Hurricane Otis stuns Mexico, slamming Acapulco with ‘brutal’ Category 5 strength and cutting off contact

MEXICO CITY — A Category 5 hurricane, the most powerful on record to hit Mexico’s Pacific coast, slammed into Acapulco early Wednesday, leaving the resort city without power and cut off from road and air access amid devastation that officials were only beginning to assess.

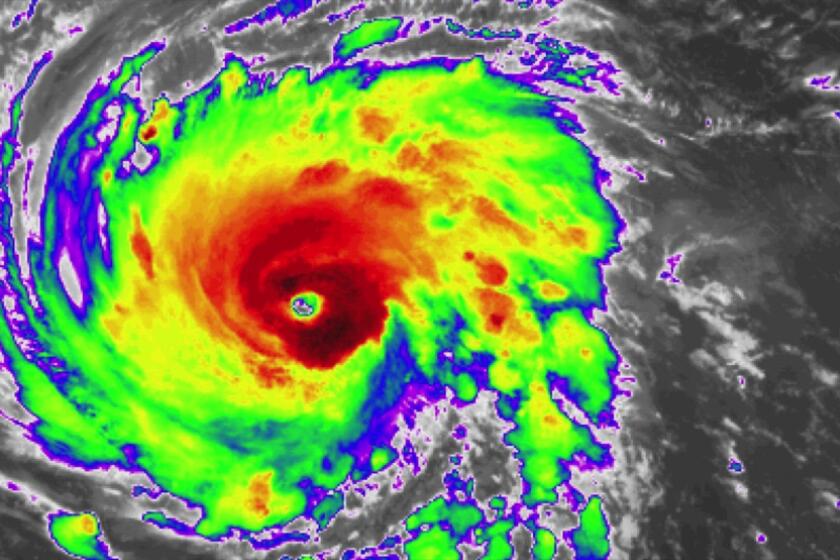

The fast-moving Hurricane Otis made landfall near Acapulco at 12:25 a.m. and tore through the coastal zone with torrential rains and 165 mph winds, shaking structures and tearing roofs off buildings.

There was no immediate word on casualties or an official accounting of the damage as contact with the area was “completely lost,” a grave President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said at a morning news conference in Mexico City, 235 miles to the northeast of Acapulco.

Relief crews and military aid units were trying to reach Acapulco and smaller towns in Guerrero state, but landslides and debris blocked major highways, airports were shuttered and rivers were raging over their banks.

The National Hurricane Center had warned of a “nightmare scenario” as Otis bore down on Acapulco, which is home to almost 1 million permanent residents. Many inhabitants reside in precarious cliff-side communities vulnerable to landslides during downpours. Hillside neighborhoods and towns outside Acapulco were also vulnerable.

Otis, fueled by warm offshore waters, rapidly escalated into a Category 5 hurricane, giving authorities and residents relatively little time to brace for its impact.

Experts said the storm’s surprisingly swift transformation from tropical storm into the most powerful class of hurricane may be another indication of how global warming is shifting weather patterns.

Should Cape Coral and other low-lying cities in Florida rebuild in an era of more intense hurricanes, higher rainfall and rising seas?

Images circulating on news sites and social media showed vast destruction throughout Acapulco and elsewhere in Guerrero state. Terrified residents and visitors sheltered in homes and hotel rooms as windows shattered, pieces of buildings flew in the air and the city’s signature palm trees bowed in the ferocious winds.

Luisa Peña hid in a closet in her hotel room in Acapulco as the ceiling collapsed, the windows blew out and the floors flooded.

“I began to pray, to meditate, to try and calm myself although the panic was so great that the only thing I asked for was one more chance,” a visibly shaken Peña, her hair blowing wildly, said in a widely circulated video on social media.

Sandra Romandía Vega, a journalist who was taking refuge in a shelter, wrote on X, formerly Twitter, of the “brutal” clamor as Otis enveloped Acapulco. “A roar, a fury that made things fly, chairs, umbrellas, trees, and the echo of devastation.”

As crime engulfs many Mexican states, immigrants who’ve saved to retire there are reevaluating ties to home — and whether returning is worth the risk.

After the storm moved inland, diminishing to below tropical storm strength but still unleashing heavy rain, images of mayhem emerged from Acapulco. Dazed residents picked their way through streets littered with debris as emergency vehicle lights flashed.

Video of the typically bustling downtown hotel zone showed flattened palm trees, condo towers with their facades sheared off and mangled seaside restaurants. Roads were blocked by battered cars and heaps of twisted metal.

