Border Patrol failed to review girl’s medical file before she died in custody, report says

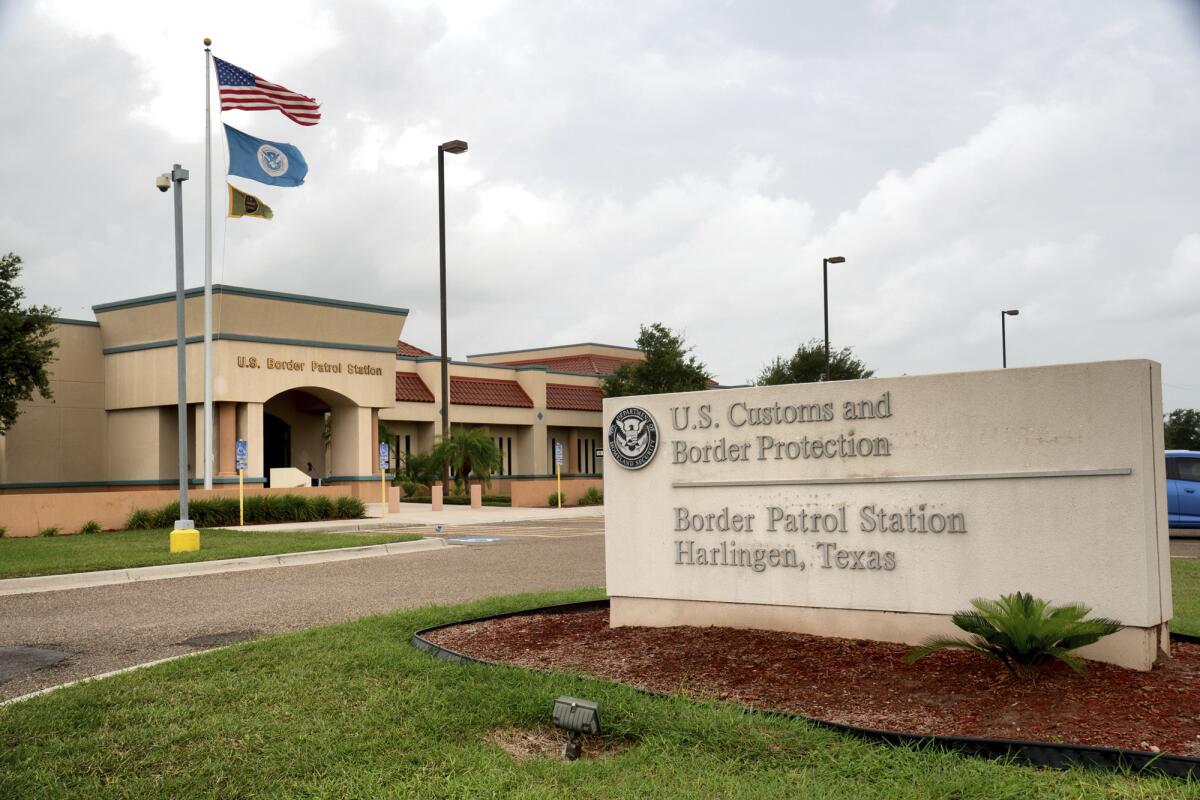

HARLINGEN, Texas — Border Patrol medical staff declined to review the file of an 8-year-old girl with a chronic heart condition and rare blood disorder before she appeared to have a seizure and died on her ninth day in custody, an internal investigation has found.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has said the child’s parents shared her medical history with authorities May 10, a day after the family was taken into custody.

But a nurse practitioner declined to review documents about the girl the day she died, the agency’s Office of Professional Responsibility said in its initial statement Thursday on the May 17 death. The nurse practitioner reported denying three or four requests from the girl’s mother for an ambulance.

Anadith Tanay Reyes Alvarez, whose parents are Honduran, was born in Panama with congenital heart disease. She received surgery three years ago that her mother, Mabel Alvarez Benedicks, characterized as successful during a May 19 interview with the Associated Press.

A day before she died, Anadith showed a fever of 104.9 degrees, the Customs and Border Protection report said.

A surveillance video system at the Harlingen, Texas, station was out of service since April 13, a violation of federal law that prevented evidence collection, according to the Office of Professional Responsibility, which is akin to a police department’s office of internal affairs. The system was flagged for repair but wasn’t fixed until May 23, six days after the girl died.

Humanitarian volunteers confronted two Border Patrol agents at the end of a trail and filmed the conversation.

The investigation relied on interviews with Border Patrol agents and contracted medical personnel, and raises a host of new troubling questions about what went wrong during the girl’s nine days in custody, which far exceeded the agency’s own limit of 72 hours.

Investigators gave no explanation for decisions that medical staff made and appeared to be at a loss for words.

“Despite the girl’s condition, her mother’s concerns, and the series of treatments required to manage her condition, contracted medical personnel did not transfer her to a hospital for higher-level care,” the Office of Professional Responsibility said.

Troy Miller, the Customs and Border Protection acting commissioner, said the initial investigation “provides important new information on this tragic death,” and he reaffirmed recent measures, including a review of all “medically fragile” cases in custody, to ensure that such detainees are released as soon as possible. The average time in custody has dropped by more than half for families in two weeks, he said.

Following the expiration of Title 42, U.S.-bound migrants are still arriving at Mexico’s southern border to travel north, in a chaotic scene.

Anadith’s death “was a deeply upsetting and unacceptable tragedy. We can — and we will — do better to ensure this never happens again,” Miller said.

Anadith entered Brownsville, Texas, with her parents and two older siblings May 9 when daily illegal crossings topped 10,000, as migrants rushed to beat the end of a pandemic-related policy on seeking asylum.

She was diagnosed with the flu May 14 at a temporary holding facility in Donna, Texas, and was moved with her family to Harlingen. The staff had about nine encounters with Anadith and her mother over the next four days at the Harlingen station over concerns including high fever, flu symptoms, nausea and breathing difficulties.

She was given medications, a cold pack and a cold shower, according to the Office of Professional Responsibility.

A court-appointed monitor expressed concern in January about information on chronic conditions of medically fragile children not getting through to Border Patrol staff.

The Biden administration was worried border crossings would surge after Title 42 expired. Officials, experts and migrants help explain why numbers have fallen instead.

Dr. Paul H. Wise, a Stanford University pediatrics professor who was in south Texas last week to look into the circumstances of what he said was a “preventable” death, said there should be little hesitation about sending ill children to the hospital, especially those with chronic conditions.

Anadith’s mother told the AP that she informed the staff of her child’s conditions, which included sickle-cell anemia, and repeatedly asked for medical assistance and an ambulance to take her daughter to a hospital, but the requests were denied until the child fell unconscious.

Karla Marisol Vargas, an attorney for the Texas Civil Rights Project who is representing the family, said Border Patrol agents rejected her pleas for medicine until the day she died.

“They refused to review documents showing the illnesses that her daughter had,” Vargas said.

The family is living with relatives in New York while funeral arrangements are made.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.