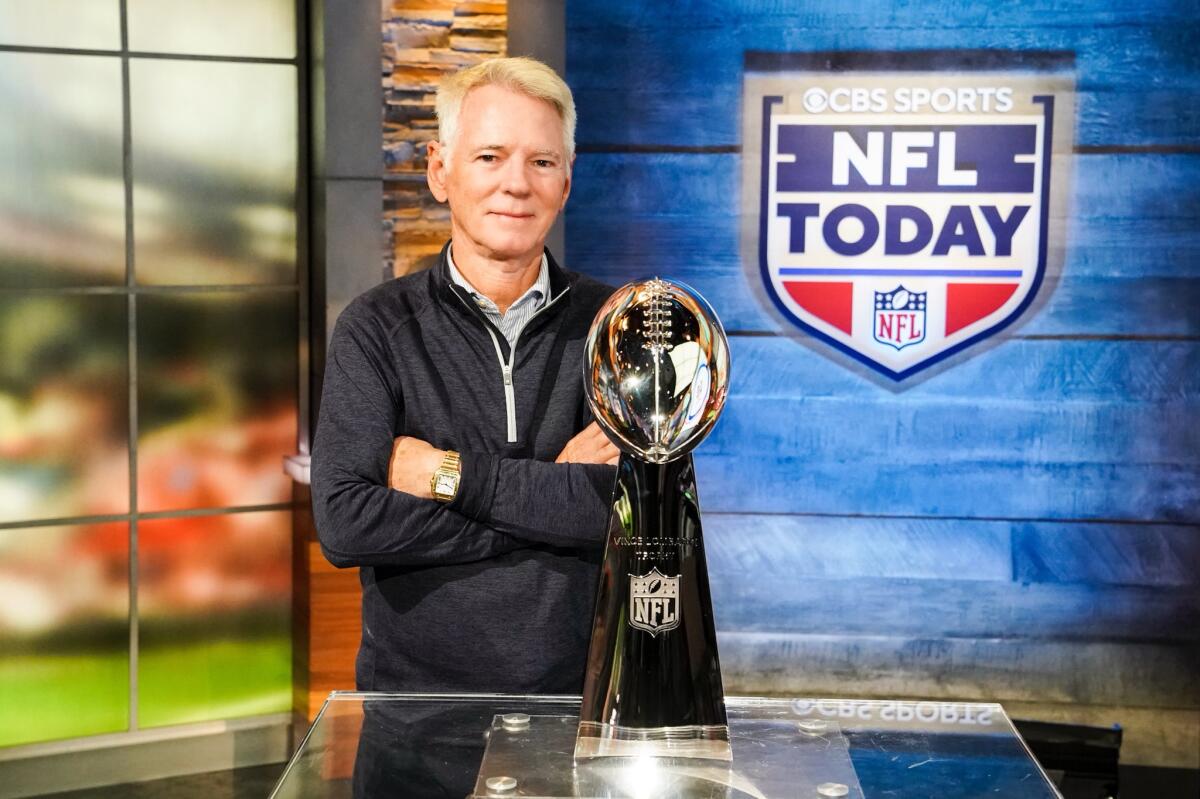

In his last Super Bowl, CBS’ Sean McManus reflects on ‘the ultimate TV drama’

CBS Sports Chairman Sean McManus has a bit of trouble recalling the first Super Bowl he ever attended.

It may have been 1980 when the Pittsburgh Steelers defeated the Los Angeles Rams at the Rose Bowl, he said during a recent conversation at his office on Manhattan’s West Side.

But when you’ve spent much of your life in control rooms and trailers for major sporting events since working as a 12-year-old production assistant at the Jacksonville Open for $25 in cash, it’s hard to keep track.

On Sunday, he will oversee the CBS telecast of Super Bowl LVIII, when the defending champion Kansas City Chiefs take on the San Francisco 49ers at Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas. It will be McManus’s ninth and final trip to the Big Game in the executive role he has held since 1996.

McManus, 68, is retiring in April following CBS’ coverage of The Masters golf tournament, capping a career that spanned much of the history of TV sports. (He will be succeeded by his second-in-command David Berson).

