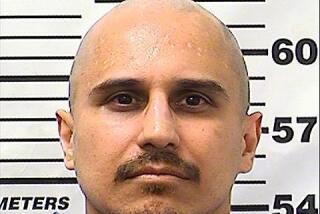

Aburto: Man of Humble Origin, Grand Dreams : Mexico: The confessed triggerman in Colosio assassination ‘wanted to be great,’ acquaintance recalls.

TIJUANA — He surged to international notoriety from the ramshackle migrant neighborhoods of the U.S.-Mexico border, to which his family, like so many others, had journeyed with grand hopes but few prospects.

The naive teen-ager from Mexico’s rural heartland soon became a self-assured border regular, at home in the region’s crowded residential districts, its booming factories and the Los Angeles streets that are its northern beachheads.

But Mario Aburto Martinez wanted more.

The muscular, unfailingly polite 23-year-old chastised peers who wasted their time partying. Instead, he yearned to develop his intellectual potential. Chafing at the grind of Tijuana’s assembly plants, he boasted about mysterious meetings with wise elders. In effect, he lived a double life, sometimes the archetypal hard-working migrant and at others the defiant young laborer grappling with idealistic, semi-coherent philosophies about politics, religion and the plight of the masses.

“He wanted to be great, he wanted to have wisdom,” recalled Hector Umberto Alejo, who took a welding class with Aburto last year. “He read so much his head swelled with thoughts.”

Aburto has confessed to being the triggerman in a crime that probably altered the course of Mexican history: the assassination March 23 of Luis Donaldo Colosio, then considered Mexico’s likely next president. Colosio was shot after addressing a campaign rally in just the kind of Tijuana barrio that Aburto knew so well.

Although Colosio’s head wound was inflicted at point-blank range, Aburto told interrogators, who included Mexican Atty. Gen. Diego Valades, that he had only meant to wound the candidate and draw attention to his pacifist beliefs.

The suspect’s seemingly unfocused political obsessions and his continual striving--his desire to improve himself, to learn from others, to rise above the deadening routine of la frontera --may have ultimately left him susceptible to manipulation by those behind the slaying, friends, relatives and investigators speculate.

There has been no conclusive evidence identifying the masterminds and their motives, only conspiracy theories implicating politicians, drug traffickers or even some kind of shadowy sect.

Mexican authorities say Aburto was helped--and possibly recruited--by at least six co-conspirators, including several security guards who provided crowd control at the rally.

Two of the accused security personnel, both ex-policemen, met with Aburto before the assassination, according to officials and Aburto’s family.

“Aburto may have been the instrument of others,” said Jose Luis Perez Canchola, the Baja California human rights ombudsman who witnessed his interrogation the evening of his arrest.

Those who know Aburto say he is sane, has no criminal past and belonged to no known religious or political organization. Although he frequently discussed politics, no one recalls hearing him express hatred for Colosio or other leaders.

However, in one episode, unknown to friends and family, Aburto’s intellectual and political aspirations came together. He contacted Spanish-language journalists in California, declaring that he had written a lengthy tract on Mexican politics and sought help having it published.

Aburto, who has an eighth-grade education, described the handwritten, 120-page paper as a “reflection on the need for change in Mexican politics,” according to one of the journalists, Raul Camacho Sr., the publisher of El Popular, a Spanish-language weekly based in Bakersfield.

“His vocabulary was rich,” said Camacho, recalling the telephone conversation with Aburto last May. “He sounded quite intelligent.”

Aburto never followed up on Camacho’s offer to review the manuscript, however.

The suspect also spoke to acquaintances of an affection for poetry, music and drawing, although his tastes--he favored Top 40 Mexican bands such as Los Bukis--were unsophisticated.

“He was a worker who tried to improve himself,” said one law enforcement source familiar with the case. “He was sensitive and impressionable. . . . But he wasn’t brilliant either. He could be influenced.”

Under questioning, Aburto contended that he was connected to “various armed groups” throughout Mexico. In offhand comments to friends, he would allude mysteriously to get-togethers with influential mentors.

“He said he was meeting with important people, but he never said who they were,” recalled Alejo, 31, the classmate from welding school.

If investigators have evidence of such meetings, they have not publicized it. The claims about armed groups appear to be boasting or fantasy.

But his father says Aburto told him less than two weeks before the assassination that one of the men now named as a co-conspirator--a former state police commander, Vicente Mayoral Valenzuela--had invited him to a meeting of an apparently political nature and that “delegates” from throughout the nation would be there.

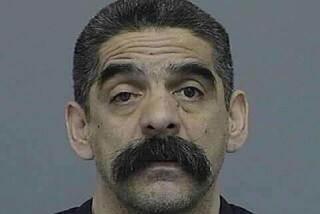

Mayoral, 60, boasted to Aburto of travels overseas and his friendship with a revered former Mexican president, according to Ruben Aburto Cortez, the accused gunman’s father. It was an apparent effort to impress the young man and draw him into the plot, the father alleged in an interview.

