NEBAJ, Guatemala — Gabriel de Paz still dreams that he’s running from the dictator’s soldiers.

When the military invaded his Guatemalan mountain town in the early 1980s, De Paz and his Maya family abandoned their animals and their straw-roofed home and fled into the woods. They hid as Gen. Efraín Ríos Montt’s security forces burned villages and massacred Indigenous civilians they suspected of collaborating with leftist guerrillas.

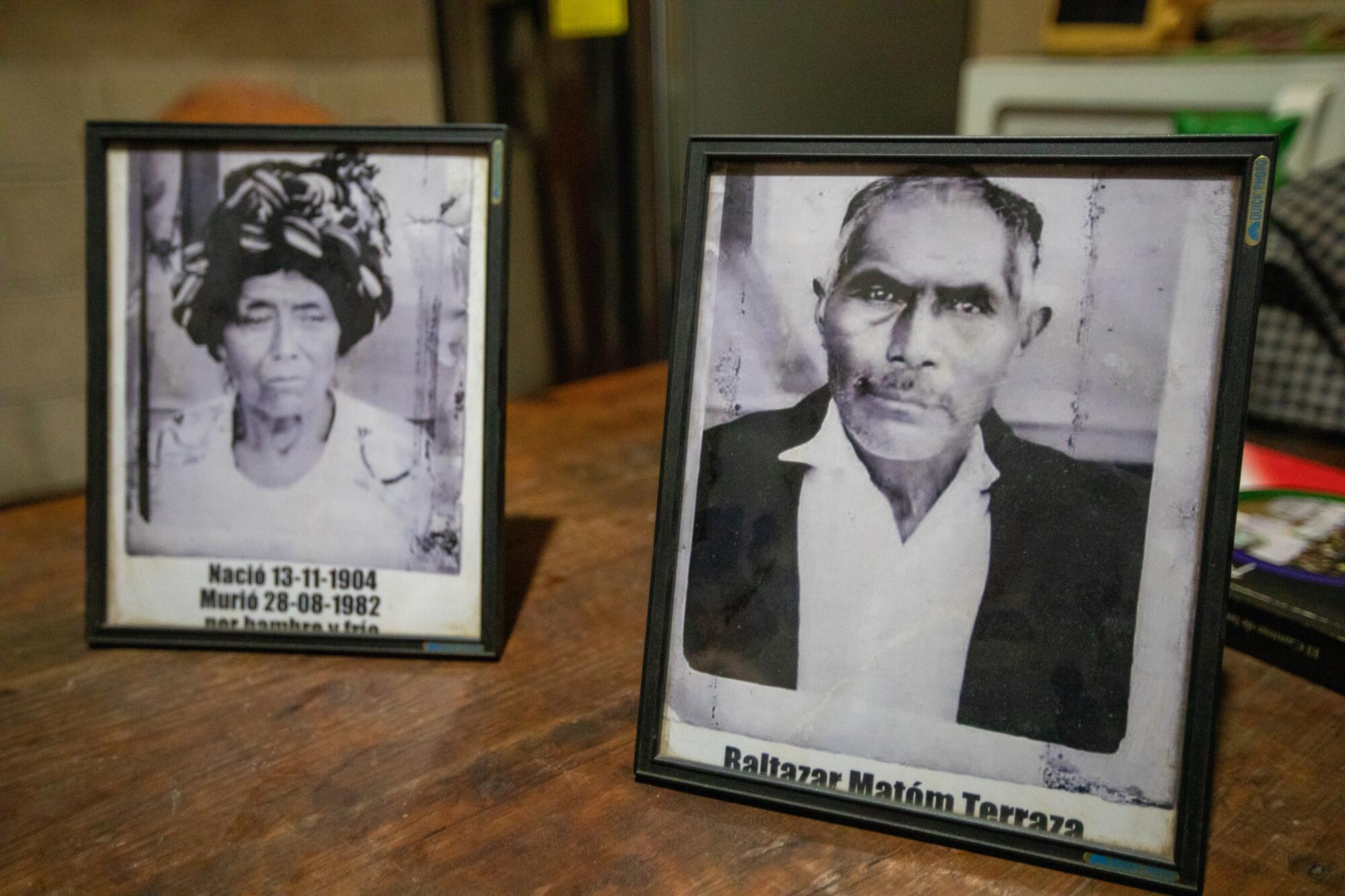

To De Paz, the general is why his family spent years in hiding, why his grandmother starved to death, why he still has nightmares.

