BUCKS COUNTY, Pa. — Bill Baird has been called many things: butcher, murderer, pied piper of sex, unholy deviant. It’s hard to imagine the 92-year-old man on the white couch once evoked so much wrath. But it was a dangerous time when Baird — who was shot at and punched, who lost his family and was jailed — won a 1972 Supreme Court decision that legalized contraception for unmarried women, earning him the nickname the “father” of birth control.

The privacy issues raised in Eisenstadt vs. Baird were cited less than a year later when the court voted to protect a woman’s right to abortion in Roe vs. Wade. Baird was elated but prescient about what was to come. He knew the persuasions of preachers and the power of the Bible to provoke America’s morality police. He warned a complacent abortion rights movement that the victory was in danger from a well-organized Christian right that would galvanize the Republican Party.

In 1980, he appeared like a party-crashing, secular prophet at a Dallas religious convention where televangelist Jerry Falwell and other right-wing pastors were mobilizing Christian voters and calling for Supreme Court justices to oppose abortion: “This is the first time in the history of this great nation of ours,” Baird said at the time, “that any single group has tried to seize control of the U.S. Supreme Court to force a particular religious viewpoint.”

And he says it’s happening again.

“No one listened. Look at today,” said Baird, sitting in a sunroom in a house in the green hills north of Philadelphia. “We’re going to head into a civil war. They [evangelicals] believe this ‘orange Jesus’ — this Trump — has special powers from God. I saw it developing back then. I knew it was coming. I’m still fighting it. This is the worst Supreme Court I’ve ever seen.”

Baird once frequented national talk shows, commanded handsome speaking fees and had a folk song written about him. These days, he’s an aging activist with scrapbooks, memories and a dog sleeping at his feet, an iconoclast in a suburb of mowed lawns and fine houses, who, unbeknownst to his neighbors, handed out contraceptives to single coeds and poor women in the 1960s and became a consequential figure in ensuring that women had control over their bodies.

Baird’s Supreme Court case “expanded the ability of unmarried women to take care of themselves and that right has expanded to other realms,” said Judy Waxman, former vice president of health and reproductive rights at the National Women’s Law Center. “It is about equal protection. That case is so relevant to this moment in history. I wouldn’t be surprised if it comes up again.”

But Baird was often vilified by some in the women’s movement as an interloper with a flair for bombast and sound bites who wanted to overshadow their cause. Betty Friedan, the author of “The Feminine Mystique,” and a founder of the National Organization for Women, wrongly disparaged him as a CIA agent. Planned Parenthood called his protest style an embarrassment. One feminist labeled him a pervert; another threatened to castrate him.

