Column: Texas court says you can’t force a hospital to give you ivermectin for COVID

A Texas appeals court has just punched a hole in the emerging trend of judges ordering hospitals to treat COVID patients with the drug ivermectin.

“Judges are not doctors,” Appellate Judge Bonnie Sudderth wrote in a unanimous three-judge decision issued Nov. 18. “The judiciary is called upon to serve in black robes, not white coats.”

The appellate panel overturned a trial court injunction requiring a Fort Worth hospital to allow a dying patient to be treated with the drug.

We can give the Joneses our sympathies and prayers, but not an injunction, because the law simply does not permit us to do so.

— Texas Appellate Judge Bonnie Sudderth

The case involved the care of Jason Jones, 48, a Fort Worth-area police officer who was hospitalized with COVID in late September and refused conventional treatments, including the antiviral drug remdesivir.

Jones ended up on a ventilator in the ICU of Huguley Hospital in Fort Worth. As of Nov. 18 he was in a medically-induced coma, with the expectation that his condition is terminal, according to the court decision.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The Jones case was notable because a trial judge ordered the hospital to allow the patient to be treated with ivermectin. It’s one of several lawsuits around the country in which judges have ordered hospitals to clear the way for the treatment.

Most of these cases — including the Jones case — have been brought by Ralph Lorigo, a Buffalo-area lawyer.

Lorigo, who says he has been retained in more than 100 lawsuits in more than 25 states by patients or family members seeking ivermectin treatment, called the Texas decision “terribly wrong.” He said whether to appeal the decision to the Texas Supreme Court is up to the Jones family, which hasn’t yet decided.

Judges are ordering hospitals to give patients Ivermectin to fight COVID-19 despite the absence of evidence that it works.

“I want to take this to the U.S. Supreme Court,” he says of the issue of whether patients should have the right to demand the treatment.

As I’ve reported, this emerging trend of judicial activism has raised concerns in the medical community because no validated scientific evidence exists that ivermectin is at all effective against COVID-19. (A human preparation of ivermectin can be used in limited cases against parasitical diseases and as topical relief for the skin condition rosacea.)

Yet the medicine, most commonly used as a dewormer for farm animals and household pets, has been taken up as a cause by a right-wing claque of anti-government and anti-vaccine activists.

That was behind the Jones family’s insistence that Jason be treated with ivermectin.