The farmer imagined that his people’s memories of the mass killings under Ríos Montt remained vivid, passed through generations.

Then the dictator’s daughter came to the mountainous Ixil region this spring to launch her presidential campaign.

De Paz was dumbfounded. Zury Ríos received a warm welcome from hundreds wearing the traditional embroidered blouses and straw hats of the Maya Ixil.

Here was the strongman’s daughter standing next to an Ixil interpreter and speaking about how villagers needed agricultural fertilizers and schools with running water. People were cheering.

“There are a lot of youth but there are also grandparents who remember the hard times we lived, and that’s why forgiving is so necessary, that’s why reconciliation is so necessary,” she told the crowd.

That was as close as she came to talking about what courts have deemed a genocide but that in interviews she denies ever took place.

De Paz, 62, doesn’t see an attempt at reconciliation, only an effort to expunge a traumatic history.

“They want to erase, they want to cancel,” he said, sitting at his kitchen table in Nebaj, a municipality in the Ixil highlands. “That’s our worry if she governs.”

Guatemala has long fought over how its darkest chapter should be remembered, with Indigenous and human rights groups accusing right-wing forces of using their political power to bury the past.

The government has stopped providing survivors reparations, and the 36-year civil war, which claimed more than 200,000 lives, is barely taught in public schools, activists say. Prosecutions of ex-military officials have run up against the erosion of the judiciary’s independence.

Ríos’ run raises questions about a country’s collective memory: How much should a nation strive to remember its traumatic past? What happens when it forgets?

Ríos, 55, carries her father’s name and his fierce stare. She’s tried to burnish his legacy, and she’s not alone.

Military families and right-wing power brokers have long said that both sides in the civil war committed excesses, and some have portrayed Ríos Montt as a hero who had saved the country from guerrillas.

They have disputed the findings of a truth commission — created as part of the United Nations-backed 1996 peace accords — that said security forces committed more than 90% of documented human rights violations. The government had exaggerated Maya support for the guerrillas, resulting in indiscriminate violence toward them and “acts of genocide,” the commission found.

The country descended into civil war not long after a CIA-backed coup in 1954 toppled Guatemala’s elected president whose agrarian reforms had alarmed the U.S.-owned United Fruit Co. That gave rise to a series of military governments and the leftist rebels who organized to fight them.

Ríos Montt, brought into power by one coup and removed by another, ruled atop a military junta in 1982 and 1983, considered among the most deadly years of the civil war.

In 2013, the general was found guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 80 years in prison for massacres in Ixil villages that killed more than 1,770 people. His conviction was overturned on procedural issues, and he died in 2018 during his retrial.

In an interview, Ríos said her father’s trial had been unfair. She had started her political career alongside him, getting elected to Congress in her late 20s and serving four terms as part of his right-wing party, where she focused on women’s and healthcare issues. She’s in a different party now but is backed by military families who share her views of the civil war.

One influential supporter, Ricardo Méndez Ruiz, is the son of a military commander who served as interior minister under Ríos Montt. Méndez Ruiz has called the former dictator “the best president Guatemala has had in modern times.”

Méndez Ruiz, who has been sanctioned by the U.S. State Department for attempting to obstruct criminal proceedings against former military officers, touts on his Twitter bio his inclusion on the agency’s “corrupt and undemocratic actors” list. The group he co-established and runs, the Foundation Against Terrorism, has filed criminal complaints to target judges and prosecutors who have worked on corruption and war crimes cases.

Méndez Ruiz said he expected Ríos would push for an amnesty law “to end the persecution of our war veterans.”

Ríos’ campaign filmmaker, Kenneth Müller, is also the son of a former military man, a retired colonel. Müller, who directed a film based on a 1980 bomb attack in Guatemala City attributed to a guerrilla group, contends “Guatemala is victim of a lie.” After the peace accords, he said, “all the military returned home but the left didn’t, they dedicated themselves to write stories and create a narrative.”

But the narrative of the right has consistently found a place in politics.

The bloodshed of Ríos Montt’s military rule didn’t stop him from reentering political life. He served several terms in the legislature, at several points becoming head of Congress, and ran unsuccessfully for president. He lost immunity from prosecution when his last term ended in 2012.

More recently, members of Congress — including from Ríos’ Valor party — have tried repeatedly to pass an amnesty law that would free convicted war criminals.

