COLUMN ONE : Wrestling’s Star Takes a Tumble : The image of children’s super-hero Hulk Hogan is in peril, and so is that of professional wrestling, as former colleagues tell of drug abuse. His TV denial produced an outcry.

Every weekend, millions of children--and quite a few adults--suspend reality for a few hours, plant themselves in front of the television and wait for the self-proclaimed real American hero to appear.

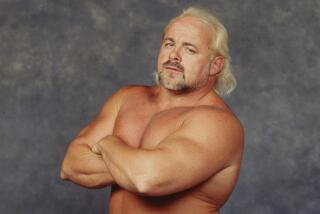

Professional wrestler Hulk Hogan--6 feet, 6 inches and 290 pounds of muscle--bounds to the screen and urges his little Hulksters to say their prayers, take their vitamins and believe in themselves.

Hogan is a Saturday morning cartoon come to life--and the star of a merchandising empire that grossed $1.7 billion last year. Unquestionably the greatest draw in the history of professional wrestling, his status as a role model goes beyond what he does in the wrestling ring.

The Make-a-Wish Foundation, a group that grants wishes to dying children, says he is their most requested personality, and he reportedly visits as many as 20 sick children a week. He has starred in two movies, both aimed at children, and played “Thunderlips” in Rocky III.

Hogan is in demand as a celebrity spokesman, doing commercials for Right Guard, Honey Nut Cheerios and Hasbro wrestling figures. There are almost 300 official Hulk Hogan products, all aimed at children, from dolls to vitamins and pillowcases.

But Hulk Hogan’s image is in peril, and so is that of all of professional wrestling. Hogan is accused of having abused steroids and cocaine. And professional wrestling is said to be rife with steroid abuse, at the very least.

For Hogan, whose size and rise seem to personify what professional wrestling has become in America, troubles mounted when he turned up on Arsenio Hall’s television show to quash reports that he was a heavy steroid user. He declared that he has only used steroids on three occasions--all under doctor’s care to rehabilitate muscle injuries.

The outcry was immediate. Former wrestlers came forward to say Hogan was lying. They say they have personal knowledge of his drug abuse. They say you can’t make it big in professional wrestling without drugs.

The need to be massive and muscular is now de rigeur for professional wrestlers and, with the constant travel, that can require some extra help. Not to mention the relief many seek for the pain from the sport’s bumps and falls.

“Valiums, placidyls, acid, pot, steroids, cocaine, alcohol are all a major part of professional wrestling,” said Billy Jack Haynes, a former World Wrestling Federation wrestler who now competes independently. “It’s all brought on by the promoter because he asks too much out of you. You’re only a human being, but you’re just a number to him.”

Ivan (Polish Power) Putski (real name Joseph Bednarski), a former wrestler, says of steroids: “It’s something you have to do. I didn’t want to take them but I had to because I didn’t want the other guy to look better than me. . . . It’s a vicious circle until you retire.”

Professional wrestling for years was a backwater form of entertainment concocted by television in the 1950s. The country was divided into regions, all with local promotions.

The setting was usually small, smoky arenas, usually before a few thousand people. Wrestlers would travel, often in the same car, from town to town renewing their rivalry in the same manner--and with the same ending--as the night before.

An American passion play of good versus evil, the “sport” drew upon stereotypes left over from the war--the Japanese, German and Russian wrestlers were always bad. Wrestlers were usually portrayed as back-room brawlers or scientific wrestlers--meaning those who didn’t cheat. There were no superhuman figures, only good ol’ boys who could give and take a solid punch.

Everything changed in the early 1980s, compliments of Vince McMahon Jr. The son of a longtime promoter in the Northeast, McMahon took advantage of cable television and went national with his World Wrestling Federation. He signed a deal with the USA cable network and syndicated his show through the country.

In 1984, McMahon tied wrestling to rock music--using MTV and rock stars such as Cyndi Lauper--and cultivated a new and predominantly young audience. What he needed was a star bigger than life. And so began the rise of Hulk Hogan.

