “lawmen discovered more than one body washed ashore with a bullet hole in the head.”

Local authorities filed criminal charges against the operators of the Rex in 1938, but not for violence or theft. Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Buron Fitts alleged the Rex was anchored in California waters and thus operating illegally.

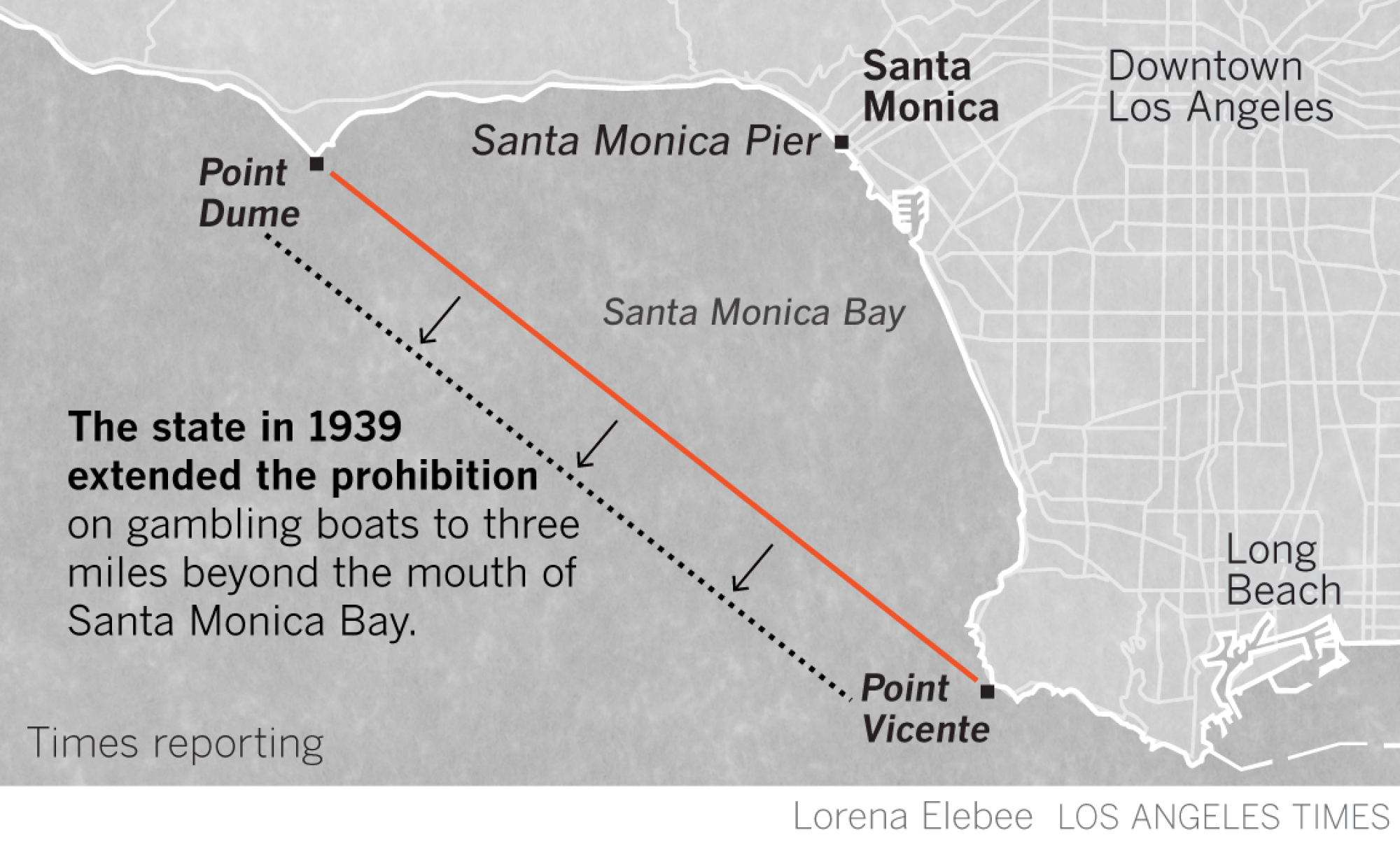

Fitts’ legal team argued that Santa Monica Bay was actually part of the coastline. The prosecutors contended that the three-mile limit for California’s waters should be calculated from an imaginary line in the Pacific connecting the bay’s two headlands: Point Vicente and Point Dume. Under these parameters, the state’s jurisdiction would extend much farther from shore.