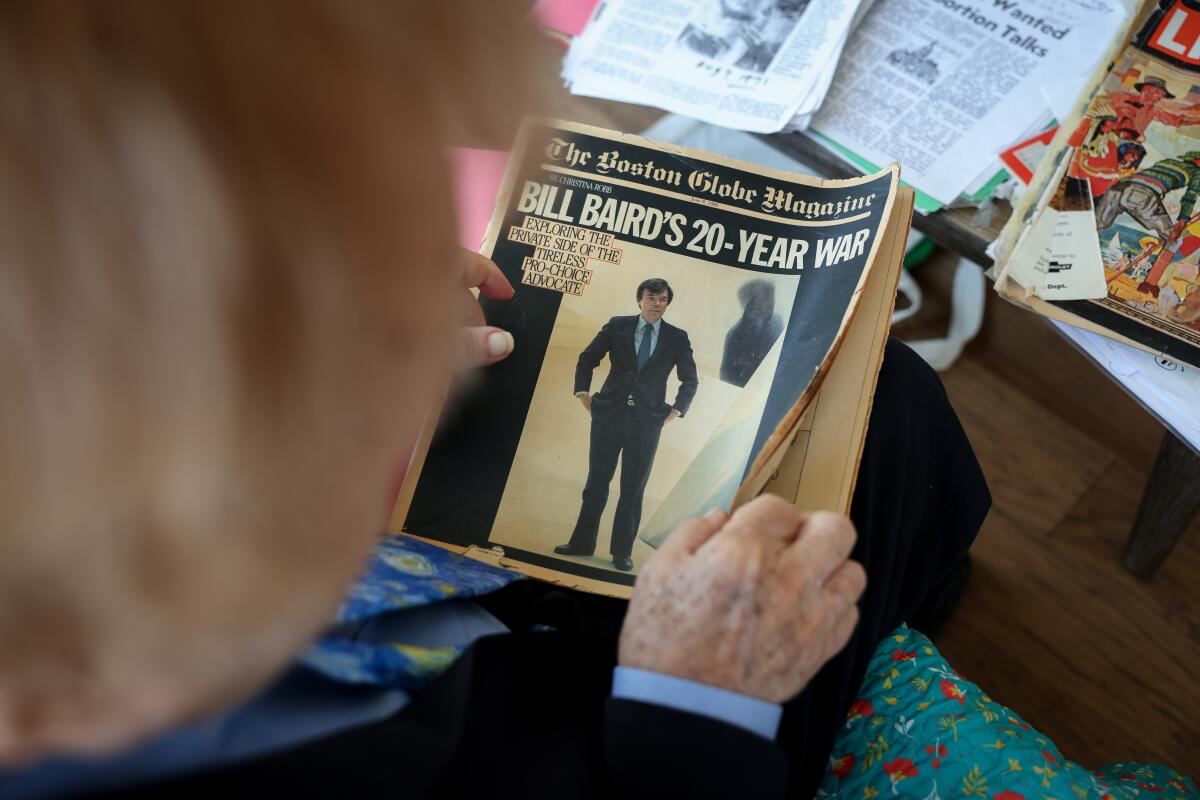

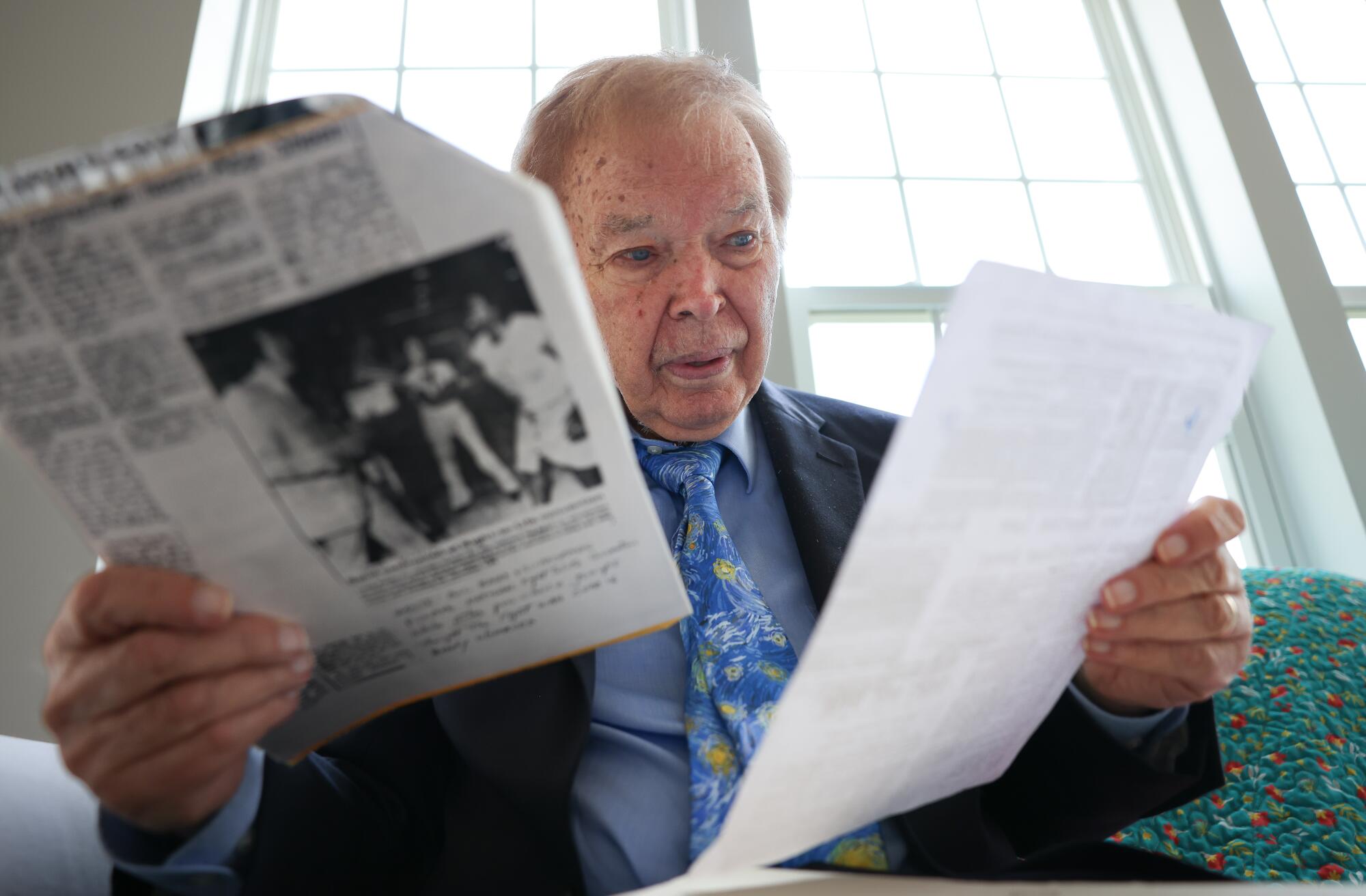

1

2

3

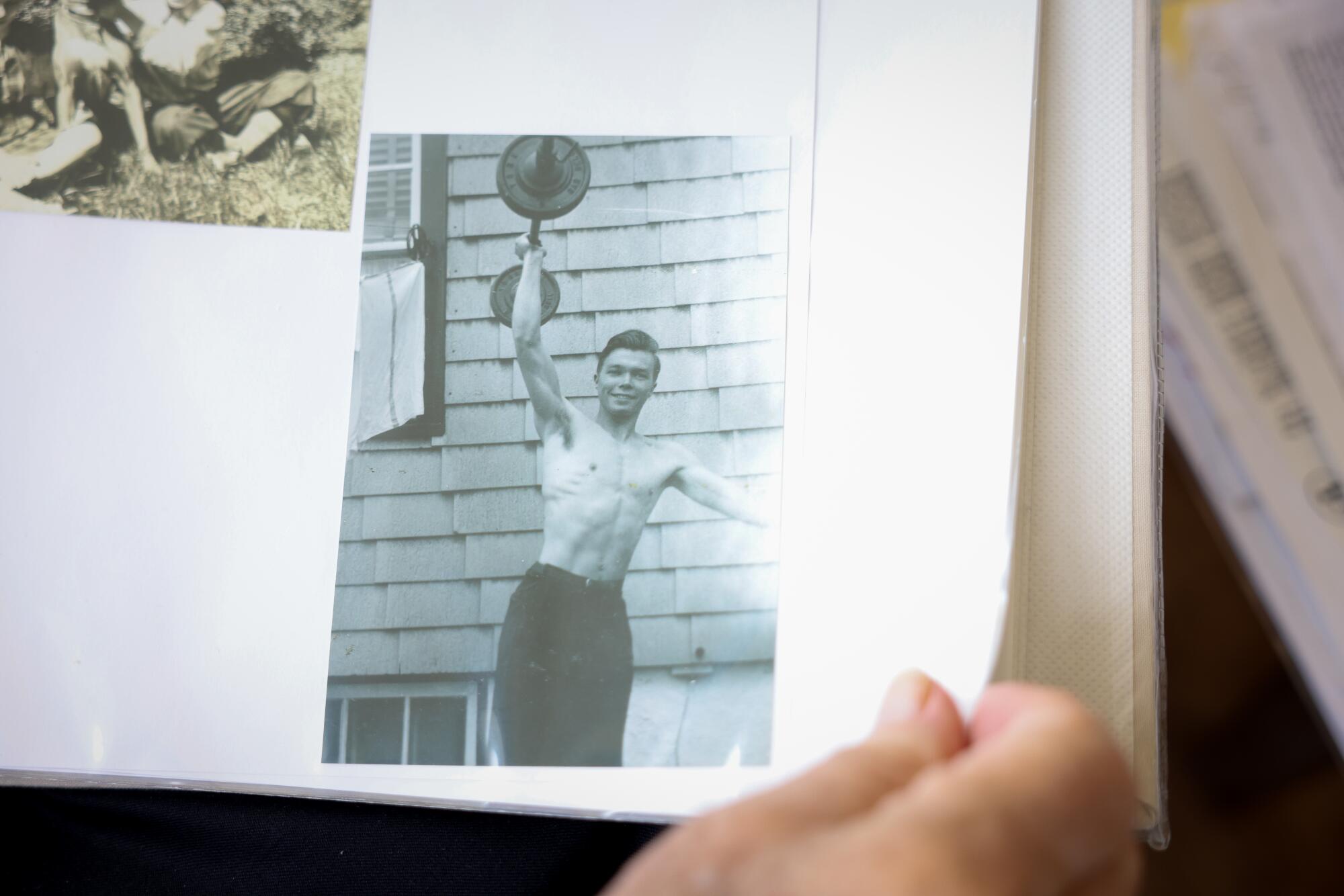

1. Baird looks at an article about him from 1985. 2. He holds a photograph of his mobile clinic, which he created in a 25-foot van and drove into communities to provide free health information and hand out free birth control. 3. Now 92, Baird won a 1972 Supreme Court decision that legalized contraception for unmarried women. (Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Baird’s crusade six decades ago for reproductive and abortion rights is at the center of today’s politics. But he sees himself as a misunderstood rebel relegated to a footnote in a history he helped create. “I went to jail for them,” he said, with a bitterness that hovered in the late morning light. “I did things many of them didn’t have the guts to do.”

He regards the battle to protect women’s rights as unfinished business. He tightens with anger when he reflects on the overturning of Roe vs. Wade in 2022 and the fact that Republican senators have refused to make access to contraception a federal right.

“I’m a street guy,” he said. “I’m no fancy Harvard lawyer. But I won Supreme Court cases. I had to take on so many forms to outwit the powers that be.” Back in the day, when someone tried to silence him or stop one of his protests, Baird, who can quote the Bible as accurately as he can the Constitution, would stare them down and say, “I’m gonna own your house.”

