Back Story: India’s gay sex ban was a relic of the British Empire — but it’s still in place in dozens of ex-colonies

Reporting from Mumbai, India — When India’s Supreme Court this week legalized same-sex intercourse between consenting adults, it buried, most likely forever, a 157-year-old law introduced during British colonial rule.

The decision was a landmark — not least because civil rights activists hope it will galvanize the repeal of similar anti-gay legislation that remains on the books in dozens of other former outposts of the British Empire.

Britain decriminalized homosexuality beginning half a century ago, but the vestiges of its Victorian-era morality laws linger from Antigua to Zambia. About 35 members of the Commonwealth of Nations, made up mostly of former colonies, ban same-sex relations, accounting for roughly half the countries that outlaw gay intercourse.

This year British Prime Minister Theresa May said she deeply regretted “the legacy of discrimination, violence and even death” left by the legislation and pledged more than $7 million to support repeal efforts in Commonwealth countries.

The harshest anti-gay laws in the world, including some carrying the death penalty, exist in the Middle East and weren’t inherited from the British. But in many former colonies in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean, conservative political parties and religious groups have resisted efforts to repeal the old legislation. Here are some Commonwealth countries where the laws remain in force:

Malaysia

Malaysia’s law, like India’s, is listed under Section 377 of the penal code and bans intercourse “against the order of nature.” Conviction carries a punishment of five to 20 years in prison.

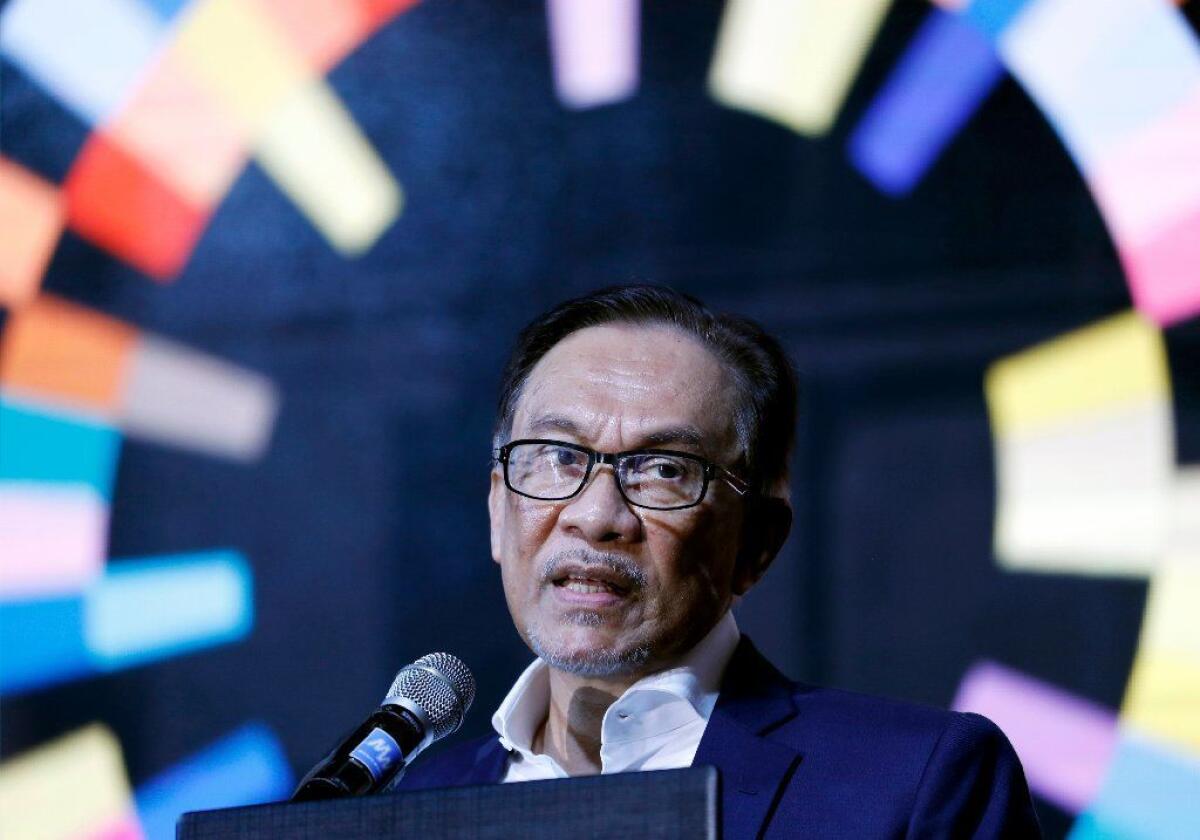

Previous governments used the statute to target Anwar Ibrahim, a longtime opposition leader, who was convicted and jailed twice on sodomy charges that many critics said were politically motivated.