After several legal skirmishes, the matter headed to the California Supreme Court. Meanwhile, the Rex kept operating, which seemed to inflame Warren, who’d later dub Cornero “a symbol of the underworld.”

The attorney general hit Cornero and other gambling boat operators with public nuisance charges, which they ignored. That’s what prompted the afternoon raid of Aug. 1, 1939.

The Rex’s top-deck guns stayed silent as 250 government agents approached. But Cornero’s crew barricaded the gangway and flung huge nets over the sides of the ship, according to a United Press account of the drama. The nets could be “maneuvered from the deck as a barrier against anyone seeking to board.” And soon, officers were trying to clamber up the netting.

“Stand off!” Cornero yelled into a megaphone, the United Press reported. “We’re beyond the three-mile limit.”

But the agents kept coming, and two made it to the top of a net. As they tried to pull themselves up onto the deck, Cornero unleashed the water hoses. The officers “tumbled ... ignominiously into the sea” and had to be fished out by their colleagues. The United Press added, “Other officers, attacking in groups, met the same fate, some being helped to it by a seaman’s rough straight-arm to the face.”

But Warren had an advantage: The Rex, converted from a windjammer to a barge, couldn’t move under its own power. Escape was impossible.

Still, at least one member of Cornero’s inner circle tried, according to Grange, whose father served as the vessel’s purser. “My dad apparently jumped overboard and tried to make it back to shore,” said Grange, recalling a story told by an aunt.

Before he leaped, the purser gathered all the money he could and stuffed it in his raincoat, “all the way from his feet to his shirtsleeves,” said Grange, adding: “Just imagine, you’re going to swim three miles, it’s cold water and you’ve got a bunch of cash — what else are you going to put it in?”

His father was apprehended before he got very far.

Cornero was defiant. As the standoff began, he boasted to the press that he had a loyal crew of 200 and plenty of food aboard for his 600 guests. But onshore, The Times reported, friends and relatives of the “temporary prisoners” apparently weren’t assuaged and anxiously milled about the Santa Monica docks with the hopes of an update on the standoff.

Warren, who watched the raid from a beach club — binoculars in hand — was defiant, too, according to the Examiner. “We’ll starve ’em out,” he said.

Nobody’s coming aboard this ship! We’re on the high seas and we’re prepared to defend our rights. Try to use force, and we’ll use it, too.

— Tony Cornero

As the first night wore on, the weather grew colder — and Cornero flashed his characteristic cheek, tossing bottles of top-shelf scotch down to officers on two of the government boats that circled the Rex, according to “Noir Afloat.”

But a U.S. Coast Guard commander assessed the situation more gravely, telling Warren that the patrons needed to be evacuated because “panic might start in [the] night, which would cause loss of life,” according to an FBI report.