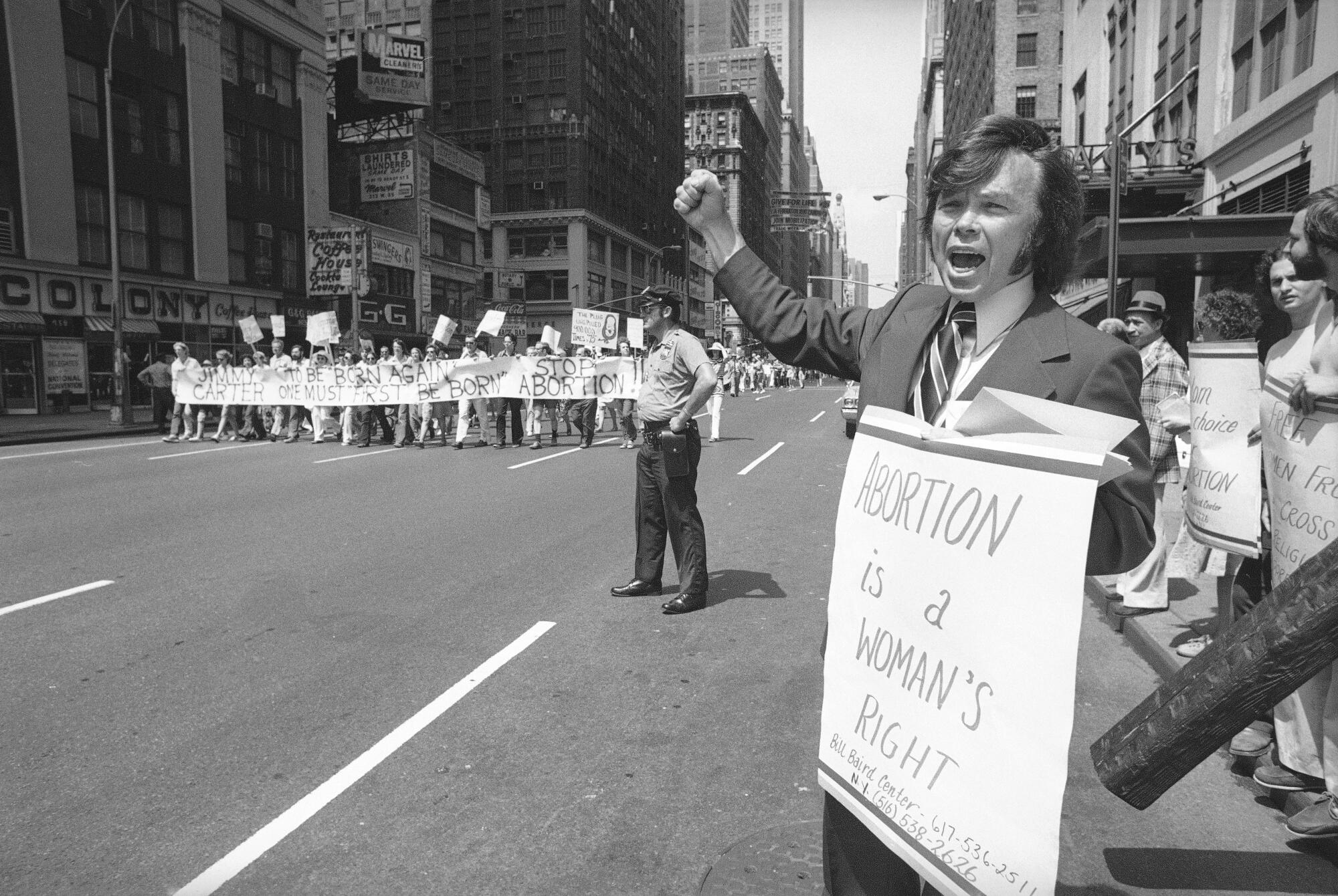

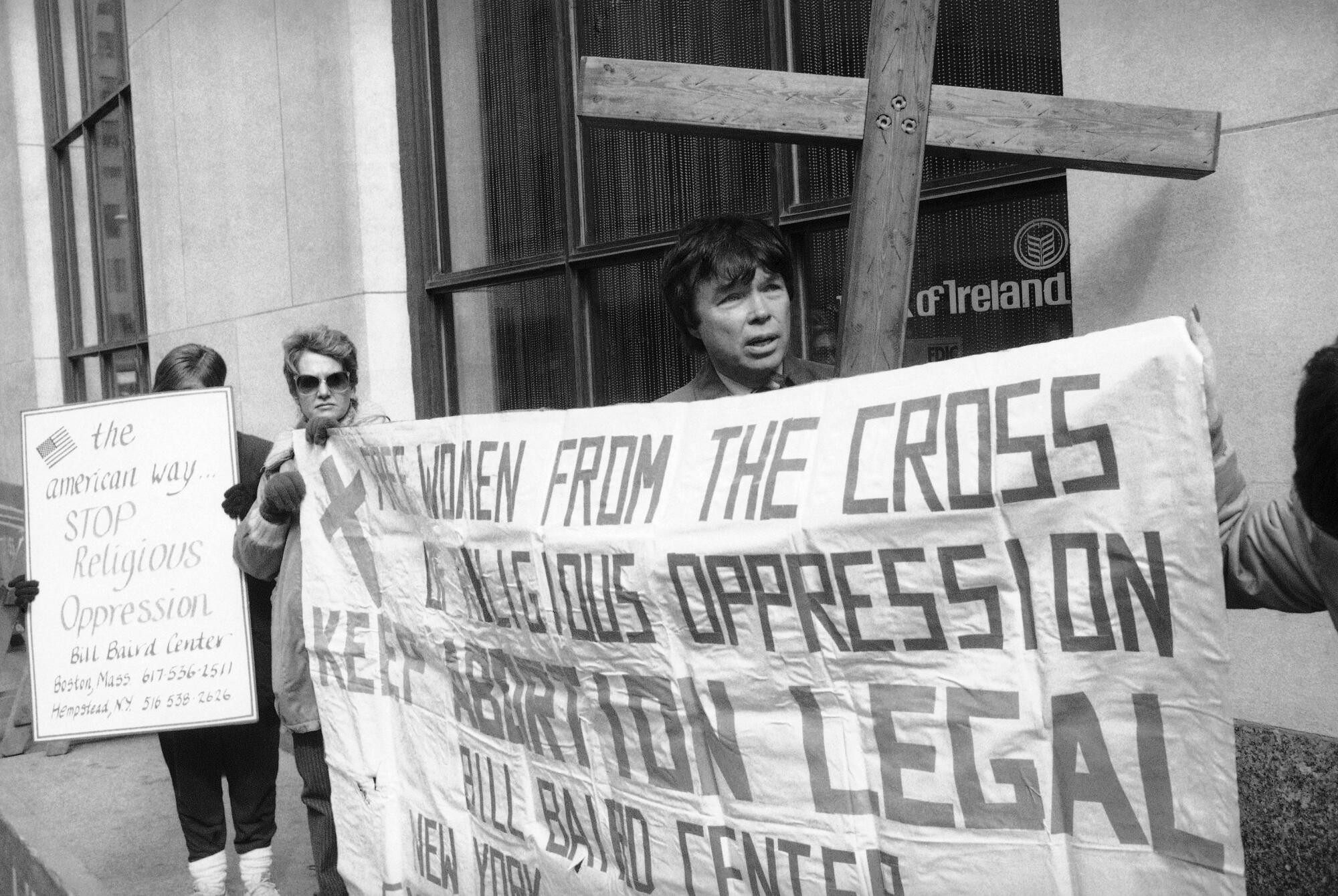

Baird was paging through newspaper clippings the other day, reliving a past when he wore sideburns and flared trousers and showed up in front of churches and town halls dragging a wooden cross and a sign that read: “Free women from the cross of religious oppression.” He remembered when Falwell called him “the devil” and when dozens of police officers appeared in Freehold, N.J., in 1966 to arrest him for handing out contraceptives.

Walking with a cane has slowed him, and at times — bent against the light, sprinklers clicking in the distance — it is clear what the years have taken. A slow lift of the arm, a patch of white whiskers the razor missed beneath the chin. “Can you read this line?” he asked. “My eyes aren’t so good anymore.” But his fervor remains as potent as his desire for respect; he is a man who on a workless morning greets you wearing a blue tie and a boxer’s fading grace.

His wife, Joni, a former preschool teacher, fact-checked his reminiscences and let him know when he repeated himself.

“You told him that yesterday,” she said.

“Yes, but there’s a purpose,” he said.

“Sometimes you forget.”

“That is true,” he said, “and I love you for it.”

He paused.

Baird’s pursuit of reproductive and abortion rights began in the early 1960s when virginity was spoken without irony and things related to sex came in unmarked brown paper bags. In some states, married women younger than 21 could not get contraceptives.