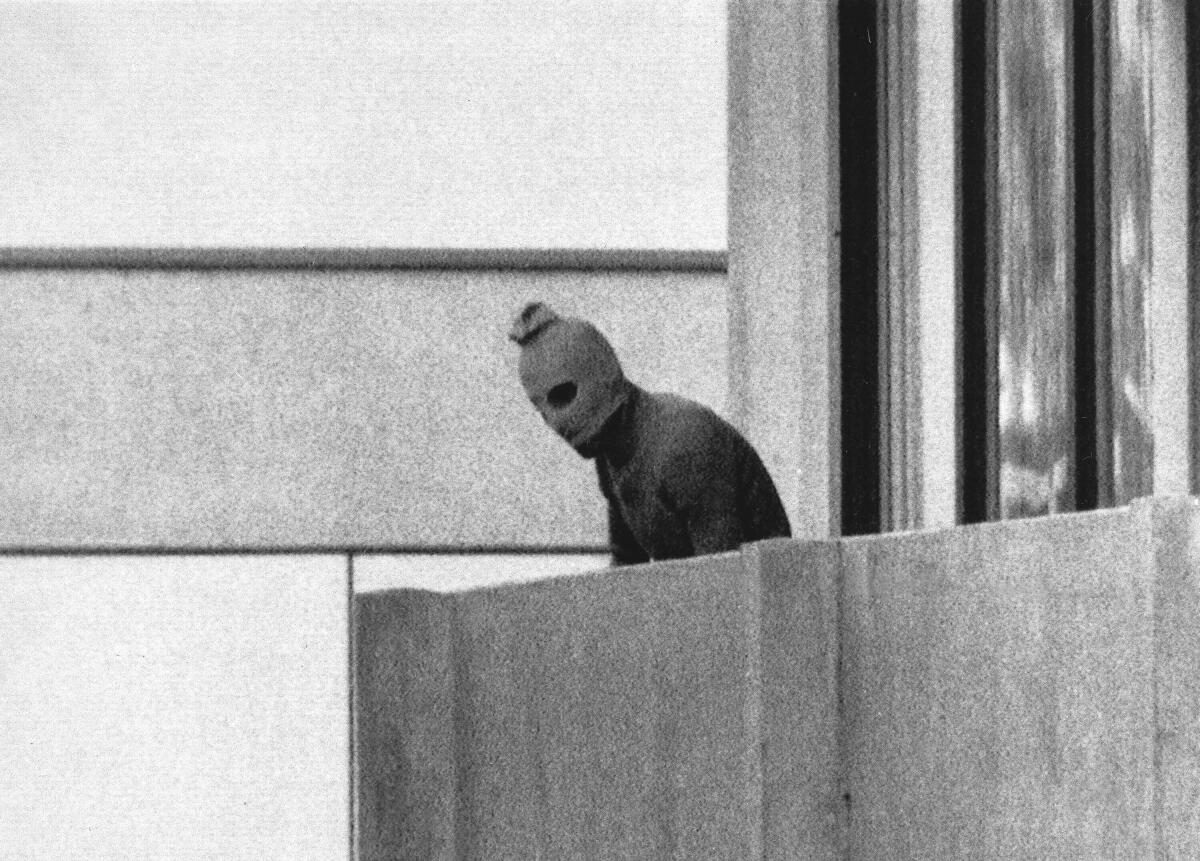

He is the son of Jim McKay, the legendary ABC Sports broadcaster who hosted “Wide World of Sports,” the anthology program that brought events that ranged from barrel jumping to world champion heavyweight fights into the nation’s living rooms during the 1960s and ’70s. A teenage McManus was in Munich, Germany, for the 1972 Summer Olympics, where McKay reported on the killing of 11 Israeli athletes by Palestinian militants.

After stints at ABC, NBC and IMG, McManus arrived at CBS Sports in 1996 when it was in a distressed state. Two years earlier, CBS lost the rights to its NFL package, outbid by Rupert Murdoch’s then-nascent Fox network.

The departure of the NFL devastated CBS, which lost its perch as the top-rated network, and put Fox on the map, an early demonstration of the league’s impact in the television ecosystem that has only become mightier over time.

The NFL is now a key driver in shaping the streaming video landscape, as evidenced with the playoff game exclusive to NBC’s Peacock and the plans for a new streaming platform formed by the league’s media rights holders Fox and ESPN in partnership with Warner Bros. Discovery.

McManus successfully led the negotiations for CBS to get the NFL rights back in 1998. It helped turn around the network, which became the most-watched for the next two decades. McManus has been along for entire ride, including a six-year stint when he oversaw news and sports — a dual role only replicated in broadcast TV by ABC’s Roone Arledge.

McManus has been in the control room for 27 Masters and NCAA men’s basketball tournaments. He sat alongside two former U.S. presidents at the memorial service for legendary CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite.