Though ex-military officials have been convicted and prosecutions against others continue, human rights groups say they face increasing challenges as democracy backslides in Guatemala. In recent administrations, the government expelled a United Nations-backed anti-corruption commission, and prosecutors and judges have fled over intimidation.

The government has dismantled peace institutions that served survivors of the civil war. A 2003 program to provide victims with therapy and economic reparations hasn’t offered relief to families since President Alejandro Giammattei took office in January 2020, according to Miguel Itzep, a leader of an Indigenous-directed national victims association.

And as the decades tick by and survivors age, human rights groups say many schools aren’t ensuring students know about the bloodshed. Public school curricula mention the civil war, but rights groups note educators aren’t encouraged to teach it.

Vivian Salazar Monzón, director of the Guatemalan International Institute of Learning for Social Reconciliation, said the Education Ministry has stopped engaging in efforts to teach human rights and the civil war.

“What this has cost Guatemala is that we have citizens that don’t know their past,” she said.

Neither the Education Ministry nor the Ministry of Social Development, which oversees the reparations program, responded to requests for comment.

Recent attacks on Judge Miguel Ángel Gálvez are part of a broader campaign on Guatemala’s courts that have forced nearly two dozen judges and prosecutors into exile.

“It’s an issue of citizen conscience,” Salazar continued. “We are forming people who don’t know the responsibility and role of the state, who vote blind, who aren’t thinking about the consequences of authoritarianism.”

When asked whether schools are doing enough to teach the civil war, Ríos pivoted repeatedly, including to say that students should participate in activities that “foster peace,” such as music, art and sports.

“Wars are wars and they leave tragedy, no one wins and no one loses,” she said. “Everyone suffers, but you go on, you advance, you progress.”

In any case, she said, “the person who is running for president is me, not Gen. Ríos Montt.”

On a recent Sunday morning, Ríos held a microphone, eyes focused on the sun-baked crowd in front of her, as she shared a stage with a congressional and mayoral candidate in Rio Bravo, a non-Maya municipality in the southern flatlands a few hours outside Guatemala City. As several hundred people sweated in their campaign T-shirts, she noted that the taxes on every pound of beans they buy help pay the salaries of local officials who have failed to build a new hospital or fix a bridge.

“It hurts me, it hurts me when I see here many of the most needy, the most forgotten, who vote every four years and their lives don’t change,” she told the crowd, her voice cracking.

In a country where more than half of the population lives in poverty and many migrate to search for better opportunities in the United States, Ríos campaigns on tackling inequality with broader internet coverage, mental health services in schools and mobile medical clinics in poor communities.

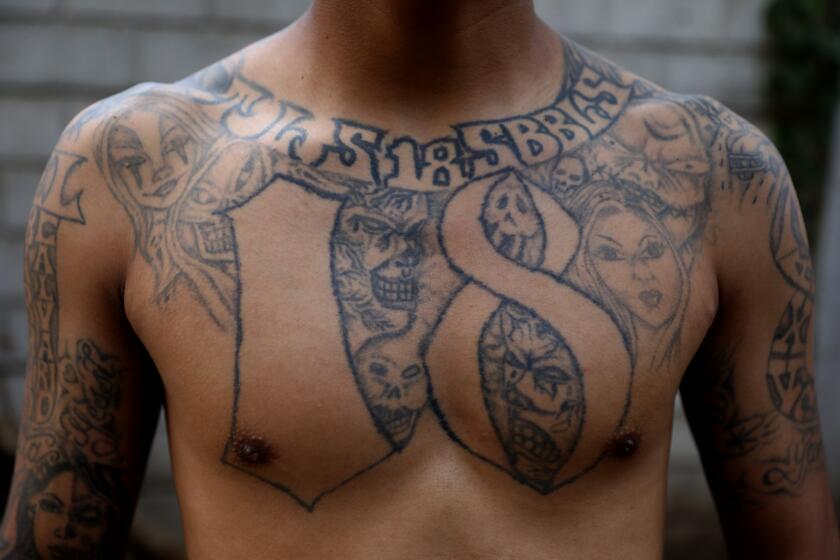

El Salvador’s evangelical churches rehabilitated ex-gang members. The country’s crackdown on L.A.-born gangs like MS-13 emptied programs and filled prisons.

She’s also praised the controversial gang crackdown in neighboring El Salvador, which has conducted widespread arbitrary arrests to reduce homicides, according to human rights groups.

Ríos ran unsuccessfully for president in 2015 but was blocked in 2019 after the country’s electoral tribunal ruled the constitution prohibits children of coup leaders from becoming president. This time, the country’s Constitutional Court allowed her on the ballot for the conservative Valor-Unionista coalition.

