He drank serpent blood in Vietnam and had armed guards in Bulgaria. Bringing U.S. investors to Myanmar was ‘a bridge too far’

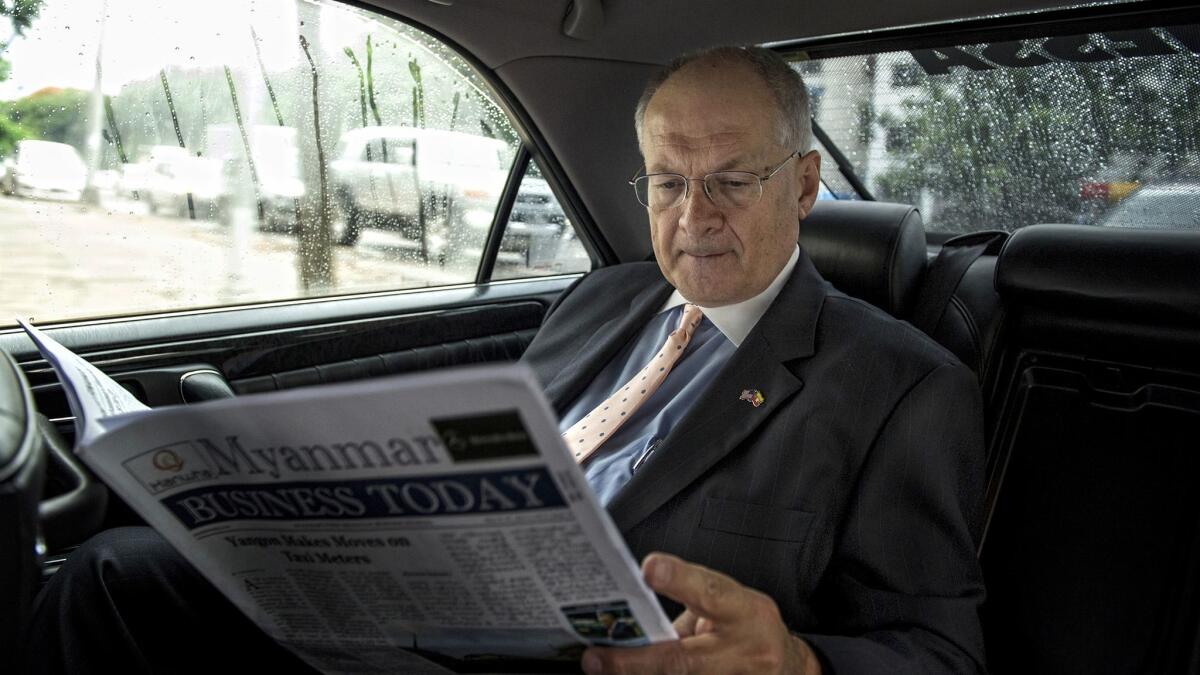

Reporting from MUMBAI, India — In 2013, Eric Rose opened the first American-owned law firm in Myanmar and invited 500 diplomats, politicians and business leaders to a luxury hotel to celebrate.

The country had long been one of Asia’s most isolated economies, but a transition from military rule to democracy held the promise of major investment by U.S. companies — and plenty of legal work to guide those transactions.

That promise has been slow to materialize, and last month, after nearly five years, Rose handed off his clients, closed shop and let employees take home the office furniture.

Rose’s departure was the latest sign of how Myanmar has lost its luster for U.S. investors, who say the military has relinquished little power and Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratically elected government has failed to loosen the grip that army generals and their cronies retain over key industries.

Regional countries with deeper ties to Myanmar have gobbled up most of the opportunities: Businesses from China have invested $5.7 billion and Thailand nearly $1 billion over the last four years, according to government statistics, while U.S. companies have officially spent just $133 million, although that does not include money funneled through branches in Singapore.

The army’s massacres of Rohingya Muslims, which have sent nearly 1 million refugees fleeing into neighboring Bangladesh since August, have added a severe reputational risk for Western companies, Rose said.

“The unfortunate reality is Americans aren’t coming,” Rose, 63, said from his house in Washington. “I just don’t see light on the horizon.”

The independent Myanmar Times newspaper called the withdrawal of his firm, Herzfeld Rubin Meyer & Rose, “a vote of no confidence” in the economy. The nation’s growth rate slowed last year from 7.3% to 6.5% largely because of a decline in foreign investment, according to the World Bank.

“Eric was more bullish than anyone on Myanmar,” said Murray Hiebert, a senior associate in the Southeast Asia program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

“Here’s this 52-million-person economy that had been pretty closed off and now there’s an opportunity. But it was getting clear, even early on, that this was going to be a tough place to do business.”

After ruling Myanmar, also known as Burma, for nearly half a century, the army in 2011 began democratic reforms that paved the way for Suu Kyi, the long-jailed opposition activist, to lead her party to victory in national elections four years later. The generals pledged to reduce state control of key industries and opened the economy to more foreign investment.

President Obama responded by lifting long-standing U.S. sanctions “to ensure that the people of Burma see the rewards from a new way of doing business, and a new government.”

Many in Myanmar say the U.S. failed to live up to that promise.

