Column: Major study of ivermectin, the anti-vaccine crowd’s latest COVID drug, finds ‘no effect whatsoever’

Ivermectin, the latest supposed treatment for COVID-19 being touted by anti-vaccination groups, had “no effect whatsoever” on the disease, according to a large patient study.

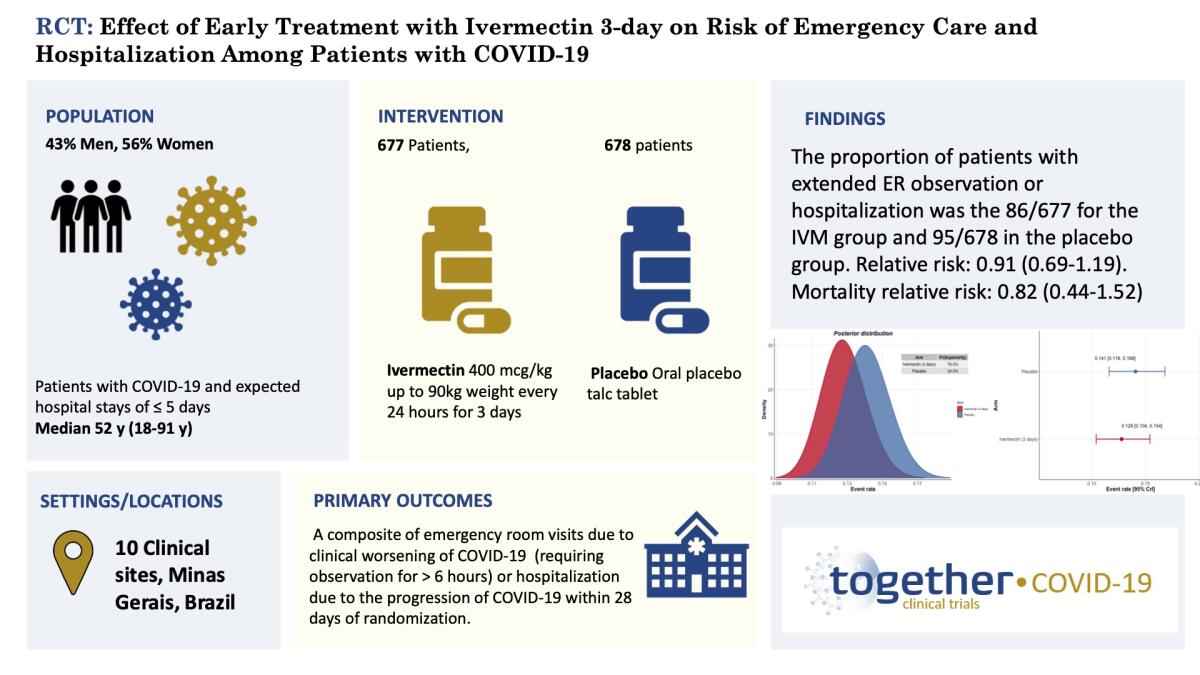

That’s the conclusion of the Together Trial, which has subjected several purported nonvaccine treatments for COVID-19 to carefully designed clinical testing. The trial is supervised by McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada, and conducted in Brazil.

One of the trial’s principal investigators, Edward Mills of McMaster, presented the results from the ivermectin arms of the study at an Aug. 6 symposium sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

I’ve had enough abuse and so have the other clinical trialists doing Ivermectin. Others working in this area have been threatened, their families have been threatened, they’ve been defamed.

— Edward Mills, COVID researcher

Among the 1,500 patients in the study, he said, ivermectin showed “no effect whatsoever” on the trial’s outcome goals — whether patients required extended observation in the emergency room or hospitalization.

“In our specific trial,” he said, “we do not see the treatment benefit that a lot of the advocates believe should have been” seen.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The study’s results on ivermectin haven’t been formally published or peer-reviewed. Earlier peer-reviewed results from the Together Trial related to the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, which had been touted as a miracle treatment for COVID by then-President Trump, were published in April; they showed no significant therapeutic effect on the virus.

The findings on ivermectin are yet another blow for advocates promoting the drug as a magic bullet against COVID-19. Ivermectin was developed as a treatment for parasitical diseases, mostly for veterinarians, though it’s also used against some human parasites.

Its repurposing as a COVID treatment began with a 2020 paper by Australian researchers who determined that at extremely high concentrations it showed some efficacy against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID, in the lab. But their research involved concentrations of the drug far beyond what could be achieved, much less tolerated, in the human body.

The ivermectin camp, as I reported earlier, is heavily peopled by anti-vaccination advocates and conspiracy mongers. They maintain that the truth about the drug has been suppressed by agents of the pharmaceutical industry, which ostensibly prefers to collect the more generous profits that will flow from COVID vaccines.

The problem, however, is that the scientific trials cited by ivermectin advocates have been too small or poorly documented to prove their case. One large trial from Egypt that showed the most significant therapeutic effect was withdrawn from its publishers due to accusations of plagiarism and bogus data.

Nevertheless, the advocates have continued to press their case — without necessarily observing accepted standards of scientific discourse. During the symposium, Mills complained that serious researchers looking into claims for COVID treatments have faced unprecedented abuse from advocates.

As with chloroquine, there’s no reliable evidence that ivermectin works against COVID-19. You can’t censor what doesn’t exist.

“I’ve had enough abuse and so have the other clinical trialists doing ivermectin,” he said. “Others working in this area have been threatened, their families have been threatened, they’ve been defamed,” he said.

“I can think of no circumstances in the past where this kind of abuse has occurred to clinical trialists,” he added. “We need to figure out a system where we have each others’ backs on these issues, because the abuse that certain individuals have received is shocking.” He referred to “accusations” and “swearing,” though he gave no specific examples.

Mills said that his team’s ivermectin trial was altered after advocacy groups complained that it was too modest to achieve the results they expected. The trial originally tested the results from a single ivermectin dose in January this year, but was later changed to involve one daily dose for three days of 400 micrograms of the drug for every kilogram (about 2.2 pounds) of the patients’ weight, up to 90 kilograms.

Half the subjects received a placebo tablet. No clinical results were detected at either dosage, Mills said.

Asked whether he expected further criticism from ivermectin advocates, he said it was all but inevitable. “The advocacy groups have set themselves up to be able to critique any clinical trial. They’ve already determined that any valid, well-designed critical trial was set up to fail.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.