Mass shootings in Mexico become an issue in the presidential race

SALVATIERRA, Mexico — They crashed the Christmas bash after midnight bearing assault rifles.

“The gunmen just went in and began shooting,” said Luis Almanza, whose son was among the revelers smashing a piñata and dancing to a live norteño band inside a former hacienda. “They wanted to kill everyone.”

Authorities later counted at least 195 shells expended in the Dec. 10 assault, which left 11 people dead, including Almanza’s son.

The attack was one of three high-profile massacres this month in Guanajuato state, an industrial and agricultural hub that in recent years has mutated into a battleground for organized crime. With the country preparing for national elections in June, it was not surprising that the violence quickly became politicized.

“This barbarism cannot continue,” Xóchitl Gálvez Ruiz, the leading opposition candidate for president, wrote on X, formerly Twitter. “An urgent change is needed to the security policy of the federal government.”

Taking aim at President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his strategy to fight crime with “hugs not bullets” by improving economic and educational opportunities, Gálvez continued: “Enough with hugs for the criminals and bullets for the young people.”

For many Mexicans, it was difficult to square the headlines with official statistics showing that homicides are on the decline.

There were 32,323 homicides in Mexico last year, down 9.7% from 2021, according to the government, which has reported that killings were on pace to fall another 9% this year. The total is about 50% higher than it was a decade ago.

A study published in Science estimated that Mexican cartels recruit about 360 workers each week to replace those lost to violence or incarceration.

The December massacres have put the president on the defensive even as polls suggest his favored candidate, Claudia Sheinbaum, will win the race to succeed him.

López Obrador has repeatedly refused to acknowledge that broad swaths of Mexico are under the control of criminal gangs. After the Christmas party massacre, he called multiple killings “the exception, not the rule.”

“A lot of people think things are getting better,” the president said.

A research group, Causa en Común, counted 427 massacres — defined as killings of three or more persons — in Mexico between January 2023 and mid-December. The total for 2022 was 500.

López Obrador also suggested that drug use was a factor in the Christmas party attack as well as in the case of five medical students and one of their friends who were found shot dead on Dec. 3 in the Guanajato city of Celaya.

Forensic tests showed that none had illicit drugs in their systems, according to state officials.

Fabiola Mateos, the mother of two of the students, publicly accused the president of having “re-victimized” the slain men.

The gruesome killing of Ariadna López shocked Mexico, spurred protests in the capital and highlighted the nation’s epidemic of violence against women.

The third Guanajato massacre took place Dec. 9 in the city of Salamanca, where assassins on motorcycles opened fire on a barber shop, killing four men.

Police have publicly announced only one arrest in the three cases, the slayings of the medical students. Nationwide, more than 90% of homicides go unsolved.

Many of the victims of the recent violence “belong to a generation that has spent all of their lives in the middle of a lost war,” wrote columnist Salvador Camarena in the El Financiero newspaper, referring to a battle against drug cartels that began in 2006 and is widely blamed for sparking a massive rise in homicides. “All they have heard about are cartels, massacres, police, soldiers, kidnappings...”

Polls have shown that insecurity is the major worry of Mexican voters before next year’s elections, which include balloting for a new president.

Homicides soar as two gangs battle it out in the Mexican state of Guanajuato.

Perhaps nowhere is that more true than in the state of Guanajuato, which once stood out as an island of relative calm. General Motors, Mazda and Toyota make autos here, and U.S. tourists and retirees flock to the leafy enclave of San Miguel de Allende.

Now the state has the fourth-highest homicide rate in the country, with a total of 4,256 killings last year, or 68 for every 100,000 residents. Though that figure is down 20% from 2020, it is well over double the national rate and nearly seven times the rate for Los Angeles.

Across Guanajato, a local crime syndicate known as the Santa Rosa de Lima cartel has been engaged in a bloody turf war with the much larger Jalisco New Generation cartel.

The rivals battle for control of contraband gasoline, local methamphetamine markets and dominion over drug-smuggling routes leading north to the United States.

The city of Salvatierra, population 90,000, is designated as one of Mexico’s pueblos mágicos because of its heritage of colonial structures. But an aura of tranquility masks a violent reality.

In 2020, people looking for their disappeared loved ones discovered a series of clandestine graves in Salvatierra that held the remains of 80 victims. Other killings are much more public, often carried out by hit-men on motorcycles.

“We are alone here,” said Rocío Alemán, 56, a shopkeeper. “The authorities never resolve anything and don’t provide us with security.”

“Here we have no peace, no tranquility,” she said. “I’d prefer that my two sons get out of here if they could.”

As crime engulfs many Mexican states, immigrants who’ve saved to retire there are reevaluating ties to home — and whether returning is worth the risk.

The ill-fated Christmas party, known as a posada, was organized by a group of young people, many of whom had known one another for years.

