In the Philippines, the Marcos name is back, even as memories of the dictator have faded

Reporting from Manila — In the Philippines, the Marcos name is back in vogue.

For two decades, the dictator Ferdinand Marcos pilfered billions from the country’s public coffers; his government reportedly tortured opponents by shocking them with live wires and burning them with irons. After his ouster in 1986, his legacy was so toxic that then-President Corazon Aquino established an office— the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) — to “restore the institution’s integrity and credibility,” according to its website.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

May 7, 6:23 p.m.: An earlier version of this post referred to Ferdinand Marcos’ three children. He was the father of four.

------------

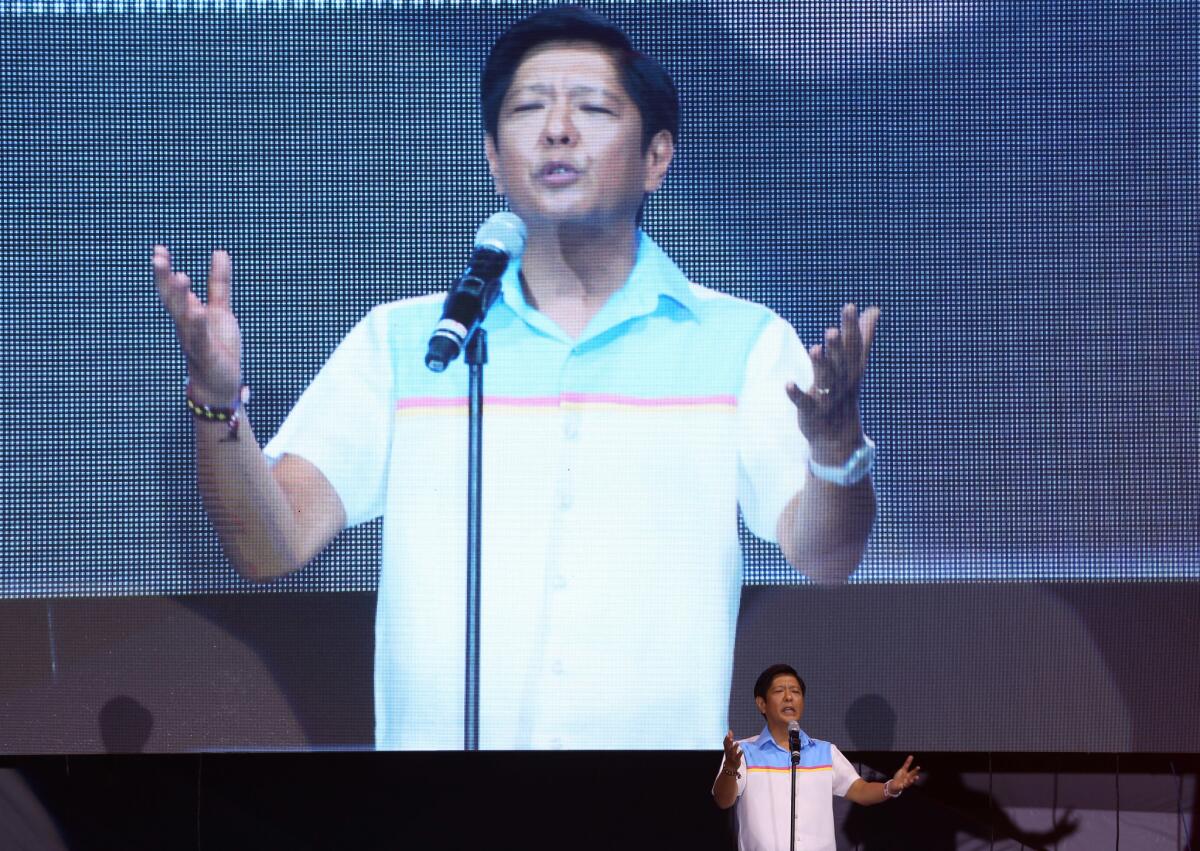

Yet memories of the dictatorship’s brutality have begun to fade, even as the country’s next presidential elections, scheduled for May 9, have brought his name back into the spotlight. Marcos’ son Ferdinand Marcos Jr., known by his nickname “Bongbong,” is leading opinion polls in the vice presidential race. (In the Philippines, the president and vice president are elected separately.)

Many Filipinos believe the country needs a strong, no-nonsense leader to help overcome its struggles with corruption, poverty, drugs and crime.

Ronald Chua, a PCGG commissioner, ascribed Marcos Jr.’s popularity to young Filipinos who did not experience life under his father’s rule.

“To be honest, millennials, they don’t have any idea of what happened in the ‘60s and ‘70s,” he said. “What they know is only what they read in the books, and it’s just not enough information — what you can read in the textbooks now is, I would say, just 1% of what happened during the time.”