It was in 1985 that McMahon broke open the sport with a risky closed-circuit venture called Wrestlemania. He brought in television actor Mr. T to tag team with Hogan against two bad guys. He engineered the pair onto “Saturday Night Live” and David Letterman’s show, and suddenly wrestling was the campy new entertainment of yuppies.

McMahon arranged to get a wrestling show on once a month in the “Saturday Night Live” time slot. Wrestling took off. Merchandising was cranked up on a large scale as McMahon marketed to kids with action figures, championship belts and clothing. According to industry magazines, the WWF did more in gross merchandising last year ($1.7 billion) than the NFL. Today, the company is said to be worth somewhere between $150 million and $500 million.

But the WWF’s claim to presenting “family entertainment” has been tarnished by several embarrassing incidents.

Texas Tornado, whose real name is Kerry Adkisson, was arrested in Richardson, Tex., for allegedly forging drug prescriptions. He has entered a drug rehabilitation program, and his case is pending. Marty Janetty (half of the tag team The Rockers) was arrested in Tampa, Fla., for possession of cocaine, drug paraphernalia and resisting arrest; the case is pending, and he is wrestling in Japan.

Last month, officers from the St. Louis Police Department conducted a surprise inspection of wrestlers’ luggage and clothing, accompanied by drug-sniffing dogs, as part of an ongoing investigation into drug use by WWF wrestlers. No drugs were found.

Perhaps the most damaging blow for the WWF came during the June, 1991, trial of George Zahorian, a Harrisburg, Pa., urologist who was convicted on 12 counts of selling steroids for non-medical purposes.

Hulk Hogan (whose real name is Terry Bollea) was subpoenaed because he was one of the five wrestlers to whom Zahorian was accused of selling steroids. But the U.S. attorney agreed to waive Bollea’s testimony because his “private and personal” matters outweighed any possible contribution to the trial. Wrestlers Roddy Piper (real name Roderick Toombs), Brian Blair (his real name), Rick Martel (Richard Vignault) and Dan Spivey (his real name) all admitted to buying steroids from Zahorian. In addition, Zahorian testified that he treated Bollea as a serious steroid abuser and successfully got him off steroids.

Federal Express records obtained by the grand jury in the case show that Zahorian sent packages to Bollea on eight occasions during a nine-month period in 1988. Thirty-four packages were sent during the same period to the WWF’s headquarters--which has an unlisted phone number--in Stamford, Conn. An additional eight packages were sent to McMahon at other addresses. The four wrestlers who testified all admitted receiving steroids from Zahorian by Federal Express.

McMahon, who also heads the World Bodybuilding Federation, acknowledges he experimented with steroids for a short time and received them by Federal Express from Zahorian. However, he says they were legal at the time and he does not condone their use. Possession of steroids for non-medical purposes has since been made illegal; the Food and Drug Administration reclassified the drugs under the Controlled Substance Act in 1991.

A furor erupted in the wrestling community two weeks after Zahorian was convicted. Hogan went on the Arsenio Hall show to repair his image. “I am not a steroid abuser,” he declared, “and I do not use steroids.”

McMahon says of Hogan’s television appearance: “I think Hulk told the truth, but maybe not the whole truth.” Hogan declined to be interviewed, a WWF spokesman said. Others, claiming first-hand knowledge of Hogan’s drug use, are not so reticent.

“I compare Hulk Hogan to (former Washington, D.C., Mayor) Marion Barry,” said Superstar Billy Graham (whose real name is Wayne Coleman), the one-time villainous heavyweight champion of the World Wrestling Federation. “Barry went to schools and talked to kids about not doing drugs and at the same time had crack cocaine in his pants pocket. Hogan is a liar to the children, because all the time he is saying ‘I’m not using steroids.’ I think that was the most disgusting thing you could do in this country with the drug situation the way it is.”

Graham admitted his own steroid abuse a few years ago after having several hip and ankle operations that he attributes to degenerating bone and muscle tissue caused by steroids. Now Graham lectures at schools about steroid abuse.