There were no publicly known threats to the party-goers, said Almanza, whose son Galileo, 25, managed the family’s vehicle smog-check business in town and had a 7-year-old son of his own.

At some point in the evening, according to official accounts, a group of uninvited guests arrived at the party. They were told to leave. Later, the ejected group returned, accompanied by about a dozen heavily armed men.

The shooting did not appear to have been aimed at anyone in particular, according to witness and police accounts. The assailants soon drove off, shooting up cars and motorbikes parked outside the hacienda.

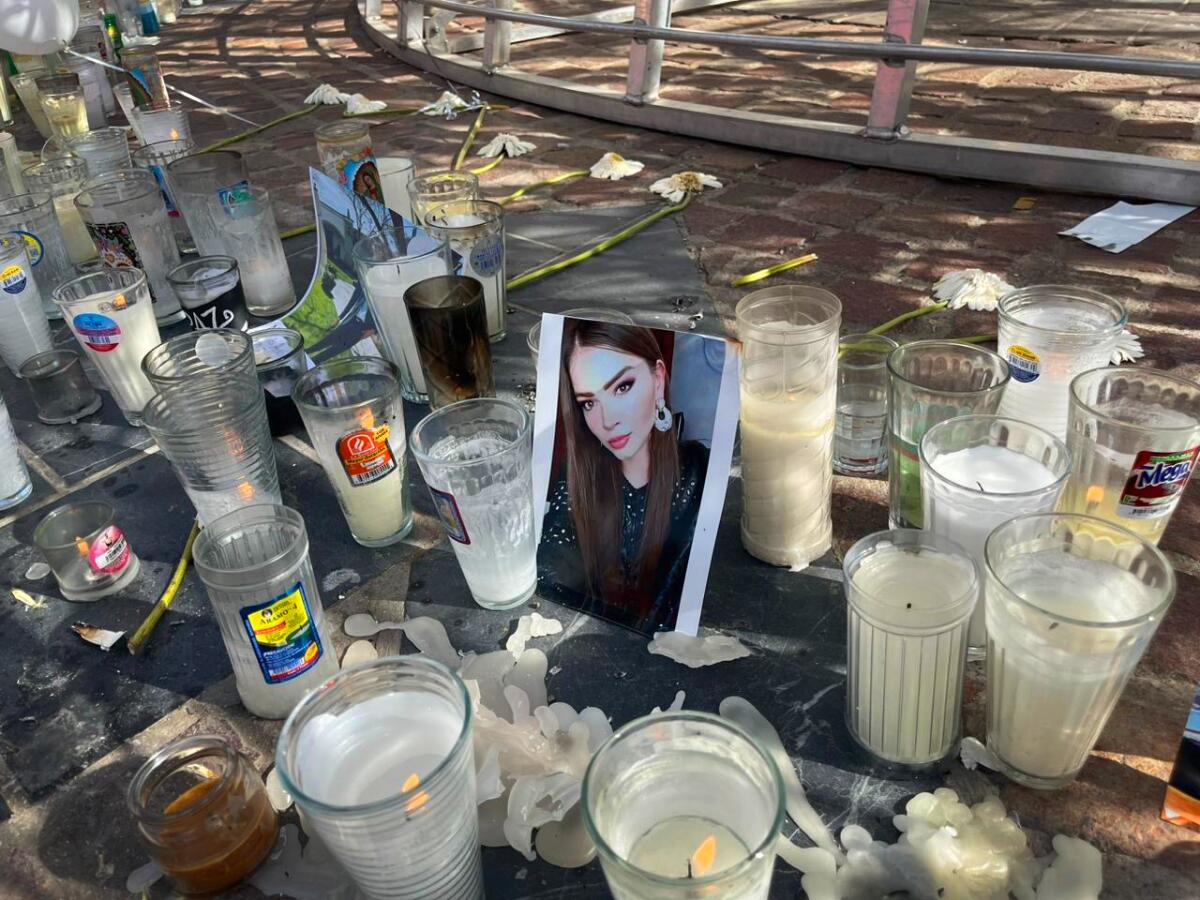

Galileo Almanza died at the scene. Also killed was Thalía Cornejo, 25, a former area beauty queen who was studying psychology in college and was home for the holidays. Dinastía Cornejo, the band playing at the time of the attack, lost one member.

“There’s not a safe street here now,” said Luis Almanza, 57. “There are killings on the street, killings on the corner, killings in front of my house. Everyone is scared.”

For days after the slayings, funeral processions filled the narrow streets of Salvatierra. Hundreds marched to demand justice. The lights of the town Christmas tree were turned off, replaced by flickering candles on the ground to honor the dead.

On the tree, relatives placed a print with a likeness of some of the victims embracing. Above the image were the words: “Salvatierra: One day we will shine anew.”

McDonnell is a staff writer and Sánchez Vidal a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.