In May, Anwar was released from prison before the end of his five-year sentence after the shocking election defeat of his nemesis, Prime Minister Najib Razak. The new leader, 93-year-old Mahathir Mohamad, who returns to the position he held from 1981 to 2003, struck a deal that allows Anwar to succeed him as prime minister.

But repeal of Section 377 is far from certain in a Muslim society often hostile to homosexuality.

Just this Monday, two women were publicly caned in the country’s northeast under provincial Islamic laws on allegations of having lesbian relations, reportedly the first time such a punishment had been implemented in the state for any crime. Mahathir said he opposed the sentence, saying it ran counter to the “compassion of Islam.”

Singapore

In Singapore, same-sex intercourse remains a crime, although the government has pledged not to harass gays. For the last decade, an annual “Pink Dot” rally drawing thousands of revelers has been held in the authoritarian city-state, where public gatherings are rare.

Foreigners were banned from attending the rally last year, in keeping with Singapore’s usually tight controls over freedom of assembly. The government told international companies such as Facebook, Google and Goldman Sachs that they could no longer sponsor the event because it related to “controversial social issues with political overtones.”

In a sign of domestic support for the LGBTQ community, dozens of Singaporean companies stepped in to sponsor the festivities.

Following the Indian ruling, Singapore’s law minister said a growing number of citizens were in favor of decriminalizing homosexuality but added that “the majority are opposed to any change.”

Brunei

Homosexuality has long been a criminal offense in the tiny oil-rich sultanate on the Southeast Asian island of Borneo. But in 2014, as part of an increasingly conservative turn under long-ruling Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah, Brunei introduced a new Islamic legal code that allows a punishment of stoning to death for a variety of offenses, including sodomy.

Human Rights Watch has denounced it as “medieval punishment.” Several Hollywood celebrities, including Ellen DeGeneres and Jay Leno, said they would boycott the Beverly Hills Hotel and other luxury properties owned by the sultan.

Malawi

Authorities in the southern African nation in 2012 said they would no longer enforce laws against same-sex intercourse. But occasional arrests have still been reported.

In April, police in the northern city of Mzuzu arrested a 24-year-old man “on suspicion that he is gay,” local media reported, even though being gay is not a crime.

Uganda

Authorities rarely prosecute Ugandans under the anti-gay statute, but have often used the law as a cover to clamp down on LGBTQ-related events.

Last December, police shut down the Queer Kampala International Film Festival in the capital city. That followed similar bans on events related to Pride Week and, in 2012, a human rights workshop led by LGBTQ activists.

Longtime President Yoweri Museveni is often dismissive of gays and gay rights, describing them as being imposed by the West and incompatible with African culture. Last month he told an audience: “You cannot stand up here and say, ‘I am a homosexual.’ People will not like it.”

Kenya

Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta has made similarly homophobic comments, telling CNN recently that gay rights were “of no importance to the people of Kenya.”

But the justice system has been more receptive. A case challenging the gay sex ban was heard in court this year, with a decision expected soon. Also this year, an appeals court outlawed the police practice of conducting rectal examinations of male prisoners suspected of engaging in homosexual sex.

The Caribbean

In 1991 the Bahamas became the first former British colony in the Americas to strike down its anti-sodomy law, but 25 years would pass before the Central American nation of Belize became the next.

This year, a court in Trinidad and Tobago ruled that its British-era laws prohibiting “buggery” and indecency were unconstitutional. The plaintiff in the case, Jason Jones, an openly gay activist who fled Trinidad because of discrimination, said that after he brought the lawsuit he received hundreds of death threats and hate messages.

In seven former island colonies in the eastern Caribbean — including Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados and Grenada — similar laws remain in force. According to Human Rights Watch, while few people have faced criminal prosecutions, the laws “give social and legal sanction for discrimination, violence, stigma, and prejudice against LGBT individuals.”

The rights group said that the Trinidad ruling, which found that all citizens were entitled to the same constitutional rights, could reverberate in other Caribbean nations with similar statutes.

Special correspondent Roughneen reported from Bangkok and Times staff writer Bengali from Mumbai.

Shashank Bengali is South Asia correspondent for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.