Graham recently appeared on the “Cody Boyns Wrestling Show” on WALE-AM in Providence, R.I., taking a call he says he’ll never forget.

“This young girl called me and started crying,” Graham said. “She asked me, ‘Why is Hulk Hogan lying to us?’ I didn’t know what to say.”

Hulk Hogan’s life out of the wrestling ring as Terry Bollea is a long way from his modest beginnings. His home is a large, two-story structure adjoining the Intercoastal Waterway in Clearwater, Fla., where he lives with his wife, Linda, and two children, Brooke, 3, and Nicholas, 1.

“I’m in love with my kids, I’m in love with my wife, I have lots of friends,” he told People magazine last year. “When there’s a negative I run right over it.”

Born in Augusta, Ga., in 1953, he weighed in at a formidable 10 pounds, 7 ounces. His father, a construction worker, and his mother, a housewife and dance teacher, moved the pre-Hulkster to Tampa when he was 3. He was a star pitcher on his Little League team when he was 12 but found trouble at 14 and was sent to the Florida Sheriff’s Boys Ranch for street fighting.

After high school he spent a few years playing bass guitar at local clubs in the Tampa area.

Through those years, he maintained an interest in wrestling. Superstar Billy Graham first met Hogan in late 1976 in Tampa.

“He would be at the (Tampa) Armory every Tuesday night watching the wrestlers and appearing mesmerized,” Graham said. “He would end up going to the Imperial Room and visit with the wrestlers. I was his hero. I was the one with the big arms and he befriended me and wanted to know what kind of steroids I was taking. He wanted to get into wrestling and there was no reason for me to deny him the information.”

Bollea started wrestling in 1978 in smaller cities in the South under the name Terry (the Hulk) Boulder and met up with David (Dr. D) Shults in Pensacola, Fla. Shults, currently a bounty hunter and private investigator in Connecticut, says he let Hogan stay at his house and, in exchange, Hogan gave him steroids. Shults says Hogan would also sell steroids to other wrestlers.

“I personally gave him shots hundreds of times--not a few times, hundreds of times,” Shults said.

Hogan continued to wrestle in the South as a heel (the bad guy) but changed his name to Sterling Golden. He got a major break in late 1979 when he went to New York and Vince McMahon Sr., father of WWF’s founder, renamed him The Incredible Hulk Hogan. He made it to main-event status but, as the villain, always lost.

In 1980, he was arrested in New Jersey for possession of a firearm. He entered into a pretrial intervention program, served six months’ probation and the felony charge was dropped.

Hogan moved to the American Wrestling Assn. in the fall of 1981 and after a few months was turned into a babyface (the good guy). In 1983, as his popularity was on the rise, he appeared in Rocky III.

Barry Orton, who wrestled under the name Barry O, recalls in his unpublished book “Wrestling Babylon” his associations with Hogan. In 1983, “I ran into him (in Las Vegas) and he was really friendly, asking about my brother Bob (also a wrestler) and this and that and he asked me, ‘Can you get some coke?’

“It so happened that I knew someone and so I gave that someone a call and that someone showed up soon thereafter. It became a regular thing. . . . It was a routine. Hogan, of course, wasn’t the only customer. After the matches we’d all go up to a room and indulge.”

Graham remembers another incident in 1983 when he was on a charter flight from Minneapolis to Green Bay. “I remember this one flight during which Hulk said, ‘Superstar, would you like to try some cocaine?’ I said ‘I’d really prefer not to . . . ‘ He said, ‘You’re right. Don’t start taking cocaine, because it is the hardest drug in the world to get off of because it is so good.’ After that lecture, he proceeded to put about three or four lines up his nose.”

Hogan moved back to the WWF in 1984 and in his first match that January won the world title by beating the Iron Sheik.

Hogan was never more popular than at Wrestlemania III in March, 1987, when 90,817 filled the Silverdome in Pontiac, Mich., to watch Hogan defeat his last great adversary, Andre the Giant. That year, Graham said, on three occasions--in Detroit, St. Louis and San Francisco--he injected Hogan with steroids.

