How famously uptight Singapore became a playground for Asia’s ‘crazy rich’

Reporting from Singapore — While movie audiences worldwide relish the million-dollar earrings and private jets of “Crazy Rich Asians,” Singaporeans would like you to know that in reality, things here can get even richer and even crazier.

One described a wedding reception where Diana Ross performed. Another told of a son from a wealthy family who knocked out his front teeth chugging from a magnum bottle of Dom Perignon.

An heir to a business fortune admitted — no, more like bragged — to a newspaper that he’d once walked into a designer shoe store and said: “I’ll take one pair of everything you have, in every color.”

“The movie is just a really nice romantic comedy,” said Juliana Chan, a scientist and magazine editor. “It didn’t feel over-the-top.”

The real-life stories of Singapore’s ultra-rich illustrate this tiny city-state’s remarkable transformation from a sleepy colonial trading post with no natural resources into a global financial capital and playground for the 1%.

But the tales of excess hardly square with the obsessively disciplined, authoritarian ethos that propelled the island to prosperity over the last half-century. Even as many Singaporeans revel in Hollywood’s sumptuous portrayal, “Crazy Rich Asians” has renewed questions about inequality and privilege in a society that was founded on values of hard work, equal opportunity and social order.

“The movie has lit a spark because it seems to be celebrating wealth that 99% of the country can’t access,” said Aun Koh, an entrepreneur. “And in the last 10 years that gap has gotten worse.”

The signs of Singapore’s success are everywhere — the Instagram-ready pool parties atop five-star hotels, the designer boutiques shimmering along tree-lined boulevards, the oceanfront mansions on the resort island that hosted President Trump’s summit in June with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

One out of every 34 Singaporeans is a millionaire, the highest density of any Asian city, according to the research company WealthInsight. With a population of about 5.5 million, Singapore has a $57,000 per capita income — nearly that of the United States.

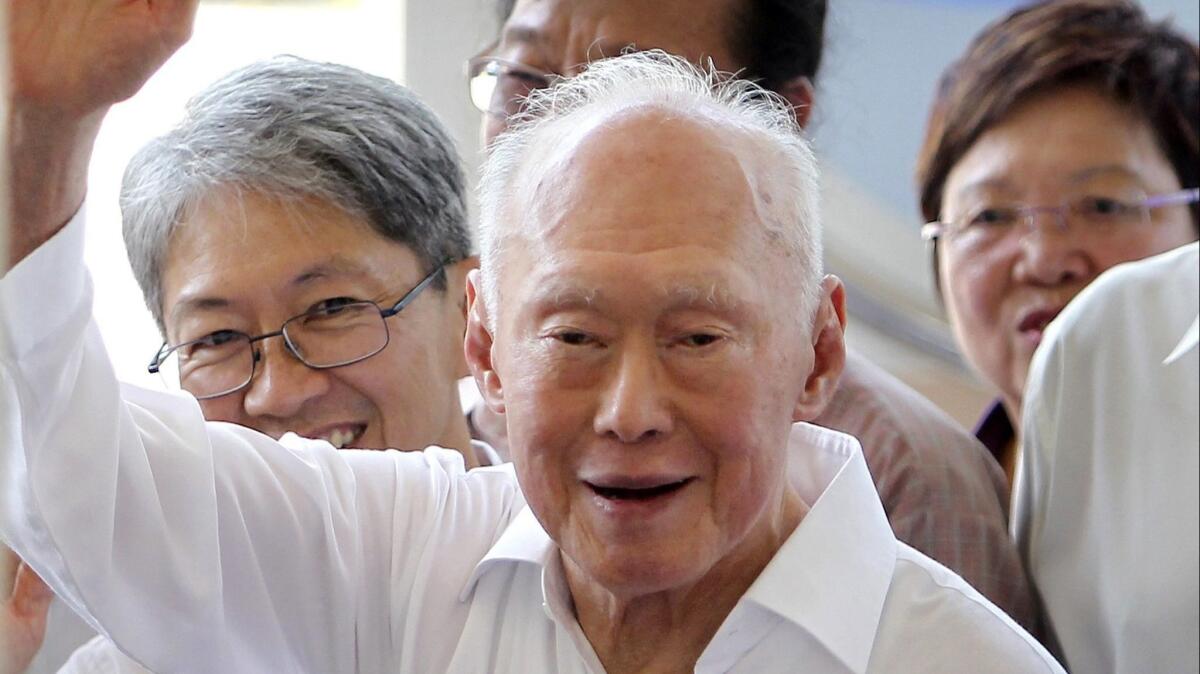

It got this way under the guidance of the late Lee Kuan Yew, who was prime minister when the former British colony separated from Malaysia and became independent in 1965. Lee built a ruthlessly efficient government that paid handsome salaries to recruit top-notch Cabinet ministers and drew investors from around the world to the island’s strategic location along one of the world’s busiest shipping corridors.