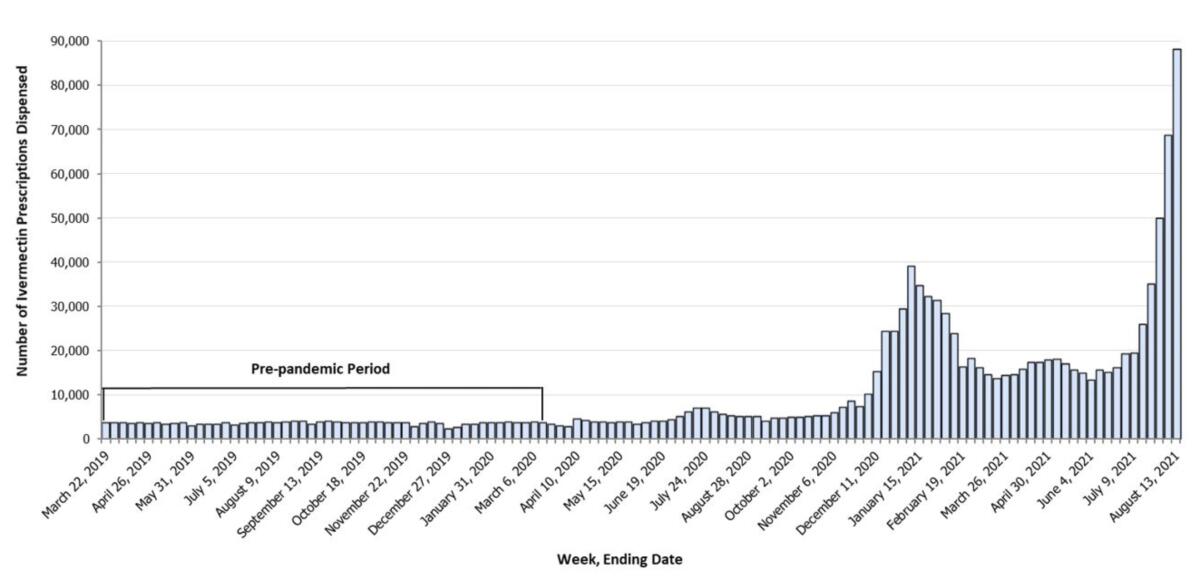

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported that prescriptions for the drug have soared from an average 3,600 a week prior to the pandemic to more than 88,000 by mid-August.

The Texas appeals ruling is a victory for the cause of public health, in that it rejects the notion that patients can demand that doctors and hospitals abandon their professional judgment or that judges can order them to do so. “The judiciary ... must be vigilant to stay in its lane,” Sudderth wrote.

Sudderth took pains to specify that she was not ruling on the efficacy of the drug against COVID-19. Rather, her decision turned on whether the trial judge, and by extension any judge, had the legal authority to order a hospital to perform any particular treatment.

The answer was a resounding no. “The law does not allow this court, the trial court, or any other court to substitute our nonmedical judgment for the professional medical judgment of health care providers,” she wrote.

It’s instructive to run through the steps that landed a comatose Jones in the ICU, for they show how ideologically-inspired medical misinformation can injure or even kill.

To begin with, Jones was unvaccinated, to which the first doctor to treat him at Huguley, Jason Seiden, attributed his “poor state of health,” according to Seiden’s trial court testimony.

Seiden treated Jones with steroids and antibiotics, but Jones refused most of the drugs in Huguley’s COVID treatment protocol. Jones’ wife, Erin, researched alternative therapies and stumbled upon ivermectin. When she asked the hospital to administer the drug, it refused.

Ivermectin, touted as a treatment of COVID by the anti-vaccine crowd, has “no effect,” according to a major study.

Through an online search, Erin Jones then found Mary Talley Bowden, a Texas physician who has been an outspoken opponent of COVID-19 vaccine mandates and promoter of ivermectin.

Bowden was suspended earlier this month by Houston Methodist Hospital, which tweeted on Nov. 12 that she “is spreading dangerous misinformation which is not based in science.” Bowden subsequently resigned from the hospital.

After a telehealth visit with Erin Jones, Bowden, an ear-nose-and-throat specialist, proposed treating Jason Jones with ivermectin and 15 other drugs, none of which has been scientifically validated as a treatment for COVID-19.

After Huguley refused her treatment request, Erin Jones sued the hospital, demanding that if its own doctors refused to use ivermectin, Bowden be granted hospital privileges to perform the treatment herself.

Florida’s new surgeon general, Joseph Ladapo, has questioned the safety of COVID vaccines, despite overwhelming evidence that they are safe and effective.

At a hearing, Bowden acknowledged that she had not examined Jason Jones or reviewed his medical records before writing her 16-drug prescription. She testified, as Sudderth observed, “that this did not matter or change her recommendation for ivermectin ‘because this man is dying.’”

The trial judge instructed Bowden to apply for temporary privileges at Huguley, and ordered Huguley to grant them. The hospital appealed.

The appellate panel was plainly disturbed at the trial judge’s willingness to impose his own will on the hospital’s independent professional judgment, not merely about whether to administer a given treatment, but whether to allow an unvetted physician to practice in its wards.

“A hospital is not a mere hostelry providing room and board and a place for physicians to practice their craft, but owes independent duties of care to its patients,” Sudderth wrote, quoting from an earlier Texas appellate decision.

Nor should judges allow emotion to trump the rule of law, she added.

“We can give the Joneses our sympathies and prayers,” she wrote, “but not an injunction, because the law simply does not permit us to do so.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.