But his fondest memories will likely be the hundreds of weekends he spent at the Manhattan-based CBS Broadcast Center, which served as a command center for the network’s NFL coverage. On his final day during the regular season, he was surprised by staff with a chocolate cake with the icing inscription “NFL Sundays Will Never Be The Same” and a signed football from the “NFL Today” panel.

Before heading to Las Vegas, McManus shared some recollections about his career and thoughts about the weekend ahead. This interview has been condensed for clarity.

Do you remember the first time watching your father on TV?

The Masters in 1961. So I was 6 years old. I was watching it with my mother and I was very confused because my father identified himself as “Jim McKay.” And I didn’t quite understand McManus-McKay at the time. But my mom explained it to me.

It’s wacky that he had to change his name to get a job on a show called “The Real McKay.”

He was happy to do it because he was looking for work. I remember watching a lot of “Wide World” events. I remember the U.S.A.-U.S.S.R. track meet broadcast from the Soviet Union in those days.

Muhammad Ali fights were a staple of “Wide World.” Did you get to attend any?

Well, the No. 1 sporting event on my list is Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier I (in 1971). I had gone to Ali’s other fights. I really wanted to go and my dad got me a ticket. And I was there in the fourth row. Frank Sinatra was running around being the official photographer for Life magazine. From a social standpoint it was probably the biggest sporting event to that day. You can’t overestimate how big it was. Not the center of the sports universe; the center of the universe. It was Ali who was the rebel, and people considered him a draft dodger. And then there was Joe Frazier.

People believed he represented the establishment.

I remember the ring introductions and when Ali went in, there were some boos because in those days, the Black Muslims were not exactly accepted.

You were with your father in the ABC Sports studio in Munich when he reported on the tragedy at the 1972 Summer Olympics. What kind of impression did that leave on you?

First and foremost it elevated the respect I had for my father, because I saw what he went through for more than 12 hours being on live television. None of us there understood the impact that it was having in the United States. Remember, there was no cable news, no CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, no internet, no social media. So the only avenue of information was through ABC and through my father. And if you put it in a historical perspective, people didn’t talk about terrorism; it wasn’t part of our vernacular. It was probably the first international acts of terrorism to actually get live coverage.

Do you remember the public’s response to him?

When he returned, there were duffel bags of letters that people had sent to ABC Sports. For the rest of his career when people came up to him they would say, “I’ll always remember 1972.” And today when people come up to me and say, “I was a big fan of your father’s,” 90% of the time they will say, “1972 is memory that I’ll never forget.”

Jim McKay’s words that day are part of broadcasting history.

He said, “My father always told me that our greatest fears and greatest hopes are never realized. Well, today our worst fears were realized.” And then he gave the news about all the Israelis being killed. And then he just paused and said, “They’re all gone.” Along with Walter Cronkite, when he took off his glasses and announced the death of JFK, I think you can make the case that those are certainly among the most famous words ever said on television.

You came up at ABC Sports with some big names and a few characters who could be pretty rough on the furniture back in the day.

I think Don Ohlmeyer and Roone Arledge are probably the two best sports producers in the history of sports television. And (ABC Sports producer) Chuck Howard is right up there also. With Chuck, I got yelled at pretty much constantly while doing graphics for ABC Sports. I was a production assistant so I was the low man on the totem pole, worrying about everything from music for the show, to graphics, to booking the limousines and hotels for the talent and the production team. So I really learned trial by fire. Even though I had known Chuck from the time I was probably 9 years old, he still treated me like every other PA, which was to yell, and unfortunately in those days, humiliate you. Whether you were male or female, or son of Jim McKay, it didn’t matter, you got it.

Were you ducking any flying objects?

Chet Forte, (the first director of “Monday Night Football”) was known for throwing his headset against the monitor wall. There were always two or three extra headsets for Chet.

So let’s fast-forward to 1995 when you get a call from Peter Lund, then-president of CBS, about coming over to run the sports division. How did you convince him that you could get the NFL rights back for the network?

I didn’t try to convince him because I didn’t have a great amount of confidence that I could deliver. Only one network ever had NFL football and given it up, and that was CBS. The effects were devastating. So in my wildest dreams it was tough for me to imagine any of the current NFL TV partners would agree not to renew a football package. It was by far my primary goal by 100% was to get the NFL back and I thought about nothing else for a year and a half.

What was the key to making the deal?