“My son always liked to be with older people,” said the elder Aburto, who lives in the Los Angeles harbor community of San Pedro.

Alejo, the classmate, commented: “He had this curiosity to learn. He had the potential to be a leader.”

Another friend recalled how Aburto spent hours talking with an elderly neighbor known as Don Lucio, who spun tales of past exploits as a soldier and presidential bodyguard.

In Mario Aburto’s mind, the mystery contacts may have been paying off. He once flashed an identification card to a longtime friend, explaining that the document offered official protection.

“With this, no one will do anything to me,” Aburto told the friend, who asked to be identified only as Rafael. “I won’t have any problems.”

Arresting officers say they found a credential of the Assn. of Committees of the People, a leftist political group here, in Aburto’s possession. But Eva Sanchez Moreno, coordinator of the grass-roots association that has a membership of 10,000 families statewide, asserts that the card is a fake.

“Mario Aburto was never a member of our organization,” she said in an interview.

Such contradictions crop up again and again in conversations with relatives and acquaintances. What fails to emerge is any clear picture of Aburto’s political thinking or affiliations.

In his first statement to authorities after shooting Colosio, Aburto declared that he wanted to avert bloody incidents such as the Indian rebellion in Chiapas, the southern state that became engulfed in a guerrilla war on New Year’s Day. The Chiapas rebels have denied any connection with or knowledge of him.

Aburto belonged to no political party, officials say. And although he was registered to vote in both Mexico and the United States, relatives say he had signed up in California only in a mistaken belief that being on the voter rolls would somehow help him obtain working papers in the United States.

Aburto’s own statements feed the image of an almost mystical approach to politics.

He told investigators that he had been named an “Eagle Knight,” an Aztec warrior emblem that is an often-used symbol of Mexican nationalism. But he never said who gave him the title or what meaning it held for him.

The Eagle Knight also appears in Aburto’s amateurish drawings, which, authorities say, he kept in a notebook along with rambling, misspelled personal writings.

The suspect’s political fervor was not confined to his notebooks and his musings. He was fired from at least one factory here because of his activism for workers’ rights, friends and officials say. He railed against the exploitative conditions inside maquiladoras , the low-wage, mostly U.S.-owned assembly plants that proliferate in Mexican border cities, manufacturing electronic gadgets, toys, auto parts and other products for export.

“He always took the side of the worker against the bosses,” recalled Alejo, the former classmate. “If he did kill Colosio, I think he did it for the people.”

But the maquiladora assembly lines, with their large female work force, served Aburto as more than a place to earn his keep and develop political consciousness. The cassette tape manufacturing plant that was his last employer and other maquiladoras were fertile ground for his constant search for impressionable new girlfriends--of which, by all accounts, he had many. He told an acquaintance that he wasn’t interested in long-term relationships.

The accused assassin was also preoccupied with staying in shape and keeping his weight down, sometimes eating only a chocolate bar a day, the friend said.

Aburto came to Tijuana when he was 15 from rural Michoacan state in central Mexico, following his older brother, Rafael Aburto Martinez, to settle in a bleak, sprawling neighborhood of steep canyons, muddy streets and hand-built houses known as Colonia Buenos Aires.

Soon after, the entire family relocated to the former squatter’s community on the city’s eastern periphery, one of scores of desert patches now converted to bustling migrant colonies. Then, following the classic migrant pattern, the Aburtos split onto both sides of the international boundary.

The father moved on to San Pedro, the gritty harbor neighborhood where he had previously worked in canneries during the 1970s. Mario and other brothers also spent time there, sharing a flat with their father in a run-down former hotel and working in the Torrance furniture factory where the elder Aburto is still employed.

Mario Aburto was so dedicated to his family, relatives say, that he readily consented when his father and older brother directed him to return to Mexico in 1990 to look after his mother, two younger sisters and a younger brother.

“He was the responsible one, the one who was best suited to watch out for the family,” said Rafael Aburto, 24, the eldest of the six children, who stills lives in San Pedro. “He’s the best of us.”

Aburto was also tough. He did not like people making fun of him, and he did not run from a fight, whether his opponent was a street thug or a factory boss.

“He had a good head on him, but he could take care of business if he had to with his hands, his fists,” said Tony Canchola Jr., a 22-year-old cousin who also lives in San Pedro. “He wasn’t the type to be afraid.”

Recently, Aburto seemed increasingly secretive and distracted. A friend said he was shocked when, three months ago, he visited Aburto at home and found him uncharacteristically hung over after a two-day drinking binge.

“The guy had suddenly changed,” recalled Aburto’s friend, Rafael. “He never smoked or drank” before.

Days before the assassination, Aburto took aside a cousin and showed her a pistol, apparently the .38-caliber revolver that killed Colosio, authorities say. He told her that he would soon benefit from a “profitable” transaction, according to authorities, but said nothing more.

Ultimately, Aburto remains an enigma: a clean-living working man who stepped out of character in sensational fashion.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.