The Treasury Department still subjects financial institutions in Myanmar to extra reporting requirements under the Patriot Act, a demand that applies to only three other countries: Cuba, Iran and North Korea. The measures, which aim to fight money laundering and terrorism financing, entail so many additional costs and risks that most international banks that deal in dollars won’t finance trade and investment in Myanmar, or allow U.S. companies to transfer profits back home.

Rose said he and his U.S. partners did not take earnings out of Myanmar, instead using the money to train local attorneys and staff.

It wasn’t supposed to be this difficult, especially for someone who built a career on shepherding Western companies to difficult places.

Born in communist Romania, Rose was a self-described student radical who moved to the United States in the 1970s and earned his law degree. He returned to Romania two decades later to help establish the first American law firm after the Iron Curtain fell.

He became a specialist in “frontier economies,” rough-and-tumble countries emerging from conflict, dictatorship and diplomatic isolation.

Working for American Standard, the venerable maker of plumbing fixtures, he traveled to Bulgaria, where his local partners employed leather-jacketed bodyguards strapped with machine guns. In Vietnam, negotiating to open the first U.S. factory since the end of the Vietnam War, he schmoozed with a top Communist Party official over glasses of rice wine mixed with serpent blood.

“I have done things in my life that may have been slightly crazy,” Rose said. “But I always believed in the purpose of what we were doing.”

I have done things in my life that may have been slightly crazy. But I always believed in the purpose of what we were doing.

— Eric Rose

Rose began exploring a venture in Myanmar — where he had helped American Standard sell sinks and faucets in the 1990s before U.S. sanctions were imposed — when the military freed Suu Kyi from house arrest in 2010.

With the New York firm of Herzfeld & Rubin as equal partners and a personal investment of $250,000, Rose set up shop in a tan-and-white condo building in Yangon, the commercial capital. He recruited senior Myanmar attorneys, including a former ethnic rebel, a lawyer who had defended Suu Kyi when she was a political prisoner and an advisor to the army-led party then ruling the country.

“It was an exciting time,” Rose recalled. “A number of U.S. sanctions had been suspended, there was a new can-do attitude in both the Myanmar and foreign business communities…. Myanmar was again on the move and we were the first American lawyers to try to help the country develop.”

The needs were immense. Myanmar had once been among the richest countries in Southeast Asia, but military rule had hollowed out its farm economy and education system. American companies saw opportunities in building roads, brewing beer, sourcing factory-made clothes, selling insurance and drilling for oil and natural gas.

From the start, the military-led government, unwilling to lose its monopolies in key industries, was slow to ease restrictions on foreign investment. Then the Treasury Department revised its sanctions rules, adding to the long list of Myanmar companies that U.S. companies couldn’t partner with.

One of Rose’s clients, Holloman Corp., a Houston oil and gas company, abandoned Myanmar and a $2-million initial investment in 2015 after becoming frustrated with the pace of change to investment laws, he said.

Optimism resurfaced the following year after Suu Kyi’s party took power and pledged to pump money into infrastructure and agriculture. But her government — largely made up of aging former activists and political prisoners with little administrative experience — failed to enact the changes that foreign companies wanted, including intellectual property protections and overhaul of a beleaguered court system.

A long-awaited corporate reform law, which would allow foreign investors to own up to a 35% stake in Myanmar companies, passed in December 2017 but is still months away from being implemented.

“Almost none of what they pledged has happened in the last two years,” Rose said. “There have even been some steps backward.”

Rose hosted dozens of small and midsize companies that were interested in Myanmar. But only about 1 in 6 established an office, he said.

In December, the German consultancy Roland Berger released a survey of Myanmar executives that found only 49% expected the business climate to improve over the next 12 months, down from 73% a year earlier.

The Rohingya crisis has clouded the investment picture further. The Trump administration has blacklisted the army general who it said commanded the offensive, and some in Congress are pushing for broader sanctions against Myanmar’s military.

A small group of shareholders in Chevron, which, along with Coca-Cola, is the largest U.S. company in Myanmar, has asked the oil giant to consider ending its involvement in a pipeline project and offshore gas fields because of the violence against the Rohingya. If the company rejects the request, shareholders could appeal the decision to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

In recent months, according to Western officials briefed on the decisions, the European Union suspended talks on an investment agreement with Myanmar over human rights concerns, and representatives of the U.S. insurer MetLife, which had been scouting Myanmar since 2013, gave up on plans to sell life insurance there because the Myanmar government had delayed lifting limits on foreign investment in the sector.

Some who dealt with Rose, who split his time between Yangon and Washington, said he didn’t fully understand Myanmar and tended to alienate people with a style that could be abrasive. Others said his relatively small office, with local lawyers who were more accustomed to political cases, lost out to multinational firms that came in after him.

“Myanmar is a really a hard place, and sometimes the first-mover advantage isn’t advantageous and you end up being the sacrificial lamb,” said Erin Murphy, founder of Washington-based Inle Advisory Group, which advises investors in Myanmar.

Rose’s office shrank from 15 employees to six, and his investment evaporated. In February, the firm closed the Yangon office, calling it “a necessary change of strategy in line with our priorities.”

Rose flew back to Washington, where he said he has new priorities of his own: his four grandchildren.

“I believe if you want to do something, you go in with both feet and stay as long as you possibly can,” he said. “In this case, it may have been a bridge too far.”

To read this article in Spanish click here

Shashank Bengali is the South Asia correspondent for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.