Courts have blocked several others, including the leftist Indigenous candidate Thelma Cabrera and the popular political outsider businessman Carlos Pineda.

If no candidate gets more than 50% of the vote in the June 25 election, the race to succeed Giammattei will go to an August runoff. Recent polls have placed Ríos among the top three candidates, along with former First Lady Sandra Torres and longtime diplomat Edmond Mulet.

Laura Hernández, 44, came to the Rio Bravo rally to support the mayoral candidate but liked the idea of a female presidential hopeful. She and several others couldn’t recall much about Ríos’ father or the civil war.

“It was a good government, prices were very low, as well as crime,” she said her own father had told her.

At a campaign stop that night in the municipality of Mixco — which drew voters with a fireworks display — residents seemed more concerned about unreliable access to water than the background of politicians.

Janneth Tema, 32, said she liked Ríos’ calls for tougher security measures and her support for the elderly. And she found it natural for the candidate to defend her father.

“She’s unfortunately chased by the shadow of her father,” she said.

Tema’s mother, Claudia, said that Ríos Montt “has nothing to do” with his daughter’s candidacy and that she doesn’t think Ríos will commit the “errors he made.”

The elementary school teacher said that she has taught the civil war in school, but that some of her colleagues worry about upsetting parents.

“I have colleagues that teach it, but it’s the minimum,” she said.

Her daughter Lesly Tema, 30, made a blank face when asked about the civil war and Ríos Montt.

“I don’t remember a lot,” she said.

A six-hour drive from Guatemala City, up the winding mountain roads leading to the Maya Ixil region, the memory of Ríos’ father is still strong for many.

In this hill country where women make and wear embroidered traditional blouses called huipiles and long skirts in colors marking their towns, many of the more than 150,000 residents scratch out a living growing beans and corn. Few of the tin-roofed homes have basic appliances such as an electric stove or a refrigerator. Teenagers sometimes leave their towns before they’ve finished high school to migrate to the U.S. to send back remittances.

It’s a place that’s slowly recovering Maya traditions that were lost in the violence under Ríos Montt, which displaced tens of thousands. Ixil ceremonies, such as to ask for rain or to apologize to a mountain for using its land, are becoming more common. It’s taken years to reestablish Indigenous councils that take up issues such as domestic violence or land disputes.

In May, on Mother’s Day, several hundred locals participated in a bus caravan that stopped at the main squares of the region’s three municipalities to mark the 10th anniversary of Ríos Montt’s genocide conviction.

A car crawled through narrow streets, a poster on its front bumper declaring “There was genocide.” Passersby walked on as a boom box tied to the car’s roof repeatedly blared the words “The Ixil people do remember” and played the judge’s genocide verdict. In the squares, speeches rang out in Ixil and Spanish.

“Think about your vote,” a man said into a microphone at one stop. “Zury Ríos of the Valor party is [from] a party of death, a party of revenge, and the Ixil people won’t accept it.”

On one of the buses, Elena de Paz, a 52-year-old survivor, scrolled on her phone through Mother’s Day videos posted on Facebook and thought about whom and what she lost in the war.

She said that when she was 12, she watched helplessly as security forces sexually abused her mother, Jacinta, at a military base in Nebaj. As the child cried, someone stuffed a rag in her mouth; Elena was stabbed in the thigh and raped.

She never saw her mother again.

“Surely my mother isn’t buried,” she said matter-of-factly. “Perhaps they only threw her somewhere. We don’t know anymore.”

Having testified about the attacks at Ríos Montt’s trial, she said she would not vote for Ríos, who “has the same head as her father.”

Yet the Ixil people are divided about the presidential candidate — tensions partly tied to the military’s strategy during the civil war.

Many Ixil were forced to join paramilitary groups fighting the guerrillas to avoid being targeted themselves — often pitting them against their own people.

Ríos Montt offered the impoverished Ixil people food in exchange for supporting his rule and threatened those who refused. New “model villages” under rigid military control promised social services to the displaced and isolated them from the guerrillas.

Maya Ixil survivors of the violence during the civil war show the work they created during a therapy session to describe the pain they still feel. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

The aid and the divisions he created help explain why Ríos Montt’s party did unexpectedly well in the Ixil region when he returned to politics.

That support, in some cases, has passed on to his daughter.