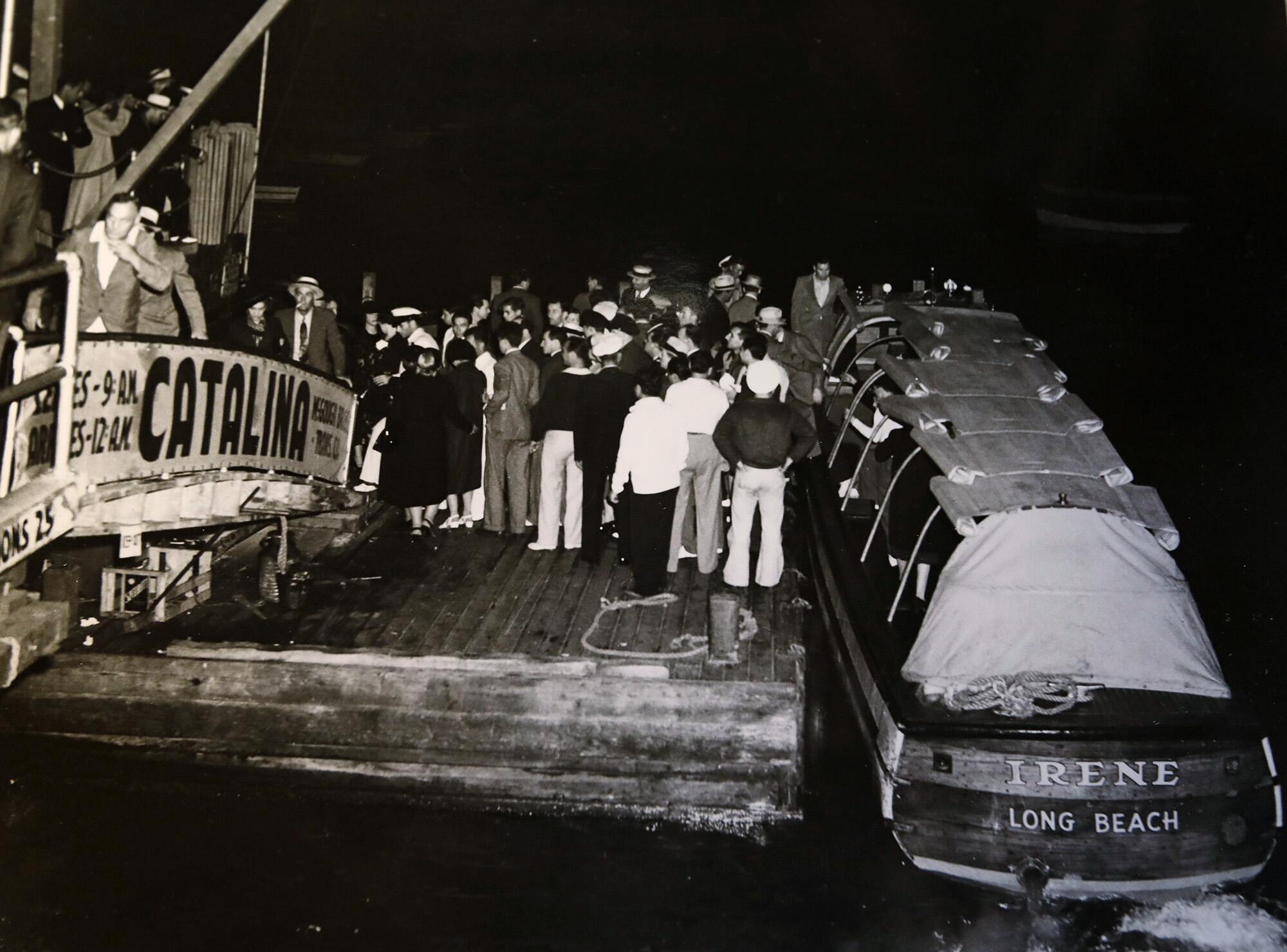

Cornero relented, and the guests were removed. The early-morning evacuation took hours, with the usually efficient water-taxi system becoming “snarled” by the scale of the endeavor, a United Press report said.

It then became a waiting game.

For days, the government boats — which Cornero derided as “Warren’s Navy” — kept circling. At one point, Cornero was said to have hauled down the Rex’s U.S. flag and threatened to raise that of the Empire of Japan. The provocation, Warren told The Times, revealed the “character of the gentleman operating these barges.” (Cornero later disputed the characterization of the episode, telling The Times it was “bull.”)

Though Cornero had boasted, “If I go off, it will be in a box,” after 10 days, he gave up. But he did it with more cheek.

Reaching the pier, he said: “I have to get a haircut, and the only thing I haven’t got aboard … is a barber.”

Cornero soon lost the courtroom battle, too. On Nov. 20, 1939, the state’s Supreme Court sided with Fitts. As a result, California’s jurisdiction was extended about 15 miles from Santa Monica’s shore. The Times concluded: “The day of the gaming ships is done.”

A day later, the Rex, which had sat empty since the battle, was boarded by ax-wielding agents who hacked up craps tables and roulette wheels and heaved the scraps, along with dozens of slot machines, into the ocean. In photos, the pillaging officers’ faces are twisted with emotion — it’s hard to say whether in agony or in glee.

::

Hobbled by the raids and court decision, L.A.’s gaming industry traded ocean waters for desert sand. Cornero opened a modest casino in Las Vegas in 1945, christening it the S.S. Rex Club. But the project was snakebitten from the start, and he returned to L.A. a year later.

He brazenly opened another gambling ship, the S.S. Lux, in 1946 off of Long Beach. It immediately drew the ire of Warren and was shut down after about a month.