The level of destruction in some of the city’s most upscale districts raised concerns about the fate of those in poorer areas, where many reside in simple hillside homes made of cinder block and tin.

Mexico’s state electricity provider said the storm knocked out power to more than half a million users. By midday, it said it had restored power to about 40% of them.

López Obrador was en route to the region, accompanied by his defense and naval chiefs in vehicles along the heavily damaged highway. The Mexican president said Otis was stronger than Pauline, the Category 4 hurricane that hit the country’s Pacific coast in 1997, killing hundreds and destroying or damaging thousands of homes.

Alarmed about the fate of loved ones in Acapulco, people began posting pictures on social media of relatives and others with whom they had lost contact — asking if anyone knew their whereabouts — as the tortuous communication blackout dragged on.

“There have only been drops of information,” Sen. Manuel Añorve, a federal senator representing Guerrero state who was in Mexico City when the storm hit, told the Diario 24 Horas news outlet. “I haven’t been able to contact my colleagues in Guerrero, I haven’t been able to reach my wife, my children, my mother, my siblings, my friends. ... I’m very worried.”

Daniel Negrete, 33, hasn’t heard from his mother, Adriana Esqueda, 64, since the hurricane struck.

She left Mexico City with three relatives on Tuesday to spend six days lounging at the Torre Blanca condominium in Acapulco. As the rain and wind intensified in the early evening, Esqueda called her son and told him that they would shelter in the apartment. A few hours later, she called again to say the weather had gotten worse, and he suggested that they stay far from the apartment’s windows.

“She said yes, not to worry and that she’d let me know in the case of anything,” Negrete said.

Their last conversation was just before midnight. He hasn’t been able to reach her by phone or text. Negrete, who lives in Mexico City, spent Wednesday posting messages on social media asking people to contact him if they had information about the condo. He wanted to go find her but backtracked after learning about the road damage.

A study published in Science estimated that Mexican cartels recruit about 360 workers each week to replace those lost to violence or incarceration.

“All the time you’re thinking, what happened, is your family OK, especially my mother, and waiting for news.”

Karla Altamira, 40, said she had not heard from her brother, Carlos, 35, since just before the storm hit.

Soldiers and razor-sharp metal at the Mexico-Texas border don’t deter migrants who traveled months to get there, as numbers of those fleeing to the U.S. soar.

Carlos, a Mexico City resident, was in Acapulco for an international mining conference and staying at a Holiday Inn on the beach. In one of his last voice messages to his family before he lost service, he said his hotel room no longer felt safe, and that hotel administrators had ushered him and other guests into a basement area.

“We have no idea what’s going on,” Karla said. “It’s very frightening.”

But she said she didn’t blame authorities for a lack of preparation. “Nobody knew it would be so strong,” she said. “We were all caught off guard.”

A day before Otis struck, the storm had been forecast to grow from a tropical storm into a Category 1 hurricane before hitting land. But it gained wind speeds of 115 mph in just 24 hours, said experts, calling it one of the fastest such accelerations on record.

Climate experts said more analysis was necessary to explain exactly how and why the hurricane intensified so quickly, but many agreed that El Niño and human-driven climate change are probably both to blame.

“I would expect that all these factors contributed,” said Suzana Camargo, a professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Floods, fires, extreme heat, awful air quality, warming seas: As extreme weather engulfs the nation, the United States resembles a disaster movie set.

El Niño, a naturally occurring climate pattern driven by shifts in winds and currents in the Pacific, is active this year, and often leads to more hurricane activity in the region, she said.

But the burning of oil, coal and gas, which expel heat-trapping carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere, also probably played a role, she added. Most of that extra heat has been absorbed into the ocean — and warmer waters as well as warmer air add potency to tropical storms.

“It is making them stronger,” Camargo said.

A recent study published in the journal Scientific Reports found that Atlantic Ocean hurricanes were now more than twice as likely to strengthen from a Category 1 into a Category 3 hurricane during a 24-hour period than during the 1970s and 1980s.

Wildfires in Canada and Hawaii. Hurricane Hilary set to strike California. Scientists have warned about worse storms and more frequent fires for years.

“While it would take specific research and additional analyses to tie Hurricane Otis directly to climate change, we do know that warmer ocean temperatures can support the strengthening of a storm like Otis,” said Andra Garner, an author of the recent study and an assistant professor at Rowan University in New Jersey.

“A warmer climate really stacks the deck against us, if you want to think of it that way,” Garner added. “It makes it more likely and more possible for storms like Otis to occur.”

Times special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in Mexico City, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.