“There are people in parts of rural Guatemala that look at her, and because of her connections to her father, they think of the heavy-handed mano dura policies to deal with the guerrilla movement, and that’s appealing to some people,” said Jo-Marie Burt, a Guatemala expert at the Washington Office on Latin America.

Today, Zury Ríos’ political party signs hang from electricity poles and dot the mountain roads where small, three-wheeled “tuk tuks” drive.

Jacinto Sambrano, mayor of the Ixil region’s Cotzal municipality and a member of Ríos’ Valor party, grew up in the 1980s in a “model village” that his father occasionally helped patrol. He denied that Ríos Montt oversaw a genocide and said the general protected the Ixil people during the war.

Sambrano claimed, without offering evidence, that the anniversary caravan was filled with relatives of guerrillas and that efforts to change the historical narrative are financed by leftist countries such as Cuba and Nicaragua.

“Ríos Montt is dead,” he said. “They signed the peace accords. Why do they want to revive something that has already passed?”

Others say residents are swayed by vote-buying practices, and lack education about political candidates and parties. Many of the elderly are illiterate, and speak only Ixil or little Spanish.

Engracia Reina Mendoza Caba, 49, a survivor and member of an Indigenous council for the Ixil municipality of Chajul, said Ríos came to the area for her campaign opener “without fear, without security, because she thinks all of Chajul supports her.”

Mendoza has tried to explain to townspeople that the candidate is the daughter of a man tried for genocide.

“Our own Ixil people don’t understand what happened here,” she said.

Parts of the past are still buried deep in the ground. But as the bodies of victims are exhumed, awareness grows.

The nonprofit Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation has exhumed more than 8,200 bodies in communities and at military bases and identified nearly 4,000 since 1992, said its director, Fredy Peccerelli.

Its DNA bank, created in 2008, has samples from about 17,000 relatives of the disappeared that it can compare with exhumed bone fragments. It receives no financial support from Guatemala’s government.

“The problem is that many people are dying without knowing the truth, without understanding what happened,” Peccerelli said. “They’ve spent their entire lives, 40 years, looking.”

Only after the bodies of Teresa López’s brother and sister were exhumed did she begin to tell her children about how their relatives died.

Catarina, 17, was killed by bomb shrapnel while she hid in a trench the family had dug. Domingo, 19, was killed by guerrillas after he was falsely accused of stealing food. The two are now in a cemetery in Nebaj. A third sibling, Diego, 25, was killed by soldiers and dismembered, said López, who saw his body. She doesn’t know where he is.

Her daughter, 28-year-old Nebaj resident Victoria Chel, plans to tell her 7- and 3-year-old children her mother’s story one day.

“They shouldn’t say we didn’t have a lot of family,” she said. “We had family, but the war took them.”

Others are searching for justice.

The day after the anniversary event, about a dozen survivors gathered in a church with a psychologist and others from the Human Rights Office of the Archbishop of Guatemala.

They were preparing to testify in next year’s trial of two former military officials accused of genocide against the Maya Ixil during the government that preceded the rule of Ríos Montt. A representative of the rights office told the group that they needed to be emotionally ready for aggressive questions that could trigger trauma.

The survivors worked with clay. One woman, Maria Garcia, molded a black flower and explained she was happy at seeing the support in the room but weighed down by more complicated feelings.

Her mother had attended survivor meetings, planning to testify about the murder of her husband. She died last year, and Garcia was taking her place.

At his home in Nebaj, Gabriel de Paz pulled artifacts from a large plastic bin.

Cassette tapes hold the interviews he conducted with other survivors and translated from Ixil to written Spanish for attorneys. Videos show survivors meeting to discuss how to recover land seized during the war. A book contains his testimony and that of other witnesses from the Ríos Montt trial.

De Paz spilled the contents of a green urn onto his kitchen table, running his hand through dirt mixed with ashen clumps of burned corn, unleashing memories from decades ago.

He was in Nebaj one day in 1982 when he spotted pillars of smoke rising from a nearby community. Security forces had gathered the area’s entire harvest of corn and piled the corn sacks in a huge volcano-like mound. They lighted it on fire.

Years later, De Paz attended a ceremony in the village of Xoloche where residents gather annually to mark the incident. The charred corn was still there.

“What fault does the corn have?” he thought angrily at the time. With a few others, he collected bits of the corn in some leaves.

A memorial plaque in Xoloche explains that the fire left the townspeople without food, and that a woman was thrown onto the blaze.

It also carries a clear message: “We don’t want this to repeat.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.