Cornero returned to Vegas, defeated but wiser. At a time when many saw gambling as immoral, illegal and impracticable, he understood that success required making gaming acceptable — and accessible — to Middle America.

Cornero helped create the modern-day Strip by conceiving the Stardust, a $10-million resort with 1,065 rooms and an aura of respectability burnished by A-list patrons, including the Rat Pack.

The Strip had mostly attracted the wealthy, but the Stardust featured low-stakes gaming and $6 rooms. This innovation — Cornero’s “volume game” — transformed the city, said Stefan Al, author of “The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream.”

When you think about what popularized Las Vegas and made it what it is today, I think credit is due to Tony Cornero.

— Stefan Al

“It catered to this rising demographic that previously didn’t go there for a vacation — he offered them an affordable one,” Al said. “When you think about what popularized Las Vegas and made it what it is today, I think credit is due to Tony Cornero.”

But he doesn’t get much credit. Maybe because he didn’t live long enough.

Cornero began developing the Stardust in 1954, but construction costs soared. Needing additional funding, Cornero, according to several accounts, borrowed a seven-figure sum from a group of businessmen that included Moe Dalitz, a gangland figure who co-owned the Desert Inn. On July 31, 1955, Cornero met Dalitz at the Inn to discuss the loans, and the conversation turned bitter. Cornero went to the casino to blow off steam.

Shooting dice and sipping a 7-and-7, Cornero collapsed at the table. The 55-year-old was declared dead — felled by a heart attack — shortly thereafter. Supposedly, he was down $10,000.

The next day, Las Vegas Review-Journal reporter Bob Holdorf, who was at the scene, wrote: “Tony died the way he had lived. He died at a gambling table. Probably the … gambler was happy as hell when he felt the surging heat whip across his chest and blot out the world.”

Some observers wondered whether Cornero had been poisoned. After all, he had been seriously wounded when a gunman shot him in 1948 at his Beverly Hills home. Fanning suspicions, Holdorf and others reported that up to three hours passed before the coroner was notified of Cornero’s death, and his body was sent to California without an autopsy.

“No one in Las Vegas was supposed to know Tony Cornero was dead,” Holdorf wrote.

After a power struggle, Dalitz and his associates assumed control of the Stardust, which opened in 1958. Those close to Cornero’s story have drawn their own conclusions.

“I think, and like other people think, he was murdered,” said Marquez, the author.

By the time Cornero died, the Rex was a fading memory. The world had changed. Warren had become chief justice of the United States.

But after hearing about Cornero’s death, Warren expressed something close to fondness for his former adversary: “The crooks don’t seem the same anymore. They don’t have any fun.”

::

Grange, the son of Cornero’s business partner, remembered Cornero’s verve, his intensity. And he’s well positioned to do so.

That’s because he’s the gambler’s godson.

His father and Cornero were best friends and partners, said Grange, whose family then owned Stags’ Leap, a Napa Valley ranch that later became famous for winemaking.

“I don’t think Tony trusted anybody else,” said Grange.

It was, of all things, an agricultural folly that gave Grange a chance to get to know Cornero. Around 1950, Grange’s father moved the family to Brawley in the Imperial Valley for a cotton-farming venture hatched by Cornero, who reasoned that conditions there were similar to those in the South. “Tony was a giant thinker,” Grange said.

Cornero moved in with the Granges. Domestic life didn’t soften his rough edges.

“He just talked real gruff,” Grange said, adding, “I remember Tony trying to be nice, but I don’t think he was.”

As for the cotton, “it didn’t grow very well,” laughed Grange.

Grange, more so than anyone else alive, could explain what drove Cornero. To open the Rex. To dream up the Stardust.

“The money is just the points that you get for playing a successful game,” Grange said. “That’s what he was up to. He would dream up ideas, get into new, cutting-edge things. Hopefully, they make money, but I don’t think that was what drove him.”

It was all just a game. And Cornero could claim a victory.

But the Rex was repurposed as a military supply ship during World War II and sunk off the coast of Africa by a German U-boat. As for its roulette wheels, slot machines and craps tables, they still reside at the bottom of Santa Monica Bay.

Any trace of Tony Cornero’s empire was erased a long time ago.

Any trace except the ocean. He was sovereign there. He was the Admiral.

At least for a little while.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.