Hogan was wild and unpredictable that year, recalls wrestler Billy Jack Haynes. He remembers after one card at Madison Square Garden, he was going to Hogan’s home in Connecticut to spend the day off.

“He was driving and going about 80 miles per hour and they (Hogan and two other wrestlers) were drinking and smoking joints,” Haynes said. “I told Hogan that he was crazy and if he were stopped with all the drugs on him his career would be over.

“We finally got to his house about 4 a.m. and he came into the bedroom where I was and he apologized to me. He said, ‘You’re absolutely right, man, I can’t believe I was doing that.’ ”

In 1988, Hogan started to cut back on his wrestling schedule, generally working weekends and major pay-per-view cards. As the biggest name in the prospering professional wrestling world, he was reportedly able to dictate when he wanted to work. At the same time, he pursued a movie career, starring in “No Holds Barred,” a movie about a wrestler.

Today, Hogan’s income is a closely guarded figure. Estimates range between $2 million and $6 million a year, including merchandising fees. But his career in the United States may be over after next month’s Wrestlemania VIII pay-per-view event. Promoter McMahon said Hogan is taking an indefinite hiatus.

“It might be for six months, it might be for a year, it might be forever, we don’t know,” McMahon said, denying that adverse publicity has any bearing on Hogan’s decision. “Hulk Hogan, the character, will always be associated with the WWF. Whether Terry Bollea will be is a matter of conjecture.”

Hogan is said to be negotiating several appearances to wrestle in Japan for as much as $100,000 a match. But his career as a commercial spokesman appears at risk of collapsing.

Allegations of drug abuse “will end his career as a spokesperson for any product,” said Nova Lanktree, one of the country’s leading experts on sports merchandising. “If it is true that he is on steroids and other drugs and has denied taking steroids publicly, then no company or advertiser will touch him.”

What now for professional wrestling if its biggest star takes the biggest tumble of his life?

Controversy is expected to mount. ABC’s “20/20” is scheduled to air a segment next week about steroid abuse in professional wrestling. Tabloid television shows such as the syndicated “Now It Can Be Told” have been interviewing some of the Hogan’s accusers.

The WWF’s problems extended beyond the issue of steroids and other drugs. Last week, two bookers--the people who decide who wins and how--resigned “in the face of various unsubstantiated allegations, as well as unfair media pressure brought on the organization,” according to a press release from the WWF. The resignations came less than a week after the New York Post reported that a lawsuit will be filed in New York federal court alleging that some male WWF executives and administrative employees sexually harassed and abused teen-age boys working as ring assistants. No lawsuit has yet been filed.

Dave Meltzer, editor and publisher of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, considered the bible of professional wrestling, thinks the World Wrestling Federation will survive despite tough times ahead.

“It would be devastating to the WWF to lose Hogan,” Meltzer said. “But as far as killing the company, it would take something really, really major. As long as they have television, wrestling will survive, even if they think everyone is using cocaine. People thought that of the NBA a few years ago and they didn’t go out of business.”

WWF owner McMahon dismisses the notion that professional wrestling faces an image crisis.

“I do not perceive there is a crisis here, whatsoever,” McMahon said. “I think it’s one largely in part due to media talking to media talking to media. Business and attendance are up, licensing is terrific.”

And McMahon argues that he is cleaning up his organization. Testing for street drugs, he says, began in 1987. In November, four months after the Zahorian trial, steroid testing was instituted. Initially, McMahon says, half the WWF wrestlers tested positive for an anabolic steroid metabolite, but that number is now down to 15%.

McMahon calls the WWF’s drug testing program “the most comprehensive in the world.”

Mike Tenay, host of the nationally syndicated radio show “The Wrestling Insiders,” which broke some of the stories about drug use, sees things differently: “Hulk Hogan and the WWF didn’t come clean with the public and that’s why they’re in this problem. . . . They did not address that they have internal problems. All these so-called unbeatable drug tests have been laughed at. People can see with their own eyes that steroid use is prevalent. People believe that the WWF is just not telling the truth.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.