Once the negotiating process started, we had the right strategy, which was to try to convince the NFL to do the American Football Conference package first because NBC (the AFC rights holder at the time) was going after “Monday Night Football.”

When we made our offer of $500 million a year, NBC passed with the hope that they would get “Monday Night Football.” I immediately signed the deal so that it was official, and then the celebrations began. And it was by far professionally, you know, the most satisfying moment of my life.

It’s been said the move saved CBS at that time.

I don’t want to say that, but in many ways it helped, yes. We went to being No. 1 again. When everybody accused us of overbidding, Mel Karmazin (then-CBS Corp. president) said, “If I can make a dollar on the NFL it’s worth it.” And we made money every year of the deal. Same story as with Rupert Murdoch. Everybody thought he was crazy and he built a network on the back of the NFL. When you saw what happened to CBS and Fox it really was the first real establishment of just how powerful the NFL would become.

The Super Bowl was always the most-watched broadcast of the year. But there was a time when there were some pretty big swings in the number-driven team matchups and the competitiveness of the game. That seems to matter less now. How did the game become part of the culture?

It became America’s holiday, a chance for everybody to sort of forget any of the problems that were going on in their personal lives or in the world. And it just really became a celebration, halftime, and the fear of missing out is very prevalent. You want to be able to talk about the commercials, and the halftime show, and who won the game. And today the NFL is a 12-month-a-year, 365-day story.

If you watch cable sports coverage in April or March, or even June and July, more often than not one of the lead stories is the NFL. A player being traded, a coach doing this, an owner doing this. It gets an enormous amount of coverage, more than any other sport, because it’s so popular. And it’s so popular because it gets more coverage. And it just feeds upon itself. It’s the ultimate TV drama.

Speaking of drama, and perhaps one of the scariest nights of your career, how did you react when the power went out in the Superdome during Super Bowl XLVII in 2013?

I thought if the game is being played and we’re not covering it, that is an unmitigated disaster of epic proportions. Do you stop the game because America can’t watch it? What about, in those days, the $4 million commercials? The stadium was black; we had to deal with the fact that we had no communication. Couldn’t talk to (CBS Sports lead announcer) Jim Nantz. Didn’t know if people could hear Jim. We were pretty roundly criticized for our coverage, but for the first 10 minutes we just had no idea how to communicate with anybody. The NFL wasn’t talking. The stadium authority wasn’t talking, so it was really difficult. Once we found out that it wasn’t CBS who caused the problem there was a feeling of relief. Then there was a feeling of, ‘What happens if the power never comes back on?’ What’s the financial liability? Do they play it Monday night? And, you know, what happens to the ratings? And how many tens of millions of dollars are we going to lose?

On top of all that were you wondering if it was a terrorist attack?

That was the first thought, yeah. I had my family in the stands. So it was traumatic and terrifying. Fortunately, for whatever reason, it gave some motivation to the San Francisco 49ers and they came back in the game and made it a thrilling, close game. It looked like it was going to be a rout for the Baltimore Ravens.

Your 2016 deal for the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, which put every game across CBS and Turner’s cable networks, recognized how the audience was going in the consumption of sports on TV. How did you imagine it?

Well, first I imagined the present, which wasn’t working. Splitting the country into eight different regions and simultaneously showing four games at one time wasn’t pleasing anybody. The viewer got mad and wanted to be able to watch all the games however they wanted to, So I knew we needed a partner. Turner Broadcasting’s David Levy was a friend. And I looked around and I saw, ‘Well, they’ve got many cable channels — imagine what would happen to TruTV if they had a Kentucky basketball game or an opening-round game?’ So it was a process of necessity, because if we hadn’t found a partner, ESPN was going to buy it. We were not going to be able to sell the traditional way of covering the tournament.

You said publicly that you were hoping for a Super Bowl with the Kansas City Chiefs, who have exploded in the pop culture thanks to Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce. How much will it impact the rating on the game?

Well, the Super Bowl’s going to get what it’s going to get. Kansas City, if you look at research, is the No. 1 team in terms of drawing fans. Patrick Mahomes in many ways is still the face of the NFL. So from that standpoint it helps. I’m not going to minimize the fact that the Taylor Swift phenomenon will be part of the storylines. There’s always multiple storylines going into a Super Bowl. It will increase interest among people who maybe don’t have interest in the Super Bowl. It just reconfirms what we’ve been talking about here. The No. 1 performer in the world shows up at some football games and it’s a huge phenomenon. It just adds to our overall theme that there is nothing like the NFL in this country. .

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.