A graduate of Brooklyn College, Baird was hired as clinical director of Emko, which manufactured contraceptive foam. One day in 1963 while in Harlem Hospital, he saw a woman with a coat hanger embedded in her uterus. She was bleeding heavily, and he embraced her before she died. The moment was at once horrifying and revelatory. It became his origin story, repeated so often that it fell into a cadence, but never lost its hold on him.

“No one should die like that,” he said. “I wanted to educate the public. I wanted to prevent unwanted pregnancies that brought unwanted children. I grew up poor. I knew what that was like. It hurt poor women the worst.”

So, Baird became an itinerant voice in an era of civil rights protests and a burgeoning women’s movement.

He turned an old postal truck into the “Plan Van,” complete with a fake fireplace and chairs, that he drove to poor neighborhoods to educate women on birth control. He started clinics to counsel women and refer them to doctors for abortions that were illegal across much of the country. The Catholic Church despised him. Cops and critics grew accustomed to his publicity stunts, including a poster board displaying a skull and crossbones and his Penthouse magazine headline “Profiles in Courage: Bill Baird.” He was arrested eight times in five states.

He became famous with his 1967 arrest during a talk at Boston University before hundreds of coeds and a campus full of police who were there to uphold a nearly century-old state law against crimes of “chastity, morality and decency.” Baird, who has the timing of an actor and the brazenness of a raven, knew he would violate the statute when he offered contraceptives to women who rushed the stage. He told police it was hypocritical to arrest him given that a nearby department store, which was also ignoring the law, sold and collected taxes on the same contraceptives.

“I lived through that time,” Waxman said. “He was pretty damn brave to get up and give that lecture.”

A judge called him “a menace to the nation” and he was jailed for 36 days. He appealed to the Supreme Court, which two years earlier had ruled in Griswold vs. Connecticut — a case brought by Planned Parenthood — that married couples were entitled to contraceptives. There was no such protection for single people. Baird wanted to change that.

In November 1971, his lawyer argued the case before the Supreme Court, and five months later, Baird won in a 6-1 landmark decision that gave all adults access to contraception. Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote: “If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted government intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.”

Eisenstadt vs. Baird was a victory for women. But it highlighted the animosity between the feminist movement and Baird. Women’s groups cited the Griswold decision much more than Baird’s. A number of feminist leaders criticized him as a nuisance. He believed both sexes should work together for civil and privacy rights, but his brash style, including trying to burst into a women’s meeting he was barred from, unsettled some.

“Female supremacy is as evil,” he said, “as male supremacy.”

In 2000, Friedan said Baird “has been trying to muscle in, exploit, damage, divert, disrupt the women’s movement for 20-odd years.” A Boston Globe columnist wrote: “It’s uncanny. Even if you agree with everything he stands for and give him credit for all the good things he has done, still, there is something maddeningly off-putting about him.”

In the 2023 documentary on Baird, “Yours in Freedom, Bill Baird,” feminist activist Ti-Grace Atkinson said he had a “huge ego that reminded women of the worst things they had to deal with in their lives of men asserting rights over them.”

Joni Baird, who with Baird was co-director of the Pro Choice League, sees it differently: “When I think about the context of history,” she said, “women for centuries, and especially women in the ’60s, like my own mother, who became this ultra-feminist, had been oppressed. They looked at men as the enemy. Not all women, but a lot of the leaders did. They wanted to be the leader now. They wanted to take the ring. They invalidated Bill, and they continue to. He is a warrior. A lot of women in those days weren’t like that. They felt overwhelmed by him.”

Baird’s childhood was shaped by feelings of unworth. The son of immigrants — a hard-drinking father from Scotland and a reproving mother from Germany — Baird and his siblings grew up poor in Brooklyn, N.Y. “My mother used to tell me, ‘You’re stupid, you’re ugly.’ Not my brother Robert. He was handsome. Eddie was handsome. But I was ugly. She felt that way about me.”