Disdainful of democracy and famously abstemious — he reportedly wore the same exercise shorts for 17 years — Lee led a one-party state that enforced strict notions of public behavior. Graffiti, feeding pigeons and the sale of chewing gum were banned.

But he also created an enviable system of schools, hospitals and public housing that was meant to guarantee everyone in the multiethnic country — mainly Chinese, but with sizable groups of Indians and Malay — an equal chance at success.

Singapore was to be a meritocracy, in Lee’s vision, and those who succeed shouldn’t flaunt their advantages. His son, current Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, said recently that Singaporeans “should frown upon those who go for ostentatious displays of wealth and status, or worse, look down on others less well off and privileged.”

But the younger Lee earns more than $1.7 million. And last month, just before “Crazy Rich Asians” premiered in Singapore, a controversial comment by former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong laid bare a growing social divide.

Goh was asked whether government ministers’ million-dollar salaries should be reduced to increase entitlements for the elderly. Rejecting the idea, he said that in that case the government would only be able to attract “very, very mediocre people who can’t even earn a million” Singaporean dollars, or about $730,000, in the private sector.

Many Singaporeans were appalled.

“What was worse is that not a single political leader spoke up to criticize the comment,” Koh said. “There’s a huge problem if this whole layer of government has this snobbish attitude….

“There’s a lot of resentment building up, and the movie didn’t do any favors to the people in authority.”

Even the vaunted public schools, long the pathway for working-class students into top business and government jobs, are becoming more stratified as generations go on. The best high schools award some spots to the sons and daughters of alumni and others to those who live in surrounding neighborhoods — where housing prices have naturally soared into the millions of dollars.

The principal of one of the top schools, Raffles Institution, which counts Lee Kuan Yew and many Cabinet members as alumni, recently said he was struggling to recruit students from diverse backgrounds because some were worried about not fitting in with wealthier classmates.

“The divide is entrenched very early in life,” said Chan, the scientist and magazine editor.

Some experts say the very policies that have made Singapore an attractive investment destination — low corporate and personal income tax rates, and no capital gains or estate tax — have made it more unequal.

Chinese businessmen have flocked to the island since 2008, bringing a flood of new money and gaudy spending that Singapore’s original ethnic Chinese business families — like the relatively low-key Young clan at the center of “Crazy Rich Asians” — regard as gauche.

But the government has courted the new arrivals with tax breaks and other inducements — including building two luxurious casinos despite Lee Kuan Yew’s longtime opposition to gambling. At the casino at the Marina Bay Sands hotel complex — the three curved towers topped by a ship-like terrace — Singaporeans must pay a $70 entry fee while admission is free to foreigners.

“The red carpet is rolled out for foreigners, especially the wealthy,” said Linda Lim, a Singapore-born professor of international business at the University of Michigan.

“The whole society is now based on making money…. It is at odds with our founding values.”

Still, many Singaporeans see inequality as the cost of a relentlessly capitalistic system that rewards certain types of skills. In official terms, Singapore has no poverty — because it has not defined a poverty line — and no pension system, in keeping with the founding ethos that everyone must work.

Many struggling elderly Singaporeans, often without families to support them, bus tables at the city’s ubiquitous outdoor food stalls or collect cardboard boxes to recycle for money.

“We accept some inequality in order that we can have the kind of economic prosperity that has brought us this far,” said Irene Ng Yue Hoong, an associate professor of social work at the National University of Singapore.

But the government has been sensitive to criticism over inequality and responded with additional subsidies — expanding access to early childhood education for low-income families and announcing welfare packages for seniors born in the 1940s and 1950s, before the economic boom.

“The need to maintain upward mobility is really important for the government’s legitimacy,” said sociologist Chua Beng Huat. “But the government’s idea is to keep raising the bottom of the economic ladder, rather than restrict the top.”

Twitter: @SBengali

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.