How a Marcos Jr. vice presidency would coexist with the commission remains an open question. The organization is not partisan, Chua said, but if Marcos is elected, “it will be harder for the office to perform its function.”

Over the past six years, under President Benigno Aquino III, the Philippines’ annual economic growth rate has been above 6%, ranking the country among the world’s fastest-growing economies. Yet more than a quarter of Filipinos remain impoverished, and the extreme gap between rich and poor weighs heavy in the minds of citizens.

Rodrigo Duterte, a 71-year-old city mayor and self-styled strongman, is leading in the presidential polls.

“People who are supporting Bongbong Marcos are the same people who are favorably inclined toward Duterte,” said Gerard Finin, director and senior research fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu. “These are people who think strong leadership is necessary regardless of rule of law. I don’t think that’s a majority by any means, but there are people who have forgotten the position martial law left the Philippines in, in terms of human rights, the economy — all the things that have taken decades to rebuild.”

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

According to Amnesty International, the Ferdinand Marcos government imprisoned 70,000 people, tortured 34,000, and killed 3,240. During his tenure, the Philippines’ national debt exploded from $2 billion to as high as $30 billion, while his family and close associates grew scandalously wealthy. His wife, Imelda Marcos, famously owned more than 1,000 pairs of shoes. He was unseated by a bloodless “people power” revolution in 1986 and fled to Hawaii, where his family lived in exile; he died three years later.

And although Marcos Jr. — one of the dictator’s four children — has distanced himself from his father’s legacy of brutality, critics say that he has refused to address it head-on.

Marcos Jr.’s supporters “think that he is being blamed for his fathers sins,” said Solita Monsod, a professor emeritus at University of the Philippines School of Economics. “He is not being blamed – he is blamed for not saying that his father has sinned. He thinks his father did everything right – that [his] age was a golden age.”

The Marcos campaign did not respond to several requests for comment.

Bongbong Marcos grew up in the Philippines, and was sent to England in 1970 while his father was at the height of his power. He studied social studies at Oxford University, and then business at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, but dropped out in 1980 after he was elected the vice governor of the Philippines’ Ilocos Norte province, where his father was born. He was 23 years old, and his political party — Kilusang Bagong Lipunan — was the same as his father’s.

In 1983, Marcos Jr. rose to become the province’s governor; his term ended prematurely in 1986, after his father’s ouster. He returned to the Philippines in 1992, and refers to his time overseas as an “enforced vacation.”

“I did not want to do the same things [that] my father [did],” Marcos told the Philippine Daily Inquirer in late April. “I told myself that everything anyone can possibly do in politics, my father had already done. He was president and had a very noteworthy presidency.”

“To tell you the truth, he was just Dad,” he continued, “But, of course, you knew he was a different person because when he walked into a room, the room stops and everybody would defer to him. He was in control. He was the boss.”

His mother, Imelda Marcos, is currently a member of Congress; his sister Imee is the governor of Ilocos Norte.

The PCGG is a small operation — it currently has only three commissioners and about 100 staffers — but as of December, it had recovered about $3.6 billion of the Marcos dictatorship’s ill-gotten gains, some of it from accounts in Switzerland. It has organized several educational events at universities to promote awareness of Marcos Sr.’s massive plunder of the country’s wealth.

The organization is working to recover more than 200 of Marcos’ paintings, including works by Michelangelo, Monet, Rembrandt, Picasso and Van Gogh. The collection is estimated to be worth between $150 million and $300 million. Only about 14 works have been found.

Alex Magno, a political science professor at University of the Philippines and columnist for the Philippine Star, questioned the organization’s future prospects. “The cost of maintaining [the commission] does not justify it existing,” he said. “So if there is a head-on [conflict] between Marcos and the PCGG, the PCGG folds.”

“They have gotten what they could,” he continued. “The rest will take a few centuries of litigation. The cost of litigation is not commensurate to the amount of wealth they can possibly retrieve.”

The current President Aquino — the son of Corazon Aquino, who established the commission — has been one of Marcos Jr.’s most strident critics. (His preferred vice presidential candidate, Manuel “Mar” Roxas II, has consistently lagged in the polls.)

“The blood relatives of the dictator could have said, ‘My father was wrong, give us a chance to correct this,’” Aquino said in February, on the 30th anniversary of Marcos Sr.’s ouster. “If he can’t see what his family did wrong, how will we know that it won’t happen again?”

De Leon is a special correspondent. Staff writer Julie Makinen contributed to this report.

Follow @JRKaiman on Twitter for news from Asia

ALSO

This is how serious India’s drought has gotten

Kim Jong Un, hailing hydrogen bomb test and satellite launch, predicts ‘final victory’

Inside North Korea’s Children’s Palace, a reporter finds children turning into robotic grown-ups

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.