He was a fast kid — “like a rabbit” — who haunted the railway station, peeling silver linings from Pall Mall cigarette wrappers to sell at the junkyard. Baird took in other people’s laundry, swept a synagogue and turned over trash cans to collect newspapers that he’d sell to recyclers for 75 cents for 100 pounds. His abusive father almost strangled him to death one night with a dog leash. Baird learned to protect himself and became a skilled fistfighter. Much later, he would say that Democrats and the women’s movement lacked the aggression needed to defeat the hardball tactics of the Christian right.

Baird was closest to his older sister Louise, who died of a cerebral embolism, gangrenous appendicitis and pneumonia appendicitis when she was 12 and he was 9. The loss shattered him and his mother, who one day when Baird returned from school was “singing ‘Ave Maria’ in a weird voice” and knitting a blanket for her dead daughter. Baird blamed his family’s poverty for not providing his sister with proper medical care.

“In those days,” he said, “they used to have a cart that drove the coffin around the neighborhood so people could say goodbye. I wept. I was so angry. I said, ‘She’s dead because we don’t have any money. That’s wrong.’ I said that if I ever get out of this poverty, I would do my best to go to college and become something and spend my life helping people.”

Louise and the dying woman at Harlem Hospital were woven into Baird’s activism — victims of poverty and religious piousness at the expense of basic human rights.

1

2

1. Baird at home with his wife, Joni. 2. A bottle of Emko contraceptive vaginal foam, one form of birth control that Baird provided in his mobile clinic. (Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

His work over the decades cost him much: Emko fired him for handing out free contraceptives. One of his three clinics was torched. Death threats against him forced him to move his first wife, Evelyn, and their children to another state. The couple divorced and he remains estranged from his children. Money has long been a problem. The speaking fees have mostly vanished; every now and then a student researching a paper on abortion calls him. The house he lives in was bought after Harvard University purchased his archives.

Time has spun forward for Bill Baird, but old torments persist. His home in Bucks County — about 40 miles north of Philadelphia — sits in one of the most politically contentious districts in a vital swing state. There have been battles over book bans, gender identity and women’s rights. He is bemused and alarmed that conservative politicians and the Christian right want to invoke the Comstock Act, an 1873 anti-obscenity law, as a way to limit reproductive rights.

The past is a little blurry, but mostly distinct. His mind and words can be as sharp as decades ago when he warned of “religious tyranny” and botched abortions.

In the 1960s, when Baird was known for providing contraceptives, he began receiving letters: “I am a mother. 15 children, 13 living. Age 42,” wrote one woman. “Doctor said I could have five more [children]. I don’t need anymore. I need your help please.” Another implored: “I am 19-years-old and I have three children and my fourth one is due in one month and after it is born I would like to use Emko [contraceptive foam] to keep from getting pregnant again.”

“Women came to me from all over the country,” Baird said. “Sometimes I gave out 2,000 contraceptive foams in a week.”

He added, “I knew I was part of history. Ninety-two years of my life have been spent fighting for civil rights. But it’s a difficult job because you’re so misunderstood. All I want to do is educate people and prevent unwanted pregnancies. I thought I’d get support from the public. Nothing. To this day, I’ve been scorned.”

But the kid from Brooklyn succeeded where many didn’t. He’s still at it. Sitting in the sunroom, a loaf of fresh bread on the counter, Baird, who once delighted in quoting Scripture to right-to-lifers, reached for another file of clippings. His hands were thick, his eyes squinting. But he seemed to have it all memorized; the victories, and the gnawing slights that drew a gentle reprimand from Joni: “One thing about you, Bill, you can’t let go of things. You’ve got to let go, Bill.”

He smiled at the impossibility of it.

He moved his cane to the side and left the file open on the table before him. He is smaller, more stooped, than in his younger days, but the slyness that defeated so many of his enemies remains intact. One can hear in the aged softness of his voice the choir boy he once was; the child who hid in the attic from his father; and the man who was accustomed to jail cells. He has survived beatings, a bullet, prostate cancer, colon cancer, appendicitis and COVID.

“He’s like Rasputin,” Joni said